Christmas: What it means and how it began-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

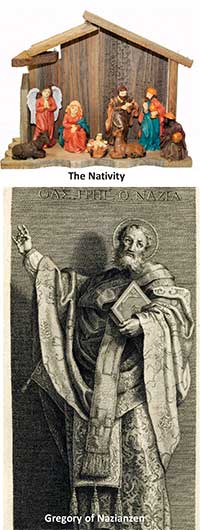

Celebrated by over two billion people across the world, Christmas commemorates the birth of Jesus Christ, a fact reflected even in translation: Naththal in Sinhala and Kristumas in Tamil. While most of its symbols were later cultural borrowings, its essence survives through the life story of Christ as related in the New Testament, in particular the four Gospels, two of which directly refer to Christ’s birth or Nativity: Matthew and Luke. The exact biographical details come to us from second-hand accounts, as with other religious leaders from that period, but what all these narratives tell us is the story of a poor carpenter’s son, preaching salvation and earning the ire and retribution of the government of Roman Judea.

We do not know whether December 25 was the actual date of the Nativity or whether it was a date chosen by the first Church fathers. The early Church taught, prophesied, and awaited the Second Coming of Christ (Acts 1:11 — “this same Jesus, which is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come in like manner as ye have seen him go into heaven”).

Scholars have conjectured that the need for a chronology charting the annunciation, nativity, crucifixion, and resurrection first cropped up when the early Church fathers felt the need to combat paganism and could no longer resort to the Second Coming as their justifying prophecy. One way of achieving this was by Christianising pagan rituals. The early fathers approved of this tactic: St Justin said that a noble thought, “wherever it comes from, is the property of Christians”, while St Ambrose declared that “all truth, whoever its interpreter may be, comes from the Holy Spirit.” On the other hand, Quintus Tertullian, a 2nd century Church leader, frankly wondered, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?”

When Christianity expanded from Bethlehem, Nazareth, and Jerusalem to the far corners of the Roman Empire, it embraced these rituals. The process was doubtless slow, and yet by the 4th century AD missionaries had converted vast swathes of the Empire, meeting success or martyrdom depending on where they were and who held power.

They operated on the twofold division of the Empire: between the Greek, the eastern side of the Mediterranean, and the Latin, the western side of the Mediterranean. From this division was born the rift between the Orthodox and the Catholic (and Protestant) church. It was the eastern side which first celebrated the coming of Christ, but they did so on a different date, January 6, and called it Epiphany or “manifestation.” The first commentaries on Epiphany come to us in the 2nd and 3rd century AD from a Church father, Clement of Alexandria, and as with much of the Roman Empire, the date seems to have been selected to compete with the Egyptian winter solstice. However, this theory has been critiqued.

On the Western side the evolution of Nativity took a different turn. The first written account demarcating December 25 as the day of Christ’s birth comes from the 4th century AD. Back then it was called the Feast of the Nativity. The main focus, historians tell us, was to combat various pagan cults and rituals celebrated by the Romans.

Three rituals took place between November and January: Saturnalia on December 17, Kalends (the first day of the Roman New Year) on January 1, and between them, the winter solstice, which in the reign of Emperor Aurelian (270–275 AD) was renamed “Sol Invictus” or the Festival of the Unconquered Sun and celebrated on December 25. That this was the ritual the Church fathers combated can be confirmed by the Chronograph of 354, a collection of Roman dates in which the entry for December 25 reads “Natalis Invicti Circenses Missus.” While this view has been contested, there is no doubt that the choice of December had to do with the popularity of pagan rituals among commoners and even the nobility.

The spirit of Nativity and all that it symbolised was eventually assimilated to this date. It’s a sign of how gradual and slow the process of converting people to the new religion was that in the early years, Church fathers from both sides of the Empire would complain of how locals worshipped the sun deity (the “Sol” of Sol Invictus) and only later attended the church. Leo I or Leo the Great, among the most important early Roman pontiffs, wrote of how “full of grief and vexation” he was at seeing followers bowing to the rising sun before entering the Basilica (a practice he condemned as an “old superstition”), while Gregory of Nazianzen, Archbishop of Constantinople (on the Greek side), urged that Christmas be celebrated “after an heavenly and not after an earthly manner”, drawing a distinction between the spiritual and the material and cautioning against “feasting to excess, dancing, and crowning the doors” — all hallmarks of festivals celebrated in the Empire. East and West met later on when the period between December 25 and January 6 was held as sacred by the Council of Tours in 567 AD; today this is known as the Twelve Days of Christmas.

To be sure, other days had been proposed earlier. Clement of Alexandria favoured November 18, Hippolytus of Rome thought that Christ was born on a Wednesday, and a document titled De Paschæ Computes written in 243 AD placed the date of his birth on March 28, “four days after God created the world.” By the time of the Norman conquest of 1066 AD, not only the date but also the name of the festival had been finalised: the word “Christmas” enters the lexicon as Crīstesmæsse in 1038 AD, and by the 13th century it had spread through the rest of Europe, where priests encountered and converted the pagan. If in Rome the fathers had to face Sol Invictus, in Germany further north they had to face Yule, which began with the winter solstice five days after the Saturnalia on December 22. From that emerged the festival we know as Yuletide, the main symbol of which, of course, is the Yule log.

Much of the history and evolution of Christmas to what it has become today, therefore, has to do with a tussle and later amalgamation between the spiritual and the ritualistic. On one hand, we have Christmas carols, which evolved from medieval hymns; on the other hand, we have Christmas cards, the first of which would be printed in 1843. In fact the 19th century is crucial, since much of what counts for symbols in Christmas emerged from the womb of Victorian England: a period in which, as the historian Robert Tombs has observed, people “believed in God” but “also in Progress, and commonly linked the two beliefs.”

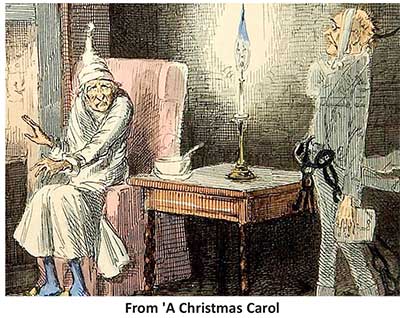

At a time when industrialisation swept through Britain (along with Western Europe) at a rate unprecedented in history, the secular aspects of Christmas triumphed over the spiritual, which caused something of a backlash; you see that backlash in certain popular works of art from that time; particularly the novels of Charles Dickens, who immortalised Christmas in A Christmas Carol (although curiously and incongruously enough that story makes no mention of that most beloved embodiment of the season, Santa Claus).

Santa Claus, even carols and trees, not to mention cards and lights, clearly show that while a division did exist between the spiritual and the material, the separation was not always that clear-cut. For instance, Santa Claus’s “ancestor” was Saint Nicholas, Bishop of Myra (modern day Turkey), who performed many miracles, was forgotten after his passing away and revived as the centre of a cult in Slavic countries such as Russia and the Ukraine, migrating from the East to the West across the Atlantic through the historical fiction of Washington Irving and the illustrations of Haddon Sundblom, whose drawing of a jolly, bearded, old, red suited, ho-ho-hoing man in 1931 entered the popular culture. The illustration had been for a Coca-Cola ad, and it seems to have stuck on with the popular consciousness thereafter.

Thus the division between what was spiritual and what was not eroded, so much so that nothing separates the two; Christmas trees, to give another example, originated in Germany, yet it was also in Germany that, in the 19th century, the first “commercial” Christmas trees were decorated and planted. Carols, to give still another example, were preceded by hymns in medieval Europe, but even after they were popularised it wouldn’t be until 1833 that William Sandy would publish Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern. Other examples, multiplied a hundred or so times over, would serve to underscore exactly how Dickens’s “Christmas past” and “Christmas present” came together: not unlike how Buddhist philosophy absorbed local culture, leading to the “glamourisation” of Vesak in modern times.

Today, of course, calls are being made for Christmas to turn into more than just a festive season, in which charity, goodwill, and forgiveness triumph over greed and consumerism. In a period that witnessed an act of abominable, unforgivable violence against an otherwise peaceful community in Sri Lanka, our sincerest wish would then be that these values not only triumph, but that Christ’s message of peace and amity, preached more than a thousand years ago, prevents a return to violence and fanaticism.