Lethal and skiddy Malcolm Marshall or hostile gladiator Dennis Lillee: who is the greatest fast bowler?:by Mike Atherton

Source:thetimes

In the latest in our series discussing the best in sport, Mike Atherton and Simon Wilde debate two of cricket’s greats

Made of granite, black, upright and proud — in death as in life. In the small Anglican church of St Bartholomew’s, close to the south coast and therefore the breeziest and best beaches of Barbados, lies the gravestone of arguably the greatest all-round fast bowler of them all. The inscription reads: “Although our hearts are broken, we remember with a smile.” A generation of batsmen would smile ruefully at that.

Mourned across the cricketing world, Malcolm Denzil Marshall was only 41 when he died of colon cancer in 1999. The late 1970s to early 1990s, which represented the span of his career, was a time when even the greatest players made second, sometimes third homes in domestic competitions, as Marshall did with Hampshire and Natal, and so even former adversaries in international cricket could become close and valued friends. The large and eclectic turnout at his funeral was testament to that.

My choices of first pick batsman (Viv Richards) and fast bowler, Marshall, for any composite all-time world XI reflect some bias on my part, as personal selections in these non-definitive arguments always do. That West Indies team, helmed by Richards with the bat and Marshall with the ball, were the team of my youth, an incomparable collection of great and charismatic cricketers. The memory can deceive, of course, although mine is buttressed by having played against them, too.

My fifth County Championship match for Lancashire, in August 1987, was against Marshall at the old county ground in Southampton. The tremor that went through the Lancashire dressing room before that game was typical of a time when almost every county team had an overseas fast bowler, although it was heightened for Marshall, who was not far off his peak then: still very fast, skiddy, skilful and just mean enough, especially if riled.

We had our own West Indian tearaway in that game, Patrick Patterson, and there wasn’t much between them in pace. There would have been quicker bowlers before Marshall, although not by much I fancy, and I faced quicker later on — Allan Donald and Shoiab Akhtar, the quickest. There have been bowlers who swung the new ball more — Jimmy Anderson, Fred Trueman, say — as well as the old, as generation after generation of Pakistan bowlers have done. But as a package, combining all those qualities and more? Marshall was hard to beat.

Before sports science and professionalism levelled the playing field, the beaches and sunshine of the Caribbean imparted a natural early advantage, one then amplified by the hard work and discipline — not always appreciated — that characterised those West Indies teams under Clive Lloyd and Richards. Before Ian Bishop, very few bowlers from the region suffered serious back injuries, and that enabled them to handle the rigours of pre-central contract days better, when bowlers played as frequently for their domestic teams as they did for their countries.

It is remarkable to think that Marshall played the amount of cricket he did, bowling at the pace he did, for so long. To give an idea of his stamina and capacity for work, an essential first for a great fast bowler, consider this: Anderson, still playing 18 years after his first-class debut, has bowled 49,907 balls in first-class cricket. Marshall bowled half as many again, 74,654 balls all told for West Indies, Barbados, Hampshire and Natal. And, as county batsmen would tell you, he was a trier, whenever and wherever he played. He rarely went through the motions.

That range of experience made him the complete package. He was a quick learner, having played a solitary first-class game for Barbados before he was picked to tour to India. Playing county cricket especially, as so many of that generation of West Indians did, meant he learnt to cut down his pace when necessary so that he could move the ball this way and that, in the air or off the pitch. Despite his open-chested action, he initially found it easier to move the ball away from the right-hander, but developed an in-swinger soon enough.

In the Caribbean, though, with little movement in the air or off the pitch, he came sprinting in, arms and legs pumping, approaching the crease on a slight curve, holding the ball out in front of his chest to give the batsman a sighter before it became a blur. Then, he was only interested in pace rather than movement. What made him doubly dangerous in this mood was his height, or lack of it. Standing 5ft 10in only meant his bouncers were skiddy and hard to evade. He hit and hurt a lot of batsmen.

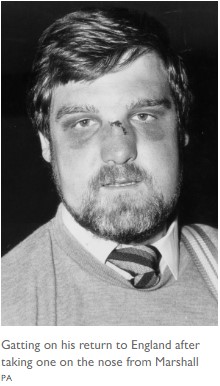

This was a time when there was no limit on the number of bouncers a bowler could bowl, unless an umpire stepped in, and Marshall and his comrades were not shy in using them. He sometimes came around the wicket to right-handers, to fire balls into the blind spot around the rib cage, although it was from over the wicket that he sent a searing bouncer crashing into Mike Gatting’s nose on England’s tour to the Caribbean in 1986, one of the more graphic illustrations of a fast bowler’s threat. The fielders had to pick pieces of Gatting’s nose cartilage from the ball.

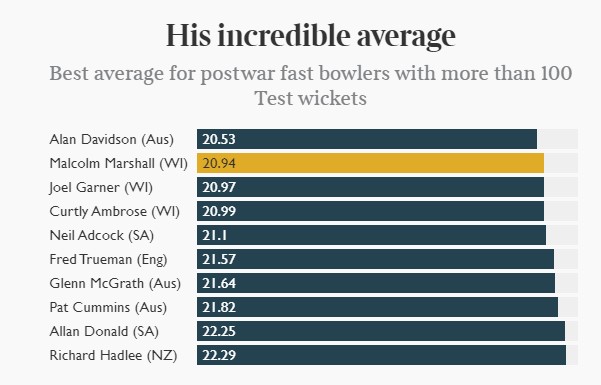

His statistical record, for those who judge on numbers alone, stands comparison with any. Of those fast bowlers who have taken more than 100 Test wickets, you have to go back to the late 19th century and early 20th century — when pitches were devilish and batting more rudimentary — to find bowlers with a considerably better bowling average. Only one postwar fast bowler — Alan Davidson, the Australia left-armer — has claimed his Test wickets at a cheaper rate than Marshall, who took 376 wickets at 20.94 in Test cricket and 1,651 wickets at 19.10 in the first-class game overall. Remarkable.

And there is no weak link in those numbers: he took his wickets at a little over 19 a piece against England, a little over 22 against Australia and somewhere in between against the rest, and all over the world. (Dennis Lillee, the great fast bowler who would be championed as the best by Australians, never played in India, and rarely in other parts of the sub-continent and the Caribbean.) Marshall looked upon bowling as an art and craft and would have been affronted by the notion that the sub-continent was no place for a fast bowler.

He played, arguably, in the greatest team the game has seen and was central to maintaining West Indies’ run as unofficial world champions. They never lost a series with their champion bowler in the team and lost only nine Tests in all during Marshall’s career, of which five came in his last 15 Tests. He had the fiercest pride, never better displayed than during a Test at Headingley in 1984, when he batted one-handed because of a broken thumb to see Larry Gomes to a century, and then destroyed England with seven for 53, his non-bowling hand supported in a cast.

Fast, skilful, intelligent, full of heart and determination, he was the complete package.

Dennis Lillee

by Simon Wilde

The great era of fast bowling of the 1970s and 1980s was built on the example of two men, Dennis Lillee and Andy Roberts, who pointed the way through their performances on the field and the advice they shared off it. They were not only in their prime very fast bowlers, but also master technicians. But of the two, Lillee was at the top level the more complete, driven and durable.

Lillee was held in the highest regard by those who followed, whether the Australians who played alongside him, the Englishmen he tormented, or others such as Malcolm Marshall, the best of the Caribbean quicks after Roberts, or Imran Khan from Pakistan. Marshall credited Lillee among his greatest influences and earned his lasting gratitude for teaching him the leg-cutter (which Marshall then passed to Imran).

It was no surprise that when he finally retired aged 39, after demonstrating during a farewell season at Northamptonshire in 1988 that he had lost none of his guile, Lillee became an accomplished coach. Nor did he take the easy gigs. He set up an academy in India, which had a thin tradition of fast bowling, with impressive results. Nearer to home, he helped put Mitchell Johnson, a fellow West Australian, on track.

These days, fast bowlers have their workloads managed, and their bodies fine-tuned like racing-car engines. In Lillee’s day, when the game was semi-professional (with the emphasis on the semi), they were on their own. They played more and broke down more; only the smart survived. When Lillee retired from Tests, his haul of 355 wickets was a world record and viewed with general astonishment. This takes no account of the two and a half years of Test cricket he missed during the World Series breakaway. Kerry Packer recruited many of the world’s best fast bowlers but Lillee remained the stand-out with 67 wickets in 14 “Super Tests”, well clear of Roberts on 50. Ludicrously, the authorities still deny these contests first-class status.

Another measure of Lillee’s greatness was his record against Viv Richards, then the world’s best batsman, dismissing him nine times in Tests — more than anyone else — and seven times in “Super Tests”. Once, during World Series, he got a bouncer through Richards’s defence and struck him on the jaw. Richards shook his head and carried on, but undoubtedly his pride was stung.

When Lillee entered the game in the late Sixties, there were few from whom he could learn his craft. Australia had been looking for an out-and-out fast bowler since Alan Davidson retired in 1963. The great Ray Lindwall advised him on aspects of his run-up, but otherwise he had to learn on the hoof. He had raw pace from the start but a season in the Lancashire League in 1971 taught him the need for accuracy and movement off the pitch. The following year he took a then Australia record of 31 wickets in a series in England.

He played 26 of his 70 Tests alongside Jeff Thomson, who for a couple of years was devastating in Australian conditions, but Thomson was rarely the same bowler overseas and otherwise new-ball partners came and went with alarmingly frequency. Lillee was always the spearhead, always the guiding light.

He had a heart the size of a lion. Shaped by 18 months out of the game rebuilding his back from multiple stress fractures, his attitude was that fast bowling was hard work and involved never countenancing defeat. Witness his refusal in December 1976 to accept that Western Australia could not win after being bowled out for 77 in a one-dayer against Queensland: after dismissing Richards, Queensland’s overseas star, for a duck, he duly bowled his side to an astonishing victory.

Witness, too, how two weeks later in a Test in Adelaide during which Thomson ruptured his shoulder and Gary Gilmour succumbed to a foot infection, he got through 66.7 eight-ball overs, more deliveries than any fast bowler has sent down in any Test match in the last 50 years.

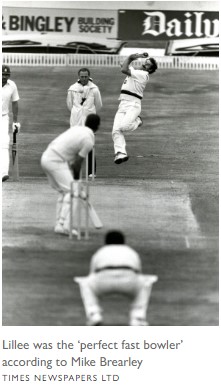

Mike Brearley described Lillee as “the perfect fast bowler: genuinely quick, hostile and accurate”. What he also had — apart from an immaculate technique, including one of the greatest run-ups the game has seen — was a sense of theatre, a willingness to engage with the crowd and his opponent standing 22 yards away. He was a gladiator in an era when TV cameras began zooming in on protagonists’ faces like never before. Lillee fully repaid the watching.

Other notable contenders: Wasim Akram, Glenn McGrath, Sydney Barnes, Curtly Ambrose, Fred Trueman, Harold Larwood, Ray Lindwall and Jimmy Anderson

No Comments