OVERVIEW OF THE AIR FORCE OFFICER CORPS | GD/P BRANCH AND KEY FLYING ACTIVITIES DURING THE PERIOD 1982 TO 1991 – Compiled by: Gp Capt Kumar Kirinde (Retd)

With reference to and contents extracted from:

- The Sri Lanka Air Force: A Historical Retrospect 1985 – 1997 (Vol. II) by Jagath P Senaratne with foreword by ACM O M Ranasinghe, Commander of the Air Force, 1994 to 1998 (Primary Source)

- China Bay and Morawewa 1959-1999 by Wg Cdr Ranjith Ratnapala

- The History of the Sri Lanka Air Force (Vol. I) by Nalin Wijesekara, V. Tennekoon & Mervyn De Silva

- Wings of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka Air Force, Fifty Years’ Service to the Nation 1951-2001 by Rienzi Pereira

- Sri Lanka Air Force 60th Air Force Day Souvenir

- Air Force List

SLAF

ACKNLOWLEGEMENTS

Air Cdre Kithsiri Leelaratne (Representative for RAFOA, AFHQ) Air Cdre Nihal Jayasinghe (CO, SLAF Museum, Ratmalana)

RAFOA

Wg Cdr Ranjith Ratnapala

CONTENTS

1. GD/P BRANCH OFFICERS AS PER THEIR FLIGHT CADET/TRAINING COURSES 1982 TO 1991 – Page 4

2. SLAF AIRCRAFT IN OPERATION FROM 1982 TO 1991 – Page 8

3. “THOSE WHO DID NOT RETURN TO BASE” – SLAF PILOTS WHO DIED IN AIR CRASHES DURING 1982 TO 1991 – Page 10

4. KEY FLIYING ACTIVITIES DURING 1982 TO 1991 – Page 11

ANNEXURES

A. AN INTERESTING ENCOUNTER WITH A RPG – DEC 1986, Page 22

B. BATTLE DAMAGE DURING SUPPORT OF VVT ARMY CAMP – APR 1987, Page 24

C. NIGHT HELICOPTER MISSION – JUL 1987, Page 26

D. CRISIS DURING MEDICAL EMERGENCY FLIGHT – JUN 1989, Page 28

E. OPERATION EAGLE – JUL 1990, Page 34

F. SLAF ASSISTANCE DURING THE ATTACK AGAINST SILAVATTURAI CAMP – MAR 1991. Page 40

G. CESSNA 337 ENGINE FAILURE – NOV 1991, Page 42

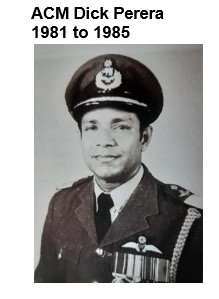

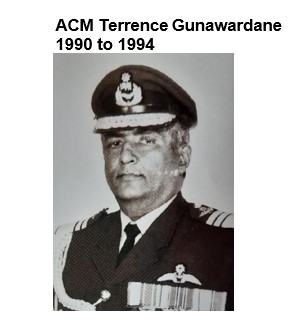

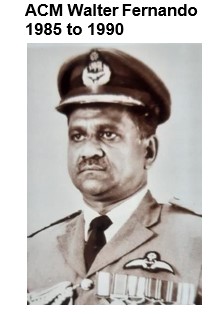

COMMANDERS OF THE SLAF 1982-1991

NO. 21 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1982

(Members of No 10 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01407 | ACM | K V B Jayampathy | GD/P | 05/03/1982 |

| 01408 | Sqn Ldr | B R E Mendis | GD/P | 05/03/1982 |

NO. 22 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1983

(Members of No 11 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01422 | Sqn Ldr | T C B J Thibbotumunuwe | GD/P | 18/04/1983 |

| 01423 | Fg Off | H T T K Seneviratne | GD/P | 18/04/1983 |

NO. 23 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1984

(Member of No 12 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01424 | Flt Lt | P K Cumaratunge | GD/P | 09/05/1984 |

| 01425 | Fg Off | B N P A Fernando | GD/P | 09/05/1984 |

NO. 24 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1984

(Members of No 13 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01447 | Gp Capt | P Gunasinghe | GD/P | 12/12/1984 |

| 01448 | Air Cdre | SR Gunaratne | GD/P | 12/12/1984 |

| 01449 | ACM | DLS Dias | GD/P | 12/12/1984 |

| 01450 | Plt Off | M S Buhary | GD/P | 12/12/1984 |

| 01451 | Sqn Ldr | A P W Fernando | GD/P | 12/12/1984 |

NO. 25 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1986 / NO. 32 ALLIED GD/P COURSE AT PAKISTAN AIR FORCE RISALPUR – 1986

(Members of No 14 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01473 | Wg Cdr | RY Senanayake | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01474 | Gp Capt | W L M J P Rodrigo | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01475 | AVM | HMSKB Kotakadeniya | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01476 | Sqn Ldr | SAKS Rathnasekara | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01477 | AVM | PDKT Jayasinghe | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01478 | Sqn Ldr | BNPK Kumbalatara | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01479 | Wg Cdr | K P Weeraman | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01480 | Wg Cdr | SMD Wijeyasooriya | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01496 | AM | S K Pathirana | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01497 | Wg Cdr | IJI Wijetileke | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

| 01498 | Sqn Ldr | S Pathiratne | GD/P | 02/07/1985 |

NO. 26 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1986 / NO. 33 ALLIED GD/P COURSE AT PAKISTAN AIR FORCE RISALPUR – 1986

(Members of No 15 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01499 | Gp Capt | S P Adikaram | GD/P | 16/12/1985 |

| 01500 | Flt Lt | R B Kulatunge | GD/P | 16/12/1985 |

| 01552 | Gp Capt | H Hendavithrana | GD/P | 16/12/1985 |

| 01553 | Wg Cdr | S R S De Silva | GD/P | 16/12/1985 |

| 01554 | Sqn Ldr | P M Mahamalage | GD/P | 16/12/1985 |

| 01555 | Sqn Ldr | K A J P Kahandawala | GD/P | 16/12/1985 |

| 01556 | Wg Cdr | AP Mirando | GD/P | 16/12/1985 |

NO. 27 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1986

(Members of No 16 Officer Cadets’ / KDA intakes)

| 01501 | Sqn Ldr | T C Kaluarachchi | GD/P | 18/05/1986 |

| 01502 | Wg Cdr | T D S Silvapulle | GD/P | 18/05/1986 |

| 01503 | AVM | D K Wanigasooriya | GD/P | 18/05/1986 |

| 01504 | Flt Lt | A P Peiris | GD/P | 18/05/1986 |

| 01519 | Flt Lt | P Abeyweeragunawardena | GD/P | 18/05/1986 |

| 01534 | Sqn Ldr | D S Thalagala | GD/P | 18/05/1986 |

| 01551 | Gp Capt | M R Kurukulasuriya | GD/P | 02/06/1986 |

| 01557 | AVM | M D A P Payoe | GD/P | 18/05/1986 |

NO. 28 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1987

(Members of No 17 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01563 | Flt Lt | N W Gamage | GD/P | 09/12/1986 |

| 01564 | Wg Cdr | U P Danwatte | GD/P | 09/12/1986 |

| 01565 | Gp Capt | RMPRSS Dharmawardana | GD/P | 09/12/1986 |

| 01566 | Sqn Ldr | S M Gamage | GD/P | 09/12/1986 |

NO. 29 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF CHINA BAY – 1987

(Members of No 18 Officer Cadets’ / KDA intakes)

| 01602 | Gp Capt | TPM Gunasekara | GD/P | 21/07/1987 |

| 01620 | Wg Cdr | M R C Thomas | GD/P | 15/05/1986 |

| 01636 | Wg Cdr | S J S Fernando | GD/P | 09/12/1986 |

| 01637 | Sqn Ldr | E A D Edirisinghe | GD/P | 09/12/1986 |

| 01638 | Flt Lt | S P Herath | GD/P | 09/12/1986 |

NO. 30 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF ANURADHAPURA – 1988

(Members of No 19 Officer Cadets’ / KDA intakes)

| 01640 | Flt Lt | C C Ratnapala | GD/P | 17/05/1988 |

| 01641 | AVM | R P Liyanagamage | GD/P | 17/05/1988 |

| 01642 | AVM | H S S Thuyakontha | GD/P | 17/05/1988 |

| 01695 | AVM | RAUP Rajapaksa | GD/P | 06/10/1988 |

| 01696 | Flt Lt | M V K B H Wijayakoon | GD/P | 06/10/1988 |

| 01697 | Wg Cdr | V C Senarathne | GD/P | 06/10/1988 |

| 01698 | Wg Cdr | HEMPB Ekanayake | GD/P | 06/10/1988 |

NO. 31 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF ANURADHAPURA – 1989

(Members of No 20 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01763 | Wg Cdr | D T K Weligodapola | GD/P | 05/04/1989 |

| 01764 | Sqn Ldr | S R J De Mel | GD/P | 05/04/1989 |

| 01765 | Wg Cdr | S A D Wijeratne | GD/P | 05/04/1989 |

| 01766 | Flt Lt | D F D S Perera | GD/P | 05/04/1989 |

| 01767 | Fg Off | U T Goonatilleke | GD/P | 05/04/1989 |

| 01842 | Flt Lt | SV Perera | GD/P | 05/04/1989 |

NO. 32 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF ANURADHAPURA – 1990

(Members of No 21 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01837 | Sqn Ldr | M T P Salgado | GD/P | 04/10/1989 |

| 01838 | Wg Cdr | N L S Wijesekara | GD/P | 04/10/1989 |

| 01839 | Fg Off | A M A Packeer | GD/P | 04/10/1989 |

| 01841 | Wg Cdr | KN Weerakoon | GD/P | 04/10/1989 |

NO. 33 FLIGHT (OFFICER) CADETS COURSE AT SLAF ANURADHAPURA – 1991

(Members of No 22 Officer Cadets’ intake)

| 01845 | Flt Lt | A Malalasekara | GD/P | 05/10/1990 |

| 01847 | Sqn Ldr | S P Kaluarachchi | GD/P | 05/10/1990 |

| 01852 | Flt Lt | M Abeywickrama | GD/P | 05/10/1990 |

| 01853 | Flt Lt | D T Gunasekara | GD/P | 05/10/1990 |

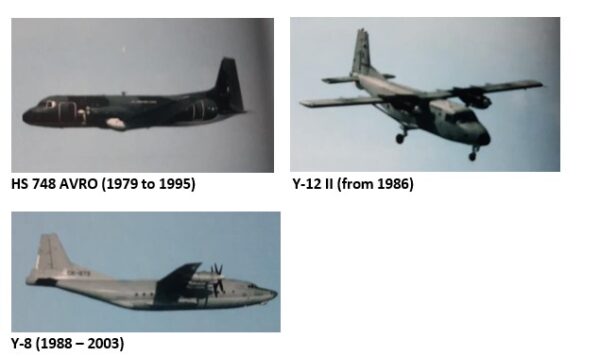

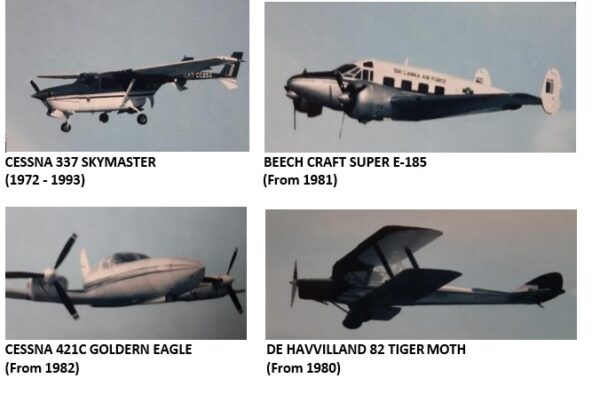

AIRCRAFT IN OPERATION FROM 1982 TO 1991

TRAINER AIRCRAFT

TRANSPORT AIRCRAFT

FIGHTER JETS

LIGHT ATTACK AND EXPERIMENTAL AIRCRAFT

UTILITY AIRCRAFT

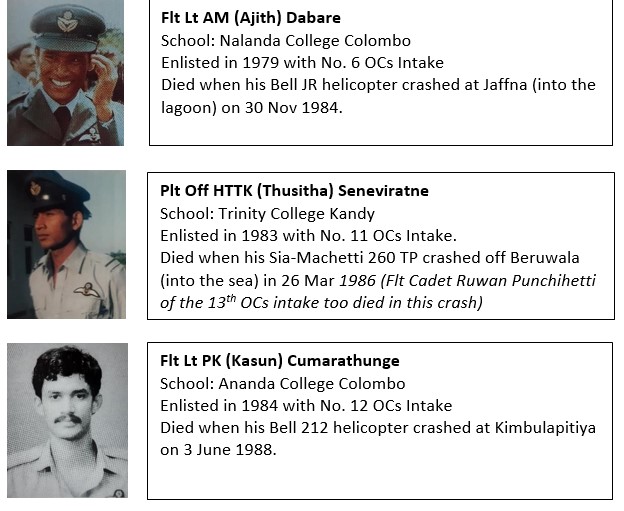

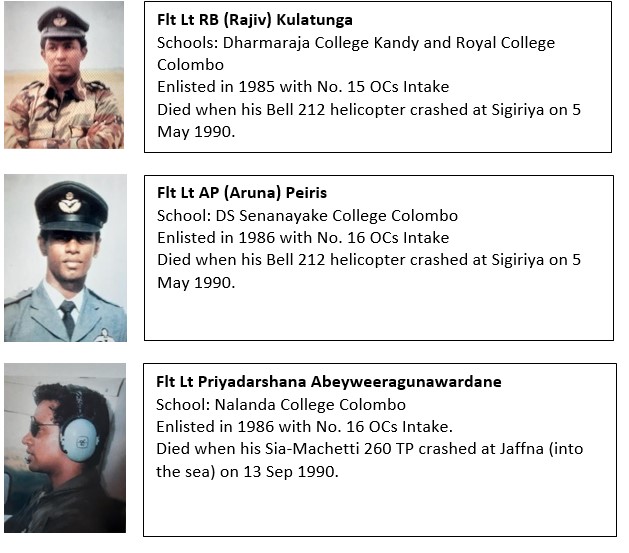

“THOSE WHO DID NOT RETURN TO BASE”

SLAF PILOTS WHO DIED IN AIR CRASHES DURING 1982 TO 1991

KEY FLYING / FLYING RELATED ACTIVITIES DURING 1982 to 1991

1982

- Work started to re-activate disused airfilelds which were now vested under the control of the SLAF. These were airfields at Weerawila, Vavuniya, Anuradhapura, Batticaloa, Sigiriya, Koggala an

1983

- Two member team from RAF’s Central Flying School (CFS) examined and categorised Flying Instructors, standardised flying on various types of SLAF aircraft and conducted Instrument Rating Tests on SLAF

- Under the Overseas Flying Programme four (4) Overseas flights were carried

- The 4 Squadron participated in some military excercises cxonducted by the SLAF Regiment and the Army

- A fixed-wing transport aircraft, BAe 748 Avro was also added to the SLAF’s

- SLAF Air Field Unit, Palaly was established on one side of the civil airport

- A Bell Jet Ranger helicopter was also provided to SLAF, Air Field Unit, Palaly for reconnaisance duties and air liaison work when requested by Army’s Security Forces Commander in Jaffna

- Joint Services Special Operations (JOSSOP) HQ was formed in Vavuniya and for the use of its Commander a helicopter was attached to SLAF, Air Field Unit,

- Air transport of cash and valuables were done on behalf of banks. The respective banks paid for these

1984

- In order to meet the increased demands of the Army for SLAF support consequent to the considerable increase in Tamil seperatist insurrection another Bell Jet Ranger and one of the newly aquired Bell 212 helicopters were attached to

- A Bell Jet Ranger Helicopter was attached to SLAF, AFU, Batticaloa for the use of Coordinating Officer and for AOP (Air Observation Post), reconnaisance and air liaison

- The helicopters assigned for AOP, reconnaisance and air liaison work in operational areas also became involved in limited logistic support of forward based army camps when road transportation was impeded by land mines and

- The Bell Jet Ranges positioned in Jafna and Batticaloa were armed for the first time withforward firing machine guns in pods, or rocket

Bell Jet Ranger

- Scheduled flights by fixed-wing aircraft to Jaffna increased to transport armed forces personnel to and from the peninsula. Additional flights were also required for the transportation of fresh rationsto

- Four (4) Bell 212 helicopters – including two (2) which could be configured as gunships were inducted.

Bell 212

- Flights to ferry troops for operations and ration transportation to Vavuniya and Batticaloa were also carried out as and when

- A considearable number of CASEVAC flights were carried out by both helicopters and fixed- wing aircraft during the year. In many of these instances the helicopters brought, to an airfield, the wounded personnel from a camp or the At the airfield the casualty would be transferred to a fixed-wing aircraft. However, either when a ixed wing aircraft was not availble or for some other urgent reason the helicopter could also rush the patient straight to a nearby hospital for medical attention.

1985

- A total of ten (10) Bell 212 helicopters and six (6) Siai-Machetti SF 260 TP light ground- attack aircraft were inducted during the year

- The Cessna 337 attached to Palali remained for land and sea surveillance and communication missions.

Cessna 337

- A total of 15 pilots were converted to fly the Siai-Machetti SF 260 and a limited number of sorties on gunnery traning was carried out with the help of an instructor provided by the

- Close Air Support (CAS) training missions were carried out succesfully by pilots concerened on Bell 212 helicopter gunships and Siai-Machetti light ground attacke aircraft at the Kalpitiya air firing range using the forward firing .50-inch calibre machine guns and 2.75-inch

- Bell Jet Ranger single engine helicopters attached to Jaffna, Vavuniya and Batticaloa were replaced by twin engined Bell

- The Bell 212 helicopter gunship which was based at Batticaloa assisted in Operations in liasion with the Army and the STF (Special Task Force of the Police).Air cover for groung combat troops, casualty evacuation, troop transportation, VIP/VVIP conveyance, and air reconnaisance were undertaken from

- A helicopter was attached to Sir Force Academy China Bay for use by the coordinating officer of Trincomalee.

- A total of four (4) Bell 412 helicopters were inducted during the year

Bell 412

1986

- The Joint Operations Command (JOC) was established replacing the JOSSOP and the operational use of aircraft was increasingly coordinated through this

- Three (3) new Bell 212 helicopters, one (1) BAe-748 Avro aircraft, two (2) Siai-Machetti SF 260 light ground-attack aircraft, and two (2) Y 12 light transport aircraft were inducted.

- Air Force in support of Operations Short Shrift 1 and 2 launched by thr Army, carried out air reconnaisance, CAS (Close Air Support), CASEVAC and AOP (Air Observation Point) CAS wwas provided by SF 260, Bell 212s and Bell 412s

1987

- In support of Operation Liberation, the the biggest military operation undertaken upto that time by the Sri Lanka armed forces, the SLAF allocated a large fleet of aircraft, a total of 35 as given below. This by far is the largest number of aircraft ever devoted to a single Operation upto that time.

- Six (6) Siai-Machetti SF 260s for Fighter Ground Attack (FGA) operations coordinated by FACs (Forward Air Controllers), carried out both CAS and Battlefield Interdiction

- Two (2) Bell 212 helicopters configured as gunships provided

- Eight (8) helicopters configured as troop-carriers transported heavily armed army troops to various locations on the

- Two (2) helicopters were configured for both troop carrier-cum CASEVAC

- Three (3) helicopters configured as troop-carriers were held in reserve and used when

- One (1) BAe HS 748 Avro, two (2) Y 12s and one (1) De Havilland Heron were configured as improvised

- Two (2) BAe HS 748 Avros, two (2) Y 12s and two (2) De Havilland Doves worked as transports ferrying goods and

- One (1) Y 12 was kept devoted for CASEVAC

- Three (3) Cessna 337s were devoted for both over land and sea

In addition to above listed, Bell Jet Ranger helicopters did many AOP flights, ofen carrying senior officers of the JOC in them.

- With the emergence and escalation of insuregent activities in the South a helicopter was stationed at SLAF Air Field Unit,Weerawila.

- Four (4) Y-8 transport aircraft were inducted.

Y 8

1988

- Four (4) helicopters were deployed in the Northern areas, and one (1) helicopter was stationed at AFU Weerawila to assist anti-subversive operations.

- During the year air force aircraft were called to fly CASEVAC missions to all parts of the island.

- Three (3) Siai-Machetti SF260 TP aircraft were added to the Fleet.

- Tiger Moth Aircraft which was rebuilt over a number of years was completed and flown.

Tiger Moth

- With the reduction of operational flying consequent to the arrival of the IPKF, SLAF commercial operations, Helitours showed a marked increase in revenue genaration.

1989

- With the gradual withdrawal of IPKF from July, SLAF aircraft were heavily committed to ferrying of personnel and cargo in support of Army troops and Police deployment to the North and East.

- Deployment of fixed wing aircraft and helicopters increased in the North, East and Southern areas of the country.

- CASEVAC missions were flown to key hospitals within the island.

1990

- Two months after the IPKF left the Island in March 1990, the separatist insurrection was reignited by the LTTE in early June with attacks against numerous army camps and police establishments in both the North and East. Once fighting started the SLAF carried out a range of missions such as CASEVAC, food and ammunition drops into besieged camps, maritime reconnaissance, bombing LTTE camps and supply dumps and Close Air Support (CAS) to ground troops on operations as listed below.

Operations Sledge Hammer 1 and 2 – From 15 June 1990 in Batticaloa and Ampara Districts onwards to recapture areas and towns under the control of the LTTE. SLAF role: ground-attack, helicopter fire-support, food drops, logistic support, and CASEVAC.

The siege on Jaffna Fort developed to a very serious level at this time, and it was in this context the SLAF planned and executed Operation Eagle on 3 July 1990 (please refer page….for a detailed account of this special air operation)

Operation Gajasinghe – From 19 July 1990 onwards, in Kilinochchi District, to reinforce and link up with the Kilinochchi Army Camp. SLAF role: ground-attack, helicopter fire-support, and CASEVAC.

Operations Thrivida Balaya 1 – From 20 August 1990 onwards, in Kayts and Mandaitivu Islands in Jaffna, aimed at linking up with the besieged troops in Jaffna Fort and to carry out an orderly withdrawal. SLAF role: ground-attack, helicopter fire-support, re-supply of ammunition and food drops into the Fort, and CASEVAC. During the operation an SLAF pilot was killed while on a ground –attack mission. Events leading to the death is recorded as following.

“On 13 September Fg Off P Abeyweeragunawardane was flying a Siai-Marchetti SF 260TP (Serial No. CT-121) ground-attack aircraft in the area. There were other SF-260s and helicopters in the area which were also involved on CAS missions. On one of his dives, when attacking LTTE fire”.

.50-inch calibre machine gun positions around the Fort, his aircraft was hit by machine gun fire from the ground. Eyewitness, among whom were SLAF helicopter pilots who were on ground on Mandaitivu Island, saw his aircraft flying very low, strafing, when it was hit by gunfire. The aircraft when into a shallow climb, stalled and then crashed into the sea between Mandaitivu Island and Jaffna Fort. The pilot died in the crash. Fg Off P Abeyweeragunawardane was the first SLAF pilot to be killed in action as a direct result of LTTE fire”.

Operation Oyster – From 1 September 1990 onwards, in Kilinochchi District, to attack LTTE bases in Pooneryn area and regain control of area. SLAF role: Six (6) helicopter troop carriers, two (2) helicopter gunships and two (2) Y-12s.

Operation Sea Breeze – From 1 September 1990 onwards, in Mullaitivu District, to link-up with and strengthen Mullaitivu army, and facilitate CASEVAC SLAF role: Ground-attack by SF 260s, troop lift by Y-8, bombing by Y-12, and seven (7) helicopter troop carriers and gunships.

Operations Thrivida Balaya 2 – From 15 October 1990 onwards, in Jaffna, to capture and consolidate areas on Kayts Island. SLAF role: Six (6) SF 260s for ground attack, two (2) helicopter gunships, two (2) helicopter troop carriers and two (2) Y-12s as bombers.

Operation Jayasakthi – From 17 to 23 October 1990, FDL expansion in Jaffna peninsula. SLAF role: Ground-attack, air reconnaissance, and troop lift by helicopters.

In addition to these operations the SLAF also came to the assistance of many army camps like Mankulam, Kokavil, Kiran, and Kilinochchi which were subjected to attacks by the LTTE.

- One (1) overseas flight, Colombo-Male-Colombo was done on 21 November 1990.

- Siai- Marchetti SF 260 W Warrior light attack/trainer aircraft, the piston engine version of the SF 260 TP was inducted to the aircraft fleet during the year.

1991

- In the beginning of 1991 fast jet aircraft re-entered into SLAF service with the induction of two FT-5 jet trainers, one (1) jet trainer, and four (4) single-seaters.

- Allocation of the aircraft from the total fleet to respective flying formations were as following,

No. 1 Flying Training Wing – Cessna 150s, Siai-Machetti SF 260W Warriors and Siai- Machetti SF 260TP light ground-attack aircraft.

No. 2 Transport Wing – Y 8 heavy transports, BAe 748 Avro medium transports and Y 12 light transports.

No. 3 Maritime Squadron – Cessna 337s.

No. 4 Helicopter Wing – Bell 206 Jet Rangers, Bell 212s and Bell 412s

- In 1991, the Army carried out a series of operations in both the North and the East. The air support given by the SLAF for these operations are as given

Operation Tiger Flush – From 13 January 1991, in Thoppigala area, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: Two (2) ground-attack aircraft, two (2) helicopter gunships and one (1) helicopter for CASEVAC.

Operation Tiger Hunt – From 29 March to 1 April 1991, in Tirikonamadu area, Polonaruwa District.

SLAF role: One (1) helicopter gunship and one (1) helicopter for CASEVAC.

Operation Royal Flush – From 5 to 9 April 1991, in Thoppigala area, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: One (1) helicopter gunship and one (1) helicopter for CASEVAC.

Operations High Tide 1 & 2 – From 21 April 1991 onwards, in Jaffna to capture Karaituvu and Kayts Islands to secure Karainagar Navy Base.

SLAF role: Ground-attack aircraft and helicopter troop-carriers as required.

Operation Wanniwickrama 1 – From 2 May 1991onwards, north of Vavuniya, Vavuniya District.

SLAF role: One (1) helicopter gunship and one (1) helicopter troop-carrier and ground-attack aircraft as required.

Operation Ramdad –In May 1991, in Vavunatheevu-Kokkadicholai area, Batticaloa District. SLAF role: Two (2) helicopters for ground-attack and/or as troop-carrier, and one (1) Y 12 for bombing missions as required.

Operation Mixed Grill – From 11 June 1991 onwards, in and around Thoppigala area, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: One (1) helicopter gunship, two (2) helicopters for CASEVAC and troop-carrying, one (1) Y 12 for bombing, one (1) Cessna 337 for reconnaissance and ground-attack aircraft

Operation Wanniwickrama 2 – From 14 June 1991 onwards, in Periyathampanai area, Vavuniya District.

SLAF role: Two (2) fixed wing aircraft and two (2) helicopters for ground-attack (1) helicopter troop-carrier for CASEVAC and troop- transport.

Operation Black-Panther – From 21 June 1991 onwards, north of Batticaloa town, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: Fixed wing ground-attack aircraft, three (3) helicopters for CASEVAC and dropping of troops, and one (1) Cessna 337 for reconnaissance.

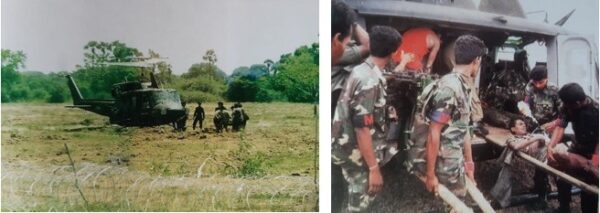

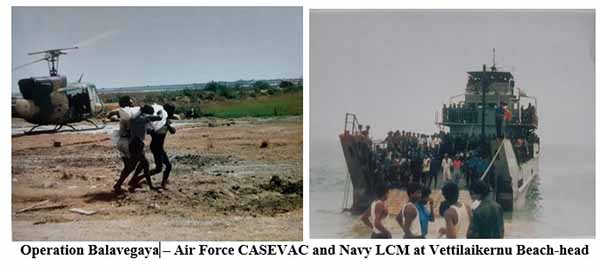

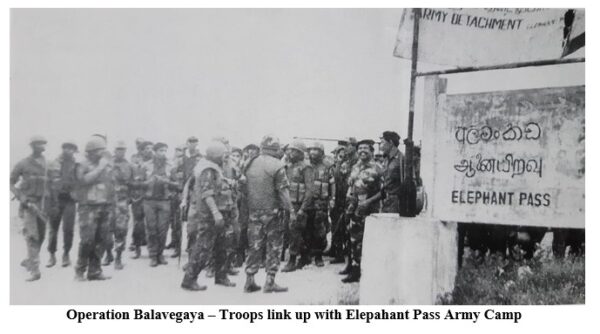

Operation Balavegaya 1 – In July 1991, the LTTE encircled the Elephant Pass army camp and laid siege to the camp. There were approx. one (1) Battalion of troops in the camp and if they were to be saved a rescue operation had to be launched. The Army’s rescue operation, Operation Balavegaya 1, began on 14th July and lasted till 19th August 1991. Its object was to land a strong force at Vettilaikerni beach, break through LTTE resistance and link-up with Elephant Pass army camp and relieve its troops. This task was eventually completed.

SLAF role: Six (6) ground-attack aircraft, Four (4) Y-12s for food drops into the camp and for bombing LTTE positions, four (4) helicopters as troop-carriers and one (1) Cessna 337 for reconnaissance.

Operation Ashakasena – From 15 July 1991 onwards, in Welioya general area, Mullaitivu District.

SLAF role: Fixed wing ground-attack aircraft and helicopters for CASEVAC.

Operation Akunupahara – From 29 August 1991 onwards, in the LTTE’s 1-4 base area, Mullaitivu District.

SLAF role: Fixed wing ground-attack aircraft as required, Y 12 for AOP, Y 8 for bombing Two

- helicopter gunships and (two) 2 helicopter troop-carriers.

Operation Seal Off – From 14 to 16 October 1991, to establish 2 bases of Company strength to resist LTTE movement, in Kokkuttuduvai area, Trincomalee.

SLAF role: One (1) helicopter gunship, one (1) helicopter troop-carrier for recee and CASEVAC. Fixed wing ground-attack aircraft, Y 12 and Y 8 as required.

Operation Valampuri 1 – From 18 to 19 October 1991, to clear and hold Pungudutivu Island, Jaffna District. SLAF role: Six (6) fixed wing ground-attack aircraft, two (2) Y 12s, two (2) helicopter gunships, two (2) helicopter troop-carriers and one (1) Cessna 337 for recee as required.

Operation Valampuri 2 – On 22 October 1991, amphibious landing in Pooneryn, Kilinochchi District.

SLAF role: Six (6) fixed wing ground-attack aircraft, two (2) Y 12s, two (2) helicopter gunships, two (2) helicopter troop-carriers and one (1) Cessna 337 for recee as required.

Operation Akal Vessa – On 22 October 1991, amphibious landing in Pooneryn, Kilinochchi District.

SLAF role: Six (6) fixed wing ground-attack aircraft, two (2) Y 12s, two (2) helicopter gunships, two (2) helicopter troop-carriers and one (1) Cessna 337 for recee as required.

Operation Daybreak – On 23 to 25 November 1991, in Kalayadimadu, Batticaloa District. SLAF role: One (1) helicopter gunship and one (1) helicopter troop-carrier.

Operation Watarauma – On 26 November to 3 December 1991, in Thoppigala area, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: Two (2) fixed wing ground-attack aircraft and two (2) helicopter gunships.

Operation Green Belt – From 3 December 1991, in Veppankulam area, Mannar District.

SLAF role: Fixed wing ground-attack aircraft, helicopter gunships and Y 12 aircraft.

Operation Rhino – From 7 December 1991, in Paddiruppu area, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: One (1) helicopter gunship and one (1) helicopter troop-carrier.

Operation Black Fox – From 22 to 23 December 1991, FDL expansion operation, to clear and hold Nelukkulam area, Vavuniya District.

SLAF role: Two (2) fixed wing ground-attack aircraft, One (1) helicopter for CASEVAC.

Operation Buwalla – From 26 to 27 December 1991, in Karavaddi area, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: One (1) helicopter for fire support and if necessary for CASEVAC.

Operation Kande Gedara – From 30 December 1991 to 2 January 1992, in Thoppigala area, Batticaloa District.

SLAF role: Two (2) fixed wing ground-attack aircraft and two (2) helicopters for troop transport and CASEVAC.

AN INTERESTING ENCOUNTER WITH A RPG 1986

Extracted from “The Sri Lanka Air Force: A Historical Retrospect 1985 – 1997 (Vol. II)” by Jagath P Senaratne (with foreword by ACM Oliver Ranasinghe, Commander of the Air Force, 1994 to 1998)

On 18 December 1986, a Bell 412 helicopter, serial number CH-523, based in Vavuniya, was scheduled to carry-out a routine logistic-support flight to Mannar. These logistic flights supplied the respective camps with some fresh rations, and also transported Government personnel on leave to and from these camps. The crew consisted of Fg Off G.P. Bulathsinghala, his co-pilot Off Cdt HMSKP Kotakadeniya, and two door gunners. Due to the difficulties of road transportation such logistic flights were flown from Vavuniya to Mannar (westwards), Omantai, Mankulam, Kokavil, and Kilinochchi (northwards), and Oddusudan and Mullaittivu (northeastwards). On that day the flight was westward to Mannar.

The helicopter took off normally from Vavuniya with a load of passengers and proceeded towards Mannar. After about 20 minutes of flying, the pilots suddenly saw a blue coloured truck on a gravel road below them. They descended and saw that it was an Isuzu Elf open truck carrying some cargo, and that there were also some armed people in it. Hearing the helicopter, the truck started to increase speed. This truck had to belong to one of the separatist insurgent groups as there were no army personnel in the area. The pilots quickly decided to attack the truck – attacking targets of opportunity was a standard element of any flight over insurgent dominated territory – and the gunners were given the order to fire at the truck. The door gunners opened fire at the truck, and the people in the truck also fired back at the helicopter. After a few moments the truck screeched to a halt and the insurgents jumped out, abandoned the truck and ran into the thick jungle which bordered the road. The pilots discontinued the attack and proceeded towards Mannar.

The helicopter reached Mannar and the passengers disembarked and the rations were off- loaded. In a few minutes another group of 9 passenger embarked, and the helicopter immediately lifted-off. The pilots set course back to Vavuniya. When they reached the general area where the truck had been abandoned they suddenly noticed that it had been moved to a nearby location. The pilots again decided to attack the truck because it seemed to be carrying some vital cargo. As the cargo may include ammunition the door gunners were instructed to use tracer rounds.

The helicopter attacked the truck but after some moments the left door gunner’s weapon got jammed. While the gun was being rectified the captain gave the controls to his co-pilot, and then the right-hand door gunner opened fire. In the meantime the truck was hit by machine gun fire from the helicopter, and there was also some small-arms fire coming at the helicopter from the jungle below.

Suddenly, there was a very loud bang, and the aircraft became very difficult to control. The rotor RPM began to drop and all red lights and caution warning lights on the instrument panel came on. The audio warning began to sound loudly, adding to the urgency in the cockpit. The Captain immediately took over the controls and the co-pilot gave him all assistance. Both pilots communicated with each other through their helmet intercom system. As both pilots struggled with the controls they initially thought both engines were about to fail, in which case they would have to force land immediately. In the meantime the door gunners called over the intercom and reported that firing was coming from the jungle below them.

As the pilots checked and re-checked their instruments they realised that rotor RPM had not continued to keep on dropping, and that the noise of one engine kept at a constant note while one engine was winding-down. The pilots then realised that only one engine had failed and that they still had the other engine. The pilots then realised that they could make it back to Vavuniya. The aircraft was heavy but the pilots knew the capabilities of the Bell 412. The pilots carefully nursed the remaining engine, watching the temperature indicators, and proceeded in the direction of Vavuniya. By this time the helicopter had descended to around 700 feet of height.

After a few minutes the door gunners called out and said that the blue truck was proceeding behind them along the road, and that the insurgents in it were firing at the helicopter. In a little while the helicopter left the truck far behind, flew over the Vavuniya FDLs, and then made a single-engined landing at Vavuniya. Two persons in the helicopter had injuries: one was a civilian who worked at the Mannar army camp and whose arm was injured; the second was a door gunner with blood on his face as a consequence of some non-critical injuries. Both were rushed to hospital.

At Vavuniya airfield the helicopter was inspected by the pilots and SLAF engineering staff, and the cause of the damage was reconstructed as follows: an insurgent had fired a Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG) but in his haste had forgotten to remove the safety pin. The RPG round had come and hit the civilian’s arm, had then got deflected from its original path, brushed past the face of one of the door gunners, then hit the fire-wall at the rear of the cabin, gone through and cut the fuel lines and other connections to No.2 (i.e. starboard) engine, and had then embedded itself in the exhaust region of No. 1 engine. The warhead did not explode because the safety pin was still in place. Therefore, No. 2 engine was not seriously damaged but had failed due to fuel starvation. If the civilian’s arm had not deflected the RPG it would have hit the transmission region. The resulting damage to this area, even with the warhead not exploding would have been terminal and would have compelled the pilots to make a forced landing. Initially it was not clear that an RPG had been involved, but during the examination of the helicopter a piece of the warhead was found on the engine deck.

Hence, the helicopter had two narrow escapes: the first due to the safety pin not being removed; and the second due to the deflection off the civilian’s arm. Colonel Denzil Kobbekaduwa was in Vavuniya at the time and came to the helicopter and discussed the matter with the pilots. When shown the piece found on the engine deck he had confirmed that it was from a RPG warhead. He gave the pilots the RPG piece and told them to keep it as a souvenir, and then laughingly told them to send a thank you card to the person who had fired the RPG without removing the safety pin. The RPG pieces remain as souvenirs with the pilots to the present day.

*******************

BATTLE DAMAGE DURING SUPPORT OF VVT ARMY CAMP 1987

Extracted from “The Sri Lanka Air Force: A Historical Retrospect 1985 – 1997 (Vol. II)” by Jagath P Senaratne (with foreword by ACM Oliver Ranasinghe, Commander of the Air Force, 1994 to 1998)

On this particular day, 2 April 1987, Bell-212 serial number CH-537 was one of two helicopters detailed to assist troops in Velvettiturai (VVT) army camp which had come under attack by separatist insurgents. There were two helicopters at Palali at the time, and both took turns to assist the troops in the camp. The helicopters flew throughout the night, firing at areas directed by the army from within the camp. The camp was not overrun but the attack had been a narrow shave.

Then came first light and CH-537 was just getting ready to fly back to Palali when a 0.50-inch machine gun mounted on a double-cab vehicle was located. The pilots decided to attack, and flew at the target, firing the helicopters own forward mounted 0.50-inch machine gun. The machine gun on the double-cab too kept on firing back at the helicopter. Both guns were firing tracer bullets. For some moments the pilots remembered that it was as if the gun on the ground and the helicopter were exchanging tracer rounds. The helicopter kept on firing and dived at the target, coming in low. The co-pilot, as per standard procedure, kept on calling out the height to the Pilot. None of the double-cab’s bullets hit the helicopter.

Suddenly another 0.50-inch calibre machine gun began firing from one side of the helicopter. As the helicopter pulled up it was hit very badly. It appeared as if a complete burst had hit the aircraft. What appeared to be an explosion occurred inside the cockpit, and the co-pilot saw a fire inside under the Captain’s seat (subsequently it turned out to be a tracer bullet which was still glowing). The copilot’s helmet took a glancing shot and pieces of ceramic flew through the cabin. Pieces of ceramic and metal were later found embedded in the cabin padding. The aircraft seemed very badly hit, there was a reduction of power, the engines seemed to malfunction, and a severe vibration set in.

The aircraft was barely controllable and initially the Captain said that they would have to force land immediately in Velvettiturai camp itself. After discussion, this was decided against as the camp itself was under attack, and a forced landing inside the camp would merely add to the problems all around.

It was then decided to ditch in the sea, near a navy ship which was giving gunfire support to the camp from the sea. The ship was about 3 to 4 kilometers away. So the pilots flew the vibrating helicopter towards the ship. The pilots gave the Mayday call while nearing the ship. Then at a height of about 200 feet they discovered that the helicopter had stabilized and was flying level at a steady height but with very severe vibration. The vibration was so bad that the pilots could barely keep their eyes on any one object. The pilots canceled the Mayday call and decided not to ditch the helicopter, but try to get back to Palali airfield.

So the helicopter, emitting loud noises and vibrating very badly, proceeded slowly to Palali. The pilots skirted close to Thondaimannar army camp, intending to land at Thondaimannar if the aircraft’s performance suddenly worsened. But the Bell-212 kept on flying and they finally managed to struggle back to Palali and land safely.

*****************

NIGHT HELICOPTER MISSION

1987

Extracted from “The Sri Lanka Air Force: A Historical Retrospect 1985 – 1997 (Vol. II)” by Jagath P Senaratne (with foreword by ACM Oliver Ranasinghe, Commander of the Air Force, 1994 to 1998)

The following events occurred on the night of 5 July 1987 in Jaffna Peninsula, during the later stages of Operation Liberation (the Vadamarachchi Operation). During the night LTTE began to attack a camp at which the army had established in Nelliadi, in the premises of a school. During the course of the attack they fired Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPG), and used machine guns and small arms. The army personnel in the camp fought back. Most the soldiers of the camp had gone out on cleaning operation. Suddenly a vehicle laden with explosives was driven at high speed into the camp, and then blasted in the vicinity of the two storied building which was one of the strong-points of the defenders. As a result of the explosion the building collapsed, killing many army personnel in the process. Army resistance to the attackers continued from other locations in the camp. The soldiers who had left on the clearing operation were notified by radio and were moving back into the area. In the darkness, as they moved back they too became involved in firefights with LTTEers in the area.

In the meantime assistance was requested from the Air Force, and the two Bell-212s in Palali at the time became airborne immediately. One of the 212s was configured as a gunship, the other as a troop carrier. Both were armed and could give supporting fire to ground troops. They arrived overhead the besieged camp and gave whatever support they could to the defenders. As the gunship went back to Palali to refuel and get fresh ammunition, the troop carrier would take its place in the vicinity of the camp. Throughout the night the two helicopters supported the camp in this manner.

Below them, in the darkness, the helicopter pilots could see fires burning in several places. Because of the night, ground features and buildings could not be identified all that clearly, but after flying overhead for some time the layout of the camp became quite familiar to the pilots. The pilots were in radio contact with the soldiers who had begun to return to the camp, now under attack. The helicopter pilots tried to contact the camp, but initially there was no response.

A Voice from the Dark

Then, around 2300 hours, a voice suddenly came over the pilots’ radio headset. The caller gave his call sign, and identified himself as an army radio operator from the camp. The caller spoke very quietly and calmly, and informed the pilots that he had been in the building when the explosion took place, and that he was injured and trapped in the building. He was towards the edge of the rubble and could see out through the spaces between fallen pillar and rafters. He said that all the other soldiers with him were dead in the rubble around him. Somehow he had not got killed, and his radio was still working. He had switched it on and while going through the channels had located the ones being used by the helicopters.

The pilots were initially cautious of this voice from the dark, and asked for more details from the caller. The caller responded to all the questions regarding the camp. Then the pilots informed the army officers on the ground about the voice. The army officers wanted to be patched through on the radio to the soldier, and the pilots did so. Questions were asked, and the soldier’s identity was positively established. As recalled by the pilots, he was a radio operator from the 3rd Battalion, Sri Lanka Light Infantry (SLLI).

Then the radio operator began directing the pilots to specific targets which he could see. By this time LTTEers had penetrated into areas within the camp. The pilots recalled that the radio operator directed them to fire at specific locations where LTTEers had gathered, correcting their fire from the ground somewhat as a FAC (Forward Air Controller) would do. The pilots in the helicopters and the radio operator kept in intermittent contact with each other for several hours. When one helicopter flew back to Palali it would hand over the radio contact to the other which came to replace it. The situation was, as is usual in warfare, enveloped in the ‘fog of war’ and somewhat confusing. Concurrent to this contact between the radio operator and the helicopters, the LTTEers were ransacking parts of the camp, the returning soldiers were fighting their way back to the camp, and some LTTEers were acting as a rear-guard and resisting soldiers advance.

The pilots, in the meantime, kept in contact with both the radio operator and the returning soldiers. They also began to notice that the radio operator’s signals were getting fainter. When they inquired he said that his batteries were running low. He also said that he was feeling weak from his injuries.

From around 0300 hours on the next day, 6 July, the radio operator went off the air. The helicopter pilots tried many times to raise him but could not. The pilots think that he either succumbed to his injuries, or was captured by LTTEers (who themselves may have been monitoring the radio waves).

The pilots kept on flying throughout the night, and by dawn the LTTE began to withdraw from the camp. Later that morning the army returned to the camp.

****************

CRISIS DURING MEDICAL EMERGENCY FLIGHT

1989

Extracted from “The Sri Lanka Air Force: A Historical Retrospect 1985 – 1997 (Vol. II)” by Jagath P Senaratne (with foreword by ACM Oliver Ranasinghe, Commander of the Air Force, 1994 to 1998)

The following incident occurred on a flight captained by Fg Off S.K. Pathirana, with Plt Off P.M. Mahamalage as the Co-pilot. (They are referred to as Captain and Co-pilot in the following account.)

On the night of 13 June 1989, at China Bay air base, the pilots of No. 3 Maritime Squadron were relaxed and chatting with each other in the mess. They had finished dinner and all flying for the day had been completed. That particular night was gloomy and rain steadily beating outside the windows of the mess. The weather had turned bad that afternoon and all flying had terminated for the day. Even the reconnaissance flight usually done in the evening had been cancelled. The pilots relaxed in the mess, and after dinner went to their quarters looking forward to a good night’s sleep.

The Captain went to bed and was sound asleep when just after midnight there was a knock on his door. He instantly realised that this had to be a flying mission as otherwise a pilot would not be woken up in the middle of the night. He opened the door to find the then Commanding Officer of No.3 Squadron, Sqn Ldr C.R. Weerasinghe outside his door. His CO rapidly briefed him that a medical emergency had occurred on the Base which necessitated an immediate flight to Anuradhapura. An airman’s wife had given birth to a child and both were in a critical condition. The medical facilities in China Bay or Trincomalee town were inadequate to deal with the situation. If the mother and child remained in China Bay they would both not survive the night. The China Bay Doctor had recommended that the patients be flown immediately to Anuradhapura air base.

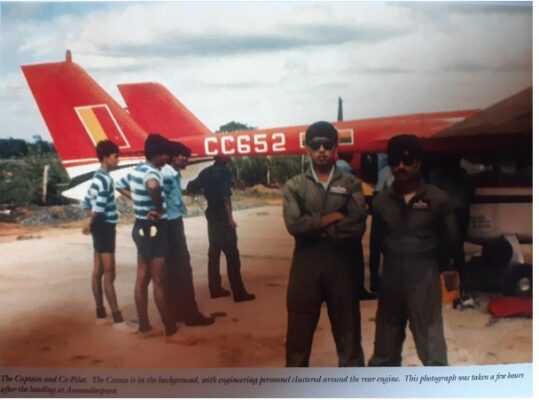

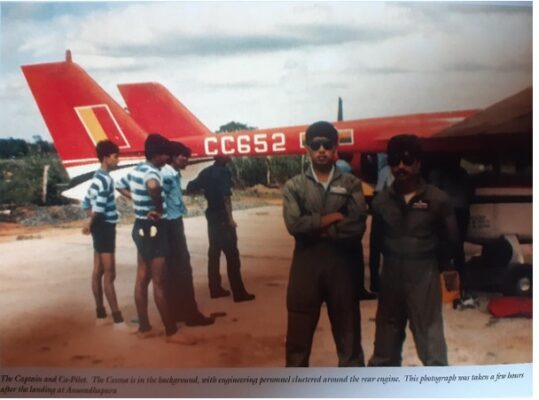

The CO requested Fg Off Pathirana, the duty pilot, to carry out the flight and nominated Plt Off Mahamalage as his c-pilot. Although the weather was bad, the situation necessitated this flight. The Captain agreed and quickly got dressed. In a few minutes the Captain and his copilot walked to the hangar area. On arrival they saw that a Cessna-337, serial no. CC652, had been pushed out and briskly prepared for the flight (note: this is the same aircraft which did a belly- landing at Katunayake in 1984). The Cessna-337 Skymaster is a twin-engined aircraft which was used in the Air Force for reconnaissance, CASEVAC, liaison and general utility missions. It can carry four passengers. The locations of its two engines are somewhat unusual in that one engine is at the front end of the fuselage, while the other is located at the rear. The tailplane and rudders were carried on two tail booms, thereby leaving space for the propeller of the rear engine. One advantage of this arrangement was that both engines provided their thrust along the axis of the aircraft.

The ground staff had quickly removed some of the rear seats and arranged the aircraft for a CASEVAC mission. Many officers and airmen were already present and were busily preparing the flight as they knew that every minute counted. The Weather was checked and although Anuradhapura airfield was alright, the weather over China Bay was marginal. While it had stopped raining there were clouds over the airfield. Flying a light twin engined aircraft in bad weather, at night, was (and is) not a journey to be undertaken lightly. The pilots could not see any stars overhead. The weather en-route to Anuradhapura was unpredictable and could turn bad.

The pilots walked around and checked the aircraft (as per Air Force regulations), got into the cockpit and quickly did their preflight cockpit checks. In the meantime, the woman and child along with oxygen apparatus were wheeled up to the aircraft. The baby was continuously on oxygen. The base Doctor and the airman were also present. The Doctor himself had to travel with the patients as the condition of the patients was serious. A medical orderly would not suffice. The airman, the woman’s husband, was also accompanying the patients.

Prior to take-off, the Doctor had a discussion with the Captain. He requested the Captain not to fly too high as the baby would not be able to handle the lowering of air pressure. The maximum height the Doctor recommended was 2,000 feet. The Captain said that he would maintain 2,000 feet. The highest ground feature en-route to Anuradhapura was at around 1,000 feet in the Mihintale area. The pilots started up both engines of the aircraft, and quickly taxied onto the runway. The start-up was routine and both engines functioned normally. They did a standard take off, made a gentle turn and set course for Anuradhapura. The aircraft carried five adults comprising the two pilots, Doctor, the woman patient, the Airman, the baby and also oxygen equipment, and fuel for the journey. The Cessna was near its full capacity, although not overloaded.

The flight began normally. Nothing untoward showed on the cockpit instruments. Due to the darkness outside the Captain was flying mostly on instruments. The Captain continued to climb gradually. After sometime at a height of 1,500 feet the aircraft entered cloud. The Captain informed his co-pilot that he was switching over to complete instrument flying, and asked him to be alert and watch the instruments. Both pilots could not see anything outside as the thick cloud enveloped the aircraft completely. The passengers were informed to tighten their seat belts and get firm grips on handholds as the ride could get bumpy.

The Captain kept on climbing gently, flying through the cloud. When the aircraft reached 2000 feet he levelled off the aircraft, and kept flying at that height. He radioed China Bay and informed the tower that they were on a steady track to Anuradhapura at 2,000 feet. The ride was somewhat bumpy due to mild turbulence within the cloud. The aircraft droned on and soon they passed a point estimated by the pilots as being about one-third of the way to Anuradhapura. Suddenly the aircraft entered bad weather. The pilots judged it to be a moderate Cumulonimbus cloud. (Violent up or down drafts, and icing of the wings can occur in such clouds. It is not pleasant to fly though such clouds in light aircraft.) Immediately, there was severe turbulence and the aircraft began to bump up and down quite violently, and rain beat against the windshield of the Cessna. Both pilots concentrated on the cockpit instruments as the aircraft flew through the bad weather. The pilots had anticipated bad weather and

concentrated on flying the aircraft straight and level, on its track to Anuradhapura. They were fortunate that the bad weather was quite moderate in comparison to conditions which can sometimes occur in Cumulonimbus clouds.

The Rear Engine Malfunctions

After they had flown for about 5 minutes through the cloud, the Captain suddenly realised that his forward speed had begun to reduce. He felt a loss of power and quickly scanned through the engine gauges when he saw that the needles of all the rear engine’s gauges had begun to drop. A serious engine malfunction was indicated. The Captain then very quietly informed the co-pilot of the situation, as he did not want to alarm the passengers who were sitting just behind him in the small cockpit. The Captain did not use any gestures to indicate the problem, and also told the co-pilot not to show any alarm. The co-pilot responded calmly, and both pilots discussed the problem through the intercom system.

The Captain quickly moved the throttle forward but there was no response from the gauges nor did he feel any increase in power. The Captain quickly informed China Bay tower of the inflight emergency. The aircraft had now begun to lose height, and the Captain informed the co-pilot that they had to try and restart the engine. The two pilots quickly did the instrument checks which have to be done prior to an air-start, and then tried to start the rear engine. The Captain felt the engine being cranked by the starter motor, heard the ‘chunk, chunk’ cranking noise, but there was no ignition and the engine remained dead.

As they tried to restart the engine the instrument lights on the panel in front of them dimmed as a result of the sudden demand on the batteries. The pilots tried to restart the engine a second time, but again without any positive result. As the available electric energy was being depleted at each try, the Captain became worried about what would happen if, in addition to the problems they now faced, they lost battery power. Their situation could worsen. As they could not know the reason for the engine’s failure, their attempts to restart could, in any event, be futile efforts. They decided to try once more. This attempt too failed, and the Captain asked the co-pilot to feather the rear propeller.

They would now have to depend on the front engine alone. As the aircraft flew through the cloud, being thrown around by the turbulence, the Captain noticed from his instruments that the aircraft was losing height. He increased the remaining engine to full power. They continued to fly towards Anuradhapura, and in a little while they left the Cumulonimbus behind them, but were still enveloped by cloud. The front engine was at its maximum safe power setting, but the forward speed was too low to maintain a constant height. Slowly, but relentlessly, the aircraft kept on descending through the cloud. The Captain radioed both China Bay and Anuradhapura and informed them of the situation he was facing. He also reported that he could not pinpoint where he was, but that he was maintaining his navigational direction.

If the power of the front engine was further increased there was a very real possibility that the engine would malfunction. In which case there would be no option but to try and crash land in the dark; the chances of survival in such were minimal. Thinking of all these matters the captain decided to maintain the front engine at its maximum safe power setting, maintain whatever forward speed he could and allow the aircraft to gradually lose height This he did,

flying on instruments through the cloud. By this time the Captain estimated that they were more than halfway to Anuradhapura, but could not pinpoint their exact position.

The Captain had to decide whether to turn and head back to China Bay. He decided not to do so, as he would then have to fly through the bad whether again. The aircraft kept on descending through the night sky. The Captain now began to think of the hills in and around the Mihintale sacred area which rose to a height of around 1000 feet. The Captain did not wish to go below 1,000 feet, as there was a very real possibility of the aircraft crashing into these hills. On a normal trip aircraft never descended below 2000 feet, and would prefer to fly above 3000.

If the aircraft’s weight could be lessened its rate of descent could be reduced. The pilots discussed ways in which they could lighten the aircraft. The only possibility was to throw out the oxygen equipment, but if that were done the baby would surely die and the entire flight would have been pointless. The Captain also knew that none of the three adults in the back were conversant with aircraft. After opening the rear door and when throwing out some item they could damage a part of the wing or landing gear. So the Captain decided that nothing would be thrown out of the aircraft.

They kept flying through the cloud, and the aircraft kept on descending. The Captain was not sure of the exact distance which remained to Anuradhapura, although he had maintained his heading with the aircraft’s navigation instruments. After some time the cloud thinned-out and began to dissipate. The Captain asked the co-pilot to keep a sharp lookout for any familiar ground features. The Captain now thought that he would try to locate a paddy field or some other open space, and if necessary attempt a forced landing once he broke through the cloud.

The aircraft was now at a height of 900 feet. It had gradually lost 1,100 feet after the loss of the rear-engine. The Captain was acutely aware that the hills of Mihintale were in this area, and that the Cessna had dropped below 1,000 feet. The cloud finally dissipated altogether and then the Captain saw the lights of Mihintale temple area (this was a time when the lights in the temple area were kept burning throughout the night). On earlier journeys the Captain had seen these lights on many occasions, and he was able to instantly orient himself. Some of the ground features could be seen in the faint light.

The aircraft was now at a height of around 800 feet, and to his delight he saw that it was flying between two hills. In his estimation a mere 5-degrees in his heading, either to his right or left would have resulted in the aircraft hitting one of these hills. (Although he had maintained the correct navigational heading, the wind or bad weather could have pushed him off course). Soon they left Mihintale behind them, and flew on. He now realised that he was on a direct route to Anuradhapura.

The next problem was whether the aircraft would be able to reach the Anuradhapura runway, or, whether a forced landing would be necessary. Soon, in the distance, the pilots saw the lights of Anuradhapura town and were able to recognize the lights of the air base. But, maybe because he was at a much lower height than normal, the Captain could not recognize the runway or its exact alignment.

The normal practice on a night flight would be to fly over the runway at least once, orient oneself, and then land. Such a procedure was, of course, not possible on this flight. The only possibility was to carry out a very long ‘finals’ (i.e. the approach to a landing), try to maintain height, and then get the Cessna’s wheels onto the runway.

In the meantime the aircraft kept on descending. While maintaining their heading towards the air base both pilots kept a lookout for potential forced landing sights. The Captain could still not see the alignment of the runway. He informed Anuradhapura tower of this, and then an idea crossed his mind. He radioed the tower and requested that someone go to the end of the runway and fire flares along the runway. The path of the flares would, he hoped, enable him to align the aircraft for landing.

The Anuradhapura tower responded to his request very fast, and informed one of the fire vehicles which was already at the edge of the runway. It raced to the end of the runway and several flares were fired along its length. The Captain was able to see the flares and aligned himself with the runway.

Although the front engine was at full power, the aircraft kept on descending while drawing closer and closer to the airfield. The Captain kept the nose of the aircraft as high as possible, careful not to stall the aircraft, and kept the rate at which the aircraft was descending to its minimum. Talking among themselves, the pilots thought that the Cessna could crash some distance before the threshold of the runway. The aircraft, however, kept on drawing nearer to the airfield while steadily losing height. The height reduced from 150 feet to 75, to 60, 50, and so forth, and the co-pilot kept on calling out the height to the Captain through the intercom. Towards the very end the Cessna was at a mere 25 to 20 feet of height, and still the Captain was not sure whether it would be able to reach the beginning of the runway. There is some soft ground just before the Anuradhapura runway and the Captain decided that, if they could not reach the runway, they would at least crash land in that area.

Then, its engine a full power, the Cesena managed to struggle over the threshold of the runway and the Captain touched down gently on the tarmac. Both pilots heaved a sigh of relief. According to the Captain’s estimate if he had delayed more than 15 seconds, he would have had no option but to crash land on the perimeter of the runway.

As they rolled to a stop the emergency vehicles and ambulances rushed to meet them. The Commandant of No. 1 FTW (Flying Training Wing) informed the Captain that the ambulances were ready to take the patients. The Officers at Anuradhapura had planned for the contingency of the Cessna crashing prior to reaching the airfield, and teams had been prepared to rush to the crash site the moment information was received.

The mother and child were rushed to hospital, where they made a complete recovery. It was only after the landing the Captain informed the Doctor and the airman of the emergency that had occurred. The Doctor and airman were greatly surprised they had thought the flight had been a routine one, and that the aircraft had merely made a long descending approach to the airfield

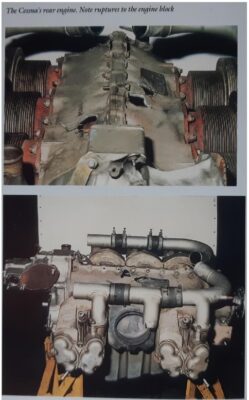

When the rear engine was inspected the next day it was found that one of the fuel lines coming to the manifold had ruptured Fuel was not getting to the engine, and therefore it was impossible to have restarted it in the air. The pilots remained at Anuradhapura for another four days while the Cessna was repaired. Once everything was in order and all the tests were complete, both pilots flew the Cessna back to China Bay. The then Commander of the Air Force Air Marsha A.W. Fernando, made a green endorsement in the Log Book of the Captain, commending him on his performance.

OPERATION EAGLE 1990

Extracted from “The Sri Lanka Air Force: A Historical Retrospect 1985 – 1997 (Vol. II)” by Jagath P Senaratne (with foreword by ACM Oliver Ranasinghe, Commander of the Air Force, 1994 to 1998)

The following is an account of Operation Eagle which was planned and executed entirely by the SLAF

When the LTTE reignited the separatist insurrection on 10 June 1990, they encircled and attacked many army camps in the North Fast. One of the camps which came under unrelenting attack was the Jaffna Fort within which the army had a significant number of personnel, along with police and some civilians. The LTTE entrenched itself around the Fort and kept it under constant attack with small arms, machine guns and mortars. The LTTE made several efforts to overwhelm the defenders with massed attacks by its cadres, but were beaten back by the defenders who occupied very good defensive positions behind the ramparts of the Fort.

Resupplying the Fort had to be done entirely by aircraft. Due to LTTE mortar and machine gun fire, helicopters could not land within or adjacent to the Fort as they normally did. From 10 June onwards food and ammunition had to be dropped into the Fort from Y-12 light transport aircraft and helicopters flying over the Fort, beyond the range of .50-inch calibre anti-aircraft machine guns used by the LTTE. By late June several personnel inside the Fort had become injured and there was an urgent requirement to land a helicopter in the vicinity of the Fort evacuate them to Palali.

Conference at AFHQ

In late June 1990 the Commander of the Air Force convened a conference at Air Force Headquarters in Colombo. The Chief of Staff, Director Operations, and senior helicopter and fixed-wing pilots were present. The subject of the meeting was to devise a plan to land a helicopter in or near the Jaffna Fort. In addition to several other LTTE positions in the area, the LTTE also had two heavy machine gun positions, one on each side of the Fort. It was decided at the outset that the helicopter would not try to land inside the Fort as, when it came over the ramparts, it would make an easy target. The helicopter could not approach from the North or South as that would entail flying over many LTTE gun positions. An approach from the East was also excluded as it would mean flying over many kilometers’ of built-up area where LTTE spotters would instantly give information of the helicopter’s passage. The only option was to come from the West, parallel to the Mandaitivu causeway, flying at very low level.

The next problem was where the helicopter would land. After a good deal of discussion, an officer walked up to the board and with the aid of a sketch map of the Fort showed how a safe landing spot was created by the structure of the Fort and the positioning of the LTTE’s guns. The LTTE’s heavy machine guns could not bring direct fire to bear upon this area, and therefore the helicopter would be reasonably safe while it was on the ground (which was also the time it was most vulnerable).

Another problem had to be dealt with. All flights taking off from Jaffna were being visually monitored by LTTEers on top of trees and buildings. They relayed the information by radio, giving the direction where the aircraft were heading. If a helicopter headed towards Jaffna City or Fort, LTTE anti-aircraft guns had time to get alert. Therefore, if the operation was to be done in daytime the helicopters would not take off from Palali. In the night they could operate from Palali as the spotters could not see the direction taken by the aircraft.

The First Attempt

In late June one helicopter, captained by Sqn Ldr C.R. Weerasinghe took off from Anuradhapura late in the evening. Coded messages had already been transmitted to Jaffna Fort. The helicopter approached from the west, flying low over the water, and stealthily approached the safe spot when the pilots saw two telephone poles and wires stretched across the proposed landing spot. These details could not be seen from aerial photographs. The pilot turned back and the mission was aborted. Later, in the middle of the night, some personnel came from the Fort and dismantled the wires.

Preparations for Operation Eagle

The objective of Operation Eagle was for one helicopter, the ‘Rescue Helicopter’, to land in the vicinity of Jaffna Fort, disembark some army personnel, ammunition and medicine, to take on board some urgent casualties from the Fort, and then to fly back to Palali. The helicopter had to be landed on the road which ran behind the Fort bordering the coast at that point. Simultaneously, other helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft would attack nearby LTTE gun positions.

Amidst tight secrecy a considerable amount of planning and preparations had to be done for this operation. The helicopter pilots who would do the actual landing in the ‘Rescue Helicopter’ had to be briefed, and had to do practice landings on the banks of a reservoir near Anuradhapura. This was done. The timings for the helicopter which went in for the landing, and the other aircraft which supported the operation had to be worked out. According to the plan Y-12s and SF-260 ground attack aircraft were to bomb and strafe specific targets just prior to the rescue helicopter going in, and while it was on its final run two more helicopters were to strafe targets on either side of the Fort. All these tasks had to be allocated and the pilots briefed.

On the evening of 2 July 1990 a SF-260 was sent to the Fort on a specific mission. Beneath its wings were two bomb casings within which were copies of those parts of the plan which pertained to actions by personnel inside the Fort (i.e. the specific timings and tasks which they had to execute. This could not be communicated even by coded radio as that it may have alerted the LTTE). The pilot’s mission was to dive and drop these bomb casings within the walls of the Fort. He did so successfully and came back to Anuradhapura. In the meantime, at 6000 feet over Jaffna Fort, the mission leader of the operation did a simulated run of the rescue helicopter’s flight, dropping in height and simulating a wave-top level run parallel to the Mandaitivu causeway. With this dummy run, far above the LTTE’s antiaircraft guns which were firing at them from below, the precise horizontal timings were noted down and the actual operation was carried out accordingly.

The Operation Begins

As per the plan, the mission leader and two helicopter gunships left Palali at 04:00 hrs on 3 July 1990. The mission leader went to the operational area while the two gunships maintained a holding pattern over a pre-planned location. Many other aircraft had already arrived. The Y-12s and SF-260s which had come were in holding patterns over the sea. They would attack pre allocated targets at coded instructions from the mission leader. One of the tasks of the Command helicopter was to ensure that all these aircraft were at their pre allocated heights and that they maintained these vertical separations (this was to preclude any mid-air collisions of these aircraft which were flying around in the area, in the dark. The aircraft were of course not showing any lights).

In the meantime the Captain and co-pilot of the Rescue Helicopter, both of whom were very experienced SLAF helicopter pilots with many thousands of flying hours. Sqn. Ldr. L. Waidyaratne and Fg Off A.P Mirando, had woken at 03:30 hrs. They had some tea and began to prepare themselves the flight. They had much on their minds and had not slept well. The night before they had checked and double checked the helicopter they would fly on the mission. On the previous evening they had flown from Anuradhapura in Bell-412 serial number CH-523, in which they were do the operation (this was the same helicopter hit by an unarmed RPG round in 1986). After landing at Palali a small defect was found in this helicopter: Immediately another helicopter which was on stand-by was made available to the pilots (anticipating such problems was a part of the meticulous planning which went into this operation). The new helicopter was also a Bell-412, serial number CH-524. The pilots checked out the helicopter thoroughly and found it was fully serviceable.

Meanwhile, the mission leader had arrived over the sea in the Mandaitivu/Jaffna Fort area. Complete radio silence was maintained by all aircraft in the operational area, except for terse coded instructions which constituted of single words (for example, the sign for the Rescue Helicopter to begin its run to the Fort was ‘Maradonna’). As the Command helicopter circled the area, the mission leader and its other personnel noticed that in addition to the darkness which enveloped the area, the entire Mandaitivu and Jaffna Fort area had a low cloud base with a considerable amount of patchy clouds, and there was ground mist. Visibility was not good enough for ground-attack by fixed-wing aircraft. The mission leader decided not to call upon the fixed-wing aircraft to bomb and strafe the LTTE positions in the vicinity of the Fort, as originally planned. At 05:05hrs, the Rescue Helicopter arrived at its pre-allocated position and reported to the mission leader. The two helicopter gunships too were in position. Then, after assessing the situation for a few minutes and checking that every aircraft was in its pre-planned position, at 05:15 hrs the mission leader called out “Maradonna, Maradonna” on the radio. Immediately, the Rescue Helicopter, several kilometers away, began its run to the Fort.

The Flight of the Rescue Helicopter, CH-524

The Rescue Helicopter, CH 524, lifted-off at 04:50 hours from Palali airfield. In it were the two pilots, two door gunners, and four army personnel (one officer and three other ranks) and a conment of medicine, food, weapons and ammunition. Therefore, a total of eight persons were on board. This was not a heavy load for a Bell-412. As intended, the planners did not want the helicopter to be even near its maximum payload as that would have made the aircraft less manoeuvrable.

The helicopter climbed to 2,000 feet over Palali and flew westward till the pilots saw the Karainagar Navy camp’s security lights below them, and then flew toward Mandaitivu Island. While doing so, as planned, the pilots began gradually descending to 1,000 feet. The aircraft arrived at its pre-allocated position near Mandaitivu and reported to the mission leader at 0505 hrs. It then circled and waited. And waited. As usual, the waiting just prior to the operation was somewhat difficult to get through. The pilots spoke to each other and the two gunners over the intercom. The atmosphere in the cabin, filled with the whine of the 412’s twin turbine engines and the noise from the four rotor blades, was tense. The door gunners checked their machines and kept a close watch. They were und strict orders not to fire until ordered by the Captain.

Then, at 05:15 hrs the rescue helicopter pilots heard the words “Maradonna Maradonna” over their radio. They immediately set course towards the Fort, whist descending rapidly. In a few moments they were at a height of 50 feet above Mandaitivu lagoon, flying at a speed of 80 knots, headed in the direction of the Fort. They flew parallel to the Mandaitivu causeway which was on their left, a useful visual cue, faintly visible in the dark.

Simultaneous with the rescue helicopter’s descent, the two helicopter gunships swung into action and attacked pre-located LTTE positions on either side of the Fort. They laid down a withering hail of gunfire and rockets. Each of the gunships was heavily armed. As the range from Palali was minimal they carried a comparatively low fuel load but heavy armament and ammunition. Each was configured with one rocket pod with 7 rockets and one forward firing

.50-inch calibre heavy machine gun with 250 rounds of ammunition, both of which could be operated by the pilots. In addition there was a machine gun mounted in the doorway on either side, one of which was a .50-inch calibre heavy machine gun with 1,000 rounds of ammunition, and the other was a 7.62mm calibre machine gun with 1,000 rounds of ammunition. Both gunships fiercely attacked the LTTE positions on each side of the Fort, and the LTTEers in the bunkers were compelled to keep their heads down (the gunship pilots knew that it was their task to distract the LTTEers and force them to keep their heads down as otherwise the danger to the rescue helicopter would increase considerably). Some LTTEers fired back at the gunships but the helicopters suffered no hits

In the meantime the rescue helicopter kept on flying towards the Fort but the LTTEers, distracted by the gunships, were quite unaware of it. The Rescue Helicopter was now more than halfway to the Fort and still not a single shot had been fired at it. Its pilots could see the tracer rounds and rockets fired by the gunships registering on targets on the ground, and they could also see gunfire directed at the gunships from the ground. But no fire was aimed in their direction. As the Rescue Helicopter flew in the direction of the Fort the pilots suddenly began to see the faint shape of some buildings directly in line with them. They then realised that these were the former police quarters, now occupied by LTTE gunners, which were on the right-hand side of the Fort. They realised that the helicopter was slightly off course. The pilots then initiated a gentle turn to the left, bringing the helicopter in-line with their intended landing spot just south of the Fort, outside its walls. By this time the pilots had begun to reduce speed and the helicopter was now flying at about 60 knots. As the Rescue Helicopter came close to the shore some LTTE gunners became aware of its existence, and began to fire at it. There were no hits on the helicopter. The door gunners did not fire as their muzzle flashes, in the pre-dawn darkness, would have indicated the helicopter’s position to the LTTE gunners. As the helicopter crossed the shore line and approached the landing area the pilots suddenly saw a telephone pole some distance in front of them. The Captain quickly pulled back on the control column and climbed just a little, cleared the pole, and sank back again to their former low height of about 15 feet.

Soon afterwards the Rescue Helicopter arrived at the landing spot, and, as planned, while descending the last few feet, executed a very quick and smooth 180-degree turn so that the aircraft was facing the direction from which it had come, out to sea (this was the specific landing pattern which they had practiced on the bund of a reservoir in Anuradhapura, the previous day). As the helicopter landed some LTTE gunners began to fire in their direction. The gunships in the dark sky above kept up their barrage. When the helicopter was on the ground the LTTE gunners could not fire directly at it. Mortars were a possibility but none were fired. As the helicopter landed personnel from the Fort appeared out of the dark with the serious casualties, and simultaneously the four soldiers, ammunition and medicines were quickly off-loaded, each soldier grabbing his allotted load. Soon after the casualties were loaded into the helicopter. The entire process of unloading and loading lasted approximately 40 to 45 seconds. During this time the LTTE intensified its fire and used various types of weapons. Towards the latter stage some mortars were fired but none landed in the landing area. The Rescue Helicopter suffered no hits.

When the gunners reported to the pilots that all the casualties were in the cabin, the Captain immediately lifted-off and flew very low and fast out to sea. The LTTE kept on firing, and some specially dangerous heavy machine gunfire came from the starboard quarter. The starboard gunner, after gaining permission from the Captain, fired at these muzzle flashes as the helicopter rushed away. The helicopter kept on flying very low over the water for about 2 minutes till out of range from the gunfire and then pulled up and climbed to 2,000 feet and headed back to Palali. CH-524 landed at Palali at 0535 hrs with seven casualties on board, two of whom were Airmen. Ammunition expended was 105 rounds of 7.62mm machine gun ammunition. Damageto aircraft: Nil. Very soon all the other helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft landed and as the tension leaked away there was a great deal of congratulatory back-slapping and good humour. All the pilots, gunners, and other staff went to the messes for a hearty breakfast. The mission was accomplished as planned.

(Note: One of the gunships was captained by Fg Off T.C. Kaluarachchi and his co-pilot was Plt Off

E.A.D. Edirisinghe. Kaluarachchi was killed-in-action on 10 November 1997 while flying in a Mi- 24 attack helicopter, and Edirisinghe died on 25 November 1997 in a crash on a night CASEVAC mission in the Puliyankulam area. The other gunship was captained by Sqn Ldr C.R. Weerasinghe who died in the BAe-748 (Avro’) crash at Palali on 28 April 1995.)

Operation Eagle-2

On 29 August 1990, at 1615 hours, a single Bell-212 flew another CASEVAC mission to the Jaffna Fort. This helicopter was captained by Fg Off T.C. Kaluarachchi. Artillery and mortar fire from the army positions in Mandaitivu Island first softened up the area around the Fort from 1515 hours, and compelled the LTTE to temporarily withdraw from the area. The mission was executed as planned and the Bell-212 dropped some urgently needed medicine and food and evacuated some urgent casualties. Further, some urgently required 120mm mortar ammunition was also delivered to the Fort.

***************

SLAF ASSISTANCE DURING THE ATTACK AGAINST SILAVATTURAI CAMP

1991

Extracted from “The Sri Lanka Air Force: A Historical Retrospect 1985 – 1997 (Vol. II)” by Jagath P Senaratne (with foreword by ACM Oliver Ranasinghe, Commander of the Air Force, 1994 to 1998)

On the night of 19 March 1991 the LTTE attacked the Silavatturai army camp, a somewhat lightly defended camp very near the beach on the coast south of Mannar. They first surrounded the camp from the South, East and the North and attacked from the North using RPGs and .50-inch calibre machine guns while taking cover behind the buildings of the town. On the first assault the LTTE captured the Eastern side of the camp. The camp had a strength of approximately 150 army personnel. The LTTE’s attacks were kept at bay till 22 March by the unrelenting Close Air Support and battlefield interdiction missions which were flown by the SLAF. By 22 March the LTTE gave up the attack, having lost hundreds of cadres to SLAF fire.

Due to the location of the camp, and the possibility of LTTE counterattacks, no army reinforcements were sent immediately. The burden of assisting the camp had to be borne entirely by the SLAF. As soon as the news of the attack was received, the SLAF bases in Anuradhapura and Vavuniya became activated. Pilots flew non-stop CAS shuttles to and from Silavatturai. As one aircraft finished its attack it would exit the area and fly back to base to refuel and re-arm. In the meantime, another aircraft would descend from those circling above and attack LTTE positions. Then it would exit the area and get back to base.

In the meantime helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft which had refueled would head back to Silavatturai. In this way at least one helicopter or fixed-wing aircraft was always over the camp at any one time, day and night.

Air support was called for at 1845 hrs; consequently aircraft had to fly CAS missions throughout the night. This was the first major air operation undertaken in total darkness. The camp was illuminated by one small kerosene lamp in a pit which was barely visible from the air. Pilots also used LTTE muzzle-flashes to orient themselves.