The Sigiriya Frescoes and Their Maidens: The Hard Work of Restoration

Source:Thuppahis

From Raja de Silva’S book Sigiriya — as excerpted in the Island, 18 April 2021, with the title “Dangerous and meticulous work copying Sigiriya frescoes in Bell era (1896)

The village of Sigiriya is mentioned in the 16th century book of Sinhala verse titled Mandarampura-puvata. From then on, the site seems to have disappeared from the public record until its rediscovery in the 19th century. Major Forbes of the 78th Highlanders and two companions rode from Polonnaruva through Minneriya and Peikkulam in search of Sigiriya, and reached the site early in the morning of a day in April 1831 (Forbes 1841).

They returned to the site two years later and Forbes explored further the cavernous walled gallery on the western side of the great rock, which led towards the summit. Forbes was surprised to observe a durable plaster on the brickwork of the wall, while above the gallery, especially in places protected from the elements, the plaster was seen to be painted over in bright colours. However, he was disappointed and puzzled in not recognizing any representations of the lion, which, according to local lore, gave the name of Sigiri, i.e., Sinhagiri to the rock.

The lion that eluded Forbes was tracked down by the next visitor, who remained anonymous in recording his impressions in 1851 under the title “From the notebook of a traveller” in a magazine known as Young Ceylon. This early visitor described the gallery as a long cavernous fissure, the outer edges of which were deeply grooved and a brick wall raised there, nearly to the roof. The inner surface of the “cave” was described as “covered with a coating of white and polished chunam gleaming as if it were a month old”.

Some of the plaster from the ceiling and the rock side of the gallery had fallen off, but it was noted by the visitor that “there was a profusion of paintings, chiefly of lions, which is said to have given the name of Singaghery, Sihagiri or Seegiry to the ancient site”. No other visitor had reported on these lions.

Twenty four years later, Sigiriya and the paintings were brought to public notice by TW Rhys Davids (1875), formerly of the Ceylon Civil Service, in a lecture given before the Royal Asiatic Society, London. Rhys Davids described his observation, through a telescope, of the “hollow” halfway up the western side of the rock, with its surface covered with a fine hard “chunam” plaster on which were painted figures. He mentioned that the northern (i.e., further) area of the gallery was covered with ornamental paintings (again, to be lost not long after) and thought that a large number of these may have been erased with the passage of time. By the close of the century, when the Archaeological Survey Department (ASD) commenced work at Sigiriya, these paintings had all disappeared.

TH Blakesley (1976) Public Works Department, viewed the paintings from afar in 1875, and reported for the first time on their subject, which he recognized to be female figures “repeated again and again”, showing only the upper parts of their bodies, and richly ornamented with jewellery. The figures (he said) had a Mongolian cast of features. Blakesley also examined the plaster layer adhering to the accessible parts of the main rock, and remarked on the existence of paddy husks in the ground.

Reports of the existence of paintings at Sigiriya had attracted the attention of connoisseurs of art in Sri Lanka and in England, and Sir William Gregory, the former Governor, requested Alick Murray (1891), Provincial Engineer, to attempt to reach the paintings and make reproductions of them. This proposal was sanctioned by Sir Arthur Gordon, the Governor, who gave every encouragement to the project. Murray went to Sigiriya, fired with enthusiasm for this pioneering venture, but was disappointed to discover that the local villagers would have no part of his plans for disturbing the rock chamber which, they imagined, was inhabited by demons. The populace, however, was, persuaded to clear the jungle at the base of the rock in the required direction, while Murray awaited the arrival of Tamil labourers who were urgently requested from South India.

The Tamil stonecutters (who had no fear of Sinhala demons) bored holes in the rock face, one above the other, into which were fixed with cement, iron jumpers. As they went higher up the rock towards the cavern containing the paintings, the man of the lightest weight had to be selected to bore the holes. After a while, even this labourer found it difficult to ascend higher. He supplicated that if he were allowed three days of fasting and prayer, he might succeed in finishing the task. Murray answered his prayer in the affirmative, thinking that it might lighten the man’s weight and thereby help him to reach the pocket containing the paintings. Once this goal was reached, it was found that the rock floor was at too steep an angle to permit one to stand or even sit on it. A strong trestle or framework of sticks was made and secured to iron stanchions let into the rock floor. A platform was made and placed on the framework to enable one to lie on his back and view the paintings.

On June 18, 1889, Murray made his historic climb into the fresco pocket, and he worked for a whole week lying on his back on makeshift scaffolding to make tracings of six paintings in coloured chalk on tissue paper. The work was done, climbing up and down each day, (as he said) “from sunrise to sunset”, the only inmates of the cavern being swallows who used to “peck at him resentfully”. When his work was reaching conclusion, a few of his friends including SM Burrows, Government Agent, Matale, hazarded the climb to the pocket to visit him, and it was suggested that a memento be left behind. A bottle was obtained and in it were deposited a newspaper of the day, a few coins, and a list of names of friends who had visited him at work. Murray’s party was astonished when a Buddhist monk and a Saivite priest sought permission to enter the chamber, and they were accommodated by Murray. They prayed for the preservation of the bottle, thereby adding solemnity to the occasion of its sealing into the floor with cement – a ceremony that was accompanied by Murray and Burrows singing “God Save the Queen”.

An unfortunate result of Murray’s excellent efforts at tracing the paintings under the windiest of conditions was that, on detaching the tracing papers that had been pasted with gum on the periphery of each figure, an egg-shell thin layer of painted plaster (i.e., the intonaco) also came away revealing a white framework of the layer of ground underneath. Another deplorable result was that a few Tamil labourers had scribbled their names on the painted plaster. The copies made by Murray were stated by Bell to have been exhibited above the staircase of the Colombo Museum.

Murray described the paintings as having been done on the roof and upper sections of the sides of the chamber; that they represent 15 female figures in all, but no doubt many more had existed originally, as traces of them were to be seen. The freshness of the colours (he observed) was wonderful, curiously, green predominating. Each figure was stated to have been life-size and many were naked to the waist, the rest of the form being hidden by representations of clouds. They were arranged either singly or in sets of two, each couple representing (he said) a mistress and a maid.

Access to Fresco Pockets

In 1896, Bell made regular access to the fresco pockets possible by the construction of a vertical ladder of jungle timber from the gallery to the cemented floor that was spread on the sloping -round of the rock cavern 40′ above. The shorter and narrower pocket A was made accessible from pocket B by a floor of iron planks set on iron rods as supports let into the surface of the rock horizontally and grouted in.

The early timber ladder was replaced by an iron wire vertical ladder with safety measures of hoops of cane and wire netting around it in 1896. A spiral staircase of iron steps was constructed in 1938. Another similar staircase was recently constructed by the Central Cultural Fund (CCF) cheek-by-jowl with the earlier construction and is used as the method of access to the fresco pocket at a point to the south of the original doorway. Visitors now use the old stairway as the exit from the pocket.

Eighty-five years ago entry to the fresco pockets was restricted to those who had obtained permits from the Archaeological Commissioner. (AC).

The public has the opportunity of taking their cameras into the fresco pockets, on permits issued by the ASD, and photographing the paintings. No persons are allowed to have their photographs taken in front of the paintings, and at least two guards are stationed inside the fresco pockets as a security measure. No electronic or other flashlights are permitted in photographing the paintings.

Documentation and Copying of the Paintings

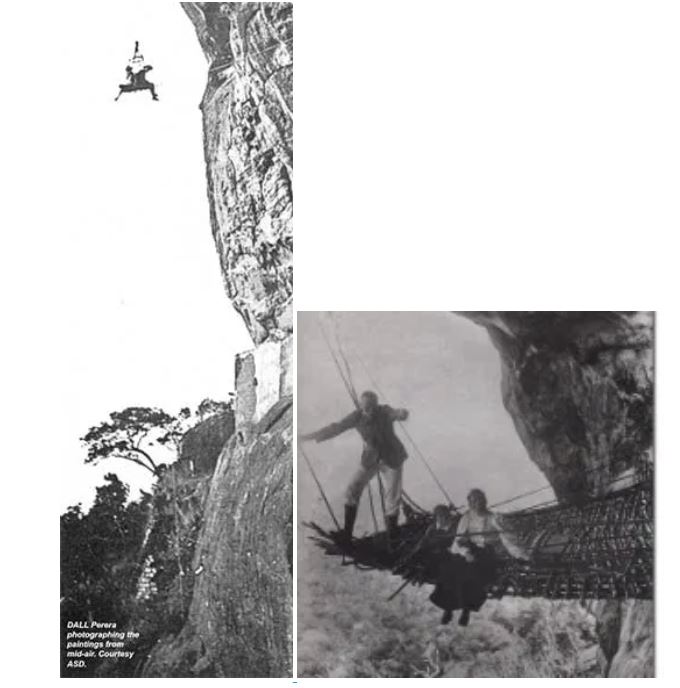

Bell decided to photograph the pockets from a distance at the same elevation, and record the disposition of the paintings within. For this purpose a four inch hawser was let down from the summit to the ground with an iron block tied to the end. Through the block a two inch rope was passed and an improvised chair firmly tied to it, whereon the photographer took his seat. The hawser was then hauled up from the summit, 150 feet up until the chair was level with the pocket and 50 feet clear of the cliff, but due to the force of the wind that caused it to sway in the air, the photographs taken were not clear.

It took DAL Perera, Chief Draughtsman and Bell’s “Native Assistant”, a week to do an oil painting to scale, while perilously suspended in mid-air like the man on the flying trapeze. The painting was later photographed and lithographed to make a plate. From the top of the iron ladder the rock curved inwards for four feet or so to an upward rising floor of pocket B where it was not possible to safely stand or even sit on the smooth surface. As a safeguard at the head of the ladder and along the entire edge of both pockets B and A to the north of it and the ledge between them, iron standards three foot three inches in height, with a single top rail, were driven into the rock Bell stated: “Without such a handrail, a slip on the smooth inclined floor of the pocket would have meant instant death on the rocks fifty yards below.”

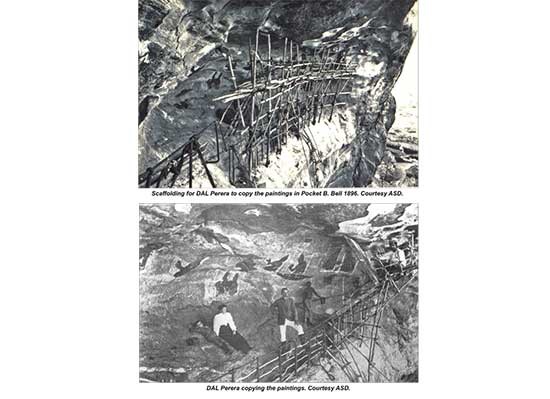

In the last week of March 1896, Perera made copies of six paintings in pocket B while being dangerously seated on the sloping floor. In the following year with additional safeguards and working platforms, Perera continued copying the remaining paintings in the two pockets. Bell reported that 13 of the paintings in pocket B could be easily reached from the floor, being painted on the rock wall and the lower part of the oblique roof of the cave, but they were not at one level. It was these paintings that Perera copied in 1896 and 1897 while being uncomfortably perched on the sloping floor of the fresco pocket, which had in 1897 been cemented towards the outer edge.

The painting at the extreme south, i.e., No. 14 and the fragments No. 15, 16, 17, were out of reach and well up on the roof of the pocket. To get at these paintings, it was necessary to construct a “cantilever” of jungle timber, firmly lashed to a stout iron cramp let into the rock floor. To the end of this projection was tied a rough “cage” of sticks, from which uncomfortable and perilous perch Perera made copies of the last and highest figures in pocket B.

It was even more difficult and dangerous to fix a hurdle platform outside the narrow and slippery ledge separating pocket B from pocket A and onwards to the end of this pocket. It took 10 days to construct this stick-shelf (massa). In addition to P iron bars supporting the woodwork, the whole braced strongly to thick iron cramped into the rock, the platform had to be further held up by a central hawser and side ropes, hauled taut round trees on the summit 300 feet up. When finished this improvised platform stood out 15 feet from the cliff.

It took Perera 19 weeks to complete copying the 22 paintings – 5 in pocket A and 17 in pocket B.

The constructional details and measurements given above are intended to serve several purposes: to enable the reader to appreciate the labour and expertise in 1896 exercised by the authorities in setting up the elaborate apparatus for Perera to copy and photograph the paintings – all for the love of preserving our ancient artwork; to appreciate the great care taken by Perera under perilous conditions to make such excellent copies of 22 paintings, now exhibited in the Colombo Museum, which Bell extolled in superlative terms:

“It is hardly going too far to assert that the copies represent the original frescoes as they may still be seen at Sigiriya, with a faithfulness almost perfect. Not a line, not a flaw or abrasion, not a shade of colour, but has been reproduced with the minutest accuracy”. (Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Ceylon Branch (1897).

The details and measurements are also intended to impress upon readers the magnitude of the feats of our craftsman in ancient times, who constructed broad, long scaffoldings rising to a height of around 400 feet using jungle timber and creepers; and to marvel that the artists painted their subject so well, during a very long period upon multi-layered plaster on the wind-blown exposed rock.