The Bibiles of Bibile: A Sinhalese-Wedda Aristocratic Family – Ranil Bibile

RACIAL HISTORY OF A SINHALESE-WEDDA ARISTOCRATIC FAMILY

From the papers of

Baron Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt

Who visited Ceylon, Bibile, and the Bibile Walauwa in 1927 And obtained the family history from

The Rate Mahattaya of Welassa

Charles William Bibile

English Translation of Bibile materials (Eickstedt)1:

„Rassengeschichte einer singhalesisch- weddaischen

Adelsfamilie“

von Dr. Egon Frhrn. v. Eickstedt, München

(Aus den Ergebnissen der Indien‐Expedi on des Staatlichen

Forschungsins tuts für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig)

English Translation of Bibile materials (Eickstedt)1:

„Rassengeschichte einer singhalesisch- weddaischen Adelsfamilie“ von Dr. Egon Frhrn. v. Eickstedt, München

(Aus den Ergebnissen der Indien-Expedition des Staatlichen Forschungsinstituts für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig)

Racial history of a Sinhalese-Wedda Aristocratic Family

If two populations live close to or even mix up with each other for a longer period of time, mixed marriages are inevitable to occur, and this, necessarily, had also a considerable impact on the cultural expressions of the resp. more civilized nation. Soaking up the mentality of another people leads to a reshuffling and tensions within one´s own nature. This might be particularly the case if there is a considerable distance between the two populations in terms of their cultural habitus and also, in case the more primitive gets the opportunity to infiltrate the higher levels of the more cultured people. Examples from the history of great nations like Romans, Arabs or medieval Portuguese show that such racially determined biological impacts on the cultural history of certain nations and social strata are not as rare as one might possibly expect, considering the extrinsic similarity of the respective cultural complexes.

Particularly interesting, but much lesser known is it, that these phenomena can also be found in India – the country of allegedly rather rigid caste systems. The severe caste mentality of the Indian conqueror people knew numerous exceptions, and these have strongly influenced the biological consequences of social seclusion. Within the whole large complex of territories occupied by Indian monarchies, the relationships between the Aryan or Dravidian master peoples and the oldest, i.e. the Weddoid strata of society are exempted – in surprising like mindedness – from the customary integration into caste hierarchies. The most ancient lords of the land were somehow standing outside the caste system and not regarded as impure by the higher castes of the conquerors. This created the possibility for blood of the always very primitive aborigines to seep in – a possibility made much more difficult for the low castes of their own civilized population.

Reliable evidence for such blending processes between primitive and culture people which could certainly find the interest of racial as well as cultural science is currently almost absent from literature . Each and every such case, due to the differences in somatic and psychological

disposition of both components, would needs have to be examined and judged separately. Thus, a vast and productive field for racial studies opens here.The following modest notes will select only a few single cases from the author´s most familiar field of work. However, these modest notes have one big advantage: the genealogical and historical source material on which they are based are well guaranteed – a rather large part of them has been made available to me due to the kind interest of my friend C. W. Bibile, Rátemahátmaya of Welasse, and I would like to use this opportunity to once more express my gratitude for his interest and cooperation. Due to the special nature of the material it became necessary to check it on the spot, that is why I spent my few days of rest after an exhausting crossing of the jungle woods of East Ceylon with writing down of these data.

Among the distinguished Sinhalese families of the Uva district ( Eastern Ceylon) with their extreme proudness of tradition who for many centuries have served the oldest dynasty of the world, several are boasting of a direct descendence from the old aborigines, the Wedda. The rigid and arrogant caste spirit of the old Sinhalese élites just in Kandy (the Ceylonese highland, independent till 1815), who didn´t even regard the inhabitants of the western lowlands with its European colonies completely as their equals, indeed treated the Weddan blood in former times as coequal. In our times, however, this is true of the old Kandyan families in certain limits only, and it is even less true of the nobility in the Western lowlands. These nowadays regard the Weddas as not more than a last heap of miserable “savages” on the verge of dying out. Yet in the Eastern parts of the island, the esteem for the Weddas is still directly showing up in common behaviour: the district chief, clad in silken sarong, has to receive orders in standing while the dirty and almost naked Wedda is asked to squat down. “The Weddas are of high caste.” This behaviour is due to the far-reaching independence that even now is, or has to be, admitted to the few surviving Wedda families, and it is also due to their former position at the court and in the army of Sinhalese kings. This early influence of the Wedda chiefs was based on the great, and often deciding, importance the Wedda troups had for the power and existence of the Sinhalese kingdom as the following family histories amply show.

Even in th early years of the rule of King Rajasimha I. (1571-1592) the later 18 Wedda districts of Ruhúna – today´s Ùva- and Batticalóa district – were independent from Kandy, while the northern Wedda districts had already for a long time been under nominal Kandyan rule. The occupation of the country by Rajasinha led some dissatisfied chiefs to emigrate. According to a

reliable tradition written down in document form already at the time of his grandson, M á h a K á i r a W á n n i y a of Moráne Wátta1 was also among these dissatisfied persons. He had a kind of permanent residence at the foot of the Moráne mountains in Binténne, the remnants of which are shown even today,. After a long stay in Damánegama, in the far North-East of today´s Nilgála Kórale, he left his eldest childless son there and with his second son K u m á r a W á n n i y a of Welássa 2 returned to the area of today´s Bibile. There must have happened a complete reconciliation between king and Wedda prince, because soon after, the names of both sons are found among the names of guardians of the royal treasure. P i e r i s, in his voluminous history of the Portuguese Era in Ceylon 3, relying on the original old Sinhalese source Parángi Hátane, describes the Wedda as in the following way:

“ And yet these backward people….. were among the most faithful servants of the King´s treasures, twelve of them being chosen to be the custodians and invested with silver girdles and canes embossed with silver, and a special dress to distinguish them from their fellows. They would stealthily enter the palace at night and interview the King when they desired orders on any matter affecting their charge.”

From this report the great independence on the one side, and on the other the eminent trust in the Weddas who even today are regarded as reliable is clearly evident. The same can also be inferred from another tradition, describing the immediately following unfortunate historical period of the Sinhalese rule:

” When pressed hard by the invasions of the Portuguese which were soon to follow, it was to them that the King used to entrust the Queens, and they would shelter them in temporary huts, brightly adorned with greenery according to Sinhalese custom, constructed in dense forest which stretched for fifty miles between Welásse and the first range of Batticalóa hills, a region into which the Portuguese never succeeded in penetrating.”4

1 M á h a means „the Great, the Elder”; K á i r a is even now a widely met Wedda name; W á n n i y a is the medieval term for chief and up to this day in favourite use as title, and M o r á n e is the name of the most distinguished Wedda clan.

2 Welássa means „land of the thousand stripes of ricefields“, a very ancient name pointing to former wealth and it is used even today to denominate the district of the Rátemahátmaya of Bibile, although for already thousand years the land is covered by dense forest jungle.

3 P i e r i s: Ceylon, the Portuguese Era….. 1505.1558. Vol.I, Colombo 1913, 327

4 Cf. P i e r i s , op. cit. I, 329

In times of emergency the Wedda land had been the last resort of Sinhalese kings. When after countless atrocities Kandy, too, fell into the hands of the Portuguese, the king was forced to flee:

“ But with his family, his juwels of gold and his gems, his slaves

and records and his treasure chests,

K i n g S e n e r a t s o u g h t r e f u g e i n t h e P a t t u o f t h e W e d d a h s, for his glory was dimmed and his merit had failed.

And the heart of the man melted as wax before the flame of the fierce Parangi foe.”5

Kumára Wánniya, the younger son of the Wedda chief Máha Káira Wánniya of Moráne who had gone to Bibile, got married to the daughter of another Wedda chief, whose name is not known. Under the command of different Sinhalese kings his two sons participated in several campaigns against the Portuguese and later on against the Dutch and were awarded the title

and office of a Mudiyánse 6

by king Sénerat ( 1604-1632, see above). At the same time, both

brothers were simultaneously, i.e. on legal grounds at first the elder, J a y a s ú n d a r a M u d i y á n s e (see family tree), entrusted with the hereditary fiefdom of the villages Bibile and Alanmulla, and a royal document was issued to confirm it.

This royal document, written by steelpen on strips of prepared Tálipot leaves, is today preserved in the archive of the British Registry in Badulla under Nr.5, a reprint being in possesion of the author. Even nowadays the village Bibile belongs to the progeny of the old Wedda prince and the lines of this note are written in the Waláue (aristocratic residence) of his great-grandson in Bibile.

The following details, being of interest for the racial history from the early period of the Bibile family, may be given here. In the Arangá Palace in Wegáma, “where the daughter of the Batticalóa Wánniya was the Queen of the King” (evidently, the king had different wives in his different palaces), a Bibile and a Kaudélle Mudiyánse had the command over the royal guards (again a typical Wedda office!). From this report we also see that the wife of the king (we are

5 Párangi Hátane: cited after P i e r i s, op. cit. I, 417. Párangi = Portuguese.

6 In peace times, the Mudiyánse were higher officers of the palace guards, while in war times they were charged with deploying the people of their fiefdom capable of bearing arms and with marching against the enemy in lead of them. This is, so to speak, a typical Wedda office, but clad in a high position, connected with dignity and fiefdom, both usually granted to especially excellent, but mostly Sinhalese nobles only.

talking about Wimalla Dhárma Súriya I., 1592- 1604, the 172nd ruler of the Sinhalese) had been the daughter of a Wedda prince, i.e. the Wánniya of Batticalóa, and that, consequently, also Wedda blood rose up into the royal family.7 The Sinhalese chronicle further states that during the reign of King Sénerat (see above), when he resided in Mayangáne, a Bibile Mudiyánse was appointed as one of the guards for the young prince Tíkiri Bándara (the later king Rajasinha II., 1632 – 1684). When he himself (i.e. Rajasinha II, M.S.) during his reign recaptured the fort of Batticalóa from the Portuguese, a Bibile Mudiyánse who had excelled in battle was endowed with two Portuguese as his slaves – a fact that is also not without interest in terms of racial science. Furthermore, to the great favour that just the Bibile Weddas enjoyed at the royal court can the fact be traced back, that it had been the daughter of an Urulewátte Adigar – i.e. of a senior minister from an ancient Kandyan family – who, on royal command, had been married to the Jayasúndara Mudiyánse of Bibile. In any case, the reliable and influential Wedda prince, himself belonging to the most distinguished – the “royal”- Wedda clan, should in this way be bound more closely to the throne. With the same purpose in mind, he might have given his sister into marriage to the court noble Pubbáre Bándara.

Anthropologically speaking, these marriages are important because they vouch for when and how noble Sinhalese blood got into the purely old-Weddid Jayasúndara and, vice versa, Wedda blood was received into the Sinhalese noble family of the Pubbáre Bándara. Thus, the descendants of both families were both half Weddoid, half Sinhalese and, biologically speaking, both descendants of Máha Káira Wánniya. This is important because with the childless grandchildren of Jayasúndara, the first male line dies out, and Pubbáre Bándara Káragahawela (also a grandson of Jayasúndara) who by cousin marriage (through which no fresh blood from any side comes into the family) continued the old family tree, biologically as well as legally, by adopting these three childless grandchildren (see family tree).

Thus, this old Wedda family had preserved its purity for three generations and in the fourth to fifth generation had become half Sinhalese. In the seventh generation the male line again extinguished, but was continued biologically and legally by cousin marriage of Lóku Ménika with Kaháttam Hínbanda. Because the husband went over to settle in the house of his wife, this

7 This was by no means the first time. Already Wijéya, the banished viceroy of Gujerat in Northern India, who later became the first Sinhalese king (543-505 B.C.), had married a Wedda princess. Her and her children´s unfortunate fate has been recorded in the Great Chronicle of Ceylon”(cf. W. G e i g e r, The Mahavamsa, London 1912, Chapter VII, pp. 55-61) and is mentioned also in most of the popular history books on Ceylon.

marriage was called Bínna-Ehe. Then,in the sixth till eighth generation only Sinhalese names are found among the married-into families. But because almost exclusively all these families belong to the old nobility of Eastern Ceylon it seems quite unlikely that they should n o t contain Wedda blood. It merely can´t be made out to what degree this was the case.

Since the last century, that has seen the final decline of the Wedda people and at the same time the downfall of the old kingdom of Kandy (probably not coincidentally), among the higher families such kind of intermingling with the Weddas seems to have ceased. More and more – with continually improving economic conditions – Sinhalese settlers inserted themselves in the old Wedda territories. At first only being labourers for the Weddas, soon they easily got ownership rights in the vast jungle areas where land was so cheap. And although nowadays both parties deny any mixed marriage, anthropological inspection, the Registry lists and casual crossexamination test to the contrary. But the new mixture seems to have concerned only the lower strata, i.e. the lower Wedda clans and the lower Sinhalese castes. There is no doubt that such a kind of mixture has existed earlier, too, if only not in such relatively large scale as it is nowadays happening among the remaining tiny Wedda groups. The race mixtures during more than two millennia easily explain why, as it was evident during my expedition, a unification of the archaic Wedda features in one individuum today (and also during the whole period from which we have pictures of Wedda people) has been extremely rare.

Based on the report of a mixed race Wedda, Lewis 8 describes the fusion of Weddas in the Westminster Abbey area which formerly had around the old Góvind-Héla in the Máha-Wédi Ráta (Great-Vedda-Country) been a main area of the Wedda: “….his grandparents belonged to a clan….who lived in a wild state in the Lenama forests, but in time those who survived of this clan became reconciled to their Sinhalese neighbours, and at last came to associate with them and ultimately, by marrying and intermarrying, they abandoned their forest life and settled in and aroud Salawe, or Hallowa Rata.”

Among papers recently shown to the author by chance in the Registry in Bulupítiya (Nílgala Kórale) were several Sinhalese-Wedda mixed people listed by their names. For a systematic study of this process of intermingling it would be now the most opportune time and also a last

8 Lewis, F.: Notes on an exploration in Eastern Uva…Journ. Ceylon Branch R.Asiat.Soc. 1914,XXIII, No. 67, pp.276- 293, 10 Taf., Colombo 1916

possibility. Unfortunately time and financial means of my expedition prevented working in this direction.

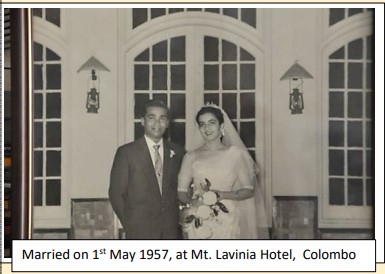

The family tree of T a l d é n a M é n i ka might serve as an example how the old noble families of Eastern Ceylon are interspersed with Wedda blood from the long lucky times of this people and, moreover, how the marriages in the country itself – which were absolutely normal – can be taken in a very limited way only to represent a further racial sinhalesization of lineage. She is the wife of William R. Bibile, the head of the ninth generation of the lineage and the mother of Charles W. Bibile, the current family head, who, like his father, grandfather and great

grandfather, holds the office of Rátemahátmaya (District Official or Administrator) of Wélassa.

There is also a Wedda chief appearing as the primogenitor of the family of Taldéna Ménika: Nádena Kumára Vánni Unnéhe.9 His office had been near Bókotuwewátte in Wáttekélle, in the high mountains north from Bádulla (the provincial capital of Uva), where nowadays since long no Weddas are living any more. He got married to Ponnára Bándara Galagóda, a girl from a noble family (as the name Galagóda tells, i.e. roughly “von Felseneck”). She had been “at the court of Kumára Sínha, Prince of Uva, at Bádulla”10 and should therefore have been a kind of lady-in-waiting, married to an officer of the Palace Guard.

The names of the offsprings of this couple, the First Parents of the Taldéna family, are immediately and exclusively Sinhalese. This is regularly true for all cases known to me, and this makes genealogical research more difficult. The extremely long names and richly adorned titles here, mostly shortened without changing the meaning, are an additional difficulty, as is also the extremely frequent use of the same first names. But again, this latter circumstance makes the titles valuable for identification, although even they are rather variable and changed several times during the lifetime of a person. Sometimes, in the closest family circle, individuals bearing the same name – and this is happens rather often with siblings – were distinguished by loku = big and punchi or hin = small, as can be seen from the family trees. That the personal names had played a rather minor role could already been inferred from the historical data for the Bibile family, where all chronicles only talk of “the Bibile Mudiyánse”. This genealogical problem holds also nowadays true for the Weddas. Very often they are not able, even with their

9 Vánni = Wánniya = Wedda chief, Unnéhe = general title, such as „His highness”

10 Genealogical table of the Bibile family, p. 52, M.S.

best and honest will, to exactly tell the name of their wife, their mother or just their own name, and they sometimes are only properly determing it after having asked their fellow tribals. It often also happens that they change their names: thus, e.g., the Vidáne (chief) of Hénnébedde, Poromóla11 simply took the name of the first husband of his second wife, i.e. Síta Wánniya.12 On the other hand, they recount for you subito and without hesiting the most complicated degrees of relationship – this is because they represent for a Wedda the real names for the person he has to deal with.

Apart from the features of name-giving described above, the ancient chronicles offer another difficulty, namely an indifference towards exact dating. In the documents, the historicity of events is always fixed by geographical, not by chronological orientation. The place where the king or fiefholder stayed and the local circumstances of previous or contemporary events play the preeminent role. Even recently, a priest could at once indicate the name and residence of the king under whose rule his dagoba had been built, when I asked him – but he could not give me any hint at the date.

This is why any exact chronological data are absent from the family tree of Taldéna Ménika. The only reference point is again Kumára Sínha holding court in Bádulla, on which event I currently don´t have any detailed information. The only possibility to approximately determine the date of the Sinhalese mixing with the old Wedda tribe is by counting the number of generations. According to the pedigree it dates back four generations. Mrs. Taldéna Ménika lived from 1869 till 1919. If we take 25 years for one Ceylonese generation, the racial mixing of Sinhalese and Wedda people may have started around the year 1769, that means, in the second half of the 18th century. The descendents of this family continue to live in Bádulla up till now.

It is evident that these old families whose members had been Dissáwas (Province chiefs) and Rátemahátmayas (District chiefs), are deeply rooted in the land. Due to the excellent intellectual and human qualities by which a great deal of the family members are excelling, due also to their love of the country, their impartiality and loyalty to their duty they are, even in our times, valuable administration bodies of the British government. A letter of a high British officer, dated March 4th 1913 and addressed to the Rátemahátmaya William R. Bibile can serve as

11 Good photo in C.and B. Seligmann: The Weddas, Cambridgen1911, Table VII

12 Good photos of him found in Seligmann, op.cit., Table V-VI

interesting evidence, because it acknowledges and at the same time admires “the strong feudal ties” that connect this family to the land.

In this connection I might also touch upon an important and for the Bibile family fatal event because it is related to the problem of the cultural-biological position of the Wedda – the Kandyan Rebellion on which unfortunately an in depth historical study is lacking up till now. It started in 1817 in the Uva province which until the beginning of British rule of 1815 had not yet experienced any domination by foreigners, and was organized by the Dissáwa of Badúlla. The execution of the British resident by arrows of Wedda troups at the road from Badúlla to Bibile – nowadays there is a memorial on the spot – was the signal for a general uprising. At this occasion the Wedda had been – and for the last time at that! – auxiliary troops of the Kandyans. According to a popular tradition, about which for understandable reasons the world will never get correct details any more, the young Rátemahátmaya Hinbanda of Bibile with his Weddas is said to have played a leading role at the execution. Long after the uprising had been oppressed in the Northern old Kandyan mountain districts, the fights continued in Uva, roughly until about 1822. The province was completely devastated. The Bibile family finally flew to the wild mountaineous region of the Eastern inner jungles where the Weddas of the old Moráne clan – relatives of them, as tradition has it -dwelled on the Danigála rock. The family was forced to purchase its return at the price of about 4/5th of its extensive landed property.

Additional data for the racial history of the Bibile family and its relation to the Wedda is made available by the current anthropological material, offered on the one hand by the family itself, and on the other by the last existing group of their traditional ancestors, the last Weddas of the old princely clan of the Moráne, settling in the Danigála mountains.

The p h o t o s from table 1 show the grandfather and the father of the current Rátemahátmaya, as well as himself and his son. The description of the grandfather, given by the anthropologist Emil S c h m i d t from Leipzig who must have been in Bibile about the beginning of August 1889, is quite accurate. S c h m i d t says:” After a long time came….the father of the Rátemahátmaya, in European dress, a beautiful Sinhalese head with a high forehead and long

rolling white beard.”13

Indeed, Abesúndare Bibile had been the characteristic anthropological

typus of a distinguished Kandyan, the north indian blood of his father Hinbánda absolutely dominating and the old Wedda blood of his mother Loku Ménika absolutely not recognizable any more. Completely different it is with his son, although his mother is the last representative of

13 E. S c h m i d t: Ceylon. Berlin 1897, p. 72.

an old purely Kandyan noble family full of rich traditions.14 E. S c h m i d tdid this already notice, too; he describes the then Rátemahátmaya as follows:” He was yet a young man, Sinhalese, but with his long, straight, pitch black hair, parted in the middle and combed back, with his hard featured, bony face, the dark piercing eyes, strongly protruding aquiline nose he reminded me more of a Red Indian than of a native of Ceylon…. His movements and manners were polished in a European way.”15

Indeed, on the group photos preserved by the family, the old Rátemahátmaya´s looks differ from those of the average type of the Kandyan nobility. His nose is rather high, as is typical for the “Aryan” (better to be called north indid from the racial point of view) inhabitants of Ceylon. But at the same time it shows a considerable width at the nostrils. Wide, distended nostrils, however, are one of the best marks of the Weddas, as also the protruding cheekbones that might in a large face look “bony and Red Indian”. By chance I found a passage in L e w i s16

with a quite similar description of a guaranteed mixed Wedda breed: “ The general cast of features is reminiscent of the North American Indian, in that the nose and cheek bones are strongly pronounced.” Examples of Weddoid formes of noses see on tables 2,6 and 7. The wide distended nostrils seem to be a highly characteristic feature of Weddas and Wedda mixed people, they also reappear in his son, the current Rátemahátmayam in a very expressive way (see table 1).

14 Bibile Waláue ( Waláue = seat of Nobles) preserves documents and silver swords, presented to this family by Sinhalese kings.

15 E. S c h m i d t, op. cit.,p. 39

16 F. Lewis, op. cit., p. 287

Read More Details – Return of the Ancestors – Sharing an Intangible Heritage – By Kavinda Bibile, Carola Krebs & Maria Schetelich

Ranil Bibile

Carola Krebs

Maria Schetelich

Based on the Family Tree compiled by

Baron Egon von Eickstedt

From documents provided by

Ratémahattaya C.W.Bibile