Flying to the Northern Warfront in the 1990s Part 2 – by Dr Gamini Goonetilleke

Source: a surgeon’s tales “reminiscence of a surgeon” – dr gamini goonetilleke

Personal Experiences in Managing Battle Casualties in the North

Personal Experiences in Managing Battle Casualties in the North

The care for the injured soldier is an essential element of soldier morale and has been, for centuries in warfare.

- It is of utmost importance to make sure that medical facilities are available to soldiers when they were injured.

- It has also been shown that the availability of effective medical care improves combat performance and that their sacrifices are appreciated.

In my previous post, I dealt with the necessity of civilian surgical teams flying to the war front in the North and the issue of managing the armed forces personnel injured in conflict at the Base Hospital, Palaly, situated within the High-Security Zone in Jaffna.

The Armed Forces did not have adequate surgical teams at the onset of the war.

The Government Hospital in Jaffna was not accessible to the armed forces personnel injured in conflict.

THUS, THE CIVILIAN SURGEONS HAD TO STEP-IN TO TREAT THE INJURED IN THE MILITARY BASE HOSPITAL WITHIN THE HIGH-SECURITY ZONE IN PALALY, JAFFNA.

Many surgeons volunteered their services due to the urgent need.

In the management of VICTIMS OF TRAUMA from any cause, a well-recognised system exists and is practiced throughout the world. The same system can be adopted in managing the war-wounded although there are difficulties at times due to the many variables that are present in a war situation. The adoption of that system is for the benefit of the injured TO REDUCE THE MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY. The system involves the following:

- First aid at the site of injury

- Care by Paramedics – resuscitation, arrest of bleeding, initiate intravenous infusion

- Communication with the hospital providing emergency care

- Transport to the Emergency Department in Hospital

- Emergency care in Hospital

- Tertiary care / physical and psychological rehabilitation

This article will discuss the management of the injured on these lines. Before discussing the management of the casualties, it is necessary to outline the facilities that were available at the Base Hospital, Palaly within the HSZ and about the medical teams attending to the injured.

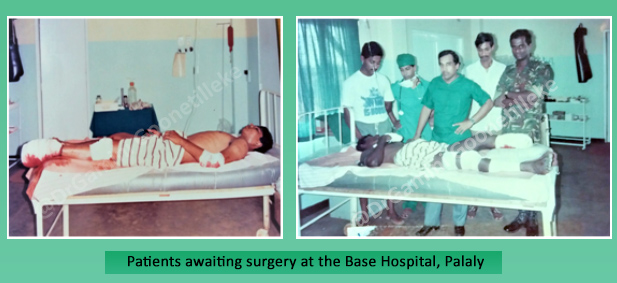

The Base Hospital, Palaly in the 1990s

The Palaly Base Hospital situated within the HSZ in the military base was established in 1986 to treat the armed forces personnel injured in conflict. It was a small hospital coming under the purview of the Sri Lanka Army Medical Corps. The hospital is situated adjacent to the airport for ease of transferring casualties to and from fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters.

In the 1990s, this hospital had one operating theatre (OT) with two operating tables, around twenty beds for the severely wounded and a larger section for those with minor injuries and the walking wounded. The operating theatre had the basic surgical instruments necessary for life-saving operations. A few operating theatre technicians assisted inside the OT. There was no Intensive care unit attached to the hospital. While the ground floor was for the surgical patients, the first floor was occupied by soldiers suffering from health problems such as malaria and other infections. A small X-ray unit was available for carrying out basic X-rays. The blood bank had to be supplied with blood from Colombo or Anuradhapura. The laboratory facilities were primitive. There was also an outpatient department (OPD) with a doctor for treating minor ailments.

Civil Medical Teams from the Ministry of Health

The staffing at the hospital was a major issue during the early phases of the war. This was in respect to the junior medical officers, anaesthetists and surgeons. The armed forces did not have the required number of medical officers/anaesthetists and there were no surgeons in the armed forces at that time except for a few volunteers in the medical corp. The Ministry of Health requested consultant surgeons attached to hospitals under the purview of the Ministry to volunteer their services in the Northern war front. A few surgeons/anaesthetists volunteered their services and were sent to the Palaly Base Hospital on a rotation basis to serve there for a period of about 7 -10 days on each visit.

The surgeons who volunteered their services flew in aircraft of the Sri Lankan Air Force to Palaly, Jaffna to serve at the hospital situated within the HSZ for a period of about 7 -10 days at any one time.

I was one of them and this story is about my personal experiences in treating the war-wounded at that hospital in the 1990s.

On many occasions, I was accompanied by the junior staff in the hospital in which I worked as well as the Anaesthetist with whom I worked in that hospital. The Military and the Ministry permitted me to take my staff, and they were glad as it was not easy to find volunteers to serve in the war front.

THE AERIAL ROUTE WAS THE ONLY ROUTE AVAILABLE FOR

- Medical teams visiting the Northern war front to treat the injured in war.

- Taking the injured to hospitals in Anuradhapura and Colombo

Initial problems in managing the injured

While the different aspects of managing victims of trauma mentioned earlier is ideal, the armed forces faced many issues in managing the armed personnel injured in conflict during the initial period of the war. The main issues were

- Shortage of manpower

- Deficiencies in trained hospital staff

- Lack of equipment/resources

- Primitive facilities in the hospital

- Guerrilla warfare

- Devoid of ambulance support

“Our soldiers were confronted with a trained, equipped and dedicated terrorist group”.

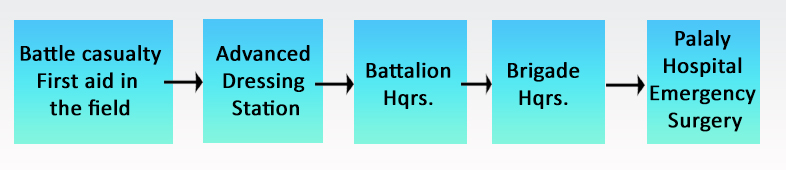

However, the problems were slowly but surely overcome with more men enlisted, better training for medical and para-medical personnel, better coordination of the care of the injured, more equipment, staff and facilities, etc. to achieve a higher standard of care. The process followed in managing a casualty from the battle-front to the Palaly Hospital is as shown in the flow chart below.

Management of Casualties in the North in the 1990s

There were no Trauma Teams, Specialised Surgical Teams and Field Hospitals. All the emergency life-saving operations were performed at the Base Hospital, Palaly. On most occasions, the surgical team comprised a surgeon, anaesthetist and a medical officer assisted by nurses and operating theatre assistants. The number of medical staff was increased when a military operation was planned and executed in the Jaffna peninsula.

Deaths in the Battlefront

Most of the deaths in the battlefront were due to

- Injury to vital organs – brain, heart, major Blood vessels, decapitation, dismemberment, mutilating injuries of the extremities, traumatic amputations, etc

- Severe bleeding – internal/external

- Obstructed airway

A word of caution: Some photographs may be revolting

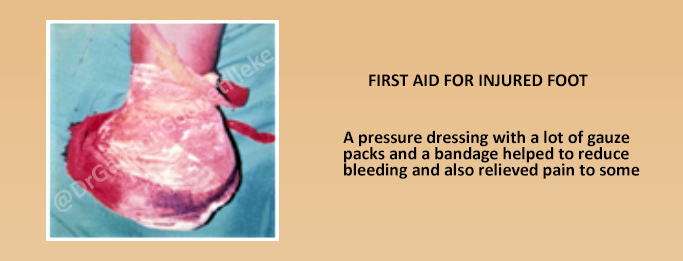

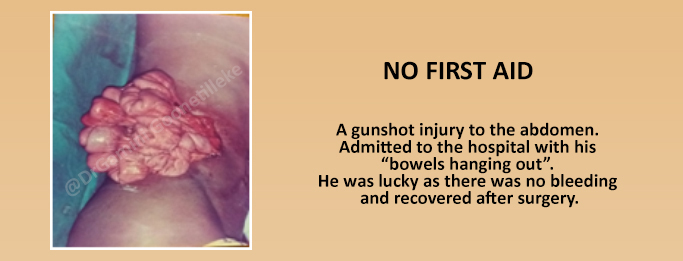

Whereas some of the injuries were fatal instantaneously, there were others where efficient first aid at the site of injury or at the earliest possible moment could have saved lives. THIS HIGHLIGHTS THE IMPORTANCE OF FIRST-AID IN THE FIELD

First-aid

During this period there was no organised system to provide first-aid and the combatants had no idea of this all-important aspect of care of the injured. Many were brought to the hospital without any first-aid in the field. I saw a few who were dead on admission from bleeding due to lack of first-aid. There was also the problem of getting the injured victims out of the location as soon as possible as this was guerrilla warfare initially, and this also posed problems. The aim was to get the victim to the Base Hospital as soon as possible and hope for the best with the care in the hospital.

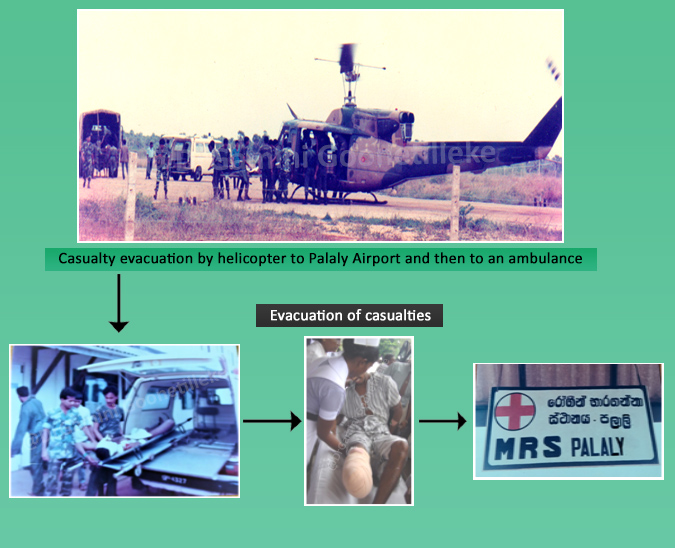

Taking Casualties to Hospital and the Lack of Communication with Hospital

The transport of casualties to the hospital was in differing types of vehicles depending on availability and accessibility. These included tractors, army trucks and jeeps, ambulances and rarely field ambulances. Bell 212 helicopters were used for transport if the helicopter could land safely at the location to pick-up the injured. The helicopter with the casualties landed at the Palaly airport. The casualties were then transferred to an ambulance and dispatched to the hospital nearby. There was no communication with the hospital on most occasions and casualties were brought-in to the hospital without any notice. We were not prepared but had to rush-in to take care of the injured.

That was a problem!

Management in the Hospital

Herein, I describe the role of the surgical team at the hospital rather than the details of the surgery. The main function of the team was to identify and perform surgery on those who were seriously wounded and to stabilise them before transferring them to a tertiary care centre in Colombo or Anuradhapura.

On admission to the hospital, it was necessary to check the airway, breathing and circulation (bleeding) – the basics of first aid denoted as A B C and take appropriate corrective action. Resuscitation with intravenous fluid/blood was carried out, if necessary. Thereafter, the patients had to be categorised according to the severity of the injury to decide on the priority for treatment. This is the principle of TRIAGE, a French term that simply means to “sort-out” and was an essential requirement especially when many patients were admitted simultaneously.

TRIAGE

The patients were categorised as follows:

- Patients with minor injuries that were managed in the emergency department or self-help and did not need surgery

- Patients with injuries that required surgery. In this group, there were three categories

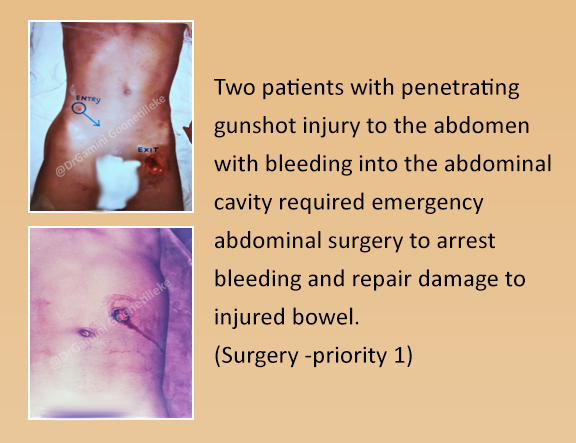

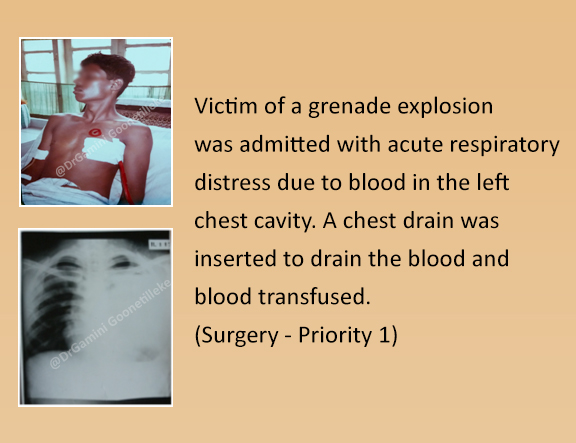

Priority 1 – These patients required emergency resuscitation and surgery to relieve asphyxia and/or to arrest bleeding due to chest and abdominal injuries. Patients with multiple fractures and extensive muscle damage also belonged to this category because they had lost a fair amount of blood and were in shock.

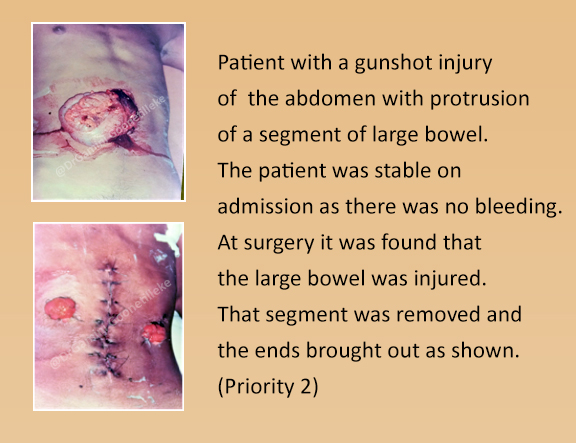

Priority 2 – Those with injuries that required early surgery and included those with abdominal injuries without bleeding (damage only to viscera), chest injuries without asphyxia, and injuries to blood vessels.

Priority 3 – those with injuries where surgery was less urgent as there was no threat to life.

Some victims were dead on admission or the injuries were so severe that recovery was not expected.

Many victims had injuries to soft tissue. It is a recognised fact that all war injuries are contaminated. Injuries to soft tissue required wide excision of all dead and contaminated tissue. Failure to do this process thoroughly could lead to gas gangrene or tetanus. These injuries were kept open without suture in keeping with principles of management of war injuries to be sutured later or skin grafted.

THE PRINCIPLE OF DELAYED PRIMARY CLOSURE WAS APPLIED TO ALL SOFT TISSUE INJURIES

The recommended antibiotic was Penicillin intravenously. A course of tetanus toxoid was also initiated. Surgery was performed under general anaesthesia. Ketamine was also used in combination with Diazepam to anaesthetise selected patients and they proved to be very useful in patients undergoing surgery.

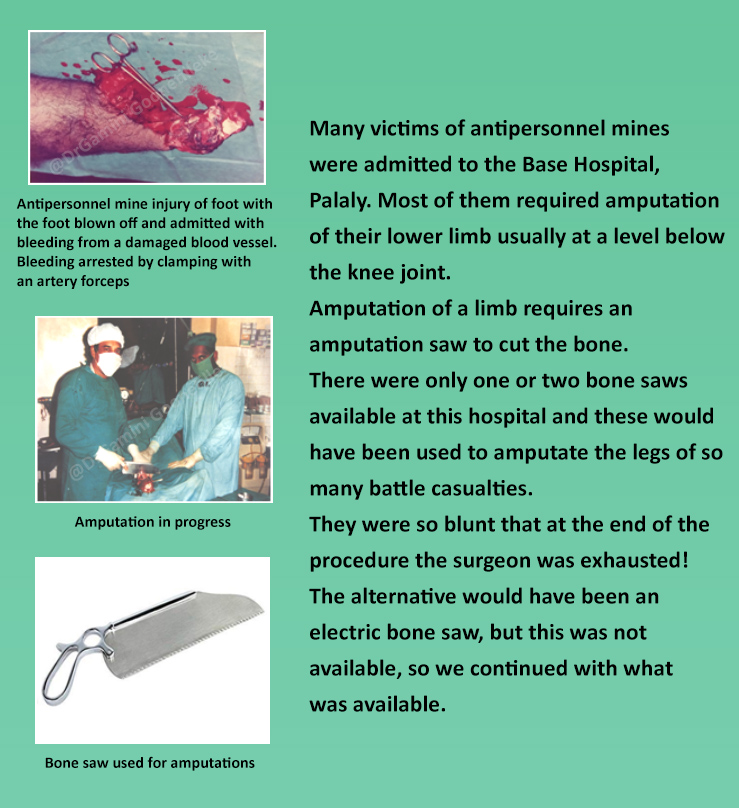

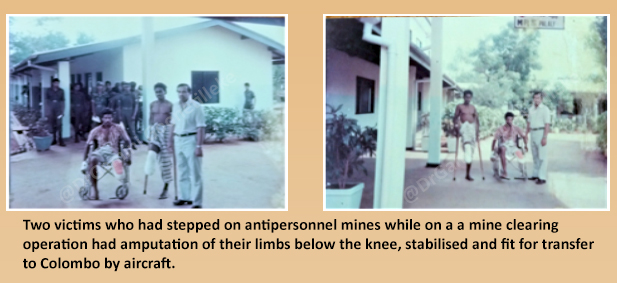

Many victims had amputations, most of them being injured after stepping-on or handling antipersonnel mines. These amputations were performed at the Base Hospital, Palaly whenever possible before transfer to Colombo as delay would lead to the infection spreading up and sepsis.

Transfer of patients to Colombo or Anuradhapura

Once the surgery was done and the patient’s condition stabilised, they were transferred to Colombo or Anuradhapura hospital for further medical care, rehabilitation and other military protocol. The transfer of these patients was in Sri Lanka Air Force aircraft – Y12, Y8, Avro 748, and Antonov 32B. As mentioned in Part I, they were transport planes and not special aircraft for the evacuation of casualties and thus there were difficulties in accommodating them in the aircraft. The transfer was made possible by removing seats so that more patients on stretchers could be placed on the floor of the aircraft. For the patients, it was not easy especially during take-off and landing. But they had to cope with the situation as there was no alternative and the doctors too had to sit on the floor with the patients. That was the adaptation to the situation and everything went off well.

Reference – History of Medicine in Sri Lanka (1948 – 2017), Sri Lanka Medical Association. 2018. History of Military Medicine. Page427-466