From Ceylon to Australia: Migrant Journeys, 1860s-to-2010s – By Michael Roberts

Source : thuppahis

Earl Forbes, whose chosen title in The Ceylankan is “Ceylon/Sri Lanka to Australia: Arrivals and Survival”

Ceylonese/Sri Lankans have entered Australia for a variety of reasons during the past one and a half centuries. The far greater number of these arrivals occurred in the second half of the twentieth century and first two decades of the 21st century. Early arrivals go as far back as the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

Figure 3 Queensland sugarcane plantation workers. … [placed as frontispiece because of its striking character

Early Arrivals

Before Australian Federation on 01 January 1901, there is evidence of arrivals from Ceylon, mainly to Queensland and a very small number to Victoria and Western Australia. In 1882, a sizable number of Ceylonese arrived in Queensland as indentured labour. With the expansion of sugar cane planting in Queensland at that time, there was an ever-present need for labour to work the plantations. In November 1882 nearly 500 Ceylonese arrived by sea in Port Mackay, Queensland. Some 300 disembarked in Mackay and the rest were taken to Bundaberg. The 500 Ceylonese had been brought to Queensland under a private arrangement between business Agents in Ceylon and Queensland plantation owners. No government agencies were involved in this enterprise in either Ceylon or Queensland. The deal included paid passage to Queensland, with the requirement that the worker was contracted to serve for five years. At the end of the five-year contract, the worker was to be repatriated to Ceylon with the return passage paid. Workers were entitled to rations and an annual wage during the tenure of the contract. Some were even given a plot of land for a home garden. In some instances, the terms of the contract could have been varied to meet particular circumstances. There are no detailed figures as to how many of these workers returned to Ceylon at the end of their contract and the number that stayed behind. Suffice to say many went back and some stayed on to build a life in Australia, not so much on the plantations but as cooks, waiters, artisans and domestics.[1]

The 500 who arrived in Queensland in 1882 were not the first to get to Queensland from Ceylon. In the 1870ies there was a rush to the Torres Strait Islands where rich Pearl Fishing resources were discovered. Not only were the natural pearls here of great value, but the Torres Strait Island seas had also comparatively large deposits of good quality pearl shells. Pearl Shells were used to make the product, ‘mother of pearl.’ Mother of pearl was sought after for making high quality buttons, buckles, handles for exclusive cutlery and similar high-priced products. In an era where diving gear had not yet begun to be used, experienced workers (both bare skin divers and boatmen) were highly sought after. In Ceylon pearl fishing in the Gulf of Mannar had gone on from time immemorial. In fact, so well was pearling known, that in the 1860ies the famous music composer Bizet, wrote the opera, ‘The Pearl Fishers’, using pearl fishing in ancient Ceylon as its backdrop. It was only logical that the North Queensland Pearl Fishery operators would look to Ceylon to source cheap labour for the growing industry. In the Torres Strait area, Thursday Island became the base from which the larger and more prominent pearling operations were conducted. As early as 1879, four Ceylonese, (called Cingalese at the time) are recorded being employed as boatmen. It was not long before enterprising businessmen in Australia were able to arrange for recruitment of a larger group of workers from Ceylon. In 1882 some 25 Cingalese were recruited to work on Thursday Island. Entry of Ceylonese workers to Thursday Island after 1882, continued on a less formal basis. Although numbers were small, as the population on Thursday Island was comparatively sparse, the additions were significant. Also, there was more occupational variety in the arrivals from Ceylon. In addition to divers and boatmen there came shell cleaners, cooks, domestics and small traders. The requirement that the worker had to return to the country from which he had been recruited, does not seem to have been strictly enforced in all contracts. This facilitated the continued stay on Thursday Island of those among the Ceylonese arrivals who wished to stay on. In the years following, right up to the 1940ies, the Ceylonese on Thursday Island left a lasting impression on the Island’s township. At the height of their influence there was a Cingalese quarter, a place for Buddhist worship, and even an area where their preferred groceries were sold.[2] Another account refers to a Ceylonese, who having studied dentistry by correspondence, set himself up as a dental surgeon on Thursday Island. [3]

Thursday Island in early days

An extract from Stanley Sparkes and Anna Shnukal’s work on, ‘Sri Lankan Settlers of Thursday Island, states: –

‘While their exact numbers are unknown, the Sri Lankans remained a salient group until the outbreak of World War II, distinctive enough to be singled out by contemporary observers. Some of the early immigrants became commercial fisherman and owners of boats for hire; others took out hawkers’ licences to sell jewellery and other curios made from tortoise shell, pearl shell and pearls to tourists and visitors. ………………………………………………………………

For more than six decades, the Sri Lankan Community made significant contributions to the economic, religious, social and cultural life of Thursday Island. All of them have left, the Mendis and Saranealis families being the last to end their association. Little physical trace of their presence remains, but the prominent business families are still remembered. Not only did they provide goods and services not available elsewhere, but, through their acts of generosity and willingness to share their heritage with the entire community, they formed enduring relationships with their fellow residents, regardless of ethnic origin or religious affiliation.’ [2]

Arrivals from Ceylon to the other Australian Colonies at this time appear to be much less than to Queensland. Before the Pearl industry resources were discovered in the Torres Strait, they were found to exist in the Northwest of Western Australia, around the township of Broome. This was as early as the 1860ies. The demand for workers in the industry attracted labour from several Asian countries. Because of their expertise, persons from Ceylon appear to have been recruited to work in the Western Australian pearling industry as well. Their numbers and identity are somewhat obscure because they were often grouped with others and referred to as, ‘Malays’. Asian (or foreign} workers in the industry were stated to have come from Japan, China, Philippines, Ceylon, Malaysia and some Pacific Islands.

In the nineteenth century arrivals from Ceylon to the Colony of Victoria came about broadly for reasons similar to those which attracted arrivals to Queensland and Western Australia. In 1851, gold was discovered in Ballarat, Victoria. This event, followed by discovery of gold in some of the other colonies, led to an influx of a large number of persons from all parts of the world to Australia (gold rush). Victorian Government sources on the subject of immigration history comment as follows: –

‘Sri Lankans (formerly referred to as Ceylonese) have been settling in Victoria since the 19th century. They were first counted in the 1871 census, when 58 people were recorded. Like Sri Lankan settlers elsewhere in Australia they probably immigrated as labourers or gold prospectors. [4]

The other ‘industry’ which used predominantly Asian labour in the 19th century was camel transportation in Central and Northern Australia. Cameleers and camel transport operators did not come directly from Ceylon. Most of the labour and animals came from Afghanistan, with lesser arrivals from India and the Middle East. However, there is an indirect connection with Ceylon. It appears some Afghans used Ceylon as a launch pad to Australia. There is mention that a camel transportation operator, Gool Mohamet, although born in Afghanistan, worked in Colombo for a few years before arriving in Australia in the late 19th century. Gool Mohamet was a successful camel transport operator, but his notoriety rests more on the fact that he married a French woman at the Kalgoorlie Mosque in 1907. The French woman, Desiree Ernestine Adrianne Lesire, converted to Islam and changed her name to Mariam Bebe, at the time of her marriage to Mohamet. [5]

The White Australia Years [1st half of the 20th century]

On 01 January 1901, the 6 Australian Colonies came together to form the independent Nation of Australia. Regarding immigration and population, one of the first actions undertaken by the Commonwealth Parliament was to pass legislation strictly limiting entry to Australia. The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 established the base for future migrant entry to Australia. This Act set up a harsh and effective tool, (the Dictation Test) for turning away from Australia, any non-European. The Act stated that the following persons could be prohibited from entering Australia: –

‘Any person who when asked to do so by an officer fails to write out at dictation and sign in the presence of the officer a passage of fifty words in length in an European language directed by the officer’.

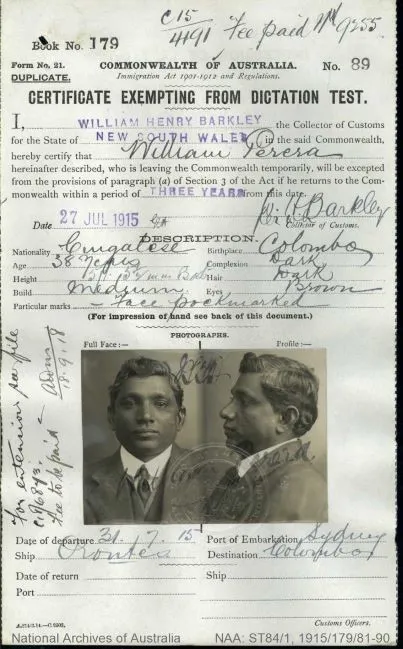

Whilst new arrivals from Asia were almost completely shut out, persons who had formerly been domiciled in the Australian Colonies were not subject to the Dictation Test. However, if a person who was not a citizen left Australia, he would be subject to the Dictation Test on re-entry, unless he had an Exemption Certificate. Non-citizens who had built up enough wealth to be able to travel outside Australia and return could apply for an Exemption Certificate. Figure 1 is an Exemption Certificate issued to Mr. William Perera, permitting him to travel outside Australia and re-enter without having to sit a Dictation Test on re-entry.

Figure 1 Certificate Exempting from Dictation Test.

Restrictive legislation coupled with a view among many in society at the time that the white race was superior to coloured, led to arrivals from Asia (including Ceylon) coming to a stop or at best a trickle. As mentioned above arrivals from Ceylon to Victoria at the time of the gold rush (1871 census) was recorded as being 58. Sixty years later (in 1933) the number of Ceylon born in Victoria was 130; an increase of 72 over sixty years. [4] In 1901, the Australian Immigration Department put the number of persons in Australia, born in Ceylon, at 609. Thirty-two years later the number was stated to be 638; an increase of 29 over three decades. [6]

A fair go for all [2nd half of the 20th century to recent times]

The years following the end of the 2nd World War saw the World changed significantly, particularly in South and Southeast Asia. India, Pakistan and Ceylon gained independence after centuries of British rule; Indonesians threw out the Dutch rulers of their country, and in China the Communist Party seized power. In the context of all these momentous changes, one would have expected Australia to fall in step and change restrictive policies, such as permitting immigration only from Europe. However, the White Australia Policy was alive and well even after the end of the 2nd World War. In 1947 Immigration Minister Arthur Caldwell stated: –

‘We have 25 years at most to populate the country before the yellow races are upon us.’

Arthur Caldwell was correct in that there was an urgent and great need to bring in more migrants to Australia for the further development of the country. However, his view was a short term one in that he looked only to Europe to satisfy the demand.

At about this time the Burghers of Sri Lanka were being disadvantaged due to political, economic and social changes in their homeland. This gave rise to Sri Lankan Burghers looking to other countries, such as Australia, as a viable permanent home for themselves and their families. In the late 1940ies the Burghers began their push to enter Australia, citing the fact that they were of European ancestry and ‘British Subjects’ as well. For the first decade after Sri Lanka gained independence, arrivals to Australia were in the main Burghers. The years after the 2nd World War, up to about 1960, saw an increase in the number of arrivals, but not great enough to be of significance. In 1954 the number of Sri Lankan born in the Australian population was 1,961. Seven years later it was 3,433.[7]

In the next 2 decades arrival numbers start to pick up sharply compared to the 1950ies and 1960ies. The increase in the number of arrivals from Sri Lanka and arrivals from other Asian countries was a consequence of a slow but progressive dismantling of the White Australia Policy. The first concession was made in 1957 when, ‘non-Europeans with fifteen years residence, were permitted to apply for Australian citizenship. The next year legislation pertaining to immigration was revised after more than a fifty-year lapse.‘The Migration Act 1958’ abolished the harsh and archaic Dictation Test and set up a more liberal Visa system for entry to Australia. Not long after the legislation was revised, Immigration Minister Alexander Downer (father of present-day politician Alexander Downer Jnr.) declared that ‘distinguished and highly qualified Asians’ would be considered as suitable migrants to Australia. In 1966 the entry door was opened further to: –

‘well qualified people on the basis of their suitability as settlers, their ability to integrate readily and their possession of qualifications positively useful to Australia’.

Finally in 1973 the Whitlam Government, as a matter of Australian Immigration Policy decided to: –‘totally disregard race as a factor in the selection of migrants’.Immigration Minister at the time, Al Grassby, added: –‘The White Australia Policy is dead; give me a shovel and I will bury it’.

Australia’s more liberal immigration policy had a very positive effect on the number of arrivals from Sri Lanka. Australian Department of Immigration figures for Sri Lankan born persons in the population show the dramatic increase: –

1961 3,400

1971 9,100

1981 16,900.

By 1981 arrivals from Sri Lanka were not drawn as before, mainly from the Burgher community, but also from the Sinhalese, Tamil and Muslim communities. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 1976 Census (unpublished) data puts the ethnic composition of Sri Lankan born in the population at, Burghers 8,546; Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims at 5,759 and others at 561, making a total of 14,866. [8]

In the years immediately following the 2nd World War, Australia had accepted as migrants from Europe, large numbers of both skilled and unskilled labour. In the late 1960ies and thereafter this changed. Australia was now looking more precisely for skilled and semi-skilled workers as well as settlers under a broader ‘family’ category. In 1977 Immigration Minister Michael Mackellar laid the foundation for recognition of the third future stream of migrants to Australia, viz. the humanitarian intake.

In Sri Lanka those seeking to migrate were predominantly from the middle and upper middle classes, living in the cities, and mostly educated in English. The Sri Lankan supply of skilled and family stream potential migrants was in line with demand in Australia. Sri Lanka was able to supply skilled technicians, process workers, clerical and administrative staff and para health workers. Some of the tertiary qualified arrivals encountered problems. Although restrictions to entry had been lifted for admission to Australia, prejudice prevailed regarding the acceptance of Sri Lankan higher education qualifications. Many had to return to study in their field of expertise before being able to work at professional level in Australia. Those professionally qualified in Sri Lanka who chose not to re-qualify under Australian educational standards, often worked at sub-professional level or ventured into allied new careers (in most instances very successfully).

In the final two decades of the 20th century the ‘family’ stream was most popular for the flow of migrants to Australia. For approximately 11 years, (from 1985 to 1996), the number of migrant arrivals to Australia from all countries under the family stream exceeded the number of arrivals under the skilled migration program. It could reasonably be concluded that arrivals from Sri Lanka followed this pattern, (i.e., family stream arrivals exceeding skilled stream). Regarding arrivals under the humanitarian intake scheme, Museums Victoria states: –

‘Ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka in 1983 resulted in a significant intake of migrants under the Special Humanitarian Program’.

The cumulative result of arrivals from Sri Lanka under the various visa categories pushed up the number of Sri Lankan born in the population to: –

1981 16,900

1992 43,200

2002 61,400.

In the last year of the 20th century and the first two years of the 21st century a new class of arrival, (for the first time in significant numbers) from Sri Lanka is added to the arrivals list. These were asylum seekers who arrived by boat. Sri Lankans and others, mostly from South Asia, comprised the second wave of asylum seeker arrivals to Australia by boat; (the first wave was from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in the late 1970ies and the 1980ies). Because the Howard Government had introduced ‘the Pacific Solution’ after the ‘Tampa Affair’ in 2001, the later of these arrivals ended up in third countries or in having to go back. Accordingly, these Sri Lankan arrivals do not feature in a material way in ABS population numbers. Ironically asylum seeker boat arrivals from Sri Lanka to Australia peaked in 2012 and 2013; a few years after the end of the 26-year-old Civil War, in 2009. In 2012 Sri Lanka was the largest source country for boat arrivals (direct) to Australia. But only a small percentage (11%) were accepted to enter Australia and subsequently to be included in ABS population numbers. The somewhat open migration policy of the Gillard/Rudd governments was shut down partly in the final months before the 2013 election and more comprehensively under the new Abbot government. In the eight years 2009 to 2016, (financial years), net migration numbers from Sri Lanka to Australia year to year are as follows: –

Year Number Year Number Year Number

2009 6,500 2010 4,600 2011 3,500

2012 4,500 2013 5,100 2014 3,700

2015 4,100 2016 4,200.

Overview

Although small in number when compared to arrivals from the top two countries England and New Zealand, Sri Lanka has been for many years an important resource for Australia’s migrant intake. In 2011, the number of Sri Lankan born in the Australian population was put at 100,000 (0.4%). By 2016 the number had gone up to 124,000. In 2021 there were 146,000 Sri Lankan born and the percentage had gone up to 0.6 of total population. Sri Lanka also currently holds the 10th position in the Table of overseas born in the Australian population, (2020 figures).

Based on data obtained from the 2016 Census, an interesting overview can be gleaned as to where Sri Lankans choose to live in Australia and their lifestyles. Of the 2016 total of 124,000, nearly 75% chose to live in Victoria and New South Wales, (Victoria 63,000 and NSW 33,500). In the other four States and two Territories the distribution was: Queensland 11,000; Western Australia 9,000; South Australia 4,000; Australian Capital Territory 3,000; Northern Territory 1000 and Tasmania 500.

In regard to lifestyle, Sri Lankans are more prone to getting married and staying in the relationship. Among Sri Lankan born 71.2% are described as ‘married’. The Australian born ‘married’ group make up only 43.6%. The Sri Lankan born, divorced/separated figure was at 5.6%, whilst the Australian born divorced/separated rate is much higher at 11.8%.

Like a majority of migrant communities, Sri Lankan born rank high on the tertiary educated table. 41.6% of Sri Lankan born held a bachelor’s degree or higher qualification. This compares extremely favourably with the Australian born score of 19.6%.

Finally, house-proud Sri Lankans once again lead the way when it came to the size of dwellings. 40.5% of those born in Sri Lanka lived in residential dwellings with four or more bedrooms. The percentage of Australian born occupying dwellings of the same size was 34.7%.

‘At last he rose, and twitch’d his mantle blue:

Tomorrow to fresh woods and pastures new’.

Milton

REFERENCES

[1] W. S. Weerasooriya: ‘Links between Sri Lanka and Australia’.

[2] Stanley Sparkes and Anna Shnukal: ‘The Sri Lankan Settlers of Thursday Island’.

[3] W. S. Weerasooriya: ‘Links between Sri Lanka and Australia’.

[4] Museums Victoria: ‘Immigration History’.

[5] www.farinarestoration.com: ‘The Gool Mohamet story.

[6] Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, (DIMA), reports. Multiple references.

[7] Australian Bureau of Statistics, (ABS), reports. Multiple references.

[8] S. K. Pinnawala Sri Lankans in Melbourne.

[9]] Photos courtesy National Archives of Australia.

*****************