KAYMAN’S GATE: PETTAH’S DUTCH LEGACY

Source: Sunday Observer, December 25, 2016-12-25

Source: Sunday Observer, December 25, 2016-12-25

If, like me, you are a lover of Sinhala songs, you will no doubt have been mesmerized by the Sunil Edirisinghe song “Kayman dorakada indapan mama enathuru Selesssina” (Selessina, please wait at Kayman’s Gate till I come). Since this song is about the various old landmarks of Colombo, I was always curious to find out where this actually is. Then I found out that it is actually in Pettah, just a few minutes’ walk from my office.

Once Colombo’s smartest residential area, Pettah is now the city’s bazaar, a jungle of streets jammed with bargain-hunters, herds of trucks, Lorries, carts and the ubiquitous three-wheelers where the Dutch colonial facades still survive proudly beside gleaming new mercantile shops. After visiting Colombo’s Dutch Period Museum (featured last week), our next visit was to Kayman’s Gate and Wolfendhal Church. A visit to Pettah isn’t complete without at least visiting these two Dutch monuments.

A sense of anticipation gripped us as we left the Dutch Period Museum and strolled along Second Cross Street towards the busy Main Street. Having reached Main Street, we continued along Main Street. On either side, as we dodged down Main Street, shops were bursting with garments hung like bunting from merchants’ doorways.

Crocodiles

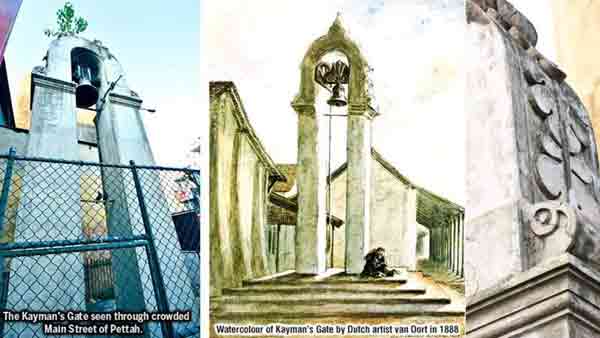

Suddenly, we glimpsed a curious sight through the gauntlet of street vendors and bustling shoppers, beyond the huge bill boards adorning buildings. Unmoved by the chaos around it, an ancient belfry stood defiantly, symbolizing Pettah’s proud past. It is all that remains of Kayman’s Gate stands where the crocodiles, or caymans, from the Beira Lake once scavenged.

In Portuguese times, the Colombo Fort was fortified by a ring of 12 bastions with intervening ramparts and supported by a moat, flanked on the east by a crocodile-infested lake and on the west by a boulder strewn shoreline.

To the south of the canal named De Revir is the Roa de Casa, while to the north of it is the Roa Directo which is the Main Street of today’s Pettah. At the end of this street is seen the Poorta Reinha, (Queen’s Gate), the principal exit which was a massive gateway built at the mouth of a tunnel under the eastern rampart, with access via a drawbridge over the moat. These were later called Kayman’s Gate and St. John’s River respectively. This gate opened on to the road to Hanwella, which followed the left bank of the Kelani River. The Dutch captured the city in 1656 and held possession of it.

After capturing Colombo, the Dutch set themselves to alter not only the fortifications but also the streets, which were laid out on a more regular grid pattern and are still so, today. The Dutch called the present Pettah, ‘oude stad’ or ‘old city’, because they found this to be the active centre when they took over. The walls and fortifications round the ‘oude stad’ were allowed to remain, but they were subsequently removed, though a mud wall on the east near Kayman’s Gate survived until British times.

It is all that remains of Kayman’s Gate at the end of the Main Street of the Pettah on the right leading to 4th Cross Street. Today, the Department of Archeology has built a fence around the base which is confined to a small rectangular space. Near the age old bell, crows build their nests. Public executions were held at its foot; now an Electricity Board transformer and commercial establishments block access to the site.

Worshippers

In Dutch times at the foot of the Wolfendhal Hill (present eastern end of Main Street) stands the old belfry with the bell which summoned worshippers to prayer at Wolfendhal church. The bell is said to date back to the 16th century, during which time it hung in the Portuguese church dedicated to St. Francis. It is said that this church once stood in the Royal city of Kotte. The Dutch reoccupied this city which had been abandoned in 1565. The bell was found among the ruins and later mounted on the belfry at Kayman’s Gate.

In the Dutch period, the Main Street was known as ‘Koning’s Straat’ and stopped at Kayman’s Gate, after which the belfry is named. ‘Kaaiman’ is the Dutch for crocodile, from which Kayman is probably derived. In the years of Dutch times, there had been crocodiles in the Pettah because the crocodile infested Beira Lake extended right up to Kayman’s Gate via St. John’s River. It is said that crocodiles from Beira Lake once scavenged for food along the St. John’s River close to Kayman’s Gate.

Another historical anecdote says that the Dutch have minted a large number of VOC coins in the building close to Kayman’s Gate because of its security and protection provided from the crocodile-infested moat.

The bell still hangs majestically in the belfry which was decorated with some flower motifs on both sides. Although it did service as a Church bell for special services at Wolfendhal Church in the recent past, it seems to be desolated and neglected today.

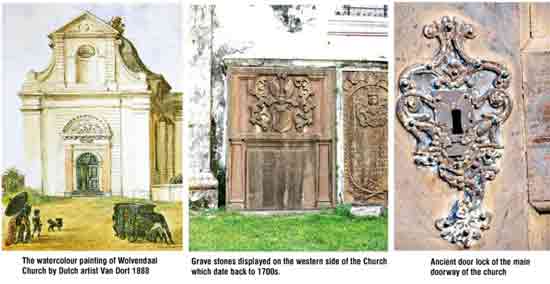

After visiting Kayman’s Gate, we strolled towards Sea Street crossing Wolfendhal Street and walked a little up a hillock. We continued on Central Road and crossed again to Wolfendhal Street where the imposing edifice of Wolfendhal Church stands crowning the hill and overlooking the city and harbour of Colombo. Built in 1749 in the Doric style, with walls made of clay ironstone 1.5 metre thick, upon which the gables were raised, it is the finest historic monument of the Dutch period and has been left intact despite the changes that have come all round it. Its transepts, directed to face the four points of the compass, are facaded by four lofty gables supported by pilasters with spreading scrolls at the side. Its roof is composed of four brick-lined, plastered domes which radiate from a central tower. The high roof galvanized sheeting is painted in red.

Carved into the gable over the southern entrance are the initials IVSVG. That associates the building with the name of Governor Julius Valentyn Stein van Gollenesse who was chiefly responsible for its construction. The date (1749) is seen over the doorway.

On the southern façade, prominently displayed is the date AD 1749 which is evidence of the year the foundation was laid. Strolling around the church premises, we witnessed the western part of the exterior walls of the church displaying many gravestone dedications dating back to the 1700s in remembrance of loved ones.

‘Dale of wolves’

Wolfendhal Church is just one of four remaining structures in any decent state of preservation built by the Dutch in every settlement of importance. Wolfendhal literally means ‘dale of wolves’ and has probably been derived from the marshy lowlands haunted by jackals lying immediately outside the walls of the fort of Colombo.

When Colombo capitulated in 1796, many Dutch officials, settlers and clergymen returned to Holland (Present Netherlands) or retired to Batavia. In 1800 there were only about 900 Dutch inhabitants left on the island. It is to them and their descendants the Burghers, that credit must be given for the preservation of one of the few monuments in Colombo which stands as a memorial to the oldest Dutch institution in Sri Lanka.

We said goodbye to these magnificent edifices thinking for how many years can we see them as they were once managed and venerated by people who lived in the past. Go there and experience the places for yourself. It is a worthwhile excursion for anyone with history in their hearts.

No Comments