Richard Austin: the tragic fall from West Indies allrounder to shoeless street beggar-by Ashley Gray

In an extract from his new book, Ashley Gray charts the downward spiral of a once-talented cricketer

Richard Austin and Alvin Greenidge of the rebel West Indies XI during an ODI against South Africa in Cape Town in 1983. Photograph: Adrian Murrell/Getty Images

Source:Theguardian

On 14 March, 2015, the pews of the byzantine-revival Holy Trinity Church were stuffed with the heavyweights of Jamaican cricket and society: ex-Test players, administrators and ministers of government. The man they had come to pay tribute to, Richard Austin, had, in death at least, been forgiven the sins of life.

But as one eloquent speaker after another recalled Austin’s tragic fall from West Indies allrounder to shoeless street beggar, it became apparent that many of those well-dressed orators were seeking their own kind of salvation. Forgiveness for the way Austin, whose primary sin was playing cricket in apartheid South Africa, had been treated by his countrymen. It was a reminder, the presiding priest said, that “we are all mere sinners, here to help each other in love to make it home to God”.

In many ways the phases of Austin’s life hold a mirror to Jamaica’s own expedient moral consciousness. As a young, elite-level sportsman from the ghetto area of Jones Town, he was feted for transcending a poor background, a rare example of social mobility in a nation dogged by the remnants of slavery; as a former Test cricketer he was shunned and scorned for visiting a country that practised a modern form of slavery; and finally, as a middle-aged vagrant, he was tolerated and humoured, the target of both earnest sympathy and benign neglect.

Years earlier, in 2003, sitting in a gutter next to Tastees, a pastry chain restaurant in the commercial district of Kingston known as Crossroads, Austin, then 48, began to tell me his story. Wiry and weather-beaten, eyes bloodshot with the effects of rum and cocaine, his conversation veered between the tragic and comic as he first asked me to call his “good friend” Kerry Packer. “I can come to Australia and play for Sydney or NSW,” he rasped, while politely refusing a swig of rum from one of the gang of drifters he was running with. “Kerry Packer to me was like a gift in the cap.”

Then he addressed his cocaine habit. “When you live on the street you live with street people. If you want to party then sometimes I have to do it [cocaine].”

The truth was he didn’t have to flounder on the streets. He part-owned a house and car in the uptown suburb of Mona, which was looked after by his brother Oliver. It was as if the gutter, where no man dare judge another, was the only place he felt at home.

Richard Austin in the Kingston commercial district of Cross Roads in 2003. Photograph: A Gray/R McCormick

He acknowledged old Jamaican cricket friends had tried to help him but he complained that the money he got from coaching jobs was barely enough to cover his laundry expenses.

“I hope you can get through to Kerry Packer and World Series Cricket and see if you can do something for me,” he cried, as he disappeared into the night, clutching the 2,000 Jamaican dollars his friends had wrangled out of me as payment for chatting.

It was the kind of delusional conversation Austin would have time and time again in his final years as a disjointed life meandered to its inevitable conclusion. Yet despite growing up at a time when deadly violence between warring political tribes was rife in Kingston, there was outwardly at least, little to suggest of the turmoil that would plague Austin in later life.

A top-level table tennis player in his teens, and promising footballer with first division club Arnett Gardens, Jeff Dujon, his former Jamaica teammate still regards Austin as “probably all-round the most talented cricketer I played against”. He could bat as opener or in the middle order, bowl offspin and seam, and keep wickets to a standard some said was almost the equal of Dujon. In his pomp, enthusiasts labelled him a potential “right-handed Gary Sobers”, critics a “Woolworths Gary Sobers”.

But he would only play two Tests, both in 1978, dropped along with Desmond Haynes for signing with Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket troupe. An irresistible offer in the region of $20,000 for two years was that “gift in the cap” Austin would reminisce about when his life had spiralled out of control.

The boy from Jones Town had hit pay dirt. But Austin was inexperienced with handling large sums of money and it showed. Flush with Packer dollars, patrons at nightclubs such as Skateland and Epiphany in New Kingston became the beneficiaries of Austin’s rampant generosity. “He’d see people he knew and ask what are you drinking; you’d say a beer and he would bring you a whole case of beer. He would shout the whole bar,” Dujon says

Jamaican software consultant Patrick Terrelonge had been instrumental in convincing Kerry Packer to bring World Series Cricket to the West Indies. He was also in charge of paying the players. When the money was sent back to the Caribbean he looked after the disbursements. Most of them had their money sent to sports marketer IMG where it was invested. Not Austin.

“I remember Austin coming into my office and asking me if his money had come in,’” Terrelonge says. “This particular tranche was for US$16,000. I said, ‘would you like to put it in the bank or send it to IMG?’

“He said to me: ‘Mr Terrelonge, how much does a BMW cost?’ I said, I think about $8000. He said: ‘Send the money down to the BMW dealer.’ I said: ‘Are you sure that’s what you want to do?’ He said yes. What would you like to do with the other $8000? He said: I’ll buy two then. I tried to dissuade him but he eventually did it.”

Austin developed a reputation as an entertaining and friendly combatant Down Under. “He was different; I got on well with him, but he lived for the moment,” says former Australian captain Greg Chappell. “He was more laidback than the most laid-back West Indian. You could say he was Joe Cool before it had even been invented.”

But his chilled demeanour could be explained in part by excessive marijuana use, which manifested itself in a slack approach to training. When news of a rebel West Indies cricket tour of apartheid South Africa swept the Caribbean in late 1982, he was no longer a serious contender for a position in Clive Lloyd’s world-beating side. He was also an easy target. A cheque to the value of US$100,000 was 75 times what an average Jamaican could expect to earn in a year. For a man with a hedonistic lifestyle to finance, it was a no-brainer.

Austin’s wife, Molly Biggenot-Austin, was introduced to him at a Kingston night club in 1980. They quickly fell in love. “Richard was awesome. He was always smiling and having fun,” she says. “That’s what drew me to him.”

But she was adamant he should reject the South African Cricket Union’s advances. “I told him he wasn’t to go,” says Austin-Biggenot. “Him say: ‘But I want to make a better family life.’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t need you to make a better family life. I can do with whatever you are getting from coaching with the Institute of Sport,’ plus I worked at a bank. But the money was too sweet. I don’t say I don’t like money, but I’m not going to sell my soul for money and that’s what he did.”

She wasn’t the only one urging him not to go. The hostility from the political and media class was summed up by the Minister Of Youth and Community Service, Errol Anderson: “Let me go on the record as hoping those Jamaicans who put their feet on South African soil and compete in sports there, will never be allowed to enjoy their ‘blood money’ in Jamaica.”

His words would prove prophetic. Austin compiled a patient 93 in one of the so-called Test matches against the Springboks, but it was his only performance of note on the 12-match tour.

Back home in Jamaica, the subject of the rebel tours continued to stir emotions. Unlike World Series Cricket, which had media support and was portrayed as a just battle against a backward-looking establishment, the rebels were viewed in newspaper reports as soulless mercenaries aiding the cause of apartheid.

Apart from a lifelong Test cricket ban, Austin was also shut out of the Senior Cup and stripped of his job as a coach with the Institute of Sport. He had buckets of money, but nothing to do. With unemployment running at 26.4%, and the brand damage associated with employing a “blood money” cricketer, there were no businesses willing to stick their neck out to hire him. Without the lifeblood of cricket, his tendency towards self-destruction exploded.

His wife copped the brunt of it. Their plan to buy a house together disintegrated – a casualty of Austin’s new drug of choice: cocaine. “He took the money behind my back and invested it in coke. I think it was the rejection – he didn’t know how to deal with that. He wanted something to dull the pain.”

During the day while Molly was at work, Austin would booze and ingest drugs with his old nightclub friends, often not returning until the early hours of the morning, stoned and drunk. When husband and wife did catch up, Austin was regularly consumed with jealousy. It was an emotion that could bring out an even uglier side.

Former Jamaica batsman Mark Neita says his teammate was well-known for “putting his hand on his better half”. It reached absurd proportions during a Shell Shield match against Guyana when the police arrived at Sabina Park to arrest Austin for beating up his then girlfriend the night before.

“We had won the toss and Danny Germs [Austin’s nickname] was opening the batting when the police came. So they said ‘Look, the moment he gets out, we will take him away.’ But he batted and batted because he knew the police were after him. He batted straight to lunch, and he batted after lunch and made 118. Eventually the policeman left.

“When I asked him about it, Danny’s explanation was that he thought she was cheating. There were a lot of moments like that.”

Biggenot-Austin says his violent behaviour tore them apart. “I remember one time our baby son Ricardo was sick and I had to carry him to the doctors. My girlfriend was going to take me but it was too late so I went back home. He knocked me out on the floor and I could not believe it. My hand was broken.

“He thought I was going out to look at men, but I had my son with me trying to get a drive to the hospital. He was jealous. That was what the coke was telling his mind to think… because he wasn’t like that before.”

She left Austin in 1984.

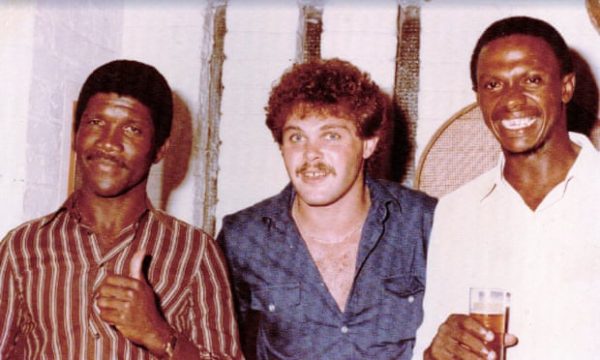

Richard Austin (right) with fellow rebel Lawrence Rowe (left) and a friend at a party during the first rebel tour of South Africa in 1983. Photograph: Ray Wynter

The one-time Jones Town hero was on a downward spiral. Jamaican society turned a blind eye to his suffering and the suffering he was causing others. In their eyes, he had brought racial shame to a proud people and the consequences were his and his alone to endure. “Austin was totally ignored,” former Jamaica captain Maurice Foster says. “From celebrity status to nothing.”

Clubs that once welcomed his patronage were now turning him away. Neita remembers the owner of an establishment where Austin had once shouted the bar champagne kicking him down the stairs, “because at the time he had lost it, and nobody wanted to be associated with him anymore”. It was not an isolated incident.

Fast bowling great Michael Holding represented the views of a significant portion of the island when he said: “These men [the rebels] are worse than slaves. If they were offered enough money they would probably agree to wear chains.”

Jamaica has an honourable history of fighting racial inequality. Its successful slave revolts lit the fuse of liberation across the Caribbean. Understandably, bitterness dies hard in a land where any hint of skin colour prejudice provokes justifiable outrage.

But at times it seemed that the reaction to Austin’s plight bordered on spiteful; he had reaped what he had sown and now he was living his comeuppance. It touched on a dark current in the Jamaican psyche: the notion of “bad mind”, a tendency to resent the success of others – “dem nuh want see we prosper” – the flipside of which was a peculiar pleasure in their demise.

But as time wore on, the public spectre of Austin’s ostracism, a troubled former Test cricketer living out his demons on the street in full view of the nation, began to elicit concern and even sympathy. Yet it would not be enough to halt his slide into destitution – and the shadows of cricket history.

This is an edited version of a chapter in the book, The Unforgiven, by Ashley Gray, available now.

No Comments