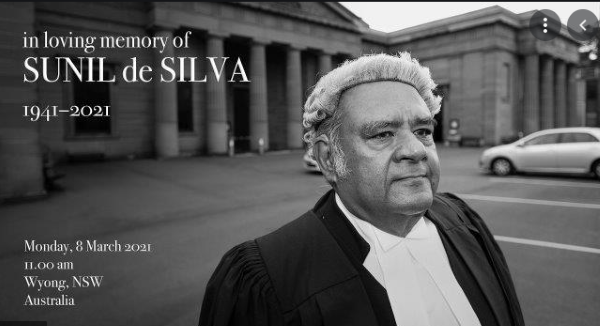

The misunderstood role of the Attorney General in Sri Lanka By Sunil de Silva P.C

Source:-sundaytimes

I have been concerned by comments I read in the newspapers that there appears to be a misconception in the minds of the public of the role of the Attorney General in Sri Lanka.

This is not surprising as the Attorney General is a public servant who holds the power to make quasi-judicial decisions.

While the public are aware that the Executive cannot direct a judicial officer as regards the exercise of a judge’s judicial functions, some views expressed in news articles suggests that the Executive can, and indeed should, direct the Attorney General in his decision making process.

This misconception probably arises out of the belief that a lawyer retained by a client has to present views that the client wishes to place before a Court.

Even in a normal lawyer-client relationship, the lawyer’s duty to the Court overrides the wishes of the client and the lawyer should not mislead the Court either on a question of law or fact.

The Attorney General and the lawyers in the AG’s Department are in a different lawyer client relationship. A State Counsel who prosecutes in a criminal matter is not a ‘mouthpiece’ for the victim.

His or her role, contrary to popular perception, is not that of securing a conviction at any cost, but rather that of a ‘minister of justice’ seeking a fair verdict making disclosure of any material – even that which is favourable to the accused.

A daunting role indeed, and a fact that, I as a young and enthusiastic Crown Counsel, had been ‘informed’ on occasion, with asperity, by senior judges.

The role of a prosecutor is no different in Australia where, I currently practise, and in England. The duty of disclosure to the defence of relevant material, even though disadvantageous to the prosecution, is contained in prosecution guidelines and strongly stressed in these jurisdictions.

To appreciate the position of the Attorney General, it is relevant to examine the history of the establishment of the Office of Attorney General.

On a historical parameter, the Office of the Attorney General evolved from the ‘Advocate Fiscal’ during the Dutch Rule, through ‘The King’s Advocate’ or ‘The Queen’s Advocate’ during the early British administration to ‘The Attorney General’.

The Legislative Council which established the Office of the Attorney General, provided that the Attorney General and the Solicitor General were to have the same powers as the respective office holders in England as well the powers as the Law Officers of the Crown had exercised. The first holder of the Office of Attorney General was Hon Francis Flemming.

It is significant that when many jurisdictions which followed or adapted the British Legal system made the position of the Attorney General as a Member of the Cabinet and consequently a post held by a politician, we continued the distinction between the position of the Minister of Justice held by an elected or appointed Member of Parliament and that of the Chief Legal Officer who exercised quasi-judicial functions.

The powers and functions of the Attorney General assisted by the Solicitor-General, the Crown Proctor and Crown Counsel evolved through the recommendations of the Donoughmore and Soulbury Commissions transferring some of the powers of the Legal Secretary to the Attorney General and others to a Minister of Justice.

The 1948 Constitution adopted these recommendations, except that advice on constitutionality of Bills was routed through the certification by the Speaker to the Governor.

When Sri Lanka became a republic the power to appoint the Attorney General was moved from the Governor General to the President.

This position continued after the 1978 Constitution established an Executive President who derived his authority directly from election by the people.

The point that this brief history intends to make is that the role of the Attorney General, even though vested with additional functions through the 1972 and the 1978 Constitutions, remained a quasi-judicial, non-political position.

It is noteworthy that the 17th and the 19th Amendments to the Constitution place the Chief Justice, the Judges of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal, the Members of the Judicial Service Commission, the Attorney General and four other officials in a constitutionally guaranteed position of security from removal from office.

This is obviously a safeguard against any of the holders of the Offices who are required to act independently in the formulation of their decision, not having to look over their shoulder in fear of being subject to threats of dismissal without due process.

It is also necessary to advert to the fact, which the public may well be aware, but lose sight of, on occasion, that a decision announced as “The Attorney General rules that ….” regarding an issue is usually not the product of a single mind.

As most people are aware, the Attorney General as the Chief Legal Officer of the State has three streams of matters that converge on him or her: Primarily criminal matters, civil matters, where the State or a State Corporation is a party, and constitutional matters such as the consistency of the provisions of a proposed legislative instrument with the Constitution and fundamental rights applications to the Supreme Court.

In the normal course of events any matter that reaches the Attorney General’s Department begins as a file handled by a State Counsel under the supervision of a Senior Officer.

An issue of complexity or of public interest would move up within the levels of seniority and reach the Attorney General after consideration of an officer at Deputy Solicitor level.

Even where the Attorney General is directly contacted, it would be normal for the matter to be discussed with the Solicitor General or an Additional Solicitor General.

In considering a question of law or the application of the law to a particular set of facts is often a “quot homines tot sententiae” [as many opinions as there are men] situation and while the final decisions rests with the Attorney General, it is almost always a joint decision for which the Attorney General takes responsibility.

It is axiomatic that in making an interpretation or an assessment any human being could make an honest mistake and it is equally human for anyone who had expressed the opinion that proved to be correct but had been over ruled to say “I told him it was wrong”.

It is equally tempting, and probably pushed by parties adversely affected by the Attorney General’s decision, to let it be known that the decision had been contrary to a recommendation by another officer.

In the sphere of judicial determination, the establishment of an appellate hierarchy acknowledges human fallibility.

It would be manifestly unfair to postulate that the decision had been motivated by undue pressure from someone in authority or some other dishonest motive, merely because the decision was proved wrong.

A decision that there is insufficient evidence to institute a prosecution, or begin other relevant proceeding would invariably infuriate a victim or a ‘whistle blower’ reporting a crime or a fraud, and it would be hard for the complainant or victim to make the objective assessment that a judge or quasi-judicial officer has to make.

A victim who honestly believes that he has accurately identified his attacker would find it hard to accept that an unbiased assessor may have a reasonable doubt about mistaken identification when other circumstances point in that direction.

Unfortunately custom and precedent practice frowns upon a judicial officer or a quasi-judicial officer offering, in the public domain, an explanation or the rationale for a decision.

In the case of the officers of the Attorney General’s Department, manifestly incorrect and even maliciously incorrect attribution of improper motives have to be borne with fortitude in the hope that time will reveal the truth!

(The writer is a former Attorney General of Sri Lanka)