The Place of the Physician in Sri Lanka’s Society

Source:Island

“The Best Physician is also a Philosopher”

Galen of Pergamon (c.129 – 216 AD )

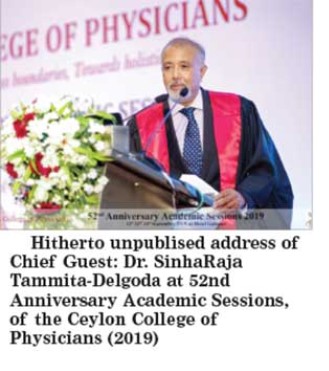

An institution, a learned society and a body of practitioners, the Ceylon College of Physicians stands at the apex of medical learning and practice in Sri Lanka. For over half a century, the College has fulfilled an integral role in medical education and the maintenance of professional standards. As an institution, it has played a valuable part in the building of our nation. As a scholar, a historian and a Sri Lankan, it is a privilege and an honour to address its 52nd assembly.

In a thought provoking conclusion to the 50th Anniversary Commemorative Volume, Dr Panduka Karunanayake, President Elect for 2017, explores new horizons. In an increasingly technological age, he underlines the great need to master the human and social aspects of healing. A profession that truly cares for its patients in every sense of the word, must seek to understand and shape the future. This demands that the physician not only advise patients but that he guide society. If as Dr. Karunanayake suggests, the physician is to shape the future, he must endeavor to understand the human being, his society and his environment.

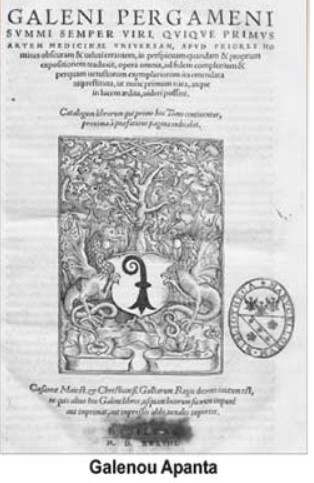

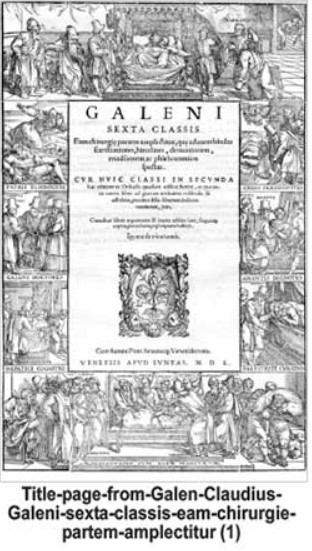

This was a philosophy which was articulated by one of the fathers of western medicine Aelius Galenus better known as Galen of Pergamon. The most celebrated medical authority of the Roman empire, Galen was one of the greatest physicians and surgeons of the ancient world. He has authored more books still in existence than any other ancient Greek. With the exception of Aristotle and Plato, he ranks as one most influential intellectuals in the classical west.

This was a philosophy which was articulated by one of the fathers of western medicine Aelius Galenus better known as Galen of Pergamon. The most celebrated medical authority of the Roman empire, Galen was one of the greatest physicians and surgeons of the ancient world. He has authored more books still in existence than any other ancient Greek. With the exception of Aristotle and Plato, he ranks as one most influential intellectuals in the classical west.

Born into the intellectual and social elite, Galen was son of a wealthy architect with scholarly interests and he received an excellent education. He travelled and studied widely, spending several years at Alexandria in Egypt, the greatest medical centre of the age. Returning home he spent four years tending a troupe of gladiators, eventually become the personal physician to a succession of Roman emperors.

Described by the Emperor Marcus Aurelius as “First among doctors and unique among philosophers,” Galen strongly believed that science and medicine must be practised in the context of human desires and needs. For him, medicine was an interdisciplinary field where science, ethics and the arts were all interwoven He saw himself as both a physician and a philosopher and believed that the study of philosophy would make for a better scientist, hence his short treatise The Best Physician is also a Philosopher.

In an eerie evocation of a contemporary dilemma Galen attacks the medical culture of his day which

“…encourages people to value wealth over virtue. For, “it is impossible to pursue financial gain at the same time as training oneself in so great an art as medicine; someone who is really enthusiastic about one of these aims, money or medicine, will inevitably despise the other.”

Galen advocated the study of arts and letters as an essential component of scientific study. In another work An Exhortation to Study the Arts, he warns against specialized isolation and lists several arts which he categorizes as divine gifts because they are useful to life. Alongside natural science and medicine, he also lists poetry, music, and philosophy. This underlines his belief that physicians must be specialists who were not only technically competent but also humane and morally responsible. According to Galen, proper, precise scientific inquiry was indeed ‘useful for life’. However, it could not be accomplished by scientists who were not properly trained in the other arts, because they would not then possess the humanity, the sensitivity, to do that science properly.

There does not appear to be a great distance between Galen’s creed and the requirements of contemporary medicine. A modern day physician like a philosopher is trained to think, to inquire and to ask questions. It is perhaps one of the foundations of his long and rigorous education. A good physician, like a good philosopher is always asking questions. It is by asking the best possible questions that he can make conclusions and diagnose.

A real philosopher is always open to question. This is even more the case with medicine. The danger is that answers shut down questions. Therefore the physician must always be open to question. As it is a question of wellbeing, of life and death, these questions are always shifting, changing with the time and the moment. If as a physician one must come to a conclusion, one can only do that by becoming a philosopher. To do that the physician must be able to listen, to observe, to think and to question. He must have time and make time. Time to listen, time to ponder, time to think, to analyze and evaluate.

It is a dilemma which still lies at the core of modern medicine. In an age where the internet and artificial intelligence have made vast inroads into the credibility of the physician, what makes him special is that although modern technology can make diagnoses, it cannot take a judgement call. That judgement call still rests on the human element, the physician’s understanding of the social context- on factors such as belief, culture, environment, sustainability and cost. This will determine the success of the cure. As Dr. Karunanayake foresees, if the physician is to play a role in the future, he must endeavor to understand the human being, his society and his setting.

The history of medicine reveals that physicians have occupied a special role in many parts of the world. Classical scholars have always regarded the ancient Greeks as the fathers of western medicine. However recent research suggests that the ancient Egyptians practised medicine long before the Greeks. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, an Egyptian surgical treatise dating from 1600 BC suggests that medical practice was well established in Egypt 1,000 years before Hippocrates. This documents 48 injuries which were described, diagnosed and treated rationally through observation and examination. It is thought to be a copy of a much earlier work dating from the 3rd millenium BC by the Egyptian polymath Imhotep. Chief Minister to the pharaoh, a priest, a sage and an architect, over the ages Imhotep was gradually glorified and became a god of healing.

His counterpart in the Greek world was Asklepios, the son of Apollo. The legend goes that Asclepius become so skilled that Zeus, the king of the gods, feared that he might render men immortal. To prevent this Zeus slew him with a thunderbolt and over time like Imhotep, he too became a God. His shrine at the sanctuary of Epidaurus became known as the Asklepieion and it grew into the most important centre of healing in the Greek world. The legacy of Asklepios looms large in the Greek tradition of healing. Hippocrates formal name was Hippocrates Asclepiades, “the “descendant of Asclepios.” Galen too, we are told was not destined to become a physician and only took up medicine after the God Asklepios appeared to his father in a dream.

His counterpart in the Greek world was Asklepios, the son of Apollo. The legend goes that Asclepius become so skilled that Zeus, the king of the gods, feared that he might render men immortal. To prevent this Zeus slew him with a thunderbolt and over time like Imhotep, he too became a God. His shrine at the sanctuary of Epidaurus became known as the Asklepieion and it grew into the most important centre of healing in the Greek world. The legacy of Asklepios looms large in the Greek tradition of healing. Hippocrates formal name was Hippocrates Asclepiades, “the “descendant of Asclepios.” Galen too, we are told was not destined to become a physician and only took up medicine after the God Asklepios appeared to his father in a dream.

In Ayurveda, the system of medicine and lifestyle developed in Ancient India, the pre- eminent figures are Sushruta and Charuka. Sushruta is thought to have lived near Varanisi during the 6th-7th century BC. Regarded as the father of Indian medicine, he was the main author of the Sushruta Samhita, one of the most important surviving ancient treatises on medicine. The other medical text to have survived from ancient India, the Charaka Samhita, was authored by Charaka, who is thought to have practised throughout the Punjab between the 2nd -3rd century BC.

One of the oldest medical systems in the world is traditional Chinese medicine. This tradition has produced many leading figures. In the 5th century BC Bian Que (Pien Ch’iao) was the first to rely primarily on pulse and physical examination for the diagnosis of disease. He was followed by Hua Tuo (Yuanhua) the greatest surgeon in Chinese history. In 2nd century AD he became the first person in China to use anesthesia during surgery.

Throughout the ancient world the practice of medicine was associated with learning and skill, over time it become a divine gift. The physician was the incarnation of Imhotep, Asklepios, Hippocrates, Galen; he was a god, a seer, a sage, a skilled and deeply learned practitioner, a guide and a philosopher. Only in Sri Lanka however, was the physician a king.

The place of the physician in Sri Lanka’s society is documented in the island’s great historical chronicle, the Mahavamsa. Compiled in Pali by Buddhist monks, the Mahāvaṃsa and its successor, the Cūlavaṃsa, charts the history of Lanka from the 5th century BC to the 18th century AD. It is a remarkably accurate record, of seminal value for the history of India and Sri Lanka.

King Buddhadasa reigned between 341 – 370 AD. The Culavamsa recounts how he diagnosed, treated and cured patients from all walks of life. The chronicle devotes several whole sections to the practice and establishment of medicine and documents at least seven detailed case studies. This suggests that the physician had a very special place in this society and that his story was as important as the great warriors, builders, saints and the monks who shaped the history of Lanka. Each of these case studies tells us different things. Each concerns a different situation and elicits a deeply and carefully thought out remedy, based on reasoned analysis and evaluation.

In one case, it tells of how a man drinking water swallowed the eggs of a watersnake. The egg gradually grew into a snake. As it grew sucked at the man’s intestines, torturing the victim with pain. The man sought out the king, who questioned him. When he described the pain and related what had happened the king realized that a reptile must have formed inside the man. However as the reptile was lodged deep inside the intestines, the king refrained from cutting it out.

Instead he made the man fast for a week, starving the reptile within him. He then had the patient, bathed and rubbed with oil. This calmed and soothed him and he eventually fell asleep. The king knew that when he was asleep that his mouth would open. He tied a piece of meat to a string and dangled it over his mouth. Lured by the smell and driven by hunger, the watersnake reached for the meat. The king however, held the string fast and drew on it, gradually pulling the reptile out.

Another case concerned a Bhikku or Buddhist priest, the most venerated member of society. The bhikku had gone begging for alms and was given milk which had worms in it. The worms grew and fed on his bowels, causing agonizing pain. The king then asked leading questions. At what meal did the pain arise? What kind of meal was it and what was the nature of the pain? When the bhikku told him that it was a meal that he took with milk, the king recognized the symptoms.

Taking the blood from a horse, he gave it to the monk to drink. He then waited until he had drunk it all. Then he told him that was horse’s blood. The reaction was what he had anticipated. On hearing that he had drunk the blood of a horse, the monk vomited, spitting out the blood. The worms which had caused him such pain, came up with the blood.

Compassion and feeling made up an essential part of the King’s healing skills. There is a deep feeling for life in all its forms. This applied even to the most dangerous animals. Galen had concluded that even dumb animals are not entirely devoid of reason. In Buddhadasa’s most wellknown case, the king cobra, one of Sri Lanka’s most venomous reptiles, becomes a willing patient. As the king passed by, the cobra turned over onto his back to expose his underbelly so that the king could see the tumour growing on it. After observing the growth, the king reasoned with the reptile. Although he understood its pain, he dared not touch it. Understanding the king’s dilemma, the snake stuck his whole neck into anthill so that he could not hurt the king. Whilst the cobra was immobilized, the king slit open his belly, removed the diseased growth and applied a healing remedy.

This episode suggest a high level of surgical skill. It is underlined by another. A young man had drunk water which was full of frog’s eggs. Through his nostrils an egg had penetrated into his skull and evolved into a frog. As the monsoon approached the frog became more and more agitated, causing unbearable headaches. In this case the king appears to have resorted to immediate surgery. Performing a complicated and dangerous operation, he split the skull and removed the frog and then put the parts of the skull back together.

Ancient Indic society was dominated by caste and social taboos. Despite this and ignoring own his royal status, Buddhadasa cut across every social barrier and boundary to serve the suffering. In Indian society the lowest and most menial of tasks were performed by the Caṇḍālas, outcastes who worked as sweepers and scavengers. A Candala woman who had already had seven children, became pregnant for the eighth time. This time however, her unborn child was facing the wrong way in the womb. When Buddhadasa learned that this, he intervened to save the woman’s life. In the ancient world, birth and reproduction were the preserve of women and midwives. Socially this is a unique case. It is also a complex gynecological procedure.

The understanding of the human mind is an integral part of the physician’s craft. More often than not it holds the key to the patient’s condition and his recovery. In ancient times leprosy was a common condition. Lepers were shunned and regarded with horror and leprosy deemed a curse of the Gods.

The king noticed a leper, who upon seeing him, became enraged, striking the ground with his staff. In a previous birth the king had been the leper’s slave, it maddened him to see him riding his elephant and all he wanted to do was to kill him. Learning of this, Buddhadasa set his mind to winning him over. He sent one of his men to befriend the leper and share his anger. Pretending that he too was against the king, he invited the leper to stay at his house and help him destroy his enemy. The leper was bathed, fed and given beautiful clothes and a comfortable bed to sleep. One day, when he had become happy, contented and calm, Buddhadasa’s man served him food and drink, saying, “This is the gift from the king.” At first the leper refused and then refused again. Finally he accepted. Reaching out to the most diseased and most deeply troubled member of his community, the king was able to heal his mind. It is a clear demonstration of the power of empathy, feeling for and feeling with. It is from empathy that re assurance comes. So much of healing is in the mind. If the physician can take the time and make the effort, he has the power to do great good.

All these cases make one point. The physician truly cares and feels for all his patients, no matter who they are or where they are from. In his posthumous work Galen and Galenism (2002) the Spanish historian and Physician, Luis García Ballester (1936-2000) quotes Galen as saying: “In order to diagnose, one must observe and reason.” This is the dictum which King Buddhadasa embodies. He observes closely, listens carefully and questions keenly, making every attempt to form a picture of the condition. It is then he makes his diagnosis and decides on course of action. A demonstration of the power of the mind, sustained thought and inquiry, it is characterized by understanding and feeling.

The Cūlavaṃsa praises King Buddhadasa as a “Mine of Virtue and a Sea of jewels.” This perception is based on the king’s understanding of the human and social aspects of healing, his ability to care and feel. It is probably this tradition which lies at the roots of the well known Sri Lankan saying “If you cannot be a king, become a healer.”

This is the challenge which western science and learning faces in one of the world’s oldest living cultures. This context demands that the physician be conscious of the rhythms of a society, whose needs, values and way of life are often quite distinct from western norms and practices, often very much older. If as an invited guest, I can make one suggestion, it is that Sri Lanka’s physicians begin to study their past. For it is through comparative traditions that we learn deeply about ourselves.

If he is to truly guide as well as “Cure, Relieve And Comfort,” the Physician must also strive be a Philosopher.

He must not only ask the best possible questions, most of all like King Buddhadasa, he must care, be concerned and compassionate. For that he must have time.