Unbearable Reading: An Interview with Anuk Arudpragasam

Source:Sundayobserver

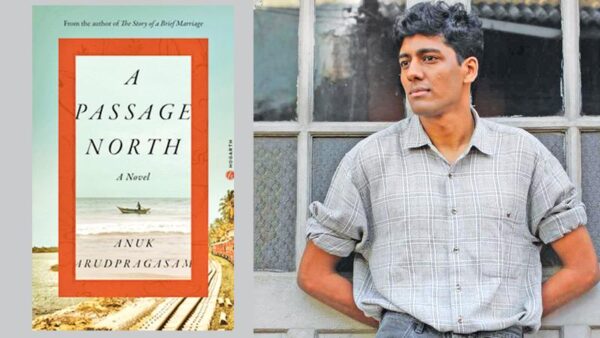

It is no exaggeration to call Anuk Arudpragasam’s first novel absolutely devastating. The Story of a Brief Marriage depicts Dinesh, a sixteen-year-old Tamil man—and yes, at sixteen Dinesh is in many ways a man, forced into a premature adulthood—in a refugee camp toward the end of the Sri Lankan civil war. Though Arudpragasam’s second book is more removed from the bodily experience of violence as portrayed in his first, the war still hangs heavy over the scope of the new novel.

A Passage North, an excerpt from which appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of this magazine, follows Krishan, a Tamil man who grew up outside of the war zone, as he makes his way north from Colombo to attend the funeral of his grandmother’s caretaker. It is an incredibly introspective work. Through the particularities of Krishan’s experience and inner life, Arudpragasam seamlessly unfurls ruminations on intimacy, trauma, and the passage of time.

The contemplative nature of A Passage North makes sense—Arudpragasam wrote the novel while studying for a Ph.D. in philosophy at Columbia University. While the war and its legacy are central to his work—they are “an obsession,” he says, and he looks forward to the day that he can write about something else—so, too, are the realms of literature and ideas. This came through in our lengthy conversation, which lasted nearly two hours. Arudpragasam jumps from novels to the politics of caste to philosophy to Sanskrit poetry to Tamil-language writing and back again with ease, drawing on stories, texts, and cultural history to illustrate his thinking.

The contemplative nature of A Passage North makes sense—Arudpragasam wrote the novel while studying for a Ph.D. in philosophy at Columbia University. While the war and its legacy are central to his work—they are “an obsession,” he says, and he looks forward to the day that he can write about something else—so, too, are the realms of literature and ideas. This came through in our lengthy conversation, which lasted nearly two hours. Arudpragasam jumps from novels to the politics of caste to philosophy to Sanskrit poetry to Tamil-language writing and back again with ease, drawing on stories, texts, and cultural history to illustrate his thinking.

Although he claims to be an impatient reader and writer both, Arudpragasam strikes me as patient, generous, and, above all, thoughtful, choosing his words carefully and often taking time to cultivate an idea. What resulted was the following much-abridged conversation, in which we discuss his work, influences, and process.

Q: What was your entry into writing fiction?

A: I didn’t come from a book-reading household, so my entry into books was arbitrary. It happened to be through philosophy books that I found at a bookshop close to my house. The first book I read was Plato’s Republic. Then it was Descartes’s Meditations and a book of lecture notes of Wittgenstein’s called The Blue Book. I tried to read Aristotle’s Ethics, but I stopped that after a while.

I read a lot of philosophy when I was fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, before I went to university. That was my entry into literature—I only really started reading fiction when I was in College. There was one book in particular, The Man without Qualities, by Robert Musil—he actually had a Ph.D. in philosophy. He has these long, digressive, essayistic sections in his book, which I haven’t read since I was twenty, so I don’t know how I’d feel about it now.

At the time I was very moved by the way he places philosophical questioning and response in a kind of living, bodily situation. Philosophical problems arise in lived context, in response to real situations, and in philosophy, academically, you don’t really ask or answer questions in that way. But I read that book, and it showed me that there was a place in fiction and novels for a lot of what interested me about philosophy. Actually placing these things in their lived context charges philosophy in a way that simply discussing them abstractly does not. So I read that book, and I decided that I would like to write fiction, that I wanted to be the kind of person who could write a book like that.

Q: I definitely see that in both your books, but particularly in the new one, A Passage North—Krishan’s very particular lived experience leads to these larger contemplations. Was that the intent?

A: Yeah, but it’s not like I thought to myself, I’m going to fill this book with philosophical discussions. It’s just what I wrote, because it’s what I’m interested in. And because I came to fiction writing in this way, there are certain aspects of novel writing that I don’t pay as much attention to, or give as much time to.

Q: What are some aspects of novel writing that you don’t pay as much attention to?

A: Story. Creating a well-rounded character. Setting. Dialogue. Historical context. I try to pay attention to these things—I do try—but they’re always afterthoughts. A lot of these other things accumulate, they find their place through a process of accretion, and they’re deposited in different waves each time I go through the text. Sometimes things occur to me, and I’m like, Oh, I can just add this. I write over drafts.

There’s no first draft—I have a little center here or a little center there, and then I just go over it, and each time I do, more material accumulates until I find a way to connect those islands into something. I have in my mind that the reader expects the character to be believable or the story to be interesting. I have this little voice in my head that says I need to try—but those elements of novel writing are not what I am interested in.

Q: I had a really great professor who said first draft is intuition, second is intellect. So on your intuitive draft, those elements don’t necessarily come through, but on your intellectual rewriting, they start to come about. Why do you go back and add in those elements, if they don’t interest you?

A: There’s this Buddhist poet, a Sanskrit poet, from, like, the first century. I think his name is Ashvaghosha. In relation to his work, I heard this idea that poetry is supposed to be beautiful, and it’s supposed to be pleasant to hear, because of its aural qualities, and actually, in this sense, poetry is dealing with illusory matters. In a way, it’s appealing to things that distract from what for Buddhists would be the bitter truth of life. And so these poets were called upon to justify why they use poetry—which is, in a way, antithetical to the Buddhist idea that life is suffering—to convey the truth of the Buddha. And the justification that was given was that these poems about the Buddha’s life or about episodes from his life should be understood like pills, like the sugarcoating on the top of a bitter pill, that allows something to be taken in. That feels very simplistic, in some sense, but—

Q: I was struck by the referential nature of this book, and the role that other texts play. Krishan finds a great deal of affective and emotional resonances in texts that are, at first glance, unrelated to the events of his life. I was wondering if that’s similar at all to your reading experience.

A: I think a lot through texts. I often refer to a line or a passage or a moment as a way to explain to somebody how I’m feeling or to refer to something I want to communicate. These moments expand my memory of life. They’re like faint memories that I can always use to compare to my present experience.

Q: This insertion of other texts is so well done. The digressions always make their way around to these very cohesive moments of understanding—it said a lot to me about Krishan, and his reading life.

A: I’m glad you said that, that you feel they were incorporated well—this was a big struggle. Although I do feel a little bit more lukewarm about it now, I did learn a lot about incorporating other materials into my texts through this process. I was interested in the question of tradition, like literary heritage and canonicity. And as an English-language writer, I was trying to think of other canons with which I might align myself.

But the truth is that reading in South Asia is a highly elite activity. Most people have historically been prevented from learning how to read, learning how to write, as part of the caste system—something that continues to this day. Our literary tradition—especially in Sanskrit—is intimately tied to the caste system, and therefore it’s not a tradition that anybody who has been oppressed by the caste system or anybody who doesn’t identify with it can easily affiliate themselves with.

As I understood more—this comes from a period of time when I was trying to learn about non-Western traditions that I might lay claim to—it turned out that I don’t want to lay claim to these texts, because of the way in which they’re located in caste. If I was now interested in canonicity, it would have less to do with a South Asian canon than specifically a Tamil canon.

Q: There’s no dialogue in this new book. Did that come about organically? Or was it a conscious craft choice from the start?

A: I was aware from the start that the text was not going to have dialogue. There are two things I could give you as an explanation for that. One is that the question of why I am writing in English is always there for me. Rather, I mean that the issue of my not writing in Tamil is always present, and I think that makes especially salient the absurdity of putting English words into Tamil mouths.

All the conversations in A Passage North are in Tamil—except for the ones that Anjum has with Krishan, every other relationship occurs in Tamil. What I simply chose to do is no dialogue, or to report the dialogue. So one thing I could say is that I avoid doing it because I don’t want to be engaging in ventriloquism. The other reason I might give, or I might have given at some point in the past, has to do with simply not being interested in what people say to each other. I no longer believe that, though.

There are moments of conversation in which people reveal themselves, and they’re often moments that have a kind of confessional quality, in which a truth is spoken. It’s not so much about a truth being spoken but about a conversation that takes place in the mode of speaking the truth. That occurs very rarely between people, and often requires different kinds of conditions, a different kind of extremity. So much of conversation is about eliding certain things, posturing in certain ways, concealing various things, manipulating another person a certain way, angling of certain kinds. And I don’t have the patience as a writer to look for the truth of a person in the silences or the gaps or the contradictions. That requires a lot of patience that, unfortunately, I don’t have.

Q: You’re an impatient writer, you would say?

A: Yeah.

Q: How so? Aside from not writing dialogue.

A: See, I read for very specific reasons—I read to know how things are, like in the way that one would read the Bible. It’s as if I view books as spaces in which only certain kinds of moods are to be inhabited.

I am very petty, for example—I can be very small-minded, and I have small-minded and petty friends as well. It’s not that I avoid pettiness, or judge people for pettiness, but it’s something that I will not accept in a book. Maybe it has to do with coming from a context in which books are not readily available and when you see a book, you believe it’s something that has to be valued. And, therefore, if somebody’s an author, they cannot be lighthearted or flippant people, they cannot be petty.

For whatever reason, the object of a book is very important to me, and for me it’s not a place to be lighthearted. I’m very impatient about any book I read or any book I write getting to the question of what life is like and not tarrying on more frivolous matters.

Q: Does that make you an impatient reader or an impatient writer?

A: Both, I would say.

Courtesy: The Paris Review

SL novelist Anuk Arudpragasam selected as a recipient for 2021 Booker Prize

Sri Lankan Tamil novelist Anuk Arudpragasam, has been selected as a recipient for this year’s Booker Prize.

The novelist studied philosophy in the United States, receiving a doctorate at Columbia University. His first novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage, was translated into seven languages, won the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, and was shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize.

The 13 books on this year’s longlist were chosen by the 2021 judging panel consisting of historian Maya Jasanoff (chair), writer and editor Horatia Harrod, actor Natascha McElhone, twice Booker-shortlisted novelist and professor Chigozie Obioma; and writer and former Archbishop Rowan Williams.

The list was chosen from 158 novels published in the UK or Ireland between October 1, 2020 and September 30, 2021. The Booker Prize for Fiction is open to works by writers of any nationality, written in English and published in the UK or Ireland.

The 2021 longlist, or ‘The Booker Dozen’

- A Passage North, Anuk Arudpragasam (Granta Books, Granta Publications)

- Second Place, Rachel Cusk, (Faber)

- The Promise, Damon Galgut, (Chatto & Windus, Vintage, PRH)

- The Sweetness of Water, Nathan Harris (Tinder Press, Headline, Hachette Book Group)

- Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishiguro (Faber)

- An Island, Karen Jennings (Holland House Books)

- A Town Called Solace, Mary Lawson (Chatto & Windus, Vintage, PRH)

- No One is Talking About This, Patricia Lockwood (Bloomsbury Circus, Bloomsbury Publishing)

- The Fortune Men, Nadifa Mohamed (Viking, Penguin General, PRH)

- Bewilderment, Richard Powers (Hutchinson Heinemann, PRH)

- China Room, Sunjeev Sahota (Harvill Secker, Vintage, PRH)

- Great Circle, Maggie Shipstead (Doubleday, Transworld Publishers, PRH)

- Light Perpetual, Francis Spufford (Faber)