Between romance and revolution: Nanda Malini and Politics of Pavana-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

Nanda Malini has a great deal to do with my being a Sri Lankan. How could one grow up here and not hear that voice? Nearly every radio station plays it every hour or so; unless you turn the radio off, you can’t escape her. Even then her voice creeps up somewhere. Ever ubiquitous, she makes herself heard in the most unpredictable moments.

As with Victor Ratnayake, everything she has sung has become so embedded in our collective consciousness that we can’t ignore it. This has mostly been on account of how she has brought two diametrically opposed themes, love and politics, together. If it’s hard to talk about either without remembering a line from her songs, it’s because she’s made the transition from love to revolution so seamlessly that there’s really no other artiste from here who can compare. Such an achievement should not be belittled: in the history of the Sinhala song, I find it difficult to think of a singer who’s engaged with the worldly and the political as much as Malini did.

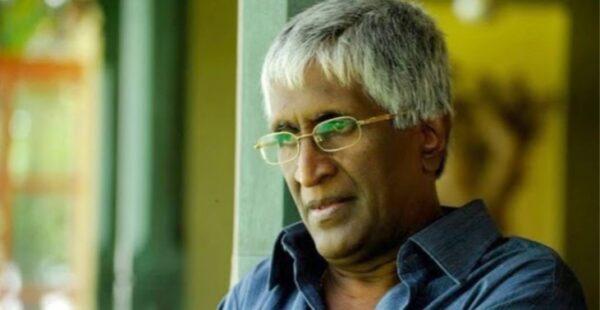

When reflecting on Nanda Malini’s political forays in the 1970s, it’s impossible not to mention Sunil Ariyaratne. Most of Malini’s politically assertive songs were penned by Ariyaratne. He was her principal lyricist in Pavana, the most politically explicit of her albums. His involvement with her career of course preceded Pavana: their first collaboration was perhaps Sakura Mal Pipila, a song which was banned by authorities for its perceived anti-establishment content. Malini’s and Ariyaratne’s political interventions hence predate Pavana, even if we primarily focus on the latter when writing on those interventions. In that sense their first political album was Sathyaye Geethaya, which is not unabashedly political in the way her later work would be. Yet in this, as in their later work, Ariyaratne served as her kivindune.

It’s hard to sum up Pavana’s impact without having lived through the times in which it first came out. For my parents’ generation, it represented a diversion and an aberration on the part of their favourite woman singer. For the more radicalised, it represented the fulfilment of their hopes: a songstress who captured their angst in ways no other vocalist – barring one, who I will get to later in this essay – had. In works like this it’s obviously futile to separate the singer from the poet: what part was Malini’s, what part Ariyaratne’s? But despite the spirit of collaboration that enlivened it, Pavana remained a distinctly Nanda Malini product. The lyrics did not become peripheral or take a backseat; far from it. Yet for much of the country, the face of the performer became more important than the name of her versifier.

What I am saying, essentially, is that Pavana would not have worked with another singer. In saying this, of course, I am by no means suggesting that there were no other radical artists and writers in the country then. Yet far more than her contemporaries, Malini epitomised the times she was in and of. Donning a white sari wholly at odds with the politics she espoused, she cut an incongruous figure: a woman who had sung of romance, now singing of revolution. The turnaround was sharp and definite: she would have nothing to do with the romanticism of her early years. Like Gunadasa Amarasekara critiquing the influence of the Peradeniya School on his novels in Aliya Saha Andayo, she emerged a different person. In Amarasekara’s case, the self-critique turned him to the politics of nationalism; in Malini’s case, it turned her to the spirit of politics. It naturally goes without saying then that in post-1980 Sri Lanka, these two epitomised the confluence of art and politics far more than anyone else did, or could.

That has as much to do with the artiste as it does with the album. Pavana was unprecedented and unique: nothing prepared audiences for it, and nothing followed from it. What stood out in it? Why made it so unique? Why did it peter out after a while?

Pavana became so unique on account of Nanda Malini’s voice. Sardonic and acerbic, that voice had a way of striking you. Even in her earlier phase, when she sang of love, she laced her sense of wonderment with a veneer of raw candour; hearing Sari Podiththak now, for instance, I am intrigued by how the verses veer between the natural simplicity of the theme and the layers of meaning the vocalist infuses into it. The song centres on a family trying to marry their daughter off and the travails of finding a suitable groom. Yet, from the narrator’s perspective, the whole process of visiting one suitor to another comes off as tumultuous, hilarious: worthier of parody than of the hallowed respect marriage commands in traditional Sinhala society. It is this kind of sardonic joi de vivre which animates Sakura Mal Pipila: sakura flowers blooming in the open, the sun up at night, the sky falling down, and lions transforming into winged beasts. She revels in chaos, in disarray, thereby flaunting her rebelliousness against convention.

What interest me most in Pavana are the songs with which she seems to summon this phase in her career. In these songs, she doesn’t so much turn to and embrace radicalism as she rejects, ridicules, and flouts convention. Malini’s voice is so distinct here because you are never sure whether she’s being sincere or sarcastic, whether she’s presenting things as they seem or laying bare the hypocrisy and reality lingering beneath the surface; it takes a second reading of these lyrics to discern the irony underscoring them. There are very few songs in Pavana which project this irony, but the few that do (like Upasakamma) are the ones that stand out.

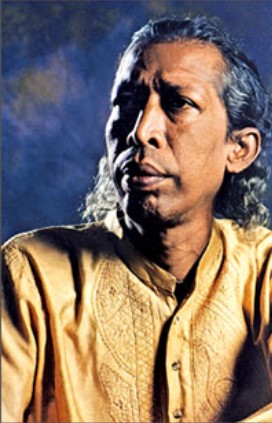

These songs should be contrasted with those of that other great, radicalised artiste of her time, Gunadasa Kapuge. The two were contemporaries; both adroitly used music to articulate their respective politics. And yet, striking as the comparison may seem, there is less a similarity than a difference between their output. The point of Nanda Malini’s politics, at least in Pavana, was to direct the seeing anger of a dominated milieu against a dominating class. There is anger and sadness, but they are cloaked by a joyous defiance. Indeed, barring a song or two, she does not bother revealing the falsities of tradition. She lets out her feelings, but there is a sense of bitter candour in the lyrics that refuses to reflect on false impressions. In Pavana, then, far more than in any other political songs, the lyrics let the polemical win over the poetic.

Even at his most assertive, Kapuge did not take this route. There is, in “Sudu Nanda”, “Ahasa Usata”, and “Uthuru Kone”, an attempt at retaining the poetry in the polemic. These are not really songs of love; “Sudu Nenda” is, but what strikes one in that song is not the lover’s lament, but the class difference between the narrator and his lover that feeds his lament. In “Ahasa Usata” the narrator is almost bemused at how those who work on big construction projects go higher than anyone else; just not in their class position. “Uthuru Kone” is different from Malini’s “Mongoliyanuwane”, in that unlike the latter it does not resort to the rhetoric of war. Malini’s (and Ariyaratne’s) aim in “Mongoliyanuwane”, “Budun Daham”, and “Mugurak Awasi Thana Mugurak”, hence, is to raise the battle cry. More often than not they give into an insularity of vision; in “Budun Daham”, for instance, the cosmopolitanism of their worldview – their vision for the country – is contradicted by an almost bigoted rage at the nation of “hota bariyo“, India. This is a contradiction Kapuge never had to work with, nor resolve.

Even at his most assertive, Kapuge did not take this route. There is, in “Sudu Nanda”, “Ahasa Usata”, and “Uthuru Kone”, an attempt at retaining the poetry in the polemic. These are not really songs of love; “Sudu Nenda” is, but what strikes one in that song is not the lover’s lament, but the class difference between the narrator and his lover that feeds his lament. In “Ahasa Usata” the narrator is almost bemused at how those who work on big construction projects go higher than anyone else; just not in their class position. “Uthuru Kone” is different from Malini’s “Mongoliyanuwane”, in that unlike the latter it does not resort to the rhetoric of war. Malini’s (and Ariyaratne’s) aim in “Mongoliyanuwane”, “Budun Daham”, and “Mugurak Awasi Thana Mugurak”, hence, is to raise the battle cry. More often than not they give into an insularity of vision; in “Budun Daham”, for instance, the cosmopolitanism of their worldview – their vision for the country – is contradicted by an almost bigoted rage at the nation of “hota bariyo“, India. This is a contradiction Kapuge never had to work with, nor resolve.

Insofar as these constitute a critique of Pavana, the critique can help us understand why Pavana failed to sustain momentum after its peak at the height of the bheeshanaya. I don’t necessarily agree with Malinda Seneviratne’s view that it was the political explicitness of these songs which limited their appeal. To say that is to say that “La Marseillaise” is pertinent to only 1792, or that “The International” is pertinent to only the late 19th century. Talking with Malinda many years ago, Malini disagreed with such an assertion, and argued that tethered to its period as it would have been, the issues which Pavana spoke about were “still valid.” I agree: hardly anyone who has listened to “Yadamin Banda”, “Seethala Polawa”, or “Avurudu Dedahas Panseeya Wasarak” will find it difficult to transpose their themes to a contemporary context.

The more valid critique, or criticism, of Pavana is that the lyrics of these songs do not match up to the subtlety which once animated Malini’s (and Ariyaratne’s) collaborations. When I listen to “Perahera Enawa”, I discern an almost delicious joi de vivre at work, a musical sensibility tearing to pieces the falseness of surfaces: Malini first outlines the hallowed pomp and pageantry of a perahera before revealing its underside. Pavana doesn’t contain this sensibility. It may be that the directness of its subject matter made the songstress and kavidune prefer the explicit to the ironic. But we have the example of Kapuge’s work to remind us that political objets d’art do not necessarily have to compromise on subtlety to gain in power and strength. Perhaps due to this, the politics in Pavana comes off as crass, divisive, hardly life-affirming; by comparison the songs in Sathyaye Geethaya feel more subtle, more open-ended, and much less divisive.

It is no doubt both a confirmation of this critique and a tribute to the singer, her lyricist, and the album that Pavana was never followed by a comparable endeavour. In the 35 years or so that have passed since it debuted, Pavana continues to stand as the most politically explicit musical work Sri Lanka has ever produced; in its blend of popular and folk music, of baila and poetry, it gave the radicalised an antidote to their grievances. The government of the day saw it fit to not just ban Pavana cassettes, but also arrest anyone caught possessing them. It is a testament to its enduring popularity and also its limited appeal that there has never been a Pavana since it dissipated in the years following the bheeshanaya. Kapuge did come close, with Kampana. But Kapuge’s sensibility was qualitatively different. In the great pantheon of vocalists and lyricists, Nanda Malini and Sunil Ariyaratne thus continue to occupy high places.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com