Neville Weereratne: the Artist and his Distant Homeland – by Tony Donaldson

The first page of Cradle Songs published in the Ceylon Observer Pictorial in 1967 with illustrations by Neville Weereratne.

by Tony Donaldson

This essay on the life and art of Neville Weereratne is based on interviews recorded in Melbourne in July 2014 and from material collected during fieldwork in Australia and Sri Lanka.

The artist and author Neville Weereratne died in Melbourne on 3 January 2018 at the age of 86. He was born in Colombo on 3 December 1931. A Sinhalese by descent and the youngest of five siblings, he began drawing at about the age of six. He grew up in a Roman Catholic family in Hulftsdorp, near to the Supreme and Magistrate courts, but their home was requisitioned by the civil authorities in World War 2 and so the family moved into a house in Dehiwela owned by the Peries family (Ivan and Lester).

Neville was educated at St Joseph’s College in Colombo and was one of Richard Gabriel’s first students when he began teaching art at the school in 1945. Richard was 21 and Neville 13 when they first met and as their understanding of each other grew, they soon became lifelong friends.

In 1949, Neville began teaching art at St Peter’s College. He spent the next year serving an apprenticeship with Ivan Peries – a founder member of the ‘43 Group who had also taught Richard Gabriel. Neville learnt the mechanics of painting from Ivan by assisting him on any task such as cleaning his brushes and palette or stretching his canvas.

As a Catholic and a teacher at St Peter’s College, his associations were mainly with priests and as their discussions were about theology and styles of living, he became attracted to monasticism and to the idea of living a quiet modest life devoted to work, study and prayer in a religious community. He went in search of it, and seeking a stricter form of monastic life, in 1951 he entered the Caldey Abbey – a monastery of the Cistercian Order on Caldey Island off the south coast of Wales. Here, on this “cold and miserable island” as he once described it, he pursued the spiritual life of prayer and contemplation.

However, the daily routine and strictness of the Abbey didn’t suit his temperament. Feeling uneasy and out of place, he left the monastery after six months and went to London to study drawing at the Chelsea School of Arts. But he didn’t like the school and after three months he left to team up with Ranjit Fernando, to help organize exhibitions for the ‘43 Group in London and Paris. Neville joined the ‘43 Group in 1952 and exhibited with them in London, and continued to exhibit his paintings with the group until 1960.

Though he enjoyed his life in London, Neville was persuaded by his father to return to Sri Lanka in 1953 after he threatened to cut off his weekly £10 allowance. He returned to teaching art at St Peter’s College but found the education system tedious and quit in 1955. He was then invited by Denzil Peiris, the editor of the Silumina, to join the newspaper as an illustrator. The two had met earlier at St Joseph’s College when Denzil came to judge a music competition.

Neville also worked as a Cartographer for Jana – a fortnightly news magazine on Southeast Asian politics, before moving into mainstream English newspapers. From 1954 to 1959, he worked as a Subeditor for the Ceylon Daily News. He moved to the Sunday Observer in 1960 working as a Subeditor (features editor). He also designed posters for the film Sandeshaya (1959) which was directed by Lester James Peries with one of its principal actors being Neville’s good friend Arthur Van Langenburg.

Neville and Sybil Keyt married on 6 June 1959 after the two had met at the Cora Abraham art school, which was established in 1949 by Mrs Cora Abraham as a school dedicated to children as artists. Out of the school came a gathering of senior students into what came to be known as The Young Artists Group which shared similar attitudes and ideas to the ‘43 Group. Among its early members were Noeline Fernando, Sybil Keyt, Laki Senanayake and Mike Anthonisz.

After leaving the Sunday Observer in 1966, Neville and Sybil planned to migrate to Australia to be nearer to her family in Melbourne but they changed their minds after J. R. Jayewardene persuaded Neville to take up a position at the Ceylon Tourist Board as Editor for Tourist Publications – a position he held from 1967 to 1971. His job was to put together publicity folders, brochures and posters, and to produce films and entertain visiting journalists from abroad. He didn’t get the opportunity to travel around Sri Lanka as much as he should have working for the Ceylon Tourist Board, but one memorable trip took place when he and Sybil travelled with the photographer Pat Decker to the north of the country. They travelled through the west coast to Jaffna and then came down through the middle of the island to areas Neville had not seen before.

His illustrations during this period included a delightful set of drawings featured in a setting of four songs titled “Cradle songs” by the Sinhala folk music specialist W. B. Makulloluwa, which was published in the Ceylon Observer Pictorial in 1967.

In 1971, as a Marxist revolution was fermenting in the south of the island, Neville and Sybil decided to migrate to Australia. He talked about their decision to leave Sri Lanka in an interview recorded in 2014. “Things were going from bad to worse. There was a vicious revolution in the south. Life was very tentative. The atmosphere was disastrous and so we felt it was a good reason to return our original idea to come to Australia and meet Sybil’s family in Melbourne.”

After relocating to Melbourne in October 1971, Neville began working as a Subeditor for a girlie magazine in South Yarra called the Postscript Weekender – a job he described as “fun and games, but absolutely essential as a bread-and-butter job.” He then spent a year as a Subeditor on The Sun at The Herald and Weekly Times, but was then offered a job as a Subeditor for The Advocate – the weekly newspaper of the Catholic Archdiocese of Melbourne. He took to it with glee and worked there from 1977 to 1979. He then worked as an Information Officer for the Caulfield Institute of Technology until 1982 when he was recalled to The Advocate to be its editor – a position he held until 1989 when he retired and returned to his passion of drawing and painting.

This was also the time he spent writing about the Sri Lankan arts. He was an authority on the ‘43 Group which came from direct personal experience as a member of the group, but he also had a wide knowledge of many artists in postcolonial Sri Lanka. His publications include: 43 Group: A chronicle of fifty years in the art of Sri Lanka (1993), The Art of Richard Gabriel (1999), Visions of an Island – Rare works from Sri Lanka in the Christopher Ondaatje collection (1999), George Beven: a life in art (2004), The Sculpture of Tissa Ranasinghe (2013), and The Artist in Every Child: the Legacy of Cora Abraham (2015). He authored an essay on Justin Daraniyagala and edited several books including Applause at the Wendt (2003).

Curiously, he never wrote an autobiography and though he took great care in researching and documenting Sri Lankan artists in his books, he didn’t publish anything about his own art practice. Modesty may have prevented him from doing so and a critical appraisal of his life and work falls to a new generation of art writers.

Why did Neville choose certain subjects for his paintings and not others? Though his life at the Caldey Abbey in Wales was independent of his art, it may explain his attitudes, feeling and reactions to different situations in his life as an artist. For instance, his experience at the monastery may explain why he never painted religious subjects like his guru Richard Gabriel. But for all their differences, the two artists tackled similar subjects in their experiments with colour and simplified compositions to capture human experiences as a constituent of the Sri Lankan landscape. Neville drew subjects from everyday experiences – fruit sellers, village girls, lovers, outrigger canoes, musicians, dancers, and family scenes. He was attracted to water pots, stray dogs and Buddhist monks because they were so much a part of the Sri Lankan landscape that he found it impossible to avoid these subjects in his art.

He preferred to work in oils because he it could manipulate it better than acrylic or watercolour. The forms of his paintings were organized against the sea or landscape backgrounds in a range of strong bold colours to evoke the light and textures of the tropics, especially yellow, orange, blue, brown and green. It was his trademark. But it was his ability to inject certain moods, feelings and emotions into a canvas that gave his paintings a distinctive identity. Painting, according to Neville, was about human relationships rather than the individual. For example, the oil painting titled The Lovers (2014) depicts a kind of relationship commonly found in Sri Lanka between a woman and her man, particularly her subservience to him.

A different kind of relationship is portrayed in Girls with Water Pots (2012) in which two friends rest after collecting water from a well. In The Bathers (2014), a woman stands holding a water pot while her friend sits straightening her hair after washing it. The faces of the two women have few details and though the figures could be anybody, a viewer can still sense a few clues about their relationship.

Neville sometimes left the faces blank in a painting. When asked why he did so he replied: “Because I don’t know who they are.” He didn’t paint specific people. The figures could be of any Sri Lankan but

Another aspect of his visual language was to combine elements of the physical and metaphysical worlds. In one of his more complicated paintings called The Farewell (2011), a Sinhalese fisherman bids goodbye to his wife before going out to sea which is expressed through their physical embrace.

However, the Sinhalese are by nature reticent and do not indulge in public displays of affection as depicted in this painting, even though the fisherman and his wife must have felt it in their heart. The painting goes beyond the physical world to capture the inner feelings of the heart.

In Tambapani (1968), which depicts a scene on a Sri Lankan beach, the physical world is conveyed through everyday subjects such as the water pot, stray dog, outrigger canoe, and a man sitting on the beach wearing a sarong. These are combined with subjects that do not belong to the physical world in Sri Lanka such as the two embracing lovers and nude female figure, which we would not expect to see on a beach in Sri Lanka. One interpretation of the painting is to see the elements representing the physical world such as the water pot, stray dog and outrigger canoe acting as a catalyst with the embracing lovers and nude figures thus enabling a viewer to roam the spaces between the physical and metaphysical worlds.

Because his emphasis was on these elements as well as human relationships, his approach to nudes was not about excavating the human anatomy so a viewer could feel the flesh on the canvas or the blood pounding behind the flesh. His nudes were unobtrusive as he didn’t inject anatomical detail into the figures probably because it didn’t suit his visual language.

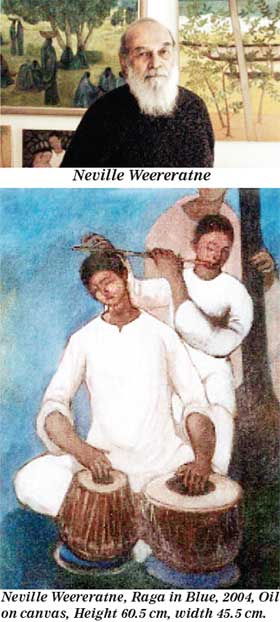

A great love he shared with his artist-wife Sybil Keyt were Indian subjects. Sybil was especially passionate about India as she told The Sunday Times features editor and writer Renuka Sadanandan in 2010: “I love India, have a soft spot for it.” Sybil produced evocative paintings of India as in South Indian Landscape (1993) Rajasthani Women (1999) Sunset over Rajasthan (2002) The Golden Mosque (2002) Moghul Entrance (2004), and The Pink Palace (2007). While Neville retained a Sri Lankan worldview in his art, he did sometimes chose Indian subjects for his paintings as in Krishna and the Gopis (1993), Veena player (1999), Idyll: Radha and Krishna (2007), and Raga in Blue (2004) which captures the serene mood of three musicians performing a raga.

The opening of a Sybil Keyt and Neville Weereratne exhibition attracted great interest in Colombo. All kinds of people came to their shows organized by Nazreen and Dominic Sansoni – the directors of the Barefoot Gallery – including Sumitra and Lester James Peries, Rohan de Soysa, Selvam Canagaratna, Laki Senanayake and Kushan Manjusri, to name a few. There were also journalist friends such as Nihal Ratnaike who wrote of Sybil and Neville in a 2004 catalogue: “These are painters with a serious respect for their art. What is more, they can draw… [their artworks are] lucid projections of felt and understood images…”

While Neville lived in Australia for 46 years and established roots in Melbourne with his wife and family, as with the monastery in Wales, he rejected Australia as a subject for his art because he had no feeling for it. By contrast, Sybil did find inspiration in Australia and included it as a subject in her paintings. But living in Australia for Neville seemed to strengthen his imagination and a desire to understand his distant homeland through his art, as he explained in an interview recorded in 2014.

“Having lived in Australia since 1971, I am now much more conscious of what Sri Lanka has to offer than I was when I lived there. I can see the culture it represents, its capabilities, and what it has achieved it in a disinterested way. These things seen at a distance are clearer to me than when I was close to it living in Sri Lanka and then I didn’t notice it. But now I can see it anew and I can appreciate and enjoy it much more than when I was in Sri Lanka over 40 years ago, though it is the same country that engaged my mind as a painter from the beginning.”

The sculptor Tissa Ranasinghe put it differently when he wrote of Sybil and Neville in a Foreword to a catalogue published by the Barefoot Gallery in 2002: “The point of connection and continuity in their paintings in the recurring themes is the shared love of the people and places they left behind and images that haunt them and for which they ache.”

Outside of art, Neville enjoyed listening to classical music. He was a keen stamp collector and fond of aquariums and fish. Both Sybil and Neville were avid readers and together the two acquired a vast library of books. As one might expect, Sybil and Neville were keen followers of Indian and Sri Lankan writers. One section of their library was devoted entirely to India with books by Shashi Tharoor The Great Indian Novel and Show Business; Khushwant Singh I Shall Not Hear the Nightingale, Train to Pakistan, The Company of Women, Big Book of Malice, and Not a Nice Man to Know; Shona Ramaya Flute; Ellis Peters Mourning Raga; Kunal Basu The Miniaturist; and Edward C. Dimock Jr. and Denise Levertov In Praise of Krishna: Songs from the Bengali.

Neville Weereratne’s contribution to Sri Lankan art through his paintings and publications is a significant legacy that will benefit art historians and scholars for a long time. His writings on the ‘43 Group have left us with a unique authoritative record of this visionary group of artists that was active through the colonial and postcolonial years in Sri Lanka from 1943 to 1960.

© Tony Donaldson, 2018.

Victor Melder

Sri Lanka Library

No Comments