The Ceylon Journal III: A Review-By Dhanuka Bandara

Source:Dailymirror

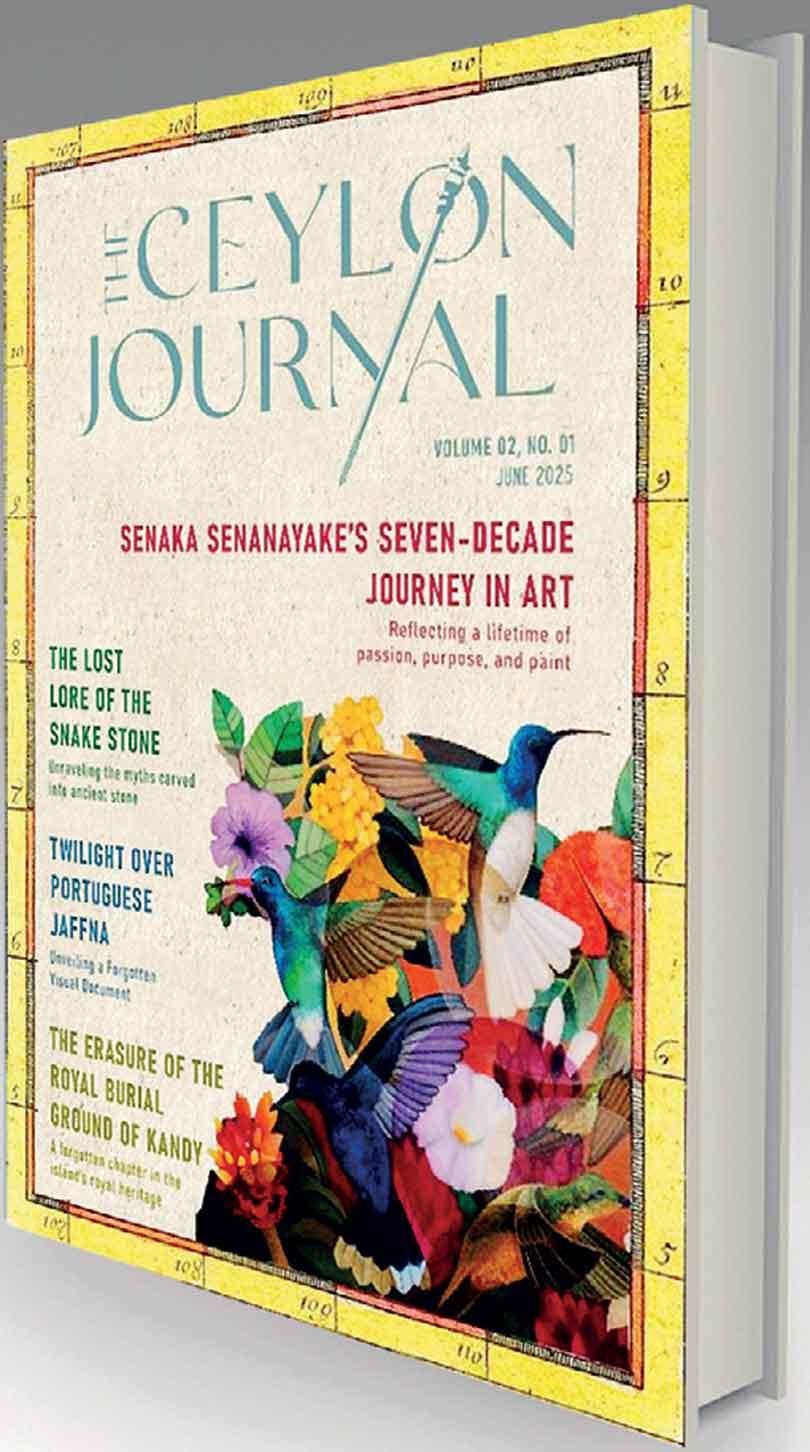

The third installation of the bi-annual periodical The Ceylon Journal certainly continues the success of the two previous issues. Edited by Avishka Mario Senewiratne, The Ceylon Journal was first launched in July 2024. This unique journal, which in turn draws inspiration from Young Ceylon, a 19th-century Sri Lankan journal published by Charles Lorenz Ambrose and his friends, continues to publish immensely readable, yet well-researched and informative articles on a wide range of topics.

The third volume of The Ceylon Journal is dedicated to Alexander Johnston, an “orientalist” scholar and colonial administrator. What The Ceylon Journal reminds us of is that history is a complicated affair. While it has become fashionable in liberal academia to understand the colonial period as exclusively oppressive and destructive, many of the articles in The Ceylon Journal take a more dispassionate approach to interpreting and understanding Sri Lanka’s colonial past. The latest issue of the journal (Volume II No. 1, as it goes into a new year) opens with an article on Alexander Johnston—Ceylon’s third chief justice and scholar—by Avishka Senewiratne. Johnston was born in Scotland and came from aristocratic roots. Senewiratne claims that he was proficient in multiple “native” languages such as Tamil, Telugu, and Hindustani. Senewiratne portrays Johnson as a “liberal” reformer who sought to align “British laws with local customs and values”. Johnston was also a scholar, and Senewiratne points out that he was one of the earliest Brits to cultivate a serious interest in Buddhism; his role in bringing Sri Lankan historical chronicles, Mahavamsa and Rajavaliya to the attention of Western readership is also noted. Thus, despite being a colonial administrator and, as such, in the final analysis, always a loyal servant to the British crown, Johnson’s contribution to reviving native culture, especially at this early stage of British colonial rule, seems significant. The journal also includes a commentary by K. D. Paranavitana on Johnston’s census of the Dutch and Burgher inhabitants of Colombo circa 1809. Figures such as Johnston and, for that matter, Ambrose, despite their colonial affiliations, were cosmopolitan and multiculturalist. They were in many ways instrumental in the emergence of Sri Lankan nationalism later in the 19th century and the early 20th century. Thus, The Ceylon Journal illustrates that colonialism contained the seeds of its own destruction. While on the one hand it was a coercive force that held the island in the thrall of the British Empire, on the other hand, it would also pave the way for decolonisation, conforming to a particular Hegelian, if not natural law.

“The Kandyan Ambassadors in Colombo: Jan Brandes’s Artistic Chronicle” by Nilantha Perera Palihawadana brings to attention the “dialogic” nature of colonialism. The article is a commentary on Kandyan ambassadors from the court of Rajadhi Rajasinghe visiting the Dutch governor in 1772. Despite the popular conception of the colonial conquest as a series of unending, bloody battles, this article shows that colonisers and the natives also, on occasion, had cordial and diplomatic relations. The article records the great pomp with which the Kandyan ambassadors were welcomed: “As the carriage passed through the gate, the ambassadors were honoured with a thunderous volley of cannon salutes from the ramparts”. Despite the warm welcome, the demands of the Kandyan ambassadors were seldom taken seriously (such as the demand to return the coastal lands to the Kandyan king). Thus, these meetings seem to have had a largely performative function, in some ways calculated to appease the locals rather than address their concerns.

One of the great strengths of The Ceylon Journal is bringing hitherto unknown or forgotten historical material/facts to attention. “The Fall of Portuguese Jaffna in a Rediscovered Visual Document” is focused on the advent of Dutch power in the island. The article is a study of a recently discovered manuscript map showing the siege of Jaffna by the Dutch invaders. The fact that the Dutch fought off the Portuguese at the invitation of Rajasinghe II, the King of Kandy, is well-known. The Dutch double-crossed the King and refused to return the coastal areas that were recaptured; an event that has been immortalised in the Sinhala proverb, “trading ginger for chillies”. What this episode in history yet again illustrates is that colonialism was not one-dimensional, one-way process; that the native agency was often involved in negotiating with the colonial powers, although the final result was complete capitulation. The article, drawing on the map, provides a fascinating account of the capture of Jaffna by the Dutch East India Company. Given that the map was recently discovered, it is possible that this is the first time this map has gained scholarly attention and been introduced to the wider readership. While different in focus, “The Fisherwoman of Karainagar” by Anisha L. Russo looks at a marginalised community in the Jaffna peninsula. This article, more anthropological than historical in approach, makes a strong argument, stressing the agency of women involved in the fishing trade in Karainagar, an island off mainland Jaffna, and highlights their contribution to the wider economy and social cohesion of Karainagar. “The Production and Trade of Ceylon Gems in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”, by the noted Peradeniya historian C.R. de Silva, is a commentary on the changing fortunes of the gem trade around the time of the advent of Portuguese power in Sri Lanka. This article sheds light on an often neglected, if not forgotten, area of Sri Lankan colonial history.

“Damnatio Memoriae – the Erasure of the Royal Burial Ground in Kandy” by Buddika Dassanayake is important reading for anybody who is interested in the history of the Kandyan kingdom. Perhaps this article ought to be read in tandem with Manohara de Silva’s ‘The Kandyan Convention (1815): A Treaty Marred by Controversy” in the previous volume of The Ceylon Journal. With the publication of Gananath Obeyesekere’s Many Facets of the Kandyan Kingdom and The Doomed King, there appears to be a renewed interest in the Kandyan period. Obeyesekere, in his revisionist work, casts the much-maligned last king of Kandy, Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe, in a more positive light than folklore and traditional historiography. The articles on the Kandyan period in The Ceylon Journal further widen the understanding of the Kandyan period, which is often thought of as a period of decadence and decline compared to the supposed heyday of Sri Lankan civilisation during the Anuradhapura period. Dissanayake’s article sheds light on the now little-known Royal Burial Grounds of Kandy, which were destroyed following the colonial conquest of Kandy. By unearthing suppressed narratives of colonial violence such as this, The Ceylon Journal significantly contributes to the study of Sri Lankan history. Reverting back to an earlier period, “The Archaeology of Lanka’s Early Urban Centres” by Chryshane Mendis, is one of the more technical articles in the journal. The article highlights the astonishing endurance of the Anuradhapura period, which lasted nearly 1500 years. Mendis argues that there is much yet to be uncovered and studied. As the author notes, even the location of the royal palace, if such a place indeed existed, is still unknown. The article highlights that despite the prominent place that the Anuradhapura occupies in the national historiography and imaginary, there is much that is unknown and remains to be discovered about this period.

Even though the primary focus of The Ceylon Journal is history, it contains an eclectic selection of articles which are no doubt of interest to the general readership. The latest journal contains two insightful pieces on the history of Sri Lankan education. “Clara Motwani: An Illustrious American Educator of Sri Lanka” by Goolbai Gunasekara pays homage to Clara Motwani, an American theosophist who played a key role in promoting women’s education in the early decades of the 20th century. Even though Motwani herself had a convent education, she headed prestigious Buddhist women’s schools such as Visakha Vidyalaya and Musaeus College, Colombo. While this article is anecdotal in nature, it is nevertheless a promising starting point for a more critical and academic engagement with Motwani’s contribution to Sri Lankan education. “A Brief Survey of the Evolution of Visual Art Education in Ceylon, c.1840-1950” by Priyantha Udagedara maps the early developments of Sri Lankan visual arts education, from its colonial roots to developing a truly “national” artistic idiom in the 20th century. While broad and general in nature, the article is likely to benefit the uninitiated and even the specialist, too, as it records minutiae about early pioneers of Sri Lankan visual art (in the colonial period), such as J.L.K. Van Dort and A.C.G.S. Amarasekara, who are not necessarily well-known today. This article could be read alongside, and perhaps as the prequel to, “Pioneers of Modern Expression: Unveiling the Artistic Legacy of the ’43 Group of Ceylon” by Nilantha Palihawadana, which was published in the inaugural edition of The Ceylon Journal.

It is heartening to see how The Ceylon Journal has become a venue for the specialist and generalist alike. Its jargon-free, thorough, and well-written articles make for great reading. Given the interest that it has generated already and the calibre of writers it has attracted, the future of this journal seems to be promising.

Copies of the latest issue can be reserved and purchased by calling +94 72 583 0728