Golden Jubilee years of Sinhala Pop Music;-By Dr D.Chandraratna

Christian youth herald an Integrative revolution

Source:Island

Right at the outset I need to justify the above subtitle. The readers may be understandably perturbed that the use of the word Christian is an irrelevant identity marker, given the violence that identity markers have caused in Sri Lanka. I am acutely conscious of Amartya Sen’s advice, ‘Reason before Identity’ before we classify groups (Identity Violence, 2007). However this identity profiling is only an empirical generalization contextualized here because it has contingent social significance.

I wish to demonstrate how young, predominantly Christian youth, through Sinhala song stumbled on to foster amity, dialogue and communication between communities, ‘unloading a million bricks’ out of the Sinhala psyche (Langston Hughes, The Big Sea, 1986). Having relieved my burden I shall come to the subject proper. This article is to celebrate more than half a century of the continued dominance of Christian youth led popular Sinhala music where they reigned supreme.

Bands Galore

At independence while Sinhala music was experimenting with different forms, amidst debate and rancour the city dwelling youth were emulating the sprouting bands and vocalists in the West, and Latin America. The Beatles, Shadows, Kinks, Rolling Stones etc. and generally fast rhythm music was mimicked by the westernized youth who were mostly Christian whose talents were honed in the arts and performances of the church. The bill was split between competing groups. Among the most popular were La Ceylonians, Moonstones, Sunflowers, La Lavinians, Los Flamingos, Hummingbirds, La Bambas, Los Muchachos, Los Serenaders, Los Caberellos, Beacons, Peddlers, Sunflowers, Spitfires, Gypsies, Eranga and Priyanga and many more in the country towns including the North. The Christian schools in Colombo as St Thomas’, St Peter’s, St Joseph’s, St Benedict’s provided much needed youth to work the bands. Likewise the Christian Schools in towns of Kandy, Ratnapura, Nawalapitiya, Galle, and Jaffna followed suit supplying vocalists and instrumentalists.

The dawn of the ‘people’s revolution’ in the late fifties was turbulent. It was a time Sri Lankan society was badly challenged by language and religion thereby partitioning the pluralities and diversities that were considered the norm. The revolution was executed in a rush without debate and dialogue. Exultation was short lived and as the ideals became distant many communities felt betrayed and perceived to feel outside the Sri Lankan heritage. The thesis canvassed here is that Sinhala popular music championed by Christian youth, led an integrative revolution, which was successful in no small measure.

The sudden loss of the conviviality and robust richness of the cultural mix that was their world may have driven the youth to yearn for a mechanism to return to the beautiful old days. Sinhala pop music beckoned them as the integrative solution that many were yearning for. Their school education, mainly in the liberal arts, equipped them with a number of competencies; an intellectual tolerance, substantial questioning of dogmatism, social maturity, rejection of authoritarianism and a degree of secularizati

on outside of books. They were not oblivious to many aspects of the contemporary world.

Meteoric popularity of the Sinhala bands

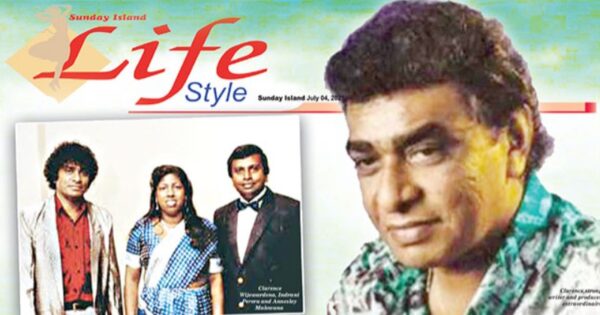

With apologies to many bands and artists of yore including the Dharmaratna brothers who were the stars of the Sinhala pop I will limit myself to the trio, Indrani Perera, Annesley Malewana and Clarence Wijewardena. Indrani of the Three Sisters and Clarence and Annesley of Golden Chimes, and their bittersweet re-union in Super Golden Chimes were at the helm for the entire period. Their stamp in the pop scene has survived all these years and naturally they have been dubbed the Queens and Kings of the fifty plus year’s history of the Sinhala popular music.

The stars of Indrani, Annesley and Clarence have burned brighter for more than half a century and I will be excused for selecting the three for the purposes of this article. Indrani’s crystalline voice delivering folk like verses were framed in exquisite musical arrangements prepared by Clarence Wijewardena, the songwriter and producer extraordinaire. He was bass guitarist devising dynamic guitar breaks as a value add, especially to the moody emotion filled songs such as Dilhani and Kalpani Duwani. He once said in public that as a teen he was an avid listener to Beatles and Shadows with Cliff Richard and that after secondary school all he wanted was to make actual music with his interiorized musicality. Indrani’s vocals were often multilayered with harmonies by her sisters. Annesley’s dusky voice ranging in delivery from home based country anthems to solemn folk balladry attracted large crowds and sold the records under numerous labels.

Trained in gospel singing, in Indrani and others the Sri Lankan audiences discovered a national treasure That won lasting affection for bringing us nostalgic experiences of our own lives; beauty of the landscape, undiluted romantic innocence, and the warmth of a human community. Throughout their long and brilliant careers spanning five decades they entertained millions of Lankans. Working long hours in a undervalued vocation in the 60’s and 70’s we who are the recipients of their precious gift owe them an enormous debt of gratitude. A career in music is hard work, a lot of sacrifice, but more importantly need a lot of perseverance and patience.

The integrative revolution

The singer and audience relationship is about connection; above all an emotional bond that make you cry, laugh, think, hold out a hand, in brief empathic union. The bands playing western music were moving the people on the dance floor while the Sinhala groups were moving people in an atmospheric emotional direction. Beyond the form they also were driving hard a message to bring the nation together. In sonata style, without big guitar moments, warbling in unhurried tunes, fittingly mellow with mundane lyrics made an impressive appeal.

It was the immense capacity to put together a poetic collection of images, sounds, scents and stories, wrapped in mellifluous but simple words. They produced a grand alchemy of songs all testimony to the indigenous artists’ engagement with the country and its people, the common folk. At the same time they evoked something within all and we felt connected. It was a part of the little tradition of the Sri Lankan culture that brought us together.

This change in the music topography and culture that took place from the decade of the 60’s points to something beyond the confines of musical creation and musical thought to the wider sphere of social life and social strife. This was an integrative revolution responding to kindred developments in the realm of wider society. The integrative revolution was led by the suburban Christian youth.

Clarence Wijewardena, mindful of the furious forces that were beating against the barriers that hemmed them in, stuck to his motto throughout: semplice-sempre, simple in style and presentation. Contemporary reality mirrored and expressed in spirited conversations with few instruments, he was able to compose songs like Sigiriya, Ruwanpuraya , Kalu ganga Udarata Kandukaraye, Dunhinda Manamali, Wana bambaro ohoma hitu, Dilhani, Ela dola piruna Gon Bassa, Mango nanda, Gamen liyumak avilla, Udarata niliya heda wage, Kalu mame, and many others disregarding formalistic aspects of language and idiom. Of course some of the words were criticized and even censored for being rustic.

Use of words such as Himihita wetiyan, Umbata rideyinam, ohoma hitu, and bithu sithuwam neluwo were subjected to trenchant criticism. But the most important fact was that this music, lyrics and tempo appealed to all segments of society, Buddhists, Christians, Hindu and Muslims could enjoy breaking ethnic and class barriers. In sociological parlance it can be said that while the earlier bands and music were westernized, the Sinhala pop music was sanskritized.

The authoritative Indian sociologist M.N.Srinivas captured the social changes in the 1960’s in India by devising the term sanskritization for a similar process that we can freely use to describe the changes in Sri Lanka ushered in by popular music. Even to the urban society it impressed both on an intellectual and emotional level. I may be pursuing a tenuous connection leading to a dead end but I considered it necessary to record this transformation as a valuable contribution, as reminded by Reverend Malcolm Ranjith quite candidly. It was a social movement and the implied consequences may not be intended. However as Hegel once noted philosophy should avoid political entanglements.

Music and song became the catalyst that unleashed the forces and opened vistas of all communities including the upper middle classes to fall in line. No doubt there was opposition but there were also entrepreneurs like Gerald Wickremasooriya who unstintingly offered assistance. Perhaps they understood the underlying integrative element because it was a contrapuntal message, given better than any political pamphleteer. Popular artists liberated the melody from its tight constrictive wordy bodice and made it part of the common man’s idiom. More importantly, the text invited all social classes and communities to embrace the ethos of our common Sri Lankan heritage. Maw bima obei sithala, rata deya kere bandila, panamen obei sithala, pili gatha yuthui puthune, they pleaded.

One needs only a comparative perspective to understand how the thought content of their music presented a contrasting but an inclusive society in which all communities and religions to wipe out that ordre positif of the old feudal regime and enter a much better ‘ordre naturel’ preordained by the all-wise and all loving deities whose work men can mar but never mend. Was that the confidence they possessed to accomplish their task fighting all barriers that playwrights like Professor Sarachchandra could not easily dismantle.

Professor K.N.O Dharmadasa noted in an introduction to a booklet on Maname the interesting and enlightening dialogue between Professor Sarachchandra and a Cinnamon Gardens lady on the steps of the Lionel Wendt theatre on one of the early days of Maname where the lady said that Sinhala nadagama appealed nicely to the likes of her kitchen maid. No more profound expression of the class divide of the Sri Lankan Weltanschauung is needed. The upper classes were steeped in a world quite alien to the common Sri Lankan heritage. We therefore pose the question whether the musicians, mostly brought up in the Christian Church background lifted the impenetrable barricades as they sang ‘Api enawa murakawal okkoma bindala’ with much more ease, one wonders.

In the 1950s and sixties the freedom, equality and liberty that independence had granted to Sri Lanka was blotted out by dark shadows of communalism and religious bigotry, a society already fractured by caste and creed. The Bandaranaike revolution was hardly inclusive. The politics at the time failed to create a liberated society, a society that is able to express a richer and fuller life. The people’s revolution brought out the monstrosity of communalism more repulsive than the semi feudal class oppression that it was intent on driving out.

Here we draw the power of the form and thought of creative art in song and music. These musicians, who were the progeny of parents outside the ‘purists’ managed to enter the depths of the consciousness of those who were distracted by the people’s revolution and unobtrusively connected them with the Sinhala mainstream society. While appealing to the common multitude they also entered the homes of the rich and famous freely and all this without political undertones.

All we can say is ‘Thank you for the music and thank you for bringing us close’.