Gated and locked public playgrounds in Colombo By Arundathie Abeysinghe

Currently, public playgrounds in Colombo 2 and 3 are disappearing and those that remain are gated and locked, accessible only to those who can pay for entry. These playgrounds were used by those housed in cramped quarters within densely populated neighbourhoods without private gardens or shared courtyards. They became essential spaces for the community’s play and recreation. Young people gathered for cricket and football, and neighbours chatted in the open spaces that offered a welcome respite from homes hemmed in by the city’s concrete intensity.

In Slave Island, the erosion of public space is severe with playgrounds and community spaces surrendered to private real-estate developers through a series of opaque administrative manoeuvres and unchecked encroachment by corporate conglomerates.

For generations, these public playgrounds played the role of the social heart of Slave Island ‘s (Kompannaveediya in Sinhala) working-class communities.

Accelerated by urban development drives, including the State’s post-war Urban Regeneration Programme (URP), since the mid-1990s, Colombo’s public spaces have been shrinking and working-class communities are cramped into high-rise flats in the city’s outer peripheries. Currently, residents find themselves without access to spaces their parents and grandparents freely enjoyed.

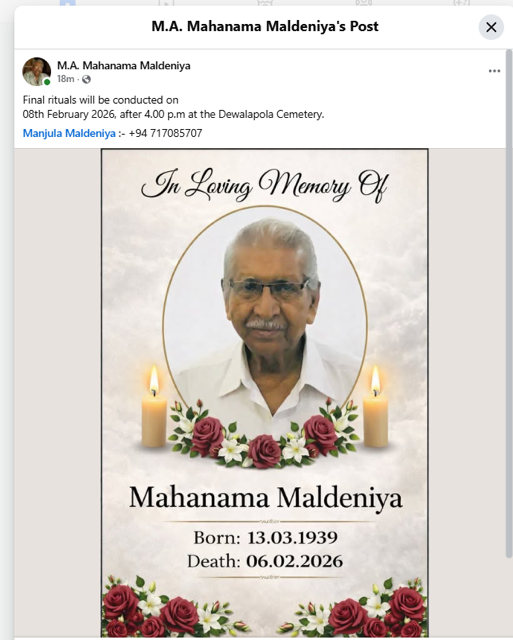

According to Slave Island residents “Stanley Jansz Playground, popular as Mati (Clay) Park, served as a hub of community life in Kompannaveediya. According to archival records, the ground has been established around 1924, with over a century of public use. Yet, according to community records and social media, the space has been privatised around 2018. Currently, access is restricted and contingent on payment, indicating a clear shift from public ownership to commercial control.”

“Apart from official playgrounds, during our childhood, there were smaller open spaces that once served as informal play areas. Many such locations are currently fenced off, claimed by a private corporation for warehousing or used as parking spaces for vehicles,” residents emphasized.

According to senior academics, “unchecked political power can quietly seize public land. Muttiah Grounds is one such example. The ground was leased to Colombo Municipal Council CMC) in 1933 as a community playground.”

“Certain issues cannot be openly challenged. Legally, Muttiah Grounds still belongs to Colombo City, yet, in practice, it has been converted into a private construction site. In addition to political coercion, administrative gaps too have left Colombo Municipal lands vulnerable as there is no complete, updated inventory of city-owned lands. Many residents are of the view that Municipal land is “a blind man’s treasure”, valuable, untracked, yet can be easily seized.”

Meanwhile, City League Playground in Slave Island, a prominent venue for local football which was originally meant to serve the community is currently under private control. According to archival records, including Colonial Secretariat reports, the land was officially vested in the CMC in 1916 as a public football ground. Although, the site was first leased to private entities in 1940s, reflecting a long-running pattern of informal privatization, the public had free access to the ground until 2009. Currently, City League manages the grounds, requiring a fee for public access.

In major cities in the world, parks and playgrounds act as the ‘communal living room’ and the ‘city’s lungs.’ The issues of Colombo’s playgrounds are quietly slipping into private hands enabled by opaque administrative processes as the CMC has failed to maintain a clear, updated inventory of its own lands.