Lamprais – An Inheritance from the Dutch

Source:Amazon

This narrative complements my previous e-mail on the Dutch influence on the Burgher community and deals predominantly with the renowned “lamprais”, which have been subjected to appalling and repulsive abuse in its contemporary preparations in Sri Lanka.

A brief explanatory note needs to precede the remarks that follow, to place them in context.

As you are aware, in 1998, the Dutch Burgher Union commemorated its 90th Anniversary, with the main event of the celebration taking the form of a grand public Dinner-Dance, which was, for the first time, held at a venue [a 5-Star Hotel] other than the DBU’s own hall at Thunmulla. One of the features for that evening was the production of a Souvenir booklet to be handed to everyone who attended. As Chairman of the Organizing Committee, I was determined that it should take the form of a valued keep-sake, to be cherished, rather than thrown away following the event, and that, I am happy to state, was achieved, as many who attended the event have preserved their copies, notwithstanding the lapse of 22 years.

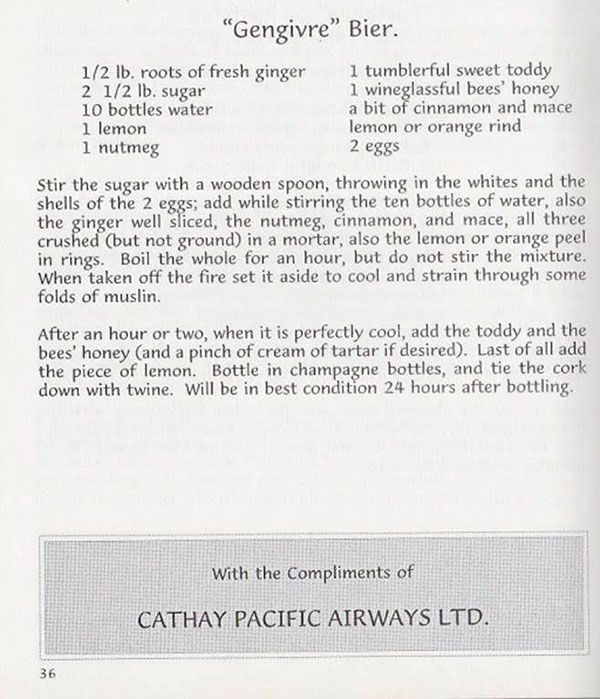

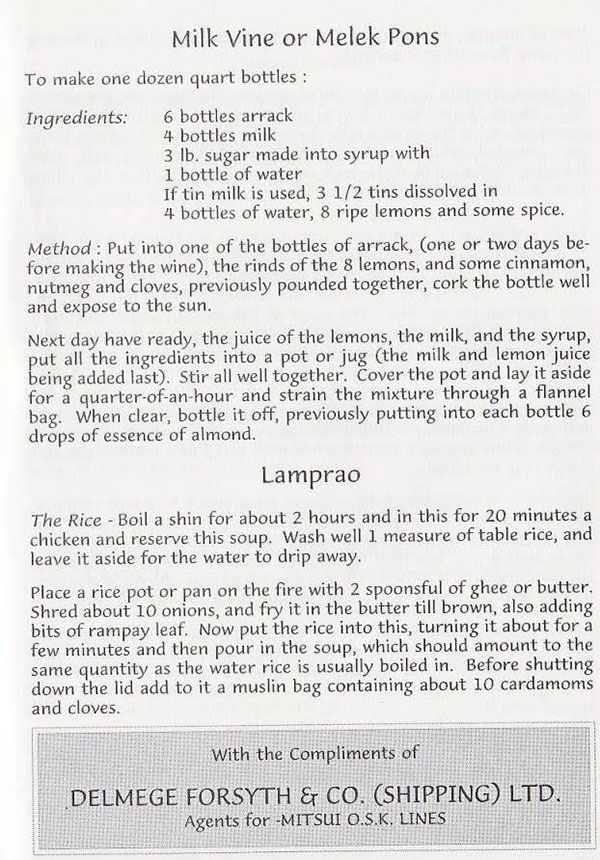

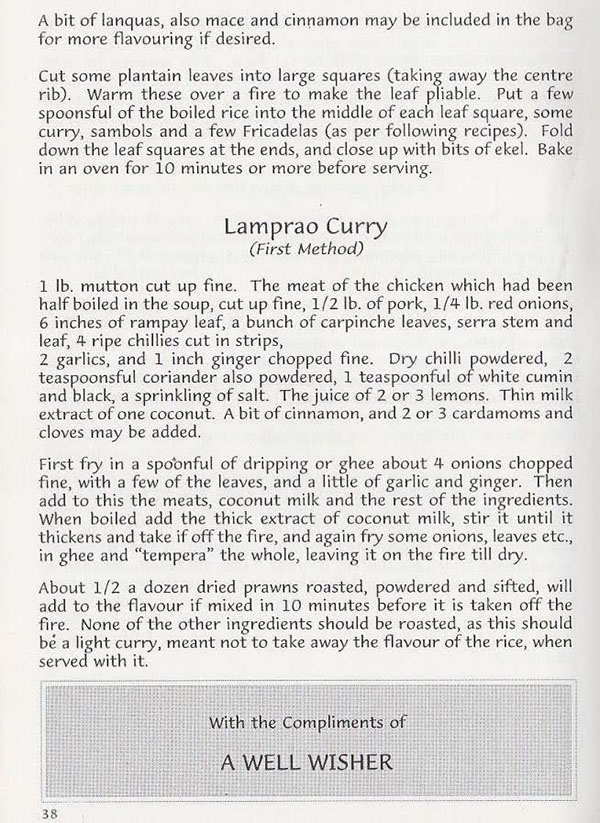

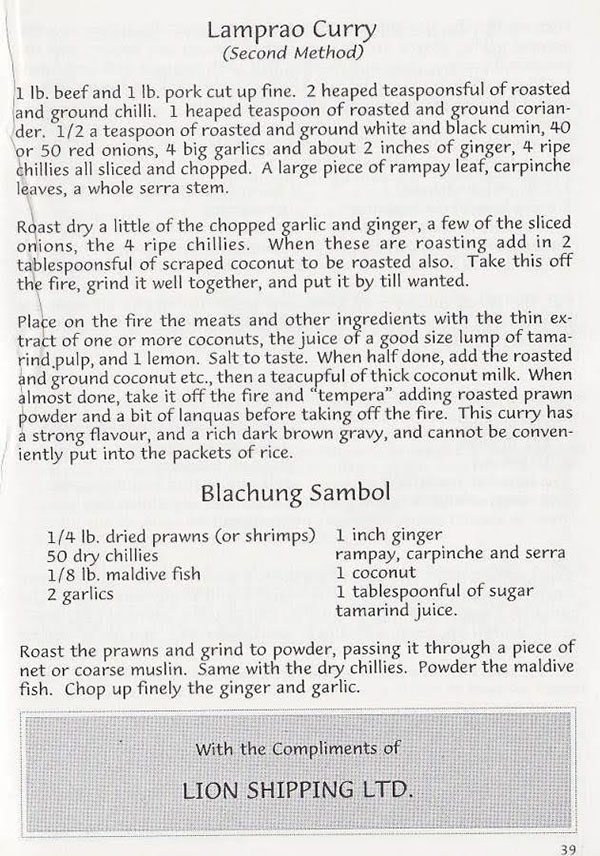

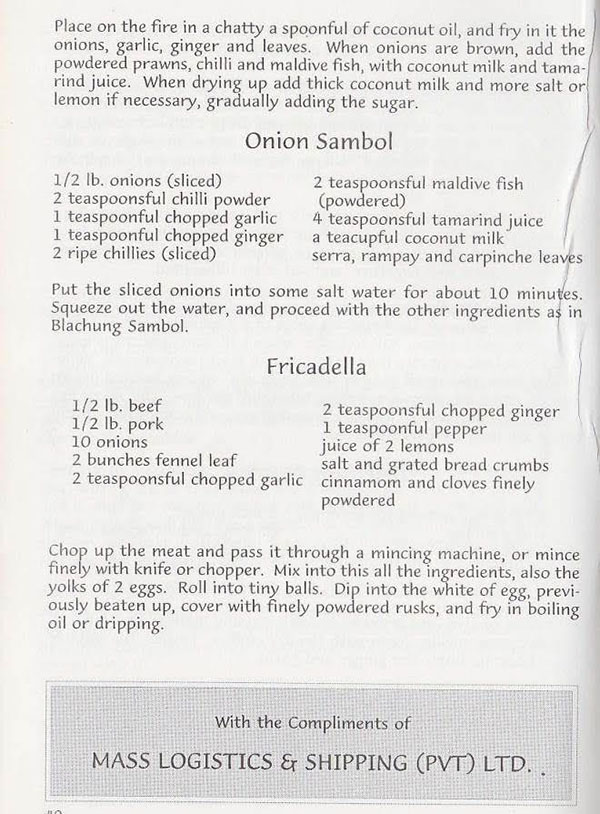

In the process of collecting material for this publication, Reggie Poulier, through his wife, Yvonne, a member of the Organizing Committee, kindly granted access to his father’s extensive library, from which we came across a book titled “Rare Recipes of a Huis-vrouw of 1770”, a treasure-trove of Dutch and Portuguese recipes of that era. We selected a few of the better known items featured in this book and had them reproduced in the Souvenir. There were [and I use the spellings as they appeared in the book], amongst others, Broeder, Bolo de Amor (Love Cake), Poffertje, Ijzer Koekjes, Fougetti, Bolo Fiado, Boroa, Pentifreetu, Pastelles or Pastelao (Patties), Gengivre Bier, Melek Pons (Milk Wine) and Lamprao (and accompaniments, such as the curries, Blachung, Onion Sambol and Fricadella). Over the years, many of these recipes have undergone modifications and probably taste better than the originals, although the authenticity of the major components – not necessarily all the ingredients and the methods of preparation – remained intact.

It is interesting that, as they took back home with them their passion for the Rijsttafel** and Nasi Goreng, the Dutch brought their love for Lamprao with them to Ceylon from Indonesia, which country was also a colony of the Netherlands till about seven decades ago. In fact, the Dutch ruled Indonesia from around 1600 till 1949, while their presence in Ceylon was from about 1650 to 1796.

Since polythene was not invented at that time – in the 1600s and 1700s – and paper was not suitable for wrapping accompaniments of rice, such as curries and sambols, which tended to seep through, on account of its high porosity, the banana leaf was found to be ideal, in that it was hygienic, when washed and warmed lightly over a flame, its malleability and waxy nature made it impermeable, thereby, preventing seepage and preserving the food wrapped in it for longer periods. It was also found, on a account of the presence of chlorophyll in it, to impart a desirable flavour and fragrance to the rice wrapped in it, which is very distinctive in lamprais, and, in fact, makes them taste better after about 24 hours of being wrapped and warmed prior to consumption. The presence of polyphenols in these leaves have antioxidants that are said to help curb diseases like Parkinsons, and, as in the case of Green Tea, is believed to promote health and fight a range of other diseases.

I recall my mother mentioning that the lamprai curry should comprise five meats, i.e. chicken, pork, beef, mutton or lamb and liver. However, the “Old Dutch Recipe” offers two options. The first – mutton, pork and chicken; the second – just beef and pork. My sister also remembers the five meats recipe my mother used, but says that my mother’s written recipe provides for just three meats. Perhaps, she improvised, as these special little touches were passed on from mother to daughter and were generally not recorded in writing, just as my sister makes her lamprais with five meats. Also, the “Old Dutch Recipe” mentions, apart from the curry, only the “Blachung” sambol, the onion [seeni] sambol and the fricadellas, which are, in fact, what we refer to as ball cutlets made of compressed beef, or a combination of beef and pork – never fish! This is because these items did not spoil easily, as there was no refrigeration then. Now, one may use one’s discretion in including brinjal pahi and a dry ash plantain preparation. Usually, each lamprai has just a large cup of rice, with the accompaniments, which really is just right, as it does not make you feel too full. However, Sri Lankans tend to need more than that to fill their tummies and the tendency is to include more rice these days.

I am told that in Australia there is a tendency to place a slice of ham underneath the rice in each lamprai, and a dab of butter on top, prior to warming it. I have not known of that practice being followed in Sri Lanka and am intrigued by it.

I am forwarding a scanned extract from the souvenir of the lamprais recipe, which covers pages 37 to 40. The inclusion of pages 36 and 41 was unavoidable in the scanning process and are not relevant to that recipe. Please note that this is the recipe of the “Huis-vrouw of 1770” and not my mother’s!

**Rijsttafel: On my many visit to The Netherlands, I never failed to enjoy a Rijsttafel with friends. Its literal translation is simply, “rice table”. As in the case of “Nasi Goreng”, it was an adaptation by the Dutch of an elaborate Indonesian meal.

The duration of the meal usually extends over about 2 or even more, as it comprises anything between twenty to sixty side dishes, served in small portions, accompanied by rice, and has to be eaten at leisure to savour the diversity of flavours. The side dishes include beef, pork, mutton, chicken, sea food and vegetables prepared in different forms, flavours and textures, served with chutneys, pickles, sambols, and satays.