Malini Fonseka: Completing the circle- by Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

Though their performances seem maudlin to us now, the earliest screen actresses earned their living through tears and sobs. When the one-reeler began giving way to the two-reeler, directors began borrowing from Victorian literature. This was a literature of chaste women and rapacious womanisers, in which the heroine usually ended up falling into the wrong hands, having rejected her first lover, and the latter endeavoured to save, if not redeem, her.

Not surprisingly, the first directors banked their careers on their actresses, turning them into mascots: thus Florence Lawrence became “The Biograph Girl”, while Mary Pickford became “Little Mary.” The films they starred in offered very little variety: they were all variations on the same stories and themes. But audiences loved them, and audiences kept returning.

Something of the ineffable charm of these films survives in the performances of these actresses, most of whose names we have forgotten today. The women the latter played defined themselves by their fragility: always up for grabs, they fell victim to tricksters posing as their paramours, and had to be saved by the humble, usually poor lover they had rejected earlier.

Even after the two-reeler gave way to the six-reeler, the new actresses retained this sense of tragic fragility and sensuality in their characters. When film production travelled the world, actresses everywhere inadvertently emulated these stars. In Sri Lanka, the first of these tragic heroines, at times proud, always sensitive, came to be played by Rukmani Devi.

From Rukmani Devi to Malini Fonseka, we traverse 20 years: between Kadawunu Poronduwa, released in 1947, to Punchi Baba, released in 1968. The sensibilities that defined these two could not have been more different. Rukmani’s conception of the heroine, rooted fundamentally in the Victorian melodrama, the Hollywood of D. W. Griffith, and the drama of Parsi troupes, occupied a universe where the heroine lived solely for her lover. She usually held back, because the moral compass that governed her life prevented her from asserting her autonomy.

This is not to say she accepted defeat: in a Rukmani Devi film the heroine always wins, yet she lets events determine her fate. There’s no attempt on her part to shape her destiny; it’s the men who end up defining its course for her. Like the lovers of Enoch Arden, a work whose theme we come across in so many Sinhala films, even in Kadawunu Poronduwa, her romance is marred by reversals of fortune and misfortune: she loses sight of her lover, marries another, more often than not against her will, and is reunited with the man of her dreams in the end.

A world or two away from Rukmani’s maudlin heroines, Malini Fonseka became the idealised female, the fetishised woman, in a different way. She became the symbol of a new woman in an era marked by a new consciousness: the consciousness of a Sinhala Buddhist petty bourgeoisie, whose rise accompanied the transition from 1948 to 1956 and beyond.

A world or two away from Rukmani’s maudlin heroines, Malini Fonseka became the idealised female, the fetishised woman, in a different way. She became the symbol of a new woman in an era marked by a new consciousness: the consciousness of a Sinhala Buddhist petty bourgeoisie, whose rise accompanied the transition from 1948 to 1956 and beyond.

What explained Malini’s extraordinary popularity? Even in her worst films, she gave a decent performance, and in all her performances, she made every man who came across her want her. Directors who realised this tapped into their box-office potential, not by pairing her with the big stars of the time, but by separating her from the characters they played.

Malini’s characters not only made us want her, they also made us go to any lengths to have her. She didn’t want anyone dominating her, but she got every man to wish they could dominate her. It’s difficult to think of any other actress here who could equal her on that count. Probably that’s why she was never cast as a femme fatale; the closest to such a figure she got was the heroine in Sasara Chethana – a movie she herself directed. That role fitted her mould as much as the cast of the tragic, spurned, defenceless woman did, which is to say it didn’t fit her at all.

In K. A. W. Perera’s Wasana, Vijaya Kumaratunga croons Jothipala: “Oba Langa Inna” distils the lonesomeness that so defines Malini’s lovers. Separation makes the heart grow fonder; this was the underlying philosophy in Wasana and, later, in Apeksha, where, if you look beneath and beyond the class conflicts within which the plot unfolds, the entire story boils down to Amarasiri Kalansuriya’s desperate attempts at winning Malini.

Some of her most memorable commercial outings in the 70s – the films of K. A. W. Perera, for instance – present her like a doll: fragile, defiant, yet rebellious. In Sahanaya, for example, she’s paired with Gamini, but their roles are somewhat inverted: she’s the spoilt heiress, he the idealist who paints her without her knowledge and who she slaps when she finds out. Sequences like this – multiplied many times over – show how she could ensnare the men of her movies.

If you sense a naive sense of self-discovery in her first roles it’s because that more or less echoes actual persona. Malini Senehelatha Fonseka was born to a modest working class family in 1947 in Peliyagoda; she was the third child of a family of 11.

Initially educated in Nugegoda, she later shifted to Gurukula Maha Vidyalaya, Kelaniya, where she befriended some future collaborators: Wimal Kumar da Costa, H. D. Premaratne, and Donald Karunaratne.

Gurukula bordered on the Vidyalankara Campus, now the University of Kelaniya. One day some students from Vidyalankara came over looking for an actress to play a lead role; the University had no women. The dancing teacher at Gurukula considered Malini; having asked her, he chose her once she obtained permission from her parents. The play, Noratha Ratha, directed by H. D. Werasiri, marked the first time she had acted outside school.

In 1965 she took part in Akal Wessa, a play written by Sumana Aloka Bandara that won for her a

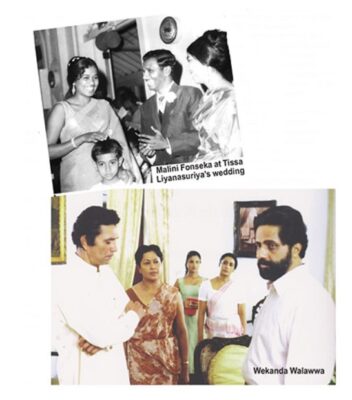

Best Actress Award and the attention of two members in the audience looking for a newcomer to play the leading role in an upcoming film. Tissa Liyanasuriya and Joe Abeywickrama made their choice that evening; remembering his decision many decades later, Tissa told me, “Some people thought she was too thin for my film, too untried. Joe on the other hand was satisfied with her, as was I. So we took her in. It was a choice we never came to regret.”

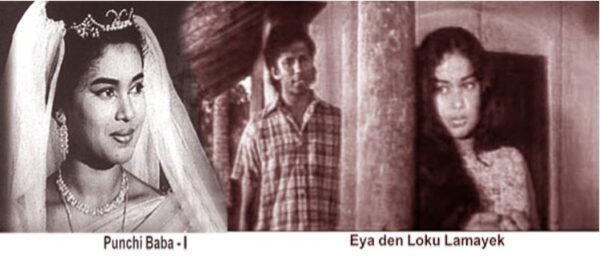

Punchi Baba marked Malini’s entry into the cinema. Of her encounters onboard it, Liyanasuriya told me, “I didn’t order her about. She seemed fully involved.” That sense of being involved was what defined her career in the 70s, but in these first few performances (including her second, as the sister to a romantically obsessed lover, played by Henry Jayasena, in Dahasak Sithuvili), she was more the girl who lived next door than the girl who could win your heart.

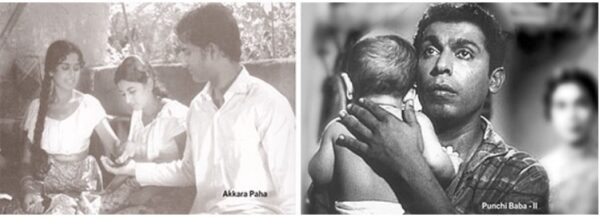

You see Malini shedding this naive avatar from herself with these first roles, particularly with Akkara Paha, where she’s the sister to another obsessed brother. In Dahasak Sithuvili she more or less succumbs to Henry Jayasena’s moods; here she’s more contained, more assertive. The girl from Punchi Baba was growing, discovering herself, letting herself be known.

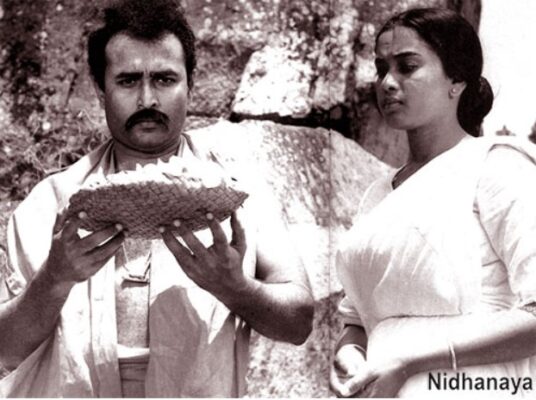

By the time of her performance in Nidhanaya, the culmination of all those outings that paired her with Gamini Fonseka, she has become aware of her potential: she has let go of being the girl next door. This was true of Siripala saha Ranmenika, and the films of Dharmasena Pathiraja: from a minor role in Ahas Gawwa to a titular role in Eya Dan Loku Lamayek, to more assertive roles in Bambaru Avith and Pathiraja’s understated masterpiece, Soldadu Unnahe.

It’s a sign of her prejudices perhaps, but when I ask her what her favourite film is, she replied, “Aradhana.” This film, directed by Vijaya Dharma Sri, has Ravindra Randeniya befriend her, and then, pushed by guilt and infatuation, come back to claim her. His character in Dharma Sri’s film is reminiscent of the villain in Vasantha Obeyesekere’s Dadayama. The entire story, at one level, inverts Obeyesekere’s plot: it’s Dadayama with a happy ending, the sort Malini could find a place in, the same way Swarna Mallawarachchi could in Obeyesekere’s film.

That it was screened in the 80s, in colour, is not a coincidence; Malini admitted to me during our interview that these represented her favourite years, years in which she rose from a performer to an occasional director: Sasara Chethana in 1984, Ahinsa in 1987, Sthree in 1991, Sandamala in 1994. These attempts all revolve around femininity and motherhood; Sthree, for instance, draws a parallel between her character’s travails and those of an elderly cow.

That it was screened in the 80s, in colour, is not a coincidence; Malini admitted to me during our interview that these represented her favourite years, years in which she rose from a performer to an occasional director: Sasara Chethana in 1984, Ahinsa in 1987, Sthree in 1991, Sandamala in 1994. These attempts all revolve around femininity and motherhood; Sthree, for instance, draws a parallel between her character’s travails and those of an elderly cow.

As the years went by, she took on increasingly matriarchal roles, as shown by her performances in Punchi Suranganawi (2002), Wekanda Walauwwa (2003), and Ammawarune (2006). It would be impossible to omit her role in Prasanna Vithanage’s Akasa Kusum (2009), given how much it symbolises the end of a journey, a rite of passage, for her career.

For Akasa Kusum, her best performance since Bambaru Avith, Malini Fonseka won a number of awards here and abroad, including the Silver Peacock at the Indian Film Festival (the “biggest achievement in my forty years”, as she put it). The film has her play the role of a former film star whose return to fame is marked by scandal: basically, a Norma Desmond in Colombo.

One can discern a kind of naked, sublime austerity in Malini’s performance here. You sense little to no exaggeration; more so than in her other performances, she deliberately underplays her part, denuding it of any romantic excretions. This underplaying is essential to the character of Sandya Rani, whose nostalgic reveries into the past are underscored by a harsh, all-too real present. The clash of personal feeling and social reality (especially after her involvement in the scandal) is at the epicentre of the narrative, and Malini epitomises that clash in a way that surpasses nearly all her performances, perhaps barring Bambaru Avith and Eya Dan Loku Lamayek.

Vithanage’s film thus represents the end, not of an era, but of a career. It marks the achievement of a goal Malini’s career has been building up to: the shedding of the excessively theatrical from her acting. For far too long, she’s been the girl next door; by now she has become fully conscious of the rift between fantasy and reality, and has come to accept it. Her performances have been, in that sense, all attempts at self-discovery. And in Vithanage’s film, she completes the circle.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com