NILGALA FRONTIER – by Ranil Bibile

NILGALA, where Raja Singha, Lord of the Tûn Sinhalé, vanquished the man-eating crocodile, was a dead end.

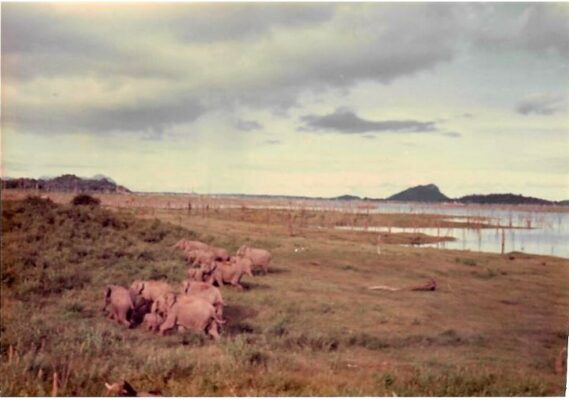

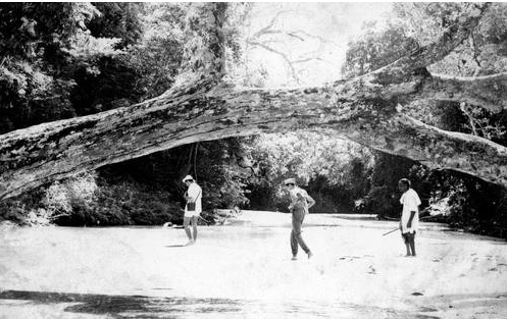

ONCE, many years ago, whilst exploring this roadless terrain on foot, I came across the remnants of an ancient hewn-stone fortress. It was situated on a rocky rising rib of land between the roaring river and the brooding peaks of Ulhela and Berayahela, and lay half buried amidst the tumbling boulders and man-high mana grass of this place. I had just begun to investigate the crumbling battlements when a herd of elephants approached me, forcing me to retreat towards the waterspread of the Senanayake Samudraya.

Though I longed for years afterwards to return to this remote ruin, to touch the stones once again and feel them come alive with the history they must have known; it was not to be. As the years went by, I passed oft times within a league or two of it on my many restless wanderings the Maha Vedirata. Yet I never set my eyes on it again, and often wondered as to who had built it and for what purpose it had stood there in those deep and forlorn forests, beyond the back of beyond, with nary a village or human settlement for miles around. Had it guarded a city that still lay undiscovered and unrecorded in our chronicles, perhaps lost in the mists of time? If not a city, then perhaps a great highway? But if so, then a highway from whence to whence? For today, only an elephant trail brushes past those ancient stones, and vanishes into the tall grass that rustles gently in the winds that blow across the waters of the Samudraya and up the Canyons of Makaré.

THE year was 1602 A.D. The Portuguese held sway over the maritime provinces of the island, especially in the west. In the rugged mountains, the Kingdom of Kandy held out against the invader and lived its life of independence a hundred years after the first Portuguese men of war had landed. The King of Kandy – Vimala Dharma Suriya – the former Konappu Bandara, wished however for an ally to oust the Portuguese, and in the process struck upon the Dutch. And thus came to the shores of Ceylon, the Dutch admiral Joris Van Spilbergen, the first ambassador from the Prince of the House of Orange, to the only potentate in the east who claimed to wear a crown. A journal of this embassy kept by an officer of the expedition stated that the journey from the roads of Batticaloa where the Dutch ships dropped anchor, to the kingdom in the hills, was made through Nilgala, Wegama and Alut Nuwara. Reading that account, I felt that it may be a clue as to why there was a fortress in Nilgala. For, if Nilgala had once been an important way station on a route from the east coast to the Kandyan Kingdom, then a fortress may have been essential.

In 1620 A. D. the Danish admiral Ove Giedde too dropped anchor off the east coast of Ceylon and according to his journal he journeyed to Mahiyangana to see the King, passing through Nilgala and Bibile.

An Ola Leaf Sannasa, extant, has it that during the reign of King Rajasingha I, a Veddah chieftain by the name of Maha Kaira Wanniya fought on the King’s side against the Portuguese, and as a reward, his offspring were granted, on the Sannasa, the village of Bibilegama in the Wellassa division in 1611 AD by King Senerat. They settled down at Bibile, four leagues from hoary Nilgala, and for generations thereafter ruled the area. In all that time Nilgala remained an important junction, right up to the Nineteen Hundred

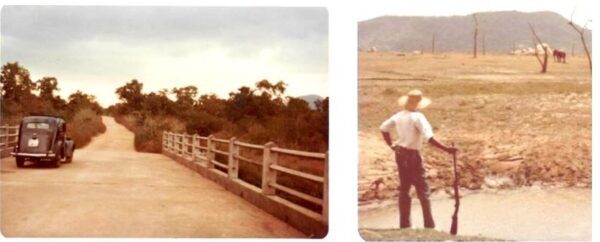

and Thirties when the late C. W. Bibile, the last Rate Mahattaya of Bibile-Wellassa – a descendent of Maha Kaira Wanniya – used to bivouac at the old Nilgala and Ambilinna Circuit Bungalows with his bullock cart caravan whilst on circuit of the Maha Wedirata.

But the history of Nilgala and The Valley goes back by the millennia.

Dr. R. L. Brohier stated that; “Dim traditions supported by other evidence associate the Gal Oya Valley with man of the Old Stone Age ….this naturally refers to wild untamed Ceylon, long before its history began to be told in lithic record and monument.”

Elsewhere he stated; “Apparently in times long past there were along the banks of the Gal Oya several natural hollows or villus..…was consequently of much importance in Pre-Christian times”. Parker talked of “several reservoirs in existence there in the first three centuries Before Christ.”

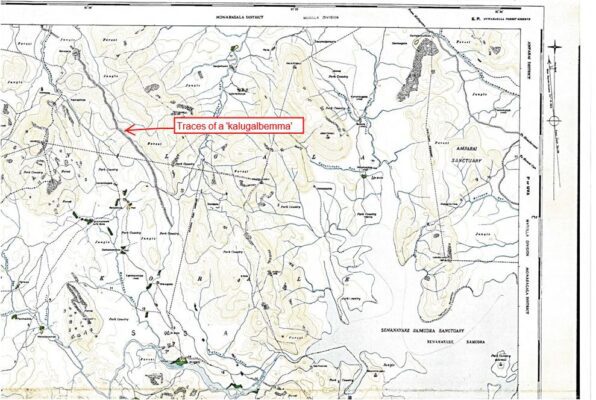

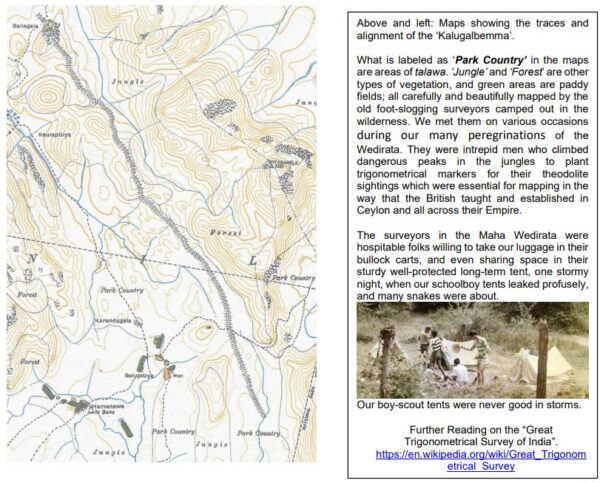

As for myself, I have seen in this region, the traces of a ‘Kalugalbemma’ which the timeless oral traditions of the villagers’ claim is the remnant of a great highway which ran from the Raja Rata in the north to the Kingdom of the Ruhuna in the south during the dim distant past. North to south and east to west, Nilgala was a crossroads: Once upon a time so long ago.

THE centuries had rolled on. From the ‘Pre-Christian’ eras, through the times of the Veddah peoples, to the coming of the Sinhala race, and the heyday of the Kandyan Kingdom, and through the invasions and embassies of the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British, as men and armies had come and gone, Nilgala had been there and seen it all, and remained, as always, a very beautiful spot upon this earth.

It was the British who explored the region most after the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom and left many a written paean to its lure.

Sir Emerson Tennent, Colonial Secretary 1845-1850, talked of “open glades and forest scenery…..park like meadows and surrounding woods… trees of majestic dimension and pastures through which the deer troops in herds. ”

Sir Samuel Baker in 1848 said, “I cannot describe the country better than by comparing it to a rich English park, watered by numerous streams and large rivers, but ornamented by many beautiful rocky mountains, which are seldom to be met with in England. If this part of the country had the advantage of the Newera Eliya climate, it would be a paradise. ”

Governor Sir Henry Ward who travelled down the Gal Oya through Bibile and Nilgala in 1857 had this to say: “All that nature can do to make a country attractive by the most beautiful combination of Mountains, Forests, Rivers, Fertile Valleys and rich grazing grounds upon the Hills is to be found here scattered with a profuse hand”.

Thus did many an explorer pen a paean to Nilgala.

BUT everything is impermanent and must change even after millennia. By the Nineteen Hundred and Forties Nilgala was only a small hamlet by the river. In that time disease and dissension wrought havoc upon this place, and its people abandoned it and scattered to other outlying settlements which had melodic names: to Hamanawa and Pammedilla, to Maladanambe and Damunuwinna, and further afield. The historic whitewashed mud and wattle circuit bungalow was all that remained, decaying peacefully in the shade of a huge mara tree amidst a grove of jak and plantain trees overlooking green fields of paddy now worked by the goviyas of Bulupitiya. Across the paddy lies a line of stately Kumbuks along the banks of the Gal Oya, from whence emanates the soothing music of waters rushing over the huge granite slabs of the river, for which reason this spot is called Lokgal Oya by the locals.

THEN, as the 20th Century reached its midpoint, mechanical monsters the likes of which this isle had never seen, descended upon a spot of land below a rock called lnginiyagala to the east of Nilgala.

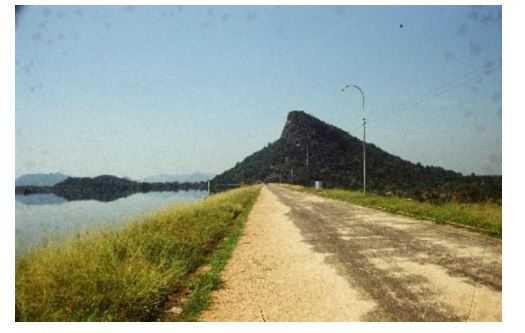

And they changed the face of the earth. The dramatic rock of Inginiyagala was married to another hillock a mile away, and thus were the waters of the Gal Oya, which had flowed untrammeled through this valley since the earth was first formed, trapped and hindered on its journey to the sea.

As the pent-up waters rose relentlessly over the many monsoon seasons, they submerged tens of thousands of acres of beautiful earth; and the historic lands around Nilgala, of Wellassa, and of the Maha Wedirata, drowned.

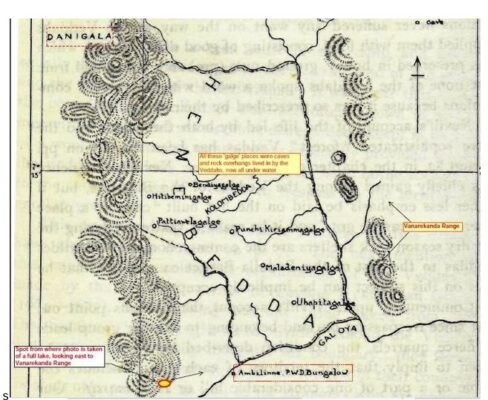

The lands which had been the home of the Veddahs for many millennia, the cave homes to which they had given strange sounding names such as Bendiyagalge and Hitibeminigalge, Uhapitagalge and Punchikiriammagalge, drowned.

The lands over which the great highways had rolled in the kingdom times of the past, drowned. They had been highways from the Country of the Kings – the Rajarata – to the country of the Ruhuna, and highways from the ocean roads of Madakalapuwa to the mountain kingdom of the Kandé Udarata.

They drowned. The glade-like lands of Aralu, Bulu and Nelli, that had been the medicinal gardens of the old peoples, drowned.

The historic circuit bungalow at Ambilinna drowned. When the new Sea of Senanayaka grew to its full extent, its meandering waterspread covered the the Maha Wedirata to the east, and Nilgala became a cul de sac – a dead end.

The Nilgala circuit bungalow crumbled. It’s water-well came to be occupied by dead animals.

And Nilgala died.

The fortress had even then been living a century or more entwined in jungle vines.

BUT out of this death, a new life arose. Beyond the Canyons of Makaré, and deep in the heart of the Nilgala Frontier, river, lake, and mountain met with great beauty and harmony.

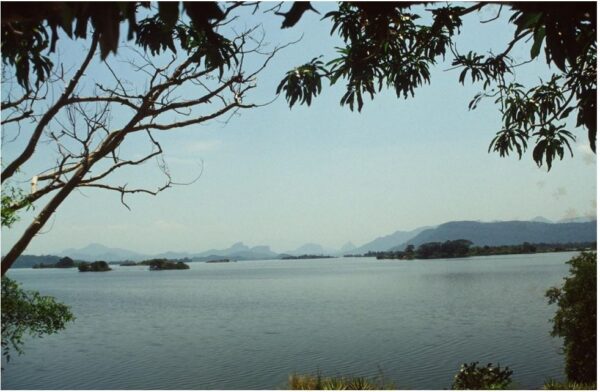

The waters that drowned the great vale became home to teeming aquatic life and were fished by birds that swooped down from the sky and by men who sailed their outrigger canoes through the quiet meandering bays and the windswept open stretches of the biggest lake in Lanka.

The waters that were pent up behind the Inginiyagala Dam were allowed to leave the lake only by generating power for the people. In the lowlands to the east, these self-same waters made thousands upon thousands of paddy acres green, set little subsidiary lakes aglitter with replenishing waters, and made old and dying villages resurgent once more.

Even the great groves of trees that drowned and died in the new Sea of Senanayaka, became breeding grounds for countless flights of aquatic birds. The sylvan glades and deep forests of the upper reaches of the lake became havens for elephants, buffalo, deer, sambhur, bear, and all the other creatures which inhabit our forests; blessed at last with a perennial supply of food and water.

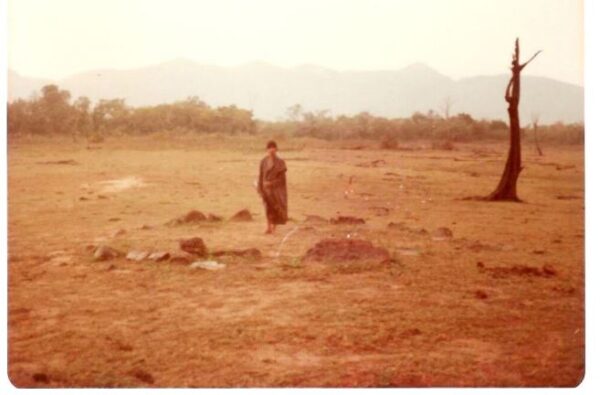

But when the rains are late in the season and the lake low in water, there emerges the ghosts of the lakebed – the desolate cave-homes of the Veddahs and their gaunt granite outcrops, the highways of history, and the signs of man from the Old Stone Age. In its upper reaches, the lakebed briefly turns into a brilliant carpet of green grasses and wildflowers, and the grazers and browsers come out to feed in the morning sunlight, walking nonchalantly over ground that man had once ruled with great power and confidence.

ONCE upon a time so long ago, after the fall of night in a fortress far away, the metal of soldiers’ armour clanked and glowed in the flickering torchlight as traders and travellers from the far corners of the isle of Lanka met and ate and drank and gossiped over a chew of betel beside the hewn stone battlements. As the night grew deeper, one by one they fell asleep, lulled by the soothing sounds of the waters of the Gal Oya rushing over smooth boulders. Perhaps they were occasionally disturbed by the tinkling of a pack bull’s bell or the neighing of a soldier’ s horse.

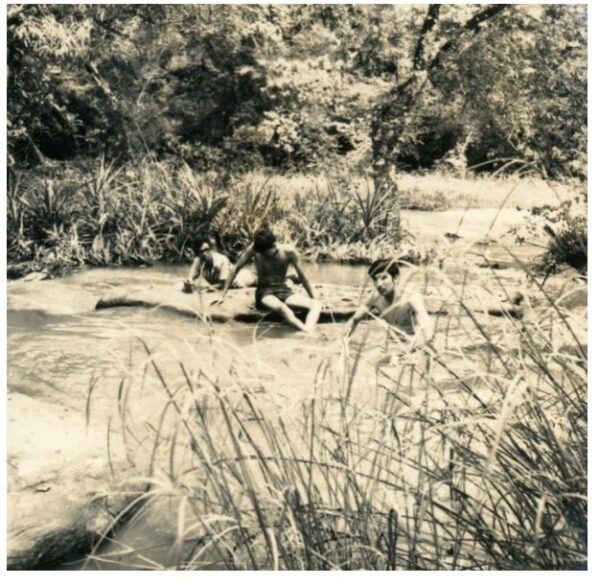

If you spend a moonlit night there today, you will still be lulled to sleep by the soothing sounds of the waters of the Gal Oya rushing over its smooth flat boulders. But if you are disturbed at night today it will be by the trumpeting of elephants or the wild and unforgettable cry of a pack of jackals howling at the moon.

Nilgala lives

—————-

This paean to the Nilgala Frontier is dedicated to my father Prof. Senaka Bibile who explored this region while still a schoolboy at Trinity College Kandy when, during school holidays, he accompanied his father the Ratémahattaya C.W.Bibile on his official circuits of the roadless Wedirata which they traversed by foot and by bullock cart, bivouacking in the wilderness. Later, when I was a schoolboy at Trinity, my father encouraged me to ‘go explore’ the Maha Wedirata which I traversed by foot and by bullock cart just like him. If not for my father, I would have been just another city-bound teenager and missed the life-enhancing adventures of Wild Ceylon.

FOOTNOTES, ILLUSTRATIONS, MAPS

Author’s note: The following entries are not strictly restricted to the above article which is really a paean to the Nilgala Frontier – the heart of the Maha Wedirata.It is not a learned treatise but more of a ‘memoir’ of my travels in the Nilgala Frontier. To make the article more meaningful I have included a variety of photographs from the region taken over many years on many journeys and expeditions. Hence the photographs are not in a strict chronological order as such but are included to illustrate the scenes that I have seen and the adventures that I have experienced in the territory.

Maps are included as they are important to give the reader a ‘sense of place’, as well as to provide some navigational waypoints for future adventurers. I hope you enjoy the maps as much as I do. The write-ups below may even seem a little meandering and disjointed, but bear with me as I take you on a journey to a fascinating area and through some fascinating history.

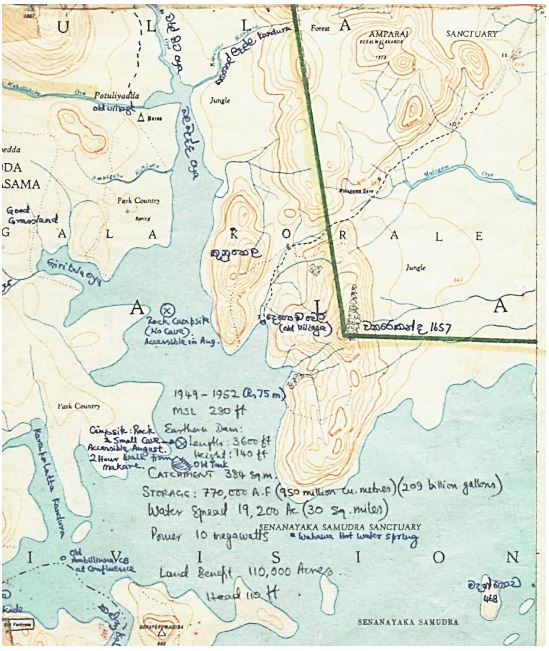

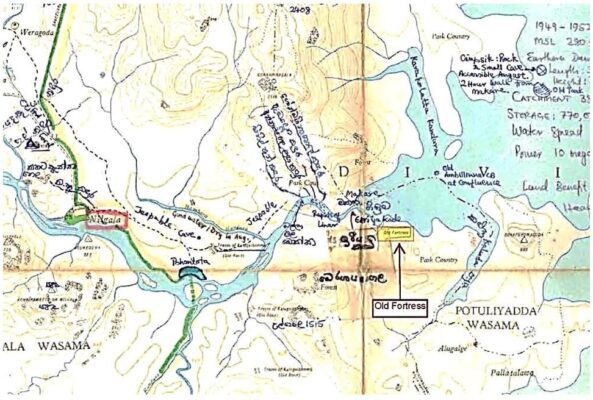

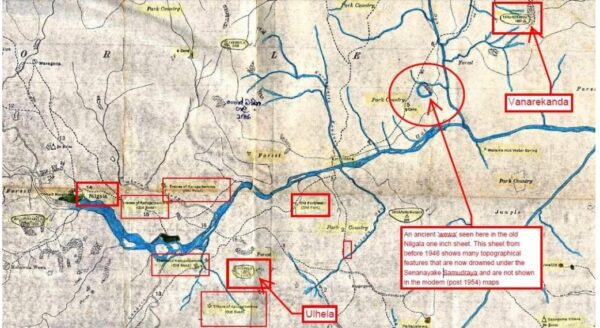

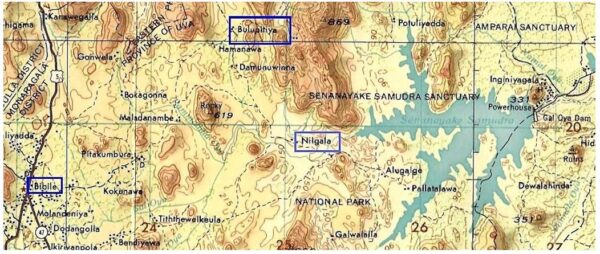

Below: Extracts from the “Nilgala” 1 inch sheet showing the Author’s own annotations for better navigation

Note the information about the reservoir culled from various sources. This is something I have entered on most of my 1”sheets where important water bodies are shown, The blank blue areas of the waterspreads are perfect for this data.

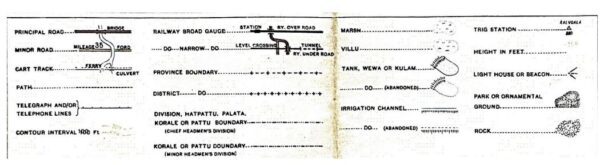

Maps and cartography are subjects close to my heart. The old “1 inch:1 mile” scale topographical sheets of Sri Lanka (no longer in print) are part of my treasured collection. Those 72 sheets, compiled by intrepid surveyors footslogging through the island and its wild places, have far more details on them than the modern maps published by the Survey Department which are mostly based on satellite imagery. An example is the ‘Kalugalbemma’ in the Maha Wedirata about which I explain on Page 16. Another such example of ‘footslogging accuracy’ are the old Yala area maps. They

had useful, maybe even life-saving information, such as waterholes marked “Water in August” (the dryest month). Old explorers and hunters used the information to survive.

That information is needed even today by the Pada Yatra pilgrims. I remember making a journey along the pilgrim path through Yala East during the parched month of July and coming across some emaciated pilgrims almost dying of thirst who begged me for ‘a drop of water’ The importance of waterholes was also demonstrated during an expedition we made through Yala East in search of a lost monastic complex in bear-inhabited caves on a remote rock outcrop called Talaguruhela in the Yala Strict Natural Reserve. We had two official armed escorts from the STF but they drank the water rations too quickly and we had to ration the water ‘by the gulp’ in the last two hours of the return trek through the burning scrub jungle. GPS won’t find you water in the arid jungles, but the old survey sheets can show you where to go if you know how to use a topo sheet and a compass.

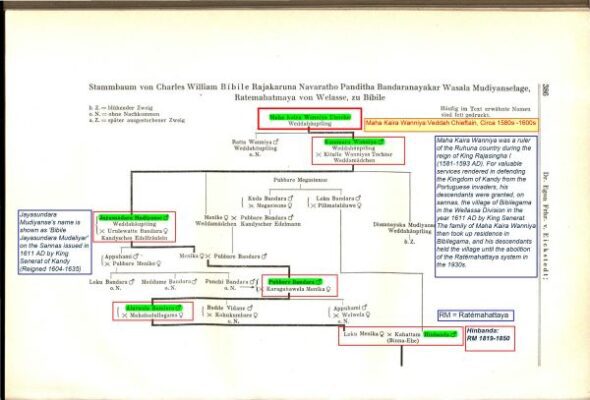

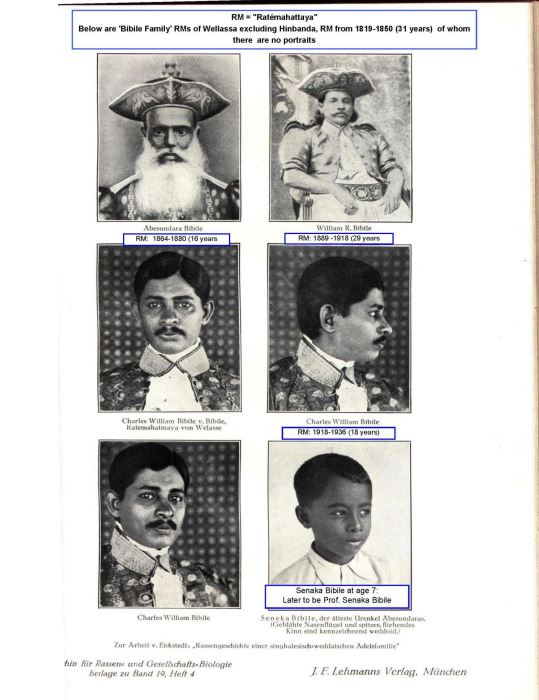

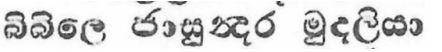

When talking of the Maha Wedirata I have to include my own Bibile Family history which is inextricably linked with the Maha Wedirata ever since the Veddah Chieftain Maha Kaira Wanniya’s family were given the area on a Sannasa by King Senerat of Kandy in 1611 AD. (See Sannasa on page 31). It was a huge swath of the Maha Wedirata given to my ancestors in recognition of that Vedda Chieftain’s valiant efforts to defend the Kandyan Kingdom from the invasions of the Portuguese, and for providing a safe haven for the King and his family and the Kingdom’s wealth during Portuguese incursions. That is detailed in the history-books including the ‘Parangi Hatana’ (Ref Page 30).

The Bibile Family-Veddah nexus is in the document published at the link below.

https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/transfer/article/view/101809

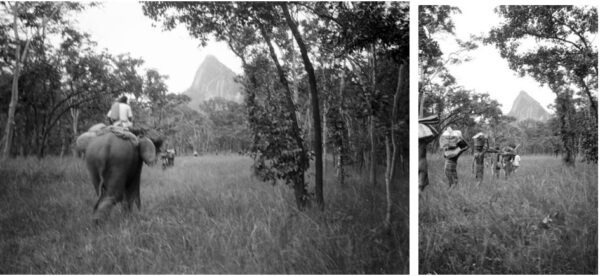

The German anthropologist Baron Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt visited Ceylon, Bibile, Bibile Walauwa, and the Bibile Ratémahattaya C.W.Bibile in 1927 and went with CWB on an expedition into the Maha Wedirata with CWB’s elephant ‘Mudiyansé’, his horse, and 40 porters, carrying 40 tons of equipment and food. After living with the Veddahs in the deep jungles he called them a ‘Noble Race’, something that no Sri Lankan has ever done. He wrote extensively about them and published a book. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egon_Freiherr_von_Eickstedt

More on von Eickstedt, his expedition, research, and book appear later in this article

Below: The Tûn Sinhalé (තුන් සිංහලේ) Map showing the location of Bibile in the Ruhunu Rata of old

In the days of the Kandyan Kings and their Veddah allies, the route from the maritime ‘Roads of Batticaloa’, where the Portuguese anchored their ships, to Kandy, was up the river valley of the Gal Oya past Nilgala and what is now Bibile town, to Mahiyangana near Dambana where Mahaweli disgorges into plains of Bintenne, and from there up the river valley of the Mahaweli into the heart of the Kandyan Kingdom. Members of Maha Kaira Wanniya’s tribe guarded those eastern approaches to Kandy, battling the Portuguese as the Portuguese tried to pass through the inhospitable jungles of the Maha Wedirata along the Gal Oya. Rewarded for their bravery by the King with the lands of the Maha Wedirata, Maha Kaira Wanniya’s descendants settled in Bibilegama (now Bibile) as that area had plenty of water from underground streams coming from the Madulsima Range and emerging as perennial springs (‘bubulas’) at Bibilegama.

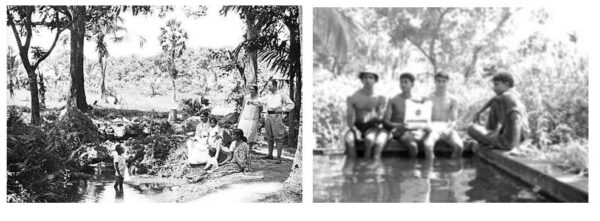

A ‘Bubula’ of Bibile: This one in the Bibile Walauwa garden Left, 1927: Ratémahattaya C.W.Bibile & Family and the von Eickstedts at the spring or ‘bubula’ in the Walauwa

garden Right, 1967: The Author (at right) and friends at the tank built around the same bubula as a constantly overflowing reservoir

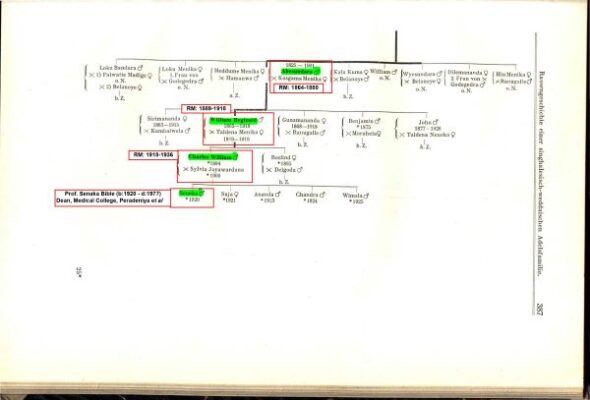

And so, the Veddah descendants of Maha Kaira Wanniya became settled landowners and agriculturists, were appointed as Chieftains, married into the Uva Kandyan Families, built a Walauwa, and ruled the territory. Even after the takeover of the Kandyan Kingdom by the British in 1815, the Bibiles were granted the area to administer as Ratémahattayas and ruled through four generations of Ratémahattayas beginning in 1819.

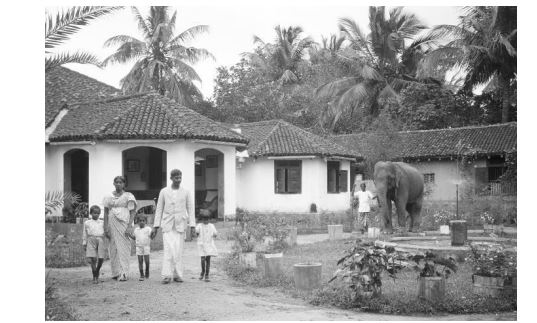

Above: The 4th Ratémahattaya, C.W.Bibile and family, and the Walauwa elephant ‘Mudiyansé, photographed by von Eickstedt in 1927 in front of the new Bibile Walauwa built by C.W.Bibile’s father, W.R.Bibile, the 3rd Ratemahattaya. There was an earlier Walauwa which was described by the German anthropologist Dr. Emil Scmidt who came to Bibile in 1889 and met the 2nd Ratémahattaya Abesundera Bibile and son W.R.Bibile (3 rd RM) at the Parana Walauwa (Old Walauwa).

C.W.Bibile (seated) and minor chieftains dressed in their ceremonial attire pose for von Eickstedt in the Walauwa garden in 1927

von Eickstedt recorded the interesting relationships of the Uva Veddahs with the Uva Kandyans in a paper titled “Racial history of a Sinhalese-Wedda Aristocratic Family” and states, inter alia,

“Among the distinguished Sinhalese families of the Uva district ( Eastern Ceylon) with their extreme proudness of tradition who for many centuries have served the oldest dynasty of the world, several are boasting of a direct descendence from the old aborigines, the Wedda. The rigid and arrogant caste spirit of the old Sinhalese élites just in Kandy (the Ceylonese highland, independent till 1815), who didn´t even regard the inhabitants of the western lowlands with its European colonies completely as their equals, indeed treated the Weddan blood in former times as coequal….in the Eastern parts of the island, the esteem for the Weddas is still directly showing up in common behaviour: the district chief, clad in silken sarong, has to receive orders in standing while the dirty and almost naked Wedda is asked to squat down*. “The Weddas are of high caste.” This behaviour is due to the far-reaching independence that even now is, or has to be, admitted to the few surviving Wedda families, and it is also due to their former position at the court and in the army of Sinhalese kings. This early influence of the Wedda chiefs was based on the great, and often deciding, importance the Wedda troups had for the power and existence of the Sinhalese kingdom as the

following family histories amply show.”

*To the Veddah, ‘squatting down’ is the equivalent of ‘taking a seat’ as an honoured visitor.

I have been fascinated by the Maha Wedirata, and more specifically the Nilgala area, and explored it on foot and by 4WD over three decades, camping out in the wilderness on numerous occasions with adventurous friends, my Uncle Ananda Bibile, and of course with Podiappuhamy of Bulupitiya, my erstwhile tracker in the Wedirata who believed that my wanderlust in the territory was due to my Veddah blood.

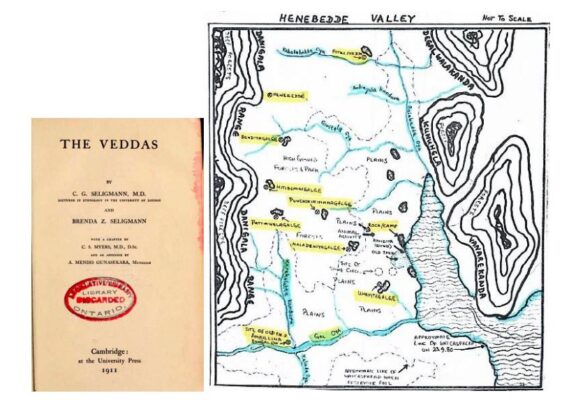

I want to place as much as possible on record, so bear with me. My own knowledge was gained because people of the past, including the likes of Dr. Emil Schmidt (1889), Drs C.G and Brenda Seligmann (1908), and Baron von Eickstedt (1927) visited the Maha Wedirata, Bibile, and Bibile Walauwa, and worked with three generations of Bibile Ratémahattaya from 1889 onwards and made voluminous notes and wrote books and deposited them in museums in Germany and England which were made available to me.

Sitting with my grandfather C.W.Bibile, in the daytime heat and the nighttime lamplight of Bibile, Baron von Eickstedt researched and meticulously recorded the Bibile Family Tree, beginning with Maha Kaira Wanniya. That data has long been lost within Sri Lanka. We have access to it today only because his papers were miraculously saved by von Eickstedt himself during the chaotic days at the end of World War Two with German cities being carpet-bombed. Here is the adventurous story of the Eickstedt papers in the words of my German research colleagues:

“After World War 2 Eickstedt had to flee from Breslau where he had worked and lived and he had to leave all papers there. Later he went back under cover several times to rescue his material and brought it back in sacks and boxes. He kept it in Leipzig first and later brought it to Mainz. Unfortunately, he never worked with the material again. All photos and diaries were found long after his retirement somewhere in the basement of the institute. Finally, it was handed over to the Dresden Museum to my then colleague Dr. Lydia Icke‐Schwalbe, who had kept the connection to the institute for years, and longer than me”

Thereafter the papers were kept safely in German museums and gradually catalogued. I was able to retrieve them with the help and co-operation of dedicated German researchers over a period of three years. They clearly have an amazing system of record keeping and preservation for which we must be grateful.

The Author owes a huge debt of gratitude to several museums in Germany that opened their archival vaults to me, and very specially to two redoubtable German research colleagues from the museums, Dr. Carola Krebs and Dr. Maria Schetelich who doggedly pursued every lead and every document through three difficult years, including the Covid quarantines, to make possible my research, and the article whose link is given on Page 7.

The Bibile Family Tree was compiled by von Eickstedt from elaborate records kept at Bibile Walauwa, including ancient Ola Leaf records in the possession of Ratémahattaya C.W.Bibile. That was in 1927. These records no longer exist with the family. C.W.Bibile died suddenly in 1936 at a young age and in the aftermath, which must have been very traumatic, many papers have been lost. I do remember being at Bibile Walauwa one day in the 1960s and my grandmother, Sylvia Bibile (Mrs. C.W.Bibile), showing me the Ola Leaf Sannasa given to the family by King Senerat in 1611 AD. That too is no longer traceable with us although von Eickstedt says there is a copy at the Badulla Kachcheri. I hope one day to find it at least the copy. The copy in this document is a paper copy from the time of C.W.Bibile, and luckily, I was given the paper copy by my grandmother in the 1960s and carefully preserved by me in my archives.

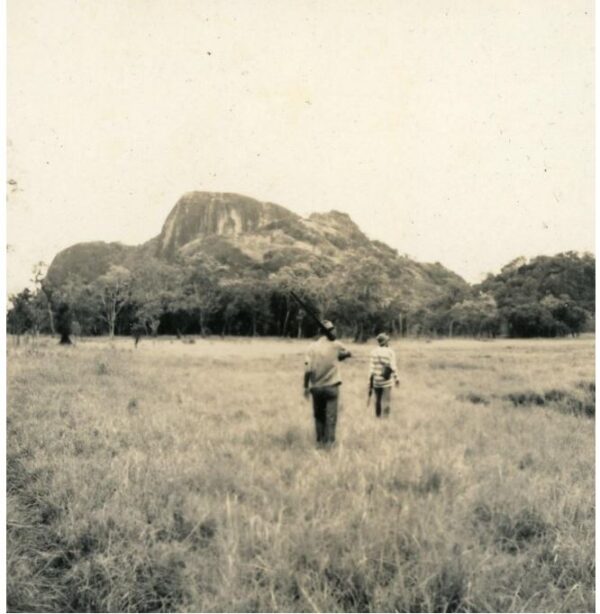

In the Nilgala Frontier

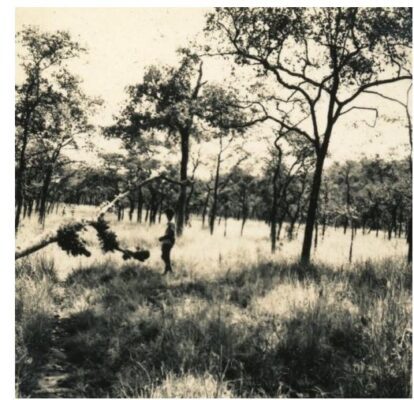

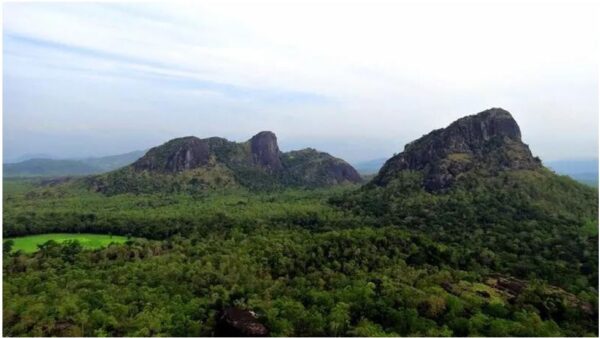

Nilgala talawa – a unique landscape

The medicinal Aralu, Bulu and Nelli trees still flourish in the talawa which is above the waterline.

Sir Emerson Tennent talked of, “open glades and forest scenery….park like meadows and surrounding woods… trees of majestic dimension and pastures through which the deer troops in herds ”

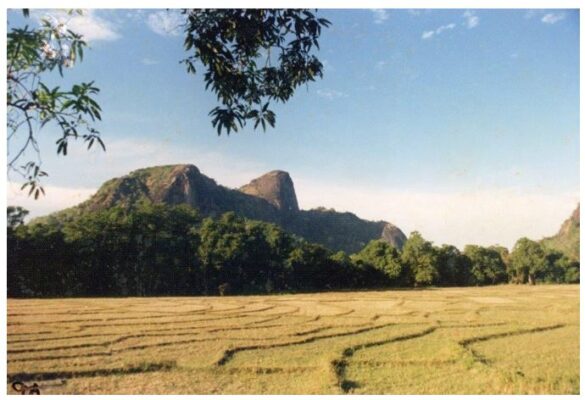

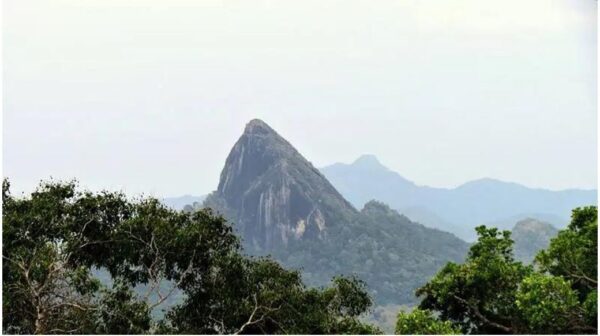

“…overlooking green fields of paddy now worked by the goviyas of Bulupitiya. Across the paddy lies a line of stately Kumbuks along the banks of the Gal Oya and beyond rises the dramatic peak of Nilgalahela (1582 f t – as high as Kandy )

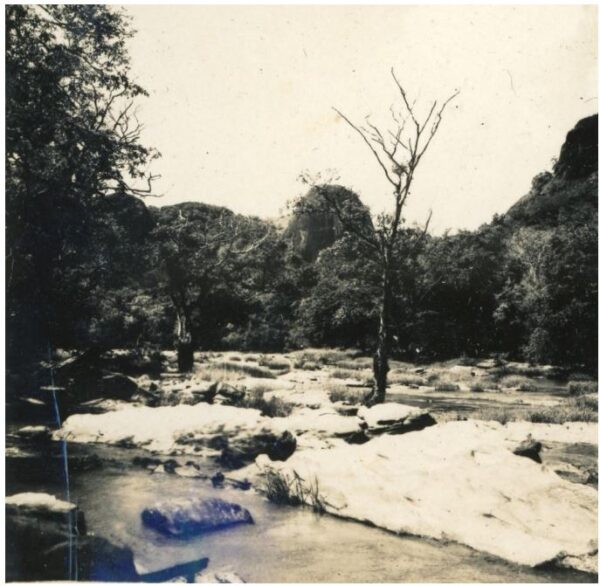

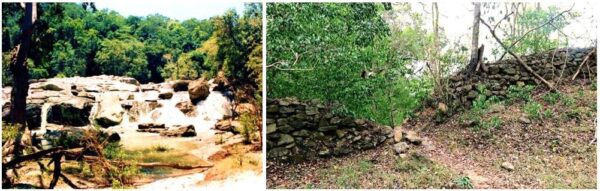

Above and below: “..the Gal Oya, from whence emanates the soothing music of waters rushing over the huge granite slabs of the river, for which reason this spot is called Lokgal Oya by the locals.”

Above: An afternoon’s excursion In the ‘Park Country

Sir Samuel Baker in 1848, “I cannot describe the country better than by comparing it to a rich English park, watered by numerous streams and large rivers, but ornamented by many beautiful rocky mountains, which are seldom to be met with in England. If this part of the country had the advantage of the Newera Eliya climate, it would be a paradise.”

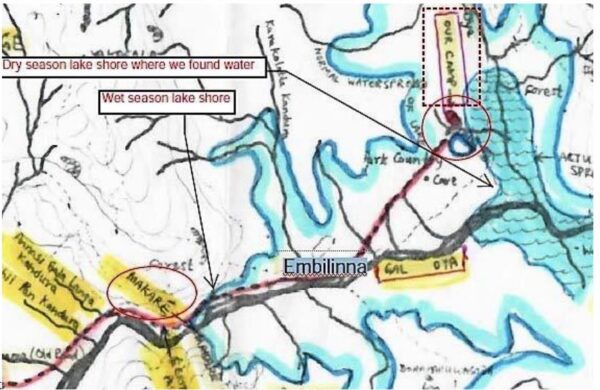

Above: The location of the old fortress, strategically placed at the entrance to the Canyons of Makaré – the ‘Mouth of the Dragon’. The names of the streams not named on the Survey Department’s 1”:1mile map have been entered by hand by the Author, based on his tracker’s local knowledge. The jungle trackers who wander the talawa have names for each and every stream and rock outcrop as they are the navigational waypoints in the trackless talawa.

Below left: Upstream from the Canyons of Makaré there are unnamed rapids, not marked on any map. I gave it a name on my copy of the map for my own reference.

Below right: The remains of the hewn-stone fortress: “It was situated on a rocky rising rib of land between the roaring river and the brooding peaks of Ulhela and Berayahela, and half buried amidst the tumbling boulders and man-high mana grass of this place.”

The Map Legend above shows elements of the intricate data the surveyors captured while traversing the jungles on foot.

The timeless oral traditions of the villagers’ claim the Kalugalbemma to be the remnants of a great highway that ran from the Raja Rata in the north to the Kingdom of the Ruhuna in the south. This feature appears on several of the old 1”:1mile topo sheets of the Survey Department which were compiled in an era when hardworking surveyors traversed the country on foot and recorded each and every geographical feature on the ground. But this Kalugalbemma feature lies hidden under the tall mana grass of the talawa. Modern aerial and satellite mapping simply do not pick it up or show it.

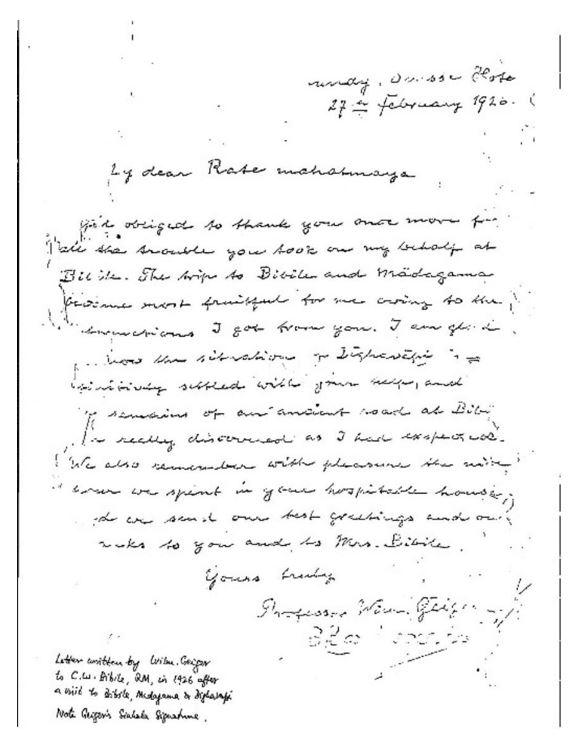

“Wilhelm Geiger, the brilliant linguist who translated the Mahāvaṃsa from Pali into German, travelled to Sri Lanka three times from 1895 onwards. His interest in the historical background of the Dīpavamsa and Mahāvamsa brought him, on his second trip (1925-1926), to Bibile in search of lost notions about the age-old overland trade routes which started from the north of India and went along the Indian west coast up to the ‘Pearl Island’ Sri Lanka, the important center of overseas trade. Geiger, like von Eickstedt, developed a friendship with Charles William Bibile, Ratémahattaya whose intimate knowledge of forest paths helped him – Geiger – to discover the remnants of an old route leading from Anuradhapura through the Ruhuna kingdom down to Tissamahārāma on the southern coast”. (Bibile et al Heidelberg “Return of the Ancestors”).

It was this Kalugalbemma in the Maha Vedirata that the Author’s grandfather, C.W.Bibile, showed Geiger in 1926, for which Geiger was very grateful and wrote the following thank you note to CWB and signed off in Sinhala script.

Above: The Author, grandson of C.W.Bibile, visiting the Kalugalbemma in 1966 with the same safety precautions as in 1926. Note the rounded stones which are the hallmark of the Kalugalbemma. Could these rounded stones have been the base stone layer of a road where the upper layers have disappeared over the centuries, or could this long north-west to south-east aligned stream of rounded boulders be a geological fault of some sort? No one seems to know. Of course, for the old Lankans to build their pyramid sized Dagobas and the great dams, reservoirs and long irrigation canals, they must have had an intricate system of sturdy roads to transport the heavy building materials. In the background one sees the Park Country – the talawa

Above; Anthropologist Dr. Seligmann’s Map of the Henebedde Valley and its Veddah Caves, noted by him during his 1908 Expedition when he was accompanied by Ratémahattaya W.R.Bibile, C.W.Bibile’s father and the Author’s great-grandfather

Above Left: Title page from the Seligmanns’ Book published in 1911. On a mission for the British Colonial Government to study and document the Veddahs, they explored the Maha Wedirata accompanied by the Author’s’ great-grandfather W.R. Bibile in 1908, and WRB is mentioned numerous times in the book. Above Right: The Author’s own hand-sketch of the Henebedde Valley during a low water time expedition to study old Veddah caves and the wildlife. .

“But when the rains are late in the season and the lake low in water, there emerges the ghosts of the lakebed – the desolate cave-homes of the Veddahs and their gaunt granite outcrops,”

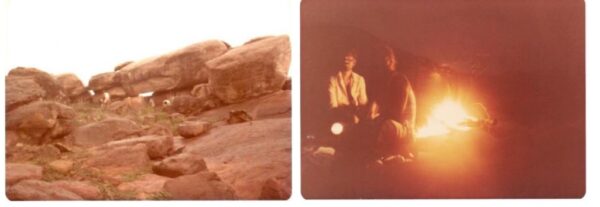

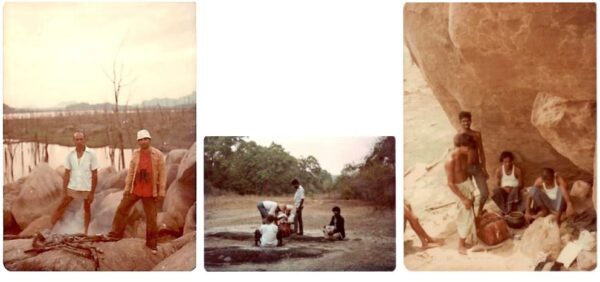

Above left: After the morning tea and ‘pol-roti’, we douse the campfire completely before heading off. Here I am pictured with Podiappuhamy at one of the Henebedde Valley Veddah-Cave camps. As can be seen, the water level is very low, which is the time to explore the history ‘written’ in the usually submerged lakebed

Middle: Our party of six takes a rest break during the trek and re-organises the loads. The party consists of my uncle Ananda Bibile, tracker Podiappuhamy, myself, and three accompanying villagers

Above right: My field note of this day says, “At 11.30 a.m., ravenously hungry after a seven hour-24 km march through difficult terrain, we stop in the partial shade of a rock outcrop to cook a quick lunch with the water we had found. Spiced noodles with tinned meat were the menu” Note the size of the communal cooking pot for six hungry men

Elephants are everywhere in this Park

“..and the signs of man from the Old Stone Age.”

History written on the lakebed”: We came across these stone circles which were about 12 feet in diameter. The stones were not rounded like the ones at the ‘Kalugalbemma’ (See Page 16). The villagers, in their traditions of oral history cum fables, called these circles ‘muthu kelapu tan’ (මුතු ලකලපු තැන්) – places by the old highways (‘Kalugalbemma’ ibid) where the rich played a game of chance akin to the present day ‘Booruwa’. But Dr. Raja de Silva, a former Archaeological Commissioner of Sri Lanka, told the Author that they were most probably burial places pre-dating the practice of cremation before the practice of cremation was brought over to Lanka from India some two thousand and more years ago. He said such stone circles are found elsewhere on the island too. Dr. R.L. Brohier in his book ‘Seeing Ceylon’ states “Dim traditions supported by other evidence associate the Gal Oya Valley with man of the Old Stone Age. This naturally refers to wild untamed Ceylon, long before its history began to be told in lithic record and monument”.

Whether these circles relate to the Veddahs is unknown, though it is unlikely.

A ‘lake under a lake’.

The bund of an ancient ‘Wewa’ (Lake) which normally lies deep under the waters of the Senanayake Samudraya emerges when the Senanayake Samudraya is low in water. We march across the parched lakebed towards the ancient lake’s bund hoping to find water for ourselves inside the old lake. And we did find water, and crocodiles, which prevented us from having a much-needed dip to cool off. Such are the travails of the old Maha Wedirata for those who seek to explore it.

Beyond the old wewa is the 1657-foot Vanarekanda mountain. (See following maps)

Above: The old (pre-1948) Nilgala ‘One Inch Sheet’ shows many topographical features that are now drowned under the Senanayake Samudraya and are not shown in the modern (post-1954) maps. Note the scattered locations of the then known sections of the Kalugalbemma (marked above by the Author in red boxes). More sections were discovered under the tall grasses of the talawa in later years by ‘footslogging’ surveyors and added to the maps (see page 16). Then the Survey Dept switched to satellite imagery and lost many valuable ground features hidden under grass-cover and tree foliage.

Above: The Author’s hand-sketched map of the area from the above mentioned dry-season expedition

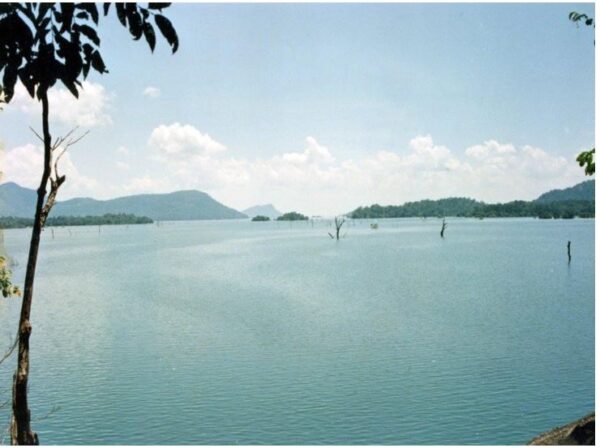

Above: The wet-season views are very different; more scenic and pretty but without the ‘discernability’ of ‘history written on the lakebed’.

“As the pent-up waters rose relentlessly over the many monsoon seasons, they submerged tens of thousands of acres of beautiful earth: The historic lands around Nilgala, of Wellassa, and of the Maha Wedirata, drowned”.

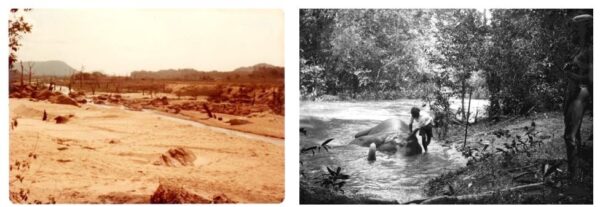

Above: The lakebed in the dry season seen from near the same spot as the full lake was photographed in the top picture.

Above left: The Gal Oya and the lakebed in the dry season, photographed at the location of the old Embilinna circuit bungalow. Above right: Embilinna in 1927 with its luscious riverine forest. The Bibile Walauwa elephant ‘Mudiyansé’, being used for the von Eickstedt expedition of 1927, gets a bath. The flooding of the terrain to create the lake killed off the trees.

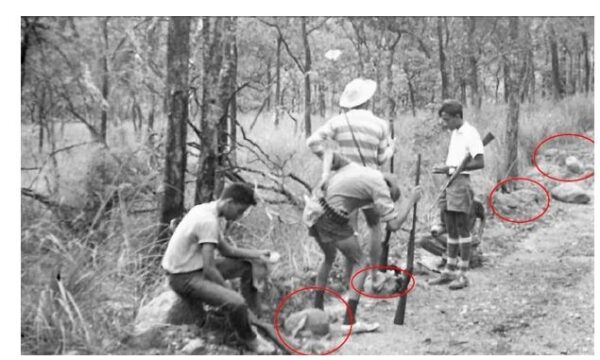

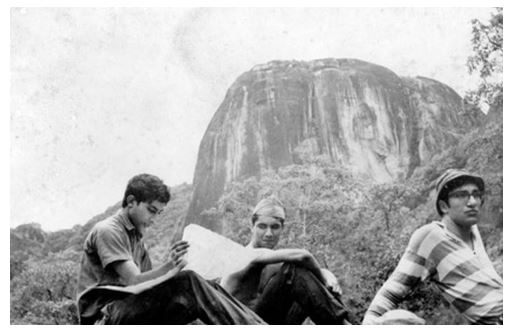

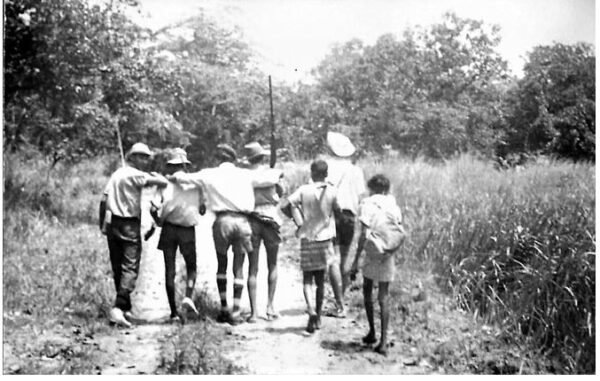

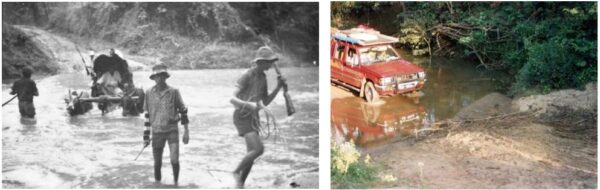

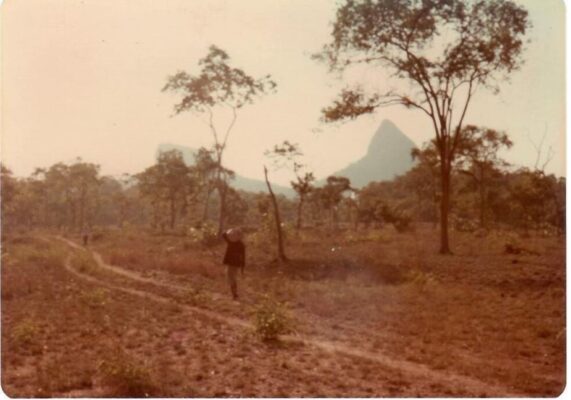

. Above: Camping in the Nilgala Frontier in the 1960s required walking the 15 miles (22km) from Bibile to Nilgala in a day, and total self-reliance in the jungle, including having a thorough knowledge of map readings and compass bearings for accurate navigation, as well as obtaining one’s own food from the jungle.

Above: Camping in the Nilgala Frontier in the 1960s required walking the 15 miles (22km) from Bibile to Nilgala in a day, and total self-reliance in the jungle, including having a thorough knowledge of map readings and compass bearings for accurate navigation, as well as obtaining one’s own food from the jungle.

Above: Reading maps and navigating in an era before GPS was invented. Here, I am studying the 1”:1mile Nilgala Topo Sheet while seated below the brow of Bulupitiyahela (1770 ft) .

Map, compass, axe, gun, rod & reel: Our survival gear in the Maha Wedirata in the 1960s

Trekking into the wilds with a jaunty step

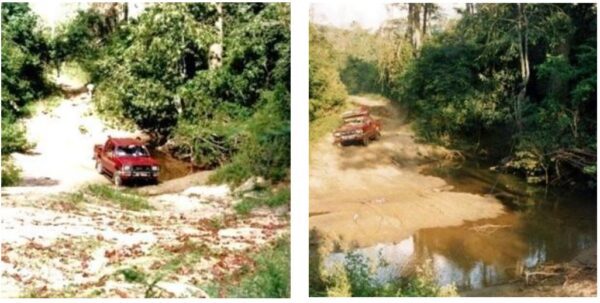

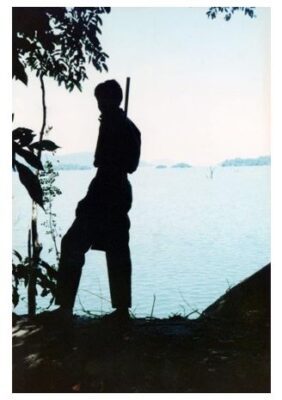

Above: Crossing the Pammedilla Oya, the halfway point on the 15-mile (22km) trek from Bibile to Nilgala: Here seen in the dry season with our tracker Podiappuhamy from Bulupitiya Village bringing up the rear, armed with his trusty 12 bore shotgun. He would not venture out of his home without the weapon. There were several streams like the Pammedilla to be forded in the journey across the well drained talawa to get to the Maha Wedirata

Below: Getting to the Maha Wedirata required the taking of many safety precautions against wild animals, and preferably, when we could afford it, transport of some sort for carrying luggage and provisions as it took the loads off our backs.

Bottom left, Crossing the Pammedilla in the rainy season circa 1966, with a bullock cart carrying the camping gear and provisions.

Bottom right, In 1994, in the comfort and safety of a 4WD with its roof-top sleeping quarters.

There are many streams to cross on the journey to the Maha Wedirata

Above Left: By 1980 there was a bridge across the Pammedilla Oya on the road to Bulupitiya from where one swings right to get to Nilgala Convenient for the villagers of Bulupitiya but bad for protecting the talawa from encroaching chena cultivators. This is my late Uncle Ananda’s lovely old Ford on the newly built Pammedilla Oya Bridge. My uncle insisted on crank-starting the Ford every morning for decades. With the old crank-starting option one never had to worry about a dead battery!

Above Right: We spot a lone elephant which had to be avoided at all costs in the wide open treeless plain as we were on foot. Luckily the wind was in our favour, and if we stayed still till the animal moved off, we would be safe: And we were.

We are headed for Bulupitiya village to meet up with Podiappuhamy and set off by foot to Nilgala and a trek through the Gal Oya National Park. We are armed with my uncle’s licensed shotgun for self-defense, and of course armed with all the necessary permits from the WLD, in return for my providing the WLD with detailed reports on the wildlife, encroachers, and signs of poaching. The poorly funded WLD did not have the resources on the ground for patrolling this huge roadless Park in which solid ground is designated as “National Park’ territory with all the attendant protections, but in which the water surface is merely designated as a ‘Sanctuary’ where fishermen from Inginiyagala are allowed to fish but not to get down from their boats and step on solid ground. A somewhat unworkable set of regulations as the water levels rise and fall depending on rainfall. The fishermen of course ‘go ashore’ and have illegal fish drying ‘wadiyas’ on solid ground – illegal, but to which the undermanned WLD turns a blind eye. But worse is the poaching by fishermen and others. In the 1980s with the war raging, even the underfed soldiers in surrounding camps were not averse to supplying themselves with a little venison or wild boar or even buffalo meat to supplement their rations. And I have seen animal carcasses stripped clean to the bone and cartridge and bullet casings on the ground nearby and reported to the WLD who could do precious little to curb that poaching.

Above: The Nilgala Frontier is where the avifauna of the dry-zone, the wet zone and the mountain zone co-mingle.

It is a paradise for ornithologists.

Above: In the 1990s, the Wild Life Department would provide an armed guard for protection during my foot-expedtions into the Nilgala Frontier and its Gal Oya National Park, whereas, in the 1960s, the Author and his fellow exploreres were free to carry their own licensed firearms into the territory.But after the JVP uprising of 1971, that was forbidden.

My faithful tracker Podiappuhamy (seen here in a turban) in the back of my 4WD in the Nilgala talawa. Podiappuhamy disliked vehicles and preferred to walk in the talawa with his loping-rolling gait and could cover about 5 km per hour on foot.

On one occasion I hired a tractor-trailer to go to Nilgala as the excursion group had weaker, less fit members. Those who know, know, that there is no bumpier ride than in the trailer of a tractor. After an hour, Podiappuhamy said he’d rather be thrashed by a wild elephant than go again in such a contraption !

This hardy soul, to whom I could entrust my life in the wilds, passed away before the end of the millennium, about the same time I was exiting Sri Lanka for good. With his passing, there died a body of knowledge that was irreplaceable. The younger generation, in my own experience, have no knowledge to navigate these still somewhat trackless forests, and have no jungle survival craft worth talking about.

The Maha Wedirata

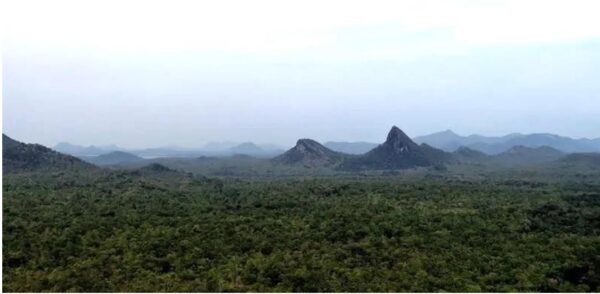

Above is a general contour map of the Maha Wedirata showing points of interest and some of the dramatic peaks and valleys, and the overall terrain which made it inhospitable to both the Sinhalese and the foreign invaders. Even the British Colonial power left the Veddahs alone but gave them special privileges; one of which was the right to grow marijuana for their own consumption, an activity that could land any other Sri Lankan in jail.

The wild terrain depicted in the above map is seen in the following photographs. This territory is where the Veddahs gave refuge to the Kandyan Kings. None of the invading western armies dared to venture into this wild landscape guarded by the Veddahs.

Wild terrain: The Maha Wedirata

“So the Wedda were powerless in the kings territory and the king was powerless in the wedda territory. Out of this specific and strong relations developed which could be described as a social symbiosis.”

– Baron Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt, 1927

The dramatic peak of Ulhela (1515 ft) dominates the scene as it soars above the surrounding jungle plains.

Anthropologist-explorer Baron von Eickstedt who visited Ceylon, Bibile, and Bibile Walauwa, and befriended Ratémahattaya C.W.Bibile in 1927, states, quoting parts from the Parangi Hatane et al:

“And yet these ‘backward’ people … were among the most faithful servants of the King. To the Veddahs of Wellassa it is said were entrusted the King’s treasures, twelve of them being chosen to be the custodians and invested with silver girdles and canes embossed with silver, and a special dress to distinguish them from their fellows. They would stealthily enter the palace at night and interview the King when they desired orders on any matter affecting their charge.”…

“When pressed hard by the invasions of the Portuguese which were soon to follow, it was to them that the King used to entrust the Queens, and they would shelter them in temporary huts, brightly adorned with greenery according to Sinhalese custom, constructed in the dense forest which stretched for fifty miles” ….

“Later, under distress by the Portuguese the king would entrust them the queens who would be protected by them in an area of deep forest between Welasse and the first row of Batticaloa mountains. So the Wedda land was in a way the last refuge of the Singhalese kings.” – “And our King could no longer stay in the city, had no strength for the fight – but with his family, his precious gold and precious stones, with his slaves and his files and treasures – King Senerat then sought refuge in the districts of the Weddas, that was because his fame was darkened and his (religious) merit unsuccessful – and the courage of the men melted like wax in front of the flame of the imperious enemies of the Franks

For services rendered to the Kandyan Kingdom in protecting it from the Invading Portuguese during the Reign of King Rajasingha I (1581-1593 AD), King Senerat of Kandy (reign: 1604-1635) granted vast tracts of land in the Maha Wedirata on a Sannasa to the descendants of Veddah Chieftain Maha Kaira Wanniya in 1611 AD, starting with

It was the beginning of the ‘Bibile Family’ settling in Bibile in the Wellassa region of the Maha Wedirata.

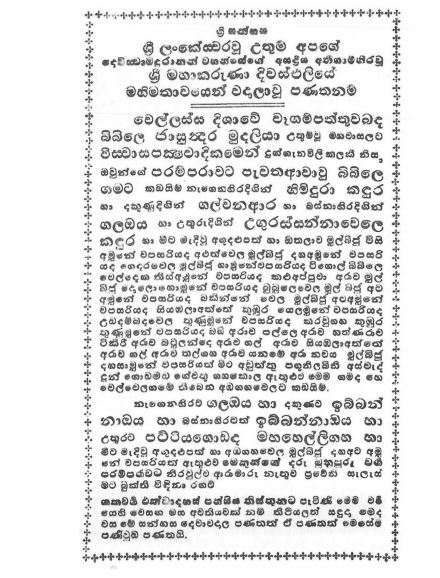

The Sannasa of 1611 AD

English translation of the Sannas

Note:

The Saka Era is believed to have been founded by King Shalivahana of the Satavahana dynasty in India. The year the King was crowned was made year zero. This is believed to have been 78 AD. Hence one adds 78 years to the Saka Era to compute the corresponding year for the Christian Era, i.e. The ‘AD’ year.

Hence 1533 Saka is 1611 AD

The little patch of paddy at Nilgala, surrounded by the wilderness of the Maha Wedirata

Seen from Inginiyagala: Parts of the Maha Wedirata drowned under the Senanayake Samudra. The dramatic wild peaks are seen across the water in the hazy distance. Even today, it’s a mysterious land, probably visited only by a few people as it is still mostly inaccessible and remote and far from comfy hotels.

Above: The Author’s view of Ulhela on one of his expeditions to the Maha Wedirata. Fire destruction like this happens in the dry season.

Above: Two photographs from von Eickstedt’s expedition of 1927 shows Ulhela dominating the route.

The left photo shows Ratemahattaya C.W.Bibile’s family elephant ‘Mudiyansé’.

CWB also lent the Walauwa horse to von Eickstedt. The elephant and horse (and even the Ratemahattaya’s palanquin or ‘Dolawa’) were more useful means of transport in the trackless terrain than any car of that era.

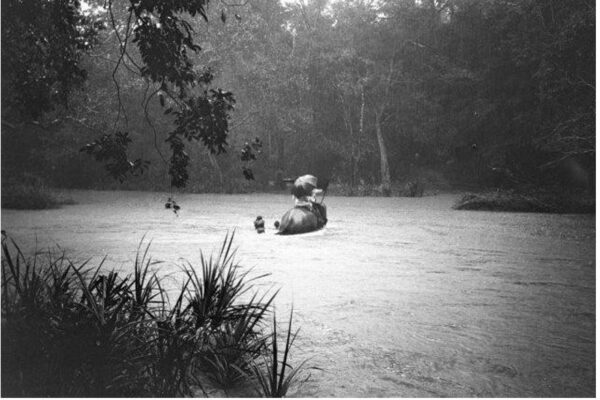

‘Mudiyanse’ crosses the swollen Gal Oya with humans from the expedition clinging on

von Eickstedt wrote in his field notes, inter alia: “ After a 3‐hour march through park jungle, the ford of the Gal Oya was reached. Underneath the deeply down‐hanging trees the murky gurgling waters flowed hurriedly and soaked the trunks, from the small islands, only bushes stuck out. Therefore, the horse had to be sent back to Nilgala, and the elephant under the Kovala was the first to steadily cross the stream. Then he had to cross the river six more times, under the heavy burden of our luggage – while the Haute Volée of the exped. (incl. servants) swang itself on his back and the porters, paddling at his side, clinched to the ropes as well as to his ears and tail. Three, among them the headman of Hamatulla with his picturesque cloth (he was Shikari and guide of the exped.), dared to cross the river swimming.: “

Mudiyansé at the Bibile Walauwa with RM C.W.Bibile and two of his sons Senaka (later to be Prof. Senaka Bibile) and son Ananda seated on top (in 1927)

THE VEDDAHS:

From Brave Warriors who defended the Kingdom from European superpowers, to

inconsequential nobodies in post-colonial Ceylon.

Much learned treatises and books have been written about the Veddahs, but I want to connect some different dots.

Above: The dam at Inginiyagala that drowned the Maha Wedirata and destroyed millennia old history and homelands.

Truth to say, my own feelings about the Dam, the Samudraya, and the Gal Oya National Park are conflicted. It is a beautiful lake, and the National Park is a great habitat for wildlife. But we need to take cognizance about what we, as a nation, did to the Veddahs. Too often we hear Lankans lamenting about what happened to indigenous people on the other side of the planet with nary a thought for our island’s own indigenous people. In Canada such indigenous people are called First Nations because ‘they were here first’. Canadian First Nation get numerous benefits including royalties from minerals or resources extracted from their traditional lands; resources such as oil and forestry products, and other revenues including tourist lodges in their homelands. They also have traditional hunting and fishing rights in areas where non-First Nations cannot enter, hunt or fish. In Sri Lanka on the other hand, Veddah lands have been appropriated not only by other people but also by the Government and turned into National Parks (Gal Oya, Maduru Oya, et al) into which the Veddahs are forbidden to enter. The Government makes money from Park Entry Fees but don’t give even one Rupee to the traditional owners of the Land who live in poverty. All that must change, and Canadian models can help.

To get back to a little history:

Baron von Eickstedt addressed several issues in his book:

For example, Eickstedt quotes Paul E. Pieris in his book about the Portuguese era based on the Singhalese Parangi Hatane chronicle. (Bold emphases below is by me):

“the Wedda land was in a way the last refuge of the Singhalese kings.” .

“King Senerat then sought refuge in the districts of the Weddas.. Kumara Wanniya, the youngest son of Maha Kaira Wanniya of Morane, later married the daughter of another Wedda chief. His two sons fought under different Singhalese kings against the Portuguese and later against the Dutch. King Senerat gave them the title and authority of a Mudiyanse. In times of peace Mudiyanse were the high officers of the palace guards. In times of war they would have to recruit the weapons and capable team of their feudal area and lead them against the enemy. Normally only Singhalese noblemen would become Mudiyanse…. When the king recaptured the fort of Batticaloa from the Portuguese yet another Bibile Mudiyanse was mentioned who had excelled in the battle….the kings on Kandy in their history had to seek alliances against all kinds of enemies, starting with the Tamils threatening them from the north, later European intruders at the West coast. The Wedda served as irregular rifle corps (Schützenkorps) and were useful because of their touching loyalty as guardians of the treasures

and women of the king.

In another section von Eickstedt states: “So the Wedda were powerless in the kings territory and the king was powerless in the wedda territory. Out of this specific and strong relations developed which could be described as a social symbiosis.”)

“It was during the so called Kandyan rebellion when the Wedda for the last time fought for the freedom of the King of Kandy. The rebellion started in 1817 in the province of Uwa which had never seen a foreign ruler before. It was organized by the head of the province the Dissawa of Badulla. According to the lore and family tradition the then

very young Ratemahatmaya Hinbanda of Bibile who was subjected to the Dissawa of Badulla is said to have played an important role in it. He was a descendant of mentioned Jayasundara who himself belonged to the chief clan, the Mahabandaralage of the Wedda. Till today they live very close to Bibile. These are the Danigala Wedda who could be visited with the help of the Ratemahatmaya. They still keep loyal family connections with the house of Bibile like Hinbanda did in the past. Hinbanda lead his troops to Badulla. There he met the British resident Wilson. Today there is a monument at the spot where Wilson was killed by the arrows of the Wedda. The war continued until 1822 and devastated the whole area. The Bibile family members turned to their fiefdom after

having spent time with their relatives, the Danigala Wedda who had found refuge at the Danigala Rock. Four fifth of their territory was lost”

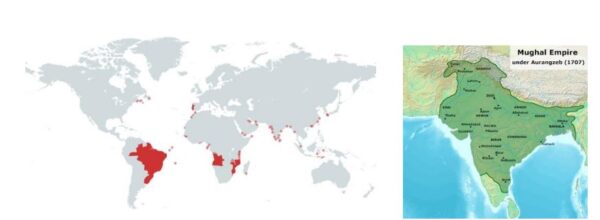

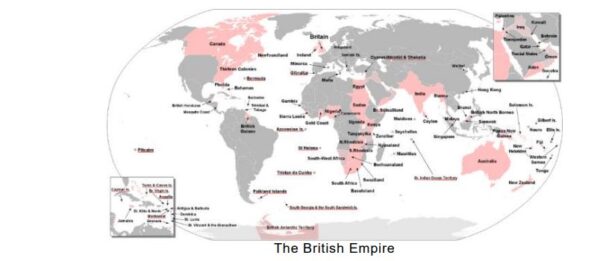

For 200 years these so called ‘backward people’, the Veddas, fought and repulsed three European Superpowers of those eras – the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British, protecting the eastern flank of the Kandyan Kingdom while those same superpowers conquered huge swaths of territory across the world.

The Portuguese Empire (Left) and the Mogul Empire, (Right)

Even the inexorable southward expansion of the mighty Moghul Empire towards Ceylon came to a halt when the Portuguese landed in Goa. Such was the power of the Portuguese that the Veddas stood up to.

Sadly, the brave Veddas who evicted three European superpowers through two centuries, and whom von Eickstedt called a ‘noble race’ and whom the British treated with respect and privileges, were themselves evicted from their homeland by the Ceylon Government within five years of Ceylon getting Independence from the British Empire.

Writer/Author Gamini Punchihewa who worked for the Gal Oya Development Board in the 1950s wrote of pathetic scenes where the Veddahs, the First Nations of Ceylon, were evicted by force, weeping and in a state of shock, from lands they had lived in for millennia before the Sinhalese came to the island from India.

Racial history of a Sinhalese-Wedda Aristocratic Family

If two populations live close to or even mix up with each other for a longer period of time, mixed marriages are inevitable to occur, and this, necessarily, had also a considerable impact on the cultural expressions of the resp. more civilized nation. Soaking up the mentality of another people leads to a reshuffling and tensions within one´s own nature. This might be particularly the case if there is a considerable distance between the two populations in terms of their cultural habitus and also, in case the more primitive gets the opportunity to infiltrate the higher levels of the more cultured people. Examples from the history of great nations like Romans, Arabs or medieval Portuguese show that such racially determined biological impacts on the cultural history of certain nations and social strata are not as rare as one might possibly expect, considering the extrinsic similarity of the respective cultural complexes.

Particularly interesting, but much lesser known is it, that these phenomena can also be found in India – the country of allegedly rather rigid caste systems. The severe caste mentality of the Indian conqueror people knew numerous exceptions, and these have strongly influenced the biological consequences of social seclusion. Within the whole large complex of territories occupied by Indian monarchies, the relationships between the Aryan or Dravidian master peoples and the oldest, i.e. the Weddoid strata of society are exempted – in surprising like mindedness – from the customary integration into caste hierarchies. The most ancient lords of the land were somehow standing outside the caste system and not regarded as impure by the higher castes of the conquerors. This created the possibility for blood of the always very primitive aborigines to seep in – a possibility made much more difficult for the low castes of their own civilized population.

Reliable evidence for such blending processes between primitive and culture people which could certainly find the interest of racial as well as cultural science is currently almost absent from literature . Each and every such case, due to the differences in somatic and psychological

disposition of both components, would needs have to be examined and judged separately. Thus, a vast and productive field for racial studies opens here.The following modest notes will select only a few single cases from the author´s most familiar field of work. However, these modest notes have one big advantage: the genealogical and historical source material on which they are based are well guaranteed – a rather large part of them has been made available to me due to the kind interest of my friend C. W. Bibile, Rátemahátmaya of Welasse, and I would like to use this opportunity to once more express my gratitude for his interest and cooperation. Due to the special nature of the material it became necessary to check it on the spot, that is why I spent my few days of rest after an exhausting crossing of the jungle woods of East Ceylon with writing down of these data.

Among the distinguished Sinhalese families of the Uva district ( Eastern Ceylon) with their extreme proudness of tradition who for many centuries have served the oldest dynasty of the world, several are boasting of a direct descendence from the old aborigines, the Wedda. The rigid and arrogant caste spirit of the old Sinhalese élites just in Kandy (the Ceylonese highland, independent till 1815), who didn´t even regard the inhabitants of the western lowlands with its European colonies completely as their equals, indeed treated the Weddan blood in former times as coequal. In our times, however, this is true of the old Kandyan families in certain limits only, and it is even less true of the nobility in the Western lowlands. These nowadays regard the Weddas as not more than a last heap of miserable “savages” on the verge of dying out. Yet in the Eastern parts of the island, the esteem for the Weddas is still directly showing up in common behaviour: the district chief, clad in silken sarong, has to receive orders in standing while the dirty and almost naked Wedda is asked to squat down. “The Weddas are of high caste.” This behaviour is due to the far-reaching independence that even now is, or has to be, admitted to the few surviving Wedda families, and it is also due to their former position at the court and in the army of Sinhalese kings. This early influence of the Wedda chiefs was based on the great, and often deciding, importance the Wedda troups had for the power and existence of the Sinhalese kingdom as the following family histories amply show.

Even in th early years of the rule of King Rajasimha I. (1571-1592) the later 18 Wedda districts of Ruhúna – today´s Ùva- and Batticalóa district – were independent from Kandy, while the northern Wedda districts had already for a long time been under nominal Kandyan rule. The occupation of the country by Rajasinha led some dissatisfied chiefs to emigrate. According to a

reliable tradition written down in document form already at the time of his grandson, M á h a K á i r a W á n n i y a of Moráne Wátta1 was also among these dissatisfied persons. He had a kind of permanent residence at the foot of the Moráne mountains in Binténne, the remnants of which are shown even today,. After a long stay in Damánegama, in the far North-East of today´s Nilgála Kórale, he left his eldest childless son there and with his second son K u m á r a W á n n i y a of Welássa 2 returned to the area of today´s Bibile. There must have happened a complete reconciliation between king and Wedda prince, because soon after, the names of both sons are found among the names of guardians of the royal treasure. P i e r i s, in his voluminous history of the Portuguese Era in Ceylon 3, relying on the original old Sinhalese source Parángi Hátane, describes the Wedda as in the following way:

“ And yet these backward people….. were among the most faithful servants of the King´s treasures, twelve of them being chosen to be the custodians and invested with silver girdles and canes embossed with silver, and a special dress to distinguish them from their fellows. They would stealthily enter the palace at night and interview the King when they desired orders on any matter affecting their charge.”

From this report the great independence on the one side, and on the other the eminent trust in the Weddas who even today are regarded as reliable is clearly evident. The same can also be inferred from another tradition, describing the immediately following unfortunate historical period of the Sinhalese rule:

” When pressed hard by the invasions of the Portuguese which were soon to follow, it was to them that the King used to entrust the Queens, and they would shelter them in temporary huts, brightly adorned with greenery according to Sinhalese custom, constructed in dense forest which stretched for fifty miles between Welásse and the first range of Batticalóa hills, a region into which the Portuguese never succeeded in penetrating.”4

1 M á h a means „the Great, the Elder”; K á i r a is even now a widely met Wedda name; W á n n i y a is the medieval term for chief and up to this day in favourite use as title, and M o r á n e is the name of the most distinguished Wedda clan.

2 Welássa means „land of the thousand stripes of ricefields“, a very ancient name pointing to former wealth and it is used even today to denominate the district of the Rátemahátmaya of Bibile, although for already thousand years the land is covered by dense forest jungle.

3 P i e r i s: Ceylon, the Portuguese Era….. 1505.1558. Vol.I, Colombo 1913, 327

4 Cf. P i e r i s , op. cit. I, 329

In times of emergency the Wedda land had been the last resort of Sinhalese kings. When after countless atrocities Kandy, too, fell into the hands of the Portuguese, the king was forced to flee:

“ But with his family, his juwels of gold and his gems, his slaves

and records and his treasure chests,

K i n g S e n e r a t s o u g h t r e f u g e i n t h e P a t t u o f t h e W e d d a h s, for his glory was dimmed and his merit had failed.

And the heart of the man melted as wax before the flame of the fierce Parangi foe.”5

Kumára Wánniya, the younger son of the Wedda chief Máha Káira Wánniya of Moráne who had gone to Bibile, got married to the daughter of another Wedda chief, whose name is not known. Under the command of different Sinhalese kings his two sons participated in several campaigns against the Portuguese and later on against the Dutch and were awarded the title

and office of a Mudiyánse 6

by king Sénerat ( 1604-1632, see above). At the same time, both

brothers were simultaneously, i.e. on legal grounds at first the elder, J a y a s ú n d a r a M u d i y á n s e (see family tree), entrusted with the hereditary fiefdom of the villages Bibile and Alanmulla, and a royal document was issued to confirm it.

This royal document, written by steelpen on strips of prepared Tálipot leaves, is today preserved in the archive of the British Registry in Badulla under Nr.5, a reprint being in possesion of the author. Even nowadays the village Bibile belongs to the progeny of the old Wedda prince and the lines of this note are written in the Waláue (aristocratic residence) of his great-grandson in Bibile.

The following details, being of interest for the racial history from the early period of the Bibile family, may be given here. In the Arangá Palace in Wegáma, “where the daughter of the Batticalóa Wánniya was the Queen of the King” (evidently, the king had different wives in his different palaces), a Bibile and a Kaudélle Mudiyánse had the command over the royal guards (again a typical Wedda office!). From this report we also see that the wife of the king (we are

5 Párangi Hátane: cited after P i e r i s, op. cit. I, 417. Párangi = Portuguese.

6 In peace times, the Mudiyánse were higher officers of the palace guards, while in war times they were charged with deploying the people of their fiefdom capable of bearing arms and with marching against the enemy in lead of them. This is, so to speak, a typical Wedda office, but clad in a high position, connected with dignity and fiefdom, both usually granted to especially excellent, but mostly Sinhalese nobles only.

talking about Wimalla Dhárma Súriya I., 1592- 1604, the 172nd ruler of the Sinhalese) had been the daughter of a Wedda prince, i.e. the Wánniya of Batticalóa, and that, consequently, also Wedda blood rose up into the royal family.7 The Sinhalese chronicle further states that during the reign of King Sénerat (see above), when he resided in Mayangáne, a Bibile Mudiyánse was appointed as one of the guards for the young prince Tíkiri Bándara (the later king Rajasinha II., 1632 – 1684). When he himself (i.e. Rajasinha II, M.S.) during his reign recaptured the fort of Batticalóa from the Portuguese, a Bibile Mudiyánse who had excelled in battle was endowed with two Portuguese as his slaves – a fact that is also not without interest in terms of racial science. Furthermore, to the great favour that just the Bibile Weddas enjoyed at the royal court can the fact be traced back, that it had been the daughter of an Urulewátte Adigar – i.e. of a senior minister from an ancient Kandyan family – who, on royal command, had been married to the Jayasúndara Mudiyánse of Bibile. In any case, the reliable and influential Wedda prince, himself belonging to the most distinguished – the “royal”- Wedda clan, should in this way be bound more closely to the throne. With the same purpose in mind, he might have given his sister into marriage to the court noble Pubbáre Bándara.

Anthropologically speaking, these marriages are important because they vouch for when and how noble Sinhalese blood got into the purely old-Weddid Jayasúndara and, vice versa, Wedda blood was received into the Sinhalese noble family of the Pubbáre Bándara. Thus, the descendants of both families were both half Weddoid, half Sinhalese and, biologically speaking, both descendants of Máha Káira Wánniya. This is important because with the childless grandchildren of Jayasúndara, the first male line dies out, and Pubbáre Bándara Káragahawela (also a grandson of Jayasúndara) who by cousin marriage (through which no fresh blood from any side comes into the family) continued the old family tree, biologically as well as legally, by adopting these three childless grandchildren (see family tree).

Thus, this old Wedda family had preserved its purity for three generations and in the fourth to fifth generation had become half Sinhalese. In the seventh generation the male line again extinguished, but was continued biologically and legally by cousin marriage of Lóku Ménika with Kaháttam Hínbanda. Because the husband went over to settle in the house of his wife, this

7 This was by no means the first time. Already Wijéya, the banished viceroy of Gujerat in Northern India, who later became the first Sinhalese king (543-505 B.C.), had married a Wedda princess. Her and her children´s unfortunate fate has been recorded in the Great Chronicle of Ceylon”(cf. W. G e i g e r, The Mahavamsa, London 1912, Chapter VII, pp. 55-61) and is mentioned also in most of the popular history books on Ceylon.

marriage was called Bínna-Ehe. Then,in the sixth till eighth generation only Sinhalese names are found among the married-into families. But because almost exclusively all these families belong to the old nobility of Eastern Ceylon it seems quite unlikely that they should n o t contain Wedda blood. It merely can´t be made out to what degree this was the case.

Since the last century, that has seen the final decline of the Wedda people and at the same time the downfall of the old kingdom of Kandy (probably not coincidentally), among the higher families such kind of intermingling with the Weddas seems to have ceased. More and more – with continually improving economic conditions – Sinhalese settlers inserted themselves in the old Wedda territories. At first only being labourers for the Weddas, soon they easily got ownership rights in the vast jungle areas where land was so cheap. And although nowadays both parties deny any mixed marriage, anthropological inspection, the Registry lists and casual crossexamination test to the contrary. But the new mixture seems to have concerned only the lower strata, i.e. the lower Wedda clans and the lower Sinhalese castes. There is no doubt that such a kind of mixture has existed earlier, too, if only not in such relatively large scale as it is nowadays happening among the remaining tiny Wedda groups. The race mixtures during more than two millennia easily explain why, as it was evident during my expedition, a unification of the archaic Wedda features in one individuum today (and also during the whole period from which we have pictures of Wedda people) has been extremely rare.

Based on the report of a mixed race Wedda, Lewis 8 describes the fusion of Weddas in the Westminster Abbey area which formerly had around the old Góvind-Héla in the Máha-Wédi Ráta (Great-Vedda-Country) been a main area of the Wedda: “….his grandparents belonged to a clan….who lived in a wild state in the Lenama forests, but in time those who survived of this clan became reconciled to their Sinhalese neighbours, and at last came to associate with them and ultimately, by marrying and intermarrying, they abandoned their forest life and settled in and aroud Salawe, or Hallowa Rata.”

Among papers recently shown to the author by chance in the Registry in Bulupítiya (Nílgala Kórale) were several Sinhalese-Wedda mixed people listed by their names. For a systematic study of this process of intermingling it would be now the most opportune time and also a last

8 Lewis, F.: Notes on an exploration in Eastern Uva…Journ. Ceylon Branch R.Asiat.Soc. 1914,XXIII, No. 67, pp.276- 293, 10 Taf., Colombo 1916

possibility. Unfortunately time and financial means of my expedition prevented working in this direction.

The family tree of T a l d é n a M é n i ka might serve as an example how the old noble families of Eastern Ceylon are interspersed with Wedda blood from the long lucky times of this people and, moreover, how the marriages in the country itself – which were absolutely normal – can be taken in a very limited way only to represent a further racial sinhalesization of lineage. She is the wife of William R. Bibile, the head of the ninth generation of the lineage and the mother of Charles W. Bibile, the current family head, who, like his father, grandfather and great

grandfather, holds the office of Rátemahátmaya (District Official or Administrator) of Wélassa.

There is also a Wedda chief appearing as the primogenitor of the family of Taldéna Ménika: Nádena Kumára Vánni Unnéhe.9 His office had been near Bókotuwewátte in Wáttekélle, in the high mountains north from Bádulla (the provincial capital of Uva), where nowadays since long no Weddas are living any more. He got married to Ponnára Bándara Galagóda, a girl from a noble family (as the name Galagóda tells, i.e. roughly “von Felseneck”). She had been “at the court of Kumára Sínha, Prince of Uva, at Bádulla”10 and should therefore have been a kind of lady-in-waiting, married to an officer of the Palace Guard.

The names of the offsprings of this couple, the First Parents of the Taldéna family, are immediately and exclusively Sinhalese. This is regularly true for all cases known to me, and this makes genealogical research more difficult. The extremely long names and richly adorned titles here, mostly shortened without changing the meaning, are an additional difficulty, as is also the extremely frequent use of the same first names. But again, this latter circumstance makes the titles valuable for identification, although even they are rather variable and changed several times during the lifetime of a person. Sometimes, in the closest family circle, individuals bearing the same name – and this is happens rather often with siblings – were distinguished by loku = big and punchi or hin = small, as can be seen from the family trees. That the personal names had played a rather minor role could already been inferred from the historical data for the Bibile family, where all chronicles only talk of “the Bibile Mudiyánse”. This genealogical problem holds also nowadays true for the Weddas. Very often they are not able, even with their

9 Vánni = Wánniya = Wedda chief, Unnéhe = general title, such as „His highness”

10 Genealogical table of the Bibile family, p. 52, M.S.

best and honest will, to exactly tell the name of their wife, their mother or just their own name, and they sometimes are only properly determing it after having asked their fellow tribals. It often also happens that they change their names: thus, e.g., the Vidáne (chief) of Hénnébedde, Poromóla11 simply took the name of the first husband of his second wife, i.e. Síta Wánniya.12 On the other hand, they recount for you subito and without hesiting the most complicated degrees of relationship – this is because they represent for a Wedda the real names for the person he has to deal with.

Apart from the features of name-giving described above, the ancient chronicles offer another difficulty, namely an indifference towards exact dating. In the documents, the historicity of events is always fixed by geographical, not by chronological orientation. The place where the king or fiefholder stayed and the local circumstances of previous or contemporary events play the preeminent role. Even recently, a priest could at once indicate the name and residence of the king under whose rule his dagoba had been built, when I asked him – but he could not give me any hint at the date.

This is why any exact chronological data are absent from the family tree of Taldéna Ménika. The only reference point is again Kumára Sínha holding court in Bádulla, on which event I currently don´t have any detailed information. The only possibility to approximately determine the date of the Sinhalese mixing with the old Wedda tribe is by counting the number of generations. According to the pedigree it dates back four generations. Mrs. Taldéna Ménika lived from 1869 till 1919. If we take 25 years for one Ceylonese generation, the racial mixing of Sinhalese and Wedda people may have started around the year 1769, that means, in the second half of the 18th century. The descendents of this family continue to live in Bádulla up till now.

It is evident that these old families whose members had been Dissáwas (Province chiefs) and Rátemahátmayas (District chiefs), are deeply rooted in the land. Due to the excellent intellectual and human qualities by which a great deal of the family members are excelling, due also to their love of the country, their impartiality and loyalty to their duty they are, even in our times, valuable administration bodies of the British government. A letter of a high British officer, dated March 4th 1913 and addressed to the Rátemahátmaya William R. Bibile can serve as

11 Good photo in C.and B. Seligmann: The Weddas, Cambridgen1911, Table VII

12 Good photos of him found in Seligmann, op.cit., Table V-VI

interesting evidence, because it acknowledges and at the same time admires “the strong feudal ties” that connect this family to the land.

In this connection I might also touch upon an important and for the Bibile family fatal event because it is related to the problem of the cultural-biological position of the Wedda – the Kandyan Rebellion on which unfortunately an in depth historical study is lacking up till now. It started in 1817 in the Uva province which until the beginning of British rule of 1815 had not yet experienced any domination by foreigners, and was organized by the Dissáwa of Badúlla. The execution of the British resident by arrows of Wedda troups at the road from Badúlla to Bibile – nowadays there is a memorial on the spot – was the signal for a general uprising. At this occasion the Wedda had been – and for the last time at that! – auxiliary troops of the Kandyans. According to a popular tradition, about which for understandable reasons the world will never get correct details any more, the young Rátemahátmaya Hinbanda of Bibile with his Weddas is said to have played a leading role at the execution. Long after the uprising had been oppressed in the Northern old Kandyan mountain districts, the fights continued in Uva, roughly until about 1822. The province was completely devastated. The Bibile family finally flew to the wild mountaineous region of the Eastern inner jungles where the Weddas of the old Moráne clan – relatives of them, as tradition has it -dwelled on the Danigála rock. The family was forced to purchase its return at the price of about 4/5th of its extensive landed property.

Additional data for the racial history of the Bibile family and its relation to the Wedda is made available by the current anthropological material, offered on the one hand by the family itself, and on the other by the last existing group of their traditional ancestors, the last Weddas of the old princely clan of the Moráne, settling in the Danigála mountains.

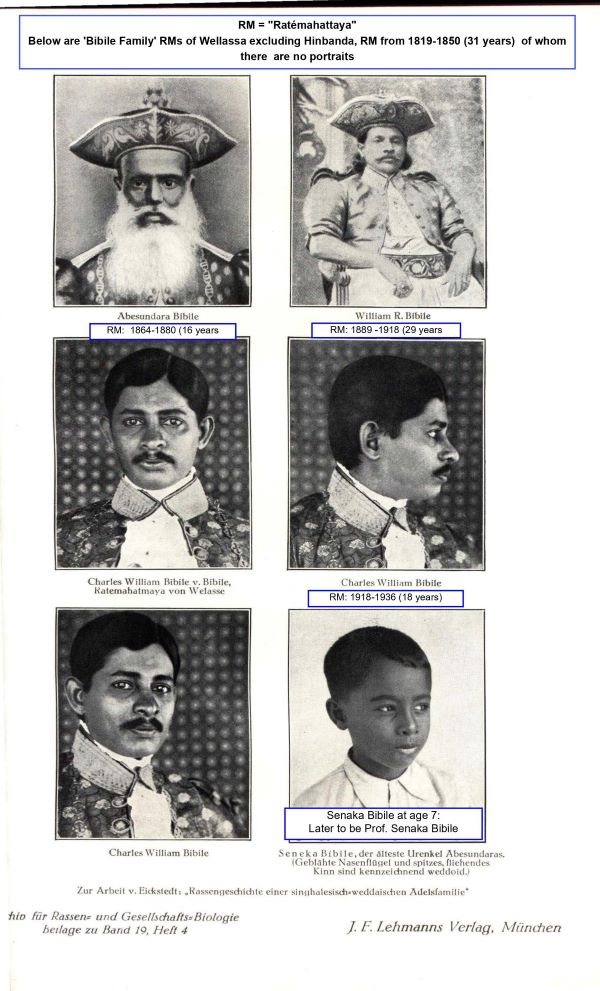

The p h o t o s from table 1 show the grandfather and the father of the current Rátemahátmaya, as well as himself and his son. The description of the grandfather, given by the anthropologist Emil S c h m i d t from Leipzig who must have been in Bibile about the beginning of August 1889, is quite accurate. S c h m i d t says:” After a long time came….the father of the Rátemahátmaya, in European dress, a beautiful Sinhalese head with a high forehead and long

rolling white beard.”13

Indeed, Abesúndare Bibile had been the characteristic anthropological

typus of a distinguished Kandyan, the north indian blood of his father Hinbánda absolutely dominating and the old Wedda blood of his mother Loku Ménika absolutely not recognizable any more. Completely different it is with his son, although his mother is the last representative of

13 E. S c h m i d t: Ceylon. Berlin 1897, p. 72.

an old purely Kandyan noble family full of rich traditions.14 E. S c h m i d tdid this already notice, too; he describes the then Rátemahátmaya as follows:” He was yet a young man, Sinhalese, but with his long, straight, pitch black hair, parted in the middle and combed back, with his hard featured, bony face, the dark piercing eyes, strongly protruding aquiline nose he reminded me more of a Red Indian than of a native of Ceylon…. His movements and manners were polished in a European way.”15

Indeed, on the group photos preserved by the family, the old Rátemahátmaya´s looks differ from those of the average type of the Kandyan nobility. His nose is rather high, as is typical for the “Aryan” (better to be called north indid from the racial point of view) inhabitants of Ceylon. But at the same time it shows a considerable width at the nostrils. Wide, distended nostrils, however, are one of the best marks of the Weddas, as also the protruding cheekbones that might in a large face look “bony and Red Indian”. By chance I found a passage in L e w i s16

with a quite similar description of a guaranteed mixed Wedda breed: “ The general cast of features is reminiscent of the North American Indian, in that the nose and cheek bones are strongly pronounced.” Examples of Weddoid formes of noses see on tables 2,6 and 7. The wide distended nostrils seem to be a highly characteristic feature of Weddas and Wedda mixed people, they also reappear in his son, the current Rátemahátmayam in a very expressive way (see table 1).

14 Bibile Waláue ( Waláue = seat of Nobles) preserves documents and silver swords, presented to this family by Sinhalese kings.

15 E. S c h m i d t, op. cit.,p. 39

16 F. Lewis, op. cit., p. 287

END