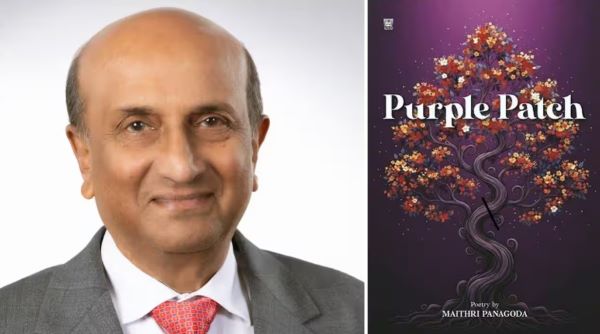

Perceptions of corruption in both developed and developing nations: a comparative analysis – By Dr Harold Gunatillake

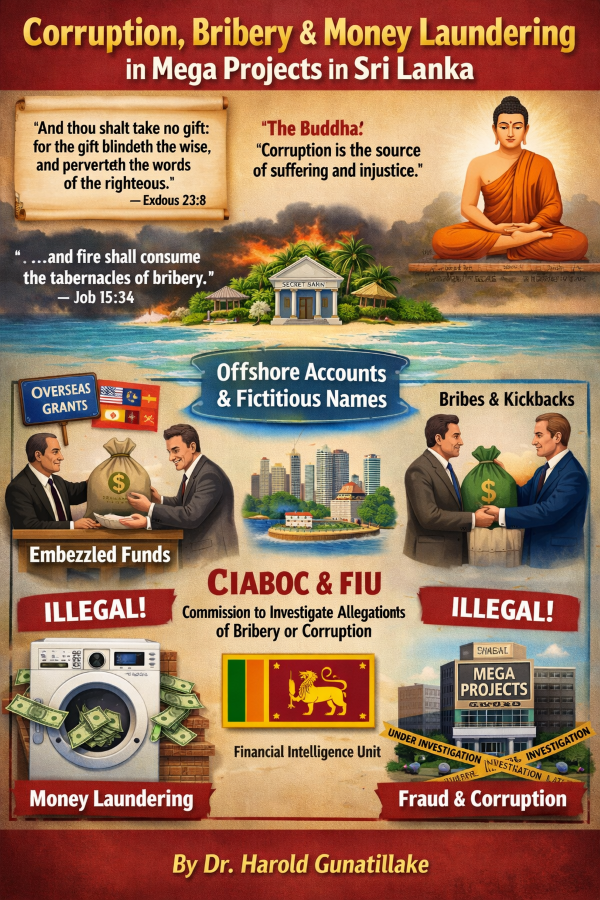

The Bible explicitly condemns the immoral act of bribery. God commanded Israel: “And thou shalt take no gift: for the gift blindeth the wise, and perverteth the words of the righteous.” (Exodus 23:8). In the book of Job, it is written: “… and fire shall consume the tabernacles of bribery” (Job 15:34).

The Buddha firmly denounced bribery and corruption, considering them as expressions of greed, dishonesty, and injustice that result in suffering and the deterioration of social trust. He engaged with this issue explicitly in numerous discourses within the Tipiṭaka.

The perception and impact of corruption vary significantly between developed nations such as the United States and numerous developing countries, particularly in Asia. In the United States, corruption is often institutionalised and manifests through complex channels, including lobbying, campaign financing, and regulatory capture. These practices, although sometimes legal or semi-legal, can lead to policies that disproportionately benefit affluent corporations or interest groups at the expense of the general populace. As a result, the consequences of corruption may seem abstract or indirect to many Americans. For instance, when large corporations influence legislators to shape regulations in their favour, it can result in increased costs for essential services, inadequate funding for public education, and deteriorating infrastructure. However, since these impacts develop gradually and are frequently obscured by bureaucratic procedures, they may not be perceived as immediate concerns in the daily lives of most citizens.

In various Asian nations and other developing regions, corruption often manifests in more immediate and tangible forms. Bribery and extortion present daily challenges for ordinary individuals seeking access to healthcare, education, or government services. In such contexts, corruption exacerbates existing poverty and inequality, as the most disadvantaged citizens are frequently the least able to afford bribes or navigate corrupt systems. The conspicuous nature of such corruption renders its impact unmistakable and typically incites widespread public frustration and protests. For instance, a family might be denied basic medical treatment unless they pay an unofficial fee, or a student may be compelled to pay bribes to participate in examinations or to receive grades, thereby directly hampering opportunities for social mobility and economic progress.

Despite these differences in visibility and immediacy, large-scale corruption in the United States continues to have substantial repercussions. Billions of dollars in public funds may be siphoned off or misallocated due to undue influence exerted by special interests, thereby diminishing the quality and accessibility of essential services. Although an American citizen may not be solicited for a bribe at the local council office, they may nonetheless encounter declining public transportation, escalating university tuition, or inadequate healthcare, all of which can be partially attributed to subtle, systemic forms of corruption that influence policy formulation. In both contexts, corruption diminishes public trust and undermines the social contract.

Nevertheless, the manner in which corruption is experienced and addressed varies according to societal structures, legal frameworks, and the visibility of its consequences.

Understanding these distinctions is crucial for developing effective anti-corruption strategies. In countries where corruption is overt and personal, reforms may focus on increasing transparency, simplifying bureaucratic processes, and empowering citizens to report abuses. In the U.S., however, combating corruption may require greater scrutiny of political donations, the closure of loopholes in lobbying, and greater accountability from public officials. Ultimately, while the form of bribery varies across countries, its capacity to distort societies and disadvantage the vulnerable remains a universal challenge.

The scenario delineated in a particular issue, such as corruption, bribery, and money laundering, is alleged to be widespread in large-scale projects within Sri Lanka. In these cases, officials frequently divert funds, including commissions derived from overseas grants, into foreign bank accounts and occasionally register fictitious names. Such practices are unlawful under Sri Lankan legislation, notably the Bribery Act and the Banking Act. Organisations such as the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC) and the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) are actively involved in initiatives to combat these illicit activities.

By Dr. Harold Gunatillake

End