Portugal and Sri Lanka: The Historiography Today

Source:Thuppahis

Chandra R. de Silva,* whose original title runs thus: “Portugal and Sri Lanka: Recent Trends in Historiography”[1] … an article that was originally published in Re-exploring the Links: History and Constructed Histories between Portugal and Sri Lanka, ed. Jorge Flores, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2007, pp. 3-26

In a recent article entitled ‘Theoretical Approaches to Sri Lankan History and the Early Portuguese period,’ Alan Strathern points out that although historical writing in Sri Lanka has become ‘the site of vibrant controversy’ due partly to the ethnic conflict, by and large, it has contributed little to wider debates on post-colonialism and the nature of historical thinking.’[2] I would agree with this broad proposition. What I intend to do in this paper is to extend my gaze beyond the sixteenth century to which Alan consciously limits himself and look critically at the extent to which historical writing in the past half century has enhanced our understanding of the complex connections between Portugal and Sri Lanka in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, … I will concentrate largely on the area of social interaction and leave the other areas — political, economic and cultural – for detailed consideration at a later time.

Sources Old and New

By the 1950s, most of the sources relating to the Portugal-Sri Lanka interaction had already been found and many of them had been published. Historians had used the work of the Portuguese chroniclers for many years.[3] Sri Lankan historians like S. G. Perera, Paul E. Pieris and Donald Ferguson had used unpublished Portuguese documents and had translated many of them into English.[4] The Portuguese Land Register (tombo) of 1614 was used as a source and some information from it was published.[5] The Tombo of the Two Korales completed by Miguel Pinheiro Ravasco was published in English translation in 1938.[6]A summary of the 1645 Portuguese revenue register of Jaffna was also in print.[7] In respect of indigenous sources, the Culavamsa and the Rajavaliya had been pub1ished.[8] So had the Yalpana Vaipava Malai.[9] Several of the war poems (hatan kavya) were in print and a number of Sinhala grants (sannas) had been examined.[10]

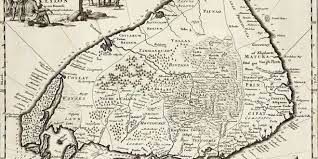

In comparison to what was known by the 1950s, few new primary sources were discovered in the last half-century. Perhaps most important among them was the Portuguese revenue register of Kotte, 1599 compiled by Jorge Frolim de Almeida, the first Portuguese superintendent of revenue in Sri Lanka. This document, published in English translation in 1975, gives important information on economic conditions in the southeast of Sri Lanka at the end of the sixteenth century.[11] A second was perhaps the publication by Tikiri Abeyasinghe in both Portuguese and in English translation of three seventeenth century Portuguese royal orders (regimentos) found in the National Archives in Goa’.[12] These, together with his summary of the material on Sri Lanka found in Goa, brought in a wealth of new evidence on the Sri Lanka- Portugal interaction. The final significant discovery was two sets of maps and plans of Sri Lanka published recently by Jorge Flores.[13] One of them – a set of maps and plans ordered to be compiled by Constantino de Sá de Noronha and completed in 1624 – was not totally unfamiliar because versions of it had been published twice, once from a copy in Washington’[14] and also from another version that had fallen into the hands of the Dutch).[15] The second set of maps completed in 1638 was more significant because it included plans of Kandy and a sketch of Adam’s Peak/Samanala Kanda. It also contained a description of Ceylon by the author of the sketches, Constantino de Sá de Miranda. As Flores points out, Miranda’s manuscript was copied by Fernão de Queyroz and forms the basis of much of Queyroz’s account of social structure among the Sinhalas.

Apart from these major finds, historians found hundreds of other documents that helped confirm, modify or contradict the specific incidents in the accounts that had been written up to the mid-twentieth century. Some of these documents appear in Fr. Vito Perniola’ s excellent three-volume collection, The Catholic Church in Sri Lanka: (The Portuguese Period).[16] Other significant documents relating to the Sri Lanka- Portugal interaction appeared in collections of Portuguese documents.[17] The publication of Paulo da Trinidade’s Conquista Espiritual do Oriente, written in the 1630s[18] and used as a source by Fernão de Queyroz[19] provided a new resource for the study of religious interactions and the translation into English of the sections relating to Sri Lanka made it more accessible.[20]

In the case of Sinhala and Tamil documents there were no major new finds,[21] although the Matatakkalappu Manmiyam (The Glory of Batticaloa) edited by F. X. C Nadarajah[22] has some interesting references to Portuguese relations with Batticaloa and Kandy in the seventeenth century. Some war poems that had been known in manuscript form such as the Sitawaka Hatana were edited and published[23] as was the Alakesvarayuddhaya,[24] a sixteenth century Sinhala account that was a source of the better known Rajavaliya.

Contextual Perspectives

For much of the last half century, historical investigations on the interactions between Portugal and Sri Lanka have been left largely to Sri Lankan historians.[25] These historians, living in an era that had just seen the end of British colonial rule in Sri Lanka, had as a major objective the writing of a new history of Sri Lanka, free from imperialist distortions, yet based on available evidence. A major problem was that, due to the paucity of indigenous records, the sources of information were in Portuguese or other European languages. These professional historians did not see the impact of Portugal on Sri Lanka merely as an example of colonial aggression or merely as an episode in the modernization process. Instead, by reading these documents and carefully interrogating them, they sought to build a detailed picture of how the Portuguese became involved in Sri Lanka, how they had an impact on the institutions and the lives of the people and how the Portuguese themselves were impacted by the interaction. Although they differed in their perspectives, together, they produced an extensive collection of studies that dealt with matters ranging from war and political conflict to agriculture and land tenure as well as religious conversion and social change.

Professional Sri Lankan historians, on the other hand, have stayed away from wider theoretical debates about the nature of colonialism, theories of resistance, identity formation, subaltern studies and the like. One can only speculate as to whether this was due to the training in ‘positivist’ history that many of these scholars gained in England or whether it was a function of their own individual approaches. It is, however, true that some of these newer approaches came to have an impact on academic writing only in the 1960s and 1970s and that contemporary Indian scholars writing on Portuguese contacts were not much better at engaging them (until the advent of Sanjay Subrabmanyam). Moreover, these Sri Lankan historians saw their task principally as the rewriting of the history of their country and if there was a contribution through that to a wider reconsideration of the nature of their discipline, that was a secondary concern. It is only more recently that scholars of Sri Lankan origin, writing from abroad, have widened their approach to engage current theoretical debates.[26]

Portuguese scholars, with few exceptions had tended to ignore the Sri Lanka-Portugal interaction for much of the mid twentieth century and this was not surprising given the debates in Portugal up to the 1970s about the then existing imperial possessions in Africa, Goa and Timor. However, Genevieve Bouchon, a recognized French scholar, made up for this with some interesting pieces of investigative historical writing.[27] Once interest revived in the 1990s, there was a tendency among Portuguese writers to frame the Portugal-Sri Lanka interaction in a wider context. This explains, at least in part the conception of ‘the Sea of Ceylon’ propounded by Jorge Flores.[28] Other European and American scholars working on the interaction recently – Alan Strathern, Zoltán Biedermann, Kenneth Jackson, and George Souza – are also clearly engaged in wider historical debates.

In contrast, works emanating from Sri Lanka recently have taken continued to be very narrowly focused, with great efforts expended on determining the exact name of a particular ruler or the exact place the first contact occurred.[29] It is not that these matters are unimportant[30] and indeed I have an appendix to this paper dealing with some recent debates on such matters (See Appendix 1) but it is not all that matters and Sri Lankan historians need to engage in wider historical debates if they are to better understand their own objectives.

Social Interactions

Religion has been a key ingredient in the analysis of the Sri Lanka- Portugal encounter. The matter is complicated because the evidence from both sides has often depicted the encounter as leading to a religious conflict. For instance the Yalpana Vaipava Malai commenting on the events in Mannar in the 1540s states “It was a sworn duty among the Portuguese to try to spread their religion wherever they went. Owing to the force of their preaching, a number of families embraced Catholicism[31] at Mannar. As soon as Sankili heard of this conversion, he put six hundred persons to the sword without any distinction of age or sex.” [32] The Portuguese records are also very clear on the religious divide. Here is an account of the events of the Portuguese expedition of 1560 as related from Mannar on 8 January 1561 by Anrique Anriques[33] to J. Lainez, superior-general of the Jesuits in Rome.[34]

“One article of the treaty stated that no impediment would be placed in the way of those who wished to be baptized, and that those who received baptism would pass under our jurisdiction, though they would be obliged to pay the royal taxes. The people began to be baptized. The bishop of Cochin, a very virtuous prelate, administered baptism to the people of a village on the coast. He baptized four hundred or more persons. Father Misquita and I were with the viceroy. We baptized some leading persons of some villages, together with their kinsmen, about one hundred and twenty in all. It was hoped that before long all the inhabitants of the island would become Christians. In the meantime the king was paying the money he had promised.

Then all of a sudden the whole country rose against us. They killed the custodian of the Franciscans and some Portuguese who were going with him to destroy a temple, which, however, was not destroyed at that time, as the people were ready to start a war.”

The Sinhala Rajavaliya also emphasizes the conflictual aspect of the religious interaction: “Bhuvanekabahu, who lived in intimacy with the Portuguese committing foolish acts, was killed by them as a consequence [owing to the karma] of his foolish act in entrusting to the Portuguese king the prince he had brought up [his grandson]. It should be known that Bhuvanekabahu brought misfortune on future generations in Sri Lanka and that, owing to him, in later times harm befell Buddhism (Buddha Sasana).”[35] Many popular Buddhist writings in Sri Lanka place emphasis on this theme. There is little doubt that the Portuguese missionaries who arrived in Sri Lanka generally regarded both Buddhism and Hinduism as ‘superstitions’ and tried to destroy them.

However, as K. W. Goonewardena pointed out in the l950s[36] and as Alan Strathern has conjectured more recently,[37] Bhuvanekabahu of Kotte might have offered to patronize the Christian missionaries because he viewed attending to all the religious needs of his subjects as-the function of a ruler. This brings up a picture of Sri Lankan Buddhism[38] and Hinduism of the time as being very tolerant of different faiths. This seems to be borne out by the absence of hostility to the monotheistic Muslims in the period before the arrival of the Portuguese. On the other hand, there is some evidence that some boundaries were drawn in debates on the acceptance of new rituals, practices and ideas.[39] There is plenty of evidence of religious persecution by the Portuguese and attacks on churches during war by both Buddhists and Hindus.[40] Some of us have argued that Buddhism (and Hinduism) might have become more explicitly defined and become less tolerant due to the interaction with missionary Christianity.[41] Others have argued that Buddhists remained tolerant and accepting even at the end of Portuguese colonial rule in Sri Lanka.[42] The first contention was partly based on the Mandarampura Puvatha. With Malalgoda’s convincing essay depicting the Mandarampura Puvatha as a forgery,[43] and British accounts of the tolerant attitude of Buddhist monks in the early nineteenth century, it might be time to return to the question: What evidence do we have of changes in indigenous religions due to a clash with a new exclusivist doctrine[44] and how does this evidence relate to other encounters in other parts of the world? What did being a Buddhist or a Saivite Hindu imply in the sixteenth or seventeenth century in terms of beliefs and lifestyle? The question is not only whether we agree with Carter that the notion of ‘religion’ among Buddhists changed with the arrival of Christianity or with Malalgoda that a notion of religious ideology exited long before[45] but also whether the Portuguese impact differentially affected elements within Buddhist and Saivite beliefs.[46]

Religion has also had its impact on the evaluation of the Portuguese impact on Sri Lanka. As I have pointed out in an earlier publication Christian converts have had a much more sympathetic view of Portuguese influence than Buddhist (or indeed Hindu and Muslim) writers. That was the classic contrast between the Kustantinu Hutana, a poem written by a convert in praise of Constantino de Sá de Noronha and the other hatan kavyas that depict the Portuguese as destructive and cruel. This debate had been continued in the twentieth century between the Jesuit scholar Simon Gregory Perera and the nationalist Paul E. Pieris. By the mid-twentieth century, despite the popularity of Pieris’s Ceylon: The Portuguese Era, the adoption of S. G. Perera’s History of Ceylon as a school text had ensured that most Sri Lankans grew up with a more favorable view of the Portuguese impact than the nationalist popular legends suggested.[47] In the

1950s and 1960s Professor K. W. Goonewardena challenged some of the perspectives presented by S. G. Perera and although he did not publish many of his thoughts relating to the Portuguese,[48] the views that he imparted had an impact on a new generation of Sri Lankan scholars. Meanwhile, Charles Boxer challenged Perera’s view that conversions to Christianity were made without force. One of Goonewardena’s students, Tikiri Abeyasinghe after a dispassionate discussion of the issue concluded that while conversion might not have been made ‘at the point of the sword,’ force was indeed used against Buddhism and Hinduism.[49]

I have elaborated on this point in some detail because there continues to be a critical view of the Portuguese colonial connection in more popular Sinhala writings. A good example of this was politician Philip Gunawardane’s Sitawaka Urumaya that sought to depict the rulers of Sitawaka as national heroes resisting Portuguese incursions.[50] This tendency has been echoed more recently.[51] In times of tension between Buddhists and Christians in Sri Lanka, there has been a tendency to saddle local Christians with responsibility for the adverse effects that Portuguese colonialism had on Buddhism. In contrast, some Sri Lankan Christians have contended that both Buddhism and Christianity came to Sri Lanka from outside.[52]

This brings us to the related question of identity. John Rogers has argued that the predominant identity in pre-modern Sri Lanka was religious rather than caste or ethnic.[53] Alan Strathern has probed this question further by asking what it meant to be a Buddhist or a Saivite in the sixteenth century.[54] Was there a Buddhist ideology that deterred a ruler such as Bhuvanekabahu of Kotte (1521-1551) from converting to Christianity? If so, why were kings and princes such as Karaliyadde Bandara of Kandy (1552-1582) so ready to offer to convert?[55] Yet, if it were not important why did Vimaladharmasuriya reconvert to Buddhism in 1593 when he appears not have had strong loyalties to that religion?[56] What did the mass conversions in Kotte and Jaffna in the seventeenth century mean? How much of their former identity did the converts have to give up and what did they retain? Despite the imbalance of political power Christianization was clearly not just a process of ‘writing a distinct message into alien minds’ but one where Christianity ‘responded to new local traditions and social strategies.’[57] The founding of separate parish churches for different castes in Sri Lanka is a clear example of adaptation.

On the other hand, Michael Roberts in his recent work on Sinhala consciousness argues that Sinhala identity might have been forged during the long struggles against the colonizers.[58] Perhaps a re-reading of the hatan kavyas and other literature might be useful here. Finally, one must not ignore the question of caste identity. There is a great deal of evidence on caste in Sri Lanka in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that might be applied to the current debates on the ‘invention’ of caste.[59] Research in the last fifty years has also shown that caste identities in Sri Lanka were altered under pressure from colonial rule. People from the batgam and karava castes were made to peel cinnamon under Portuguese rule,[60] and K. W. Goonewardena has indicated that pannayas were peeling cinnamon in Wallallawiti Korale in the first half of the seventeenth century.[61] The reaction to Portuguese colonial rule might have been different according to caste identity. Portuguese rule eventually proved to be burdensome to the salagama caste, many of who had the obligation of cinnamon peeling. In contrast, some elements of the karava caste might have been relative beneficiaries.[62] It is possible that the Sinhala and Tamil identities were fractured in terms of caste and that Portuguese rule enabled some of the so-called ‘lower’ castes to escape the distinctions of dress that were traditionally imposed on them. As Queyroz points out” … among the Lascarins it is more common to wear very short breeches, and in this garb they think they can walk with dignity through the noblest quarters. Those who are able, wear a sheet wrapped round the waist which at night serves them as a coverlet.”[63] On the other hand, the Portuguese impact might have stimulated a process whereby in certain parts of Sri Lanka, marginal castes might have become more powerful and even hegemonic and thus begun to develop a challenge to the traditional caste based elite discourse.[64]

Questions of identity arise on the Portuguese side as well. Jorge Flores has illustrated how the ‘discovery’ of Sri Lanka helped King Manuel to enhance his reputation.[65] What we know less about is how the colonial enterprise in Sri Lanka affected Portuguese identity. People from many other areas in Europe participated in the Portuguese colonial enterprise. This was true in the missionary enterprise as well as in trade, though the Portuguese nationals manned much of the political structure. [66] We have some studies on how the empire impacted on Portugal. There is increasing recognition that, while travel and missionary literature did not lead to a good understanding of the ‘other,’ Portuguese ideas about Asians were impacted by this literature and evolved in time. I would like to see more on how the Sri Lankan enterprise in particular affected Portuguese self-definitions in various social strata.

It is also time to look beyond the Portugal – Sri Lanka dichotomy. Developments in this period involved multiple interactions and intersecting linkages. Both indigenous and European sources speak in multiple voices mediated by class, caste, and religion. Thus for example, a study of the Sinhala Christian literature might indicate not only what the European missionaries thought would be suitable reading but also give us some clues on the story of Sinhala and Tamil converts and their struggles for social standing.[67]

Political Structures

The Portuguese enterprise had an impact on the state in Portugal and on Portuguese political influence in Europe. Several historians have pointed out how King Manuel used ‘the discovery of Ceylon’ to enhance his prestige with the Papacy.[68] One cannot but notice the urge to document and map imperial possessions, an urge that seems to gather momentum in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Whether this was a product of Spanish influence on the Portuguese or was an independent development spurred by the need to control a growing empire that was increasingly being challenged is still to be determined. The ways in which profits from the Portuguese king’s commercial monopolies impacted on his power within Portugal is another area worthy of continued investigation.

The interaction also modified the political structures in Sri Lanka. The last fifty years have seen several scholarly examinations of political developments and administrative structures. Historians have pointed out that the state officials were more than a ‘mobilizing center’: they actually provided machinery for justice and revenue collection in areas outside the capital and the Portuguese, when they obtained control of territory adapted the existing systems to exert power.[69] In more recent times there has emerged some analyses of the nature of the Sri Lankan state in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Alan Strathern has convincingly argued that the glory of being ‘chakravarthi’ or Emperor [of Lanka] was not vitiated by paying tribute to an external power. Indeed, alliance with and protection from a powerful external might have enhanced the aura of the locally dominant ‘emperor.’ [70] This was also true within Sri Lanka where allegiance to and protection from the anointed ‘chakravarthi’, enhanced the prestige of sub-rulers.[71]

There has also been some scattered drawing from models of pre-colonial states to explain the Sri Lankan state system. Nevertheless, there has been some reluctance among Sri Lankan historians to adopt models such as Tambiah’s concept of a ‘galactic state’ for Sri Lanka. This is not because there is any doubt that the ruler’s power was stronger in the center than in the periphery, indeed, the model of the kingdom of Kotte indicates that the ruler’s claims became more shadowy in the outlying areas. Nevertheless, in Sri Lanka, as in the Maldives, the state seems to have a recognized optimal size and thus major conflicts seem to be geared as much towards possession of a ritual capital city that would facilitate legitimacy as the supreme ruler as much as gaining peripheral lands on the frontier.[72]

What is not very clear from research up to the present is the extent to which Portuguese intervention had an impact on the nature of the Sri Lankan state. The evidence is scanty and it is difficult to argue for the emergence of the ‘early modern state’ in Sri Lanka although Sitawaka’s swift incorporation of European firearms and Rajasinha’s naval ambitions as well as his efforts to control the supply (and thus the price) of cinnamon illustrate some interesting tendencies.[73] On the other hand, there is some evidence of the growth of a standing army with related pressures for a more efficient collection of revenue.

Economic Interaction

The development of the Portuguese colonial enterprise changed the Portuguese economy in many ways and Sri Lanka’s exports played some role in that. Sri Lanka’s role however, is difficult to disentangle from that of the rest of the Estado da India. It is easier to estimate the Portuguese impact on the Sri Lankan economy that has been dealt with in some detail in works published by Sri Lankan historians in the last half century.[74] There was clearly an increase in the production and export of cinnamon. Nevertheless, there has been little or no comment on the extent to which the Portuguese commercial enterprise was innovative. Steengaard’s contention that the Portuguese colonial enterprise was merely ‘redistributive’ in contrast to the ‘productivity enhancing’ activities of the Dutch and British companies has gone without comment from Sri Lankan historians though it has been challenged by others.[75] There has been no effort to use Sri Lankan data to challenge or confirm Michael Pearson’s contention that Asian rulers were not essentially concerned with participation in trade. There have been no sustained efforts to link the evidence of migrations from South India to Sri Lanka to the growth of commerce or politico-cultural changes.[76] For many of these questions there might not be enough data to give specific answers but new questions could enable us to glean more information from old sources.

Culture and the Arts

Finally, there is the area of culture and the arts. It is sometimes difficult to determine the exact provenance of some of the surviving cultural artifacts but there is enough evidence to argue that the arts (including music, furniture, jewelry and religious objects as well as architectural styles) might be one of the areas in which there have been some fruitful interchanges.[77] There is increasing recognition that church facades have influenced Buddhist temple architecture in the southwestern coastal belt of Sri Lanka. Because Portuguese Creoles and songs have received a great deal of attention in the last half-century,[78] the arts might be an area where one would see more productive writing in the years to come.

Concluding Remarks

The past half-century has seen some major advances in our knowledge of the interactions between Portugal and Sri Lanka. Even if there are few major discoveries of new source material, I am confident that the coming half century will see a fruitful reexamination of existing sources and new perspective on the relationship. The Quincentennial observances of the coming year are bound to stimulate scholarly interest on the subject. If all historians, both Sri Lankan and Portuguese continue to interrogate their sources and ask new questions from old materials, we could see some fascinating new approaches to an old relationship.

This Pix from http://muculmanoeportugues.blogspot.com/2019/04/o-ceilao-portugues.html

This Pix from http://muculmanoeportugues.blogspot.com/2019/04/o-ceilao-portugues.html

APPENDIX I

Disputed Chronology on the First Encounter: 1505, 1506 or 1501?

In a comprehensive essay written almost a hundred years ago, Donald Ferguson,[79]argued that the visit of Portuguese led by Dom Lourenço de Almeida could not have been in 1505 but in 1506. He pointed out that if the Portuguese had reached Sri Lanka in 1505, news of the discovery would have reached Portugal through letters on S. Gabriel that left India in February 1506 and reached Lisbon by late 1506 or early 1507. If so, it was difficult to explain why the King of Portugal waited till September 1507 to write to the Pope about this ‘discovery’, something that was perceived as so important that it was celebrated with a procession in Rome on December 21, l507.[80] Ferguson also pointed out that if the first contact had been in 1505, it raised the question as to why Viceroy Dom Francisco de Almeida did not mention it in his letter to King Manuel dated December 16, 1505.[81] In addition, he also pointed out that the instructions to the Portuguese Viceroy had specifically instructed him to begin voyages of discovery only after the ships had been loaded with return cargo to Portugal. This was not complete till early 1506. Furthermore, two of the envoys who were reported to have gone on embassy to the King of Kotte could not have done so in 1505 because one of them, Payo de Souza was still on his way to India and the other, Fernão Cotrim, was the factor at Kilwa in 1505.[82] Nevertheless, well into the mid-twentieth century, 1505 remained the accepted date for the first encounter among both historians and the general public in Sri Lanka and Portugal.

This was largely on the strength of the account of Fernão de Queyroz that stated that the first encounter was in l505.[83] Queyroz’s work, first published in Portuguese in 1914 and available in an excellent English translation in 1930 was accepted as the most authoritative Portuguese account of the relations between Sri Lanka and Portugal in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Queyroz himself wrote in the 1680s. However, he might have derived his information from the work of Diogo do Couto who began writing in the 1590s. Both of them might have relied on the assertion of Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, who wrote in the 1540s, that the first visit came in 1505.[84] On the other hand, Gaspar Correia, the only chronicler whose work suggested that the Portuguese might have arrived in 1506, was deemed by Ferguson himself to be “generally untrustworthy.” C. R. de Silva in a brief article published in 1978, brought the Ferguson date (1506) back into the debate.[85] What he did was to point to a near contemporary source that identified the date of the arrival of the Portuguese in Sri Lanka. The source was a pamphlet in Spanish by Juan Augur originally published in Spanish in Salamanca in 1512. The information in the pamphlet was based on a first hand account of events in the East given by Martin Fernandes de Figueroa. The account mentions the activities of Dom Lourenço de Almeida till March 1506 and continues as follows: “. . and the winter over, on the 8th day of August, Dom Lourenço; son of the Viceroy left at the head of seven ships to discover the islands athwart Cochin and with strong storms and contrary winds went to cast anchor in Ceylon, the island of cinnamon.”[86] Since that time, the date of 1506 is generally adopted as a possible alternative[87] and is increasingly being accepted among historians today although 1505 continues to have life among more popular historical narratives.

In 1980, Genevieve Bouchon, having examined a Portuguese stone inscription in Colombo that seemed to have the 1501 inscribed on it, advanced the hypothesis that the first encounter might have occurred well before de Almeida’s visit, by a vessel from the first fleet of João da Nova to arrive in the Indian Ocean.[88] This idea has found virtually no support. Some have suggested that the inscription should be read not a 1501 but JSOI meaning Jesus Salvator Orientalium Indiorum or Jesus, Savior of the East Indies.[89] Jorge Flores, has pointed out that the 1501 thesis is not supported by the evidence because the ‘discovery’ of Sri Lanka is not mentioned in a contemporary account of João da Nova’s expedition. Neither is there evidence for ‘discovery ‘in any of the documents that relate to the period 1501-1505. Indeed, Flores legitimately raises the question on why King Manuel gave instructions in 1505 to Dom Francisco de Almeida to ‘discover’ Ceylon if João da Nova’s ships had already found the island.[90]

Ruler of Kotte at the Time of the First Encounter: Vira Parakramabahu or Dharma Parakramabahu?

The identity of the ruler in power in Kotte at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese has been a matter of dispute. Fifty years ago, the accepted theory propounded by historians S G. Perera and H. W. Codrington was that at the turn of the sixteenth century the ruler of Kotte was Vira Parakramahahu VIII.[91] In 1961, Senerat Paranavitana using evidence from the Sinhala chronicle, the Rajavaliya,[92] a reinterpretation of a Sinhala inscription (the Kelani Vihara Inscription, of 1509), and evidence from Portuguese sources made a strong argument that the ruler was Dharma Parakramabahu IX and fixed his reign as 1491-15l3.[93] G. P.V. Somaratne in his 1975 monograph accepted this conclusion though he concluded that Dharma Parakramabahu IX ruled from 1489 to 1513.[94] Most scholars have accepted this theory.[95]

In 1971, Genevieve Bouchon challenged this chronology and revived the theory that the ruler of Kotte during first contact was Vira Parakramabahu VIII.[96] Bouchon pointed out that Dharma Parakramabahu was not mentioned either in the Culavamsa or in the Rajaratnakaraya and that the Parakramabahu in the Kelani Vihara Inscription could have been either ruler. Pointing out that evidence from the Veragama Sannasa, tbe Kadirana Sannasa and the inscription at Kappagoda indicate that Vijayabahu claimed to be ruler of Kotte from 1509, she claims that there was no ruler called Dharma Parakramabahu and that Vira Parakramabahu was succeeded by Vijayabahu (1509-1521). In support of this idea she points out that on November 30, 1513, Viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque wrote to his king, D. Manuel as follows: “…the king of Ceilam is dead; he has two Sons and there is division between them over the succession to the throne.”[97] According to the Rajavaliya, Dharma Parakramabahu had no sons. Vira Parakrarmabahu did. Therefore, Bouchon concludes that Vijayabahu might have claimed the throne from 1509 (Portuguese sources report the ruler as old and sick in 1508) but that Vira Parakramabahu (1489-1513) actually reigned till his death in 1513 and was succeeded by Vijayabahu (1509-1521).

More than twenty years later, Mendis Rohanadheera, in several publications, has repeated this assertion.[98] Rohanadheera’s arguments reflect Bouchon’s contentions though he does not cite her work and might not have been aware of it.[99] He adds a new dating of the Gadaladeniya inscription which he now ascribes to Vira Parakramabahu[100] and then goes on to claim that Dharma Parakramabahu was not a ruler, but a pretender who deceived the Portuguese into thinking that he was king. In fact, the English translation of his 1997 booklet reads Dharma Parakramabahu: The Fake King of Ceylon invented by the Portuguese! He (like Bouchon) claims that the Rajavaliya, a chronicle that clearly identifies Dharma Parakramabahu as the ruler when the Portuguese arrived, was composed in the late seventeenth century. Indeed, Rohanadheera goes further by suggesting that the Rajavaliya was contaminated by ‘fake’ Portuguese data.

However, we know that the Rajavaliya was based on earlier accounts including the Alakesvarayuddhaya.[101] I have argued elsewhere that the Alakesvarayuddhaya was probably composed in the late sixteenth century and that, in both these Sinhala chronicles, internal evidence suggests that the recounting of the events might have come from an earlier source that might be dated as early as the mid-sixteenth century.[102] It is also clear that it was the Portuguese chroniclers who gleaned information from the Sinhala chronicles rather than the other way round although information must have flowed both ways. In any case, it seems clear that both Bouchon and Rohanadheera are incorrect in assuming that the relevant sections of the Rajavaliya were composed in the late seventeenth century.[103] It is more likely that they date from the mid-sixteenth century and are therefore more credible. Finally, there is the additional evidence in the Sitawaka Hatana which identifies the ruler at the time as Dharma Parakramabahu.[104] The major argument against Dharma Parakramabahu being ruler from 1489 to 1513 thus appears to be Albuquerque’s letter of 1513 quoted above. However, we know that the Portuguese rule of succession was through sons and the Kotte practice was for brothers to succeed. It is possible that Albuquerque or his informant mistook the heirs who were brothers to be sons.[105] This could have been an understandable error in transmission of information. Therefore, the evidence still seems to point to Dharma Parakramabahu (r. 1489-1513) as the ruler during first contact.

The First Encounter: Where?

Half a century ago, the major textbook in Sri Lanka’s schools, S. G. Perera’s History of Ceylon: The Portuguese Period, 1505-1658, clearly stated that the Portuguese first arrived in Sri Lanka at the port of Galle but then sailed up the coast to Colombo where they negotiated with the ruler of Kotte.[106] Here, Perera was following the account of Fernão de Queyroz, the Portuguese historian of the late seventeenth century. However, the earliest historian to write on the first encounter, João de Barros, who wrote in the 1520s simply stated that the Portuguese visited the port of Galle and negotiated with the ruler there.[107] Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, also writing in the mid-sixteenth century claimed that the Portuguese arrived in Galle.[108] The earliest Portuguese commentator to state that they arrived in Colombo was Gaspar Correia[109] but most historians have regarded him as somewhat unreliable. Diogo do Couto asserts that the Portuguese came to Colombo[110] but he wrote at the end of the sixteenth century.

Mendis Rohanadheera, marshalling all this evidence in 1999, argued that the Portuguese actually came to Galle and negotiated with and were deceived by some Muslim merchants who pretended to take them to the local ruler.[111] It is indeed possible that the Portuguese first arrived in Galle but the problem with the assertion that they negotiated with a local ruler in the south is that the Alakesvarayuddhya and Rajavaliya contradict this. There is reason to think that the Sinhala descriptions of the events of 1506 were composed in the mid-century, if not earlier. If so, the Sinhala account was written in Sri Lanka to be read by persons who were a few decades removed from the events. Barros, on the other hand, though he wrote in 1524, never visited the East and Castanheda could well have read Barros’ account.

The First Encounter: Exchange of Gifts or Treaty

Half a century ago, it was accepted that the first contact led to a treaty in which the ruler of Kotte promised tribute and vassalage to the Portuguese.’[112]However, subsequent Sri Lankan historians have cast doubts on this story.[113] They pointed out that while Casianheda, Couto and Queyroz all maintain that there was a treaty, and while there was some evidence that the Portuguese ruler might have believed that as well, other sources such as the Rajavaliya and Gaspar Correa’s account claim that all that happened was an exchange of presents. Both Barros and Castanheda also maintain that the Portuguese did not deal with the ruler of Kotte but with either Muslim merchants or a ruler of Galle. Castanheda admits that the Portuguese did not receive any tribute payments after 1506 and it is clear that when they returned in force in 1518 with a much larger fleet all that the Portuguese asked for was simply permission to build a fort. Jorge Flores points out that the discovery and ‘conquest of Taprobane (Sri Lanka) was seen a significant achievement that brought great prestige to the Portuguese king.’[114] The amount of ‘tribute’ promised seems to grow as Portuguese further and further removed from the events began to retell the story. For all these reasons, most historians currently discount the story of a promise of ‘tribute’ in 1506. It is likely that whatever occurred might have been seen by the Sri Lankan ruler as an exchange of presents or even as the gracious reception of foreigners bearing gifts on the model of the Chinese system. On the other hand, it is almost certain that the local ruler was aware of Portuguese sea-power. As Zoltán Biedermann points out, the concept of chakravarthi or supreme ruler in Sri Lanka has traditionally been reconciled with payment of tribute to an external power and therefore it is not inconceivable that the ruler of Kotte could have agreed to payment in return for patronage and military assistance.[115]

**** ****

Chandra R de Silva taught History at Peradeniya University and was a key figure in the Ceylon Studies Seminar. After migrating to USA, he rose to high office in Old Dominion University.

Chandra R de Silva taught History at Peradeniya University and was a key figure in the Ceylon Studies Seminar. After migrating to USA, he rose to high office in Old Dominion University.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abeyasinghe, T. “History as Polemics and Propaganda: An Examination of Fernão de Queiros History of Ceylon”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Sri Lanka Branch, new series, XXV (1980-81), pp. 28-69.

Abeyasinghe, T. “The myth of the Malvana Convention”, The Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, new series, XVII (1973), pp. 11-21.

Abeyasinghe, T. “Portuguese Rule in Kotte, 1594-1638”, in K. M. de Silva, ed., University of Peradeniya, History of Sri Lanka, vol. II, (Peradeniya, 1995).

Abeyasinghe, T. Portuguese Rule in Ceylon 1594-1612, (Colombo, 1966).

As Gavetas do Torre do Tombo, 10 vols. (Lisbon, 1960-1974).

Alakesvarayuddhaya, ed. A. V. Suraweera (Colombo, 1965).

Alden, Dauril The Making of an Enterprise: The Society of Jesus in Portugal. Its Empire and Beyond, 1540-1750 (Stanford, 1996).

Alguns Documentos da Torre do Tombo acerca das navegações e conquistas portuguezas, ed. Ramos Coelho (Lisbon, 1892)

Amerasingha, Risiman Aithihasika Sitawaka (Colombo, 1990).

Amerasingha, Risiman Sitawaka Rajadhaniye Unnathiyeda Avanathiyeda Samahara Ansha Pilibanda Vimarshanayak (Colombo, 1998).

Asgiri Talpatha, Mendis Rohanadheera, ed. (Colombo, 1997).

Biedermann, Zoltán “Tribute, Vassalage and Warfare in Early Luso-Lankan Relations (1506-1543)”, in Fatima Gracias, Celsa Pinto and Charles Borges, eds., Indo-Portuguese History: Global Trends. Proceedings of the XIth International Seminar on Indo-Portuguese History (Goa, 2005), pp. 185-206.

Bouchon, Geneviève “A propos de l‘Inscription de Colombo (1501). Quelques observations sur le premier voyage de João de Nova dans l’Océan Indien”, Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, XXVIII (1980), pp. 235-270.

Bouchon, Geneviève “Les Rois de Kotte au début du XVIe siècle”, Mare Luso-Indicum, 1 (1971), pp. 65-96.

Bugge Henriette and Rubiés, Joan Pau eds., Shifting Cultures: Interaction and Discourse in the Expansion of Europe (Munster, 1995)

Cartas de Afonso de Albuquerque, seguidas de documentos que as elucidam, ed. R. A. de Bulhão Pato, vol. 1 (Lisbon, 1884)

Carter, John Ross “The Origin and Development of ‘Buddhism’ and ‘Religion’ in the study of Theravada Buddhist Tradition”, in On Understanding Buddhists: Essays on the Theravada Tradition in Sri Lanka (Albany, 1993), pp. 9-25.

Codrington, H. W. A Short History of Ceylon (London, 1947).

Constantino de Sa’s Maps and Plans of Ceylon, l624-1628, ed. E. Reimers (Colombo, 1929).

Correa, Gaspar, Lendas da India, 4 vols. (Lisbon, 1858-1866)

Culavamsa being the more recent part of the Mahavamsa, W. Geiger, trans., (London, 1930).

da Silva Cosme, O. M. Fidalgoes in the Kingdom of Kotte, Sri Lanka 1505-1656 (Colombo, 1990).

da Trindade, Paulo Chapters on the Introduction of Christianity to Ceylon taken from the Conquista Espiritual do Oriente of Friar Paulo do Trindade, trans. Edmund Pieris and Achilles Meersman (Colombo, 1972).

da Trindade, Paulo Conquista Espiritual do Oriente, 3 vols. (Lisbon, 1960-1967).

de Castanheda, Fernão Lopes, História do Descobrimento e Conquista da India pelos Portugueses, 9 vols. (Coimbra 1924-1933).

de Silva, C. R. “Algumas reflexões sobre o impacto português na religião entre os Singaleses durante os séculos XVI e XVII”, Oceanos, 34 (1998), pp. 104-116.

de Silva, C. R. “Beyond the Cape: The Portuguese Encounter with the Peoples of South Asia”, Implicit Understandings: Observing. Reporting, and Reflecting on the Encounters between Europeans and Other Peoples in the Early Modem Era, Stuart B. Schwartz, ed.,(Cambridge, 1994), pp. 295-322.

de Silva, C. R. “Portuguese Interactions with Sri Lanka and the Maldives in the Sixteenth Century: Some Parallels and Divergences”, Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities, XXVII & XXVIII (2001-2002), pp. 1-23;

de Silva, C. R. “The First Visit of the Portuguese to Ceylon 1505 or 1506?”, in Indrapala Prematilleke and Lohuizen van Leeuw, eds., Senerath Paranavithana Commemoration Volume (Leiden, 1978), pp. 218-220.

de Silva, C. R. “The Kingdom of Kotte and its Relations with the Portuguese in the Early Sixteenth Century”, in E. C. T. Candappa and M. S. S. Fernandopulle, eds., Don Peter Felicitation Volume (Colombo, 1983), pp. 41-42.

de Silva, C. R. “The Historiography of the Portuguese in Sri Lanka: A Survey of the Sinhala Writings”, Samskrti XVII (1983), pp. 13-22.

de Silva, C. R. The Portuguese in Ceylon 1617-1638 (Colombo, 1972).

de Silva, C. R. “The Portuguese Revenue Register of the Kingdom of Kotte, 1599 by Jorge Florim de Almeida”, The Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, V (1975) pp. 69-153

de Silva, C. R. “Sri Lanka in the early 16th century: economic and social conditions”, in K. M. de Silva, ed., the University of Peradeniya, History of Sri Lanka, vol. II, Peradeniya, 1995, pp. 11-36.

de Silva, C. R. and de Silva, D. “The History of Ceylon (circa 1500-1658). A historiographical and bibliographical survey”, The Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, new series, III (1973), pp. 52-77.

de Silva, Daya, “A bibliography of manuscripts relating to Ceylon in the archives and libraries of Portugal”, Boletim International de Bibliografia Luso-Brasileira, VIII (1967), pp. 533-552, 647-675; IX (1968), pp. 84-157, 499-527.

de Silva, Daya, The Portuguese in Asia: An Annotated Bibliography of Studies on Portuguese Colonial History in Asia 1498-c. 1800 (Zug, 1985).

de Silva Jayasuriya, Shihan Tagus to Taprobane: Portuguese Impact on the Socio-Culture of Sri Lanka from 1505 (Dehiwala, 2001).

de Queyroz, Fernão, Conquista Temporal e Espiritual de Ceylão (Colombo, 1916).

de Queyroz, Fernão, The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Sri Lanka, S. G. Perera trans., (Colombo, 1930).

do Couto, Diogo and de Barros, Joao, Decadas da Asia, 24 vols. (Lisbon 1777-88).

Documenta Indica, ed. José Wicki, 14 vols. (Rome, 1948-1979).

Documentação para a História dqs Missões do Padroado Português do Oriente. Índia, ed. António da Silva Rego, 12 vols. (Lisbon, 1947-1958).

Documentos sobre os Portugueses em Moçambique e na África Central, 1497-1540/Documents on the Portuguese in Mozambique and Central Africa, 1497-1540, vol. III, (Lisbon, 1964)

Don Peter, W. L. A. Education in Sri Lanka under the Portuguese (Colombo, 1978),

Everaert, J. “Soldiers, Spices and Diamonds: Northerners in Portuguese India 1505-1590”, in Anthony Disney and Emily Booth, eds., Vasco da Gama and the Linking of Europe and Asia (New Delhi, 2000), pp. 84-104.

Ferguson, D. W., “The Discovery of Ceylon by the Portuguese in 1506”, Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, XIX (1907), pp. 321- 385.

Flores, Jorge Manuel “ A ‘Gift from the Divine Hand’: Portuguese Asia and the treasures of Ceylon”, in Helmut Trnek and Nuno Vassallo e Silva, eds., Exotica. The Portuguese Discoveries and the Renaissance Kunstkammer, Exhibition Catalogue (Lisbon, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, 2001) pp. 81-92.

Flores, Jorge Manuel, Os Olhos do Rei: Desenhos e Descrições Portuguesas da Ilha de Ceilão (1624, 1638) (Lisbon, 2001).

Flores, Jorge Manuel, Os Portugueses e o Mar de Ceilão, 1498-1543: Trato, diplomacia e guerra (Lisbon, 1998).

Flores, Jorge Manuel, Hum Curto Historia de Ceylan: Five Hundred Years of Relations between Portugal and Sri Lanka (Lisbon, 2000)

Franciscans and Sri Lanka, ed. W. L. A. Don Peter (Colombo, 1983).

Goonewardena, K. W. “Dutch Policy towards Buddhism in Sri Lanka: Some Aspects of its Impact”, in K. M. de Silva, Sirima Kiribamune and C. R. de Silva, eds., Asian Panorama: Essays in Asian History (New Delhi, 1990), pp. 319-352.

Goonewardena, K. W. Foundations of Dutch Rule in Ceylon (Amsterdam, 1958)

Gunawardane, Philip Sitawka Urumaya (Colombo, 1973)

Holt, John C. Buddha in the Crown: Avalokiteswara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka (New York, 1991).

Holt, John C. The Buddhist Vishnu: Religious Transformation, Politics and Culture (New York, 2004)

Holt, John C. “The Persistence of Political Buddhism”, in Tessa Bartholomeusz and Chandra R. de Silva, eds., Buddhist Fundamentalism and Minority identities in Sri Lanka (Albany, 1998), pp. 192-194.

Ilangasinha, B. M. Buddhism in Medieval Sri Lanka (New Delhi, 1992).

Jackson, Kenneth David De Chaul a Batticaloa. As Marcas do Império Português na Índia e no Sri Lanka (Ericeira, 2005).

Jackson, Kenneth David Sing Without Shame: Oral Traditions in Indo-Portuguese Creole Verse (Amsterdam and Macau, 1990).

Journal of Spilbergen: The First Dutch Envoy to Ceylon, 1602, ed. K. D. Paranavitana (Colombo, 1997)

Kustantinu Hatana, ed. S. G. Perera and M. E. Fernando (Colombo, 1932)

Maha Hatana, ed. T. S. Hemakumar (Colombo, 1964)

Malalgoda, K. ‘Concept and Confrontations: A Case Study of agama” in Michael Roberts, ed., Collective Identities Revisited, vol. 1 (Colombo, 1997), pp. 55-78.

Matatakkalappu Manmiyam, ed. F. X. C. Nadarajah (Colombo, 1962)

Mirando, A. H. Buddhism in Sri Lanka in the 17th and 18th Centuries (Dehiwala, 1985).

Paranavitana, Senerat “The Emperor of Ceylon at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in AD 1505”, University of Ceylon Review, XIX (1961), pp. 10-29.

Perera, S. G. A History of Ceylon, revised by Fr. V. Perniola (Colombo, 1955)

Perera, S. G. History of Ceylon: The Portuguese Period 1505-1656 (Colombo, 1932).

Perera, S. G., ed. and trans., The Tombo of the Two Korales, (Colombo, 1938).

Pieris P. E. ed., The Ceylon Littoral 1593, (Colombo, 1949).

Pieris P. E. ed., The Kingdom of Jaffnapatam, 1645, (Colombo, 1920).

Pieris P. E Ceylon: The Portuguese Era being the History of the Island for the Period 1505-1658, 2 vols. (Colombo, 1913-1914)

Pieris P. E. ed., “Kiraveli Pattuva, 1614”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon Branch), XXXVI/100 (1945), pp. 141-185.

Portuguese Regimentos on Sri Lanka, ed. T. Abeyasinghe (Colombo, 1975)

Prakash, Om Bullion for Goods: European and Indian Merchants in the Indian Ocean Trade 1500-1800 (Delhi, 2004).

Queré, M. “Beginnings of the Portuguese Mission in the Kingdom of Kotte”, Aquinas Journal, V (1988), pp. 80-85.

Queré, M. Christianity in Sri Lanka under the Portuguese Padroado, 1597-1658 (Colombo, 1995)

Queré, M. “Christianity in the Kingdom of Kotte in the First Years of Dharmapala’s Reign, 1551-1555”, Aquinas Journal, V (1988), pp. 160-165;

Queré, M. “Christianity in the Kingdom of Kotte during Dharmapala’s reign, 1558-1597”, Aquinas Journal, VI (1989), p. 70-78.

Rajasiha Hatana, ed. Ellepola H. M. Somaratna, ed. (Kandy, 1966).

Rajavaliya, ed. A. V. Suraweera (Colombo, 1976).

Rajavaliya, trans. B. Gunesekera, (Colombo 1900).

Rambukwelle, P. B. The Period of Eight Kings (Colombo, 1996).

Roberts, Michael Caste Conflict and Elite Formation: The Rise of a Karava Elite in Sri Lanka 1500-1950 (Cambridge, 1982)

Roberts, Michael Sinhala Consciousness in the Kandyan Period, 1590s to 1815 (Colombo, 2004)

Rogers, John D. “Post-Orientalism and the Interpretation of Pre-Modern and Modem Political Identities: The Case of Sri Lanka”, Journal of Asian Studies, 53 (1994), pp. 10-23.

Ribeiro, João, Fatalidade Histórica da Ilha de Ceilão, (Lisbon, 1836).

Rohanadheera, Mendis Dharma Parakramabahu: Prutugeeseen Mawu, Sinhale Vyaja Raajayaa ([Colombo], 1997)

Rohanadheera, Mendis 1506 Parangiya Gaalu Giya: Ithihasakarana Drushtikonayaki ([Colombo], 1999)

Rohanadheera, Mendis “Revised Chronology of Sri Lankan Rulers, circa 1500 AD: A Historiographical Perspective”, in R. A. L. H. Gunawardana et al, eds., Reflections on a Heritage: Historical Scholarship on Early Modern Sri Lanka (Colombo, 2000), pp. 255-282.

Sitawaka Hatana, ed. Rohini Paranavithana (Colombo, 1999).

Somaratne, G. P. V. The Political History of the Kingdom of Kotte, 1400-1521 (Colombo, 1975)

Strathern, Alan “Re-reading Queiros: Some Neglected Aspects of the Conquista”, Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities, XXVI (2000), pp. 1-28.

Strathern, Alan “Theoretical Approaches to Sri Lankan History and the Early Portuguese Period”, Modern Asian Studies, 38 (2004), pp. 190-226.

Subhramanyam, Sanjay “Iranians Abroad: Intra-Asian Elite Migration and Early Modem State Formation”, The Journal of Asian Studies, 31 (1992), pp. 340-363.

The Catholic Church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese Period, ed. V. Perniola, vol. 1 (Dehiwala, 1989)

Vassallo e Silva, Nuno “Jewels ‘in gold and stones’ from Ceylon”, Oriente, 2 (2002), pp. 23-36;

Walters, Jonathan S. “Vibishana and Vijayanagara: An Essay on Religion and Geopolitics in Medieval Sri Lanka”, The Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities, XVII & VIII (1994), pp. 129-142.

Winius, George W. The Fatal History of Portuguese Ceylon (Cambridge, MA, 1973)

END NOTES

[1] This is a revised version of a paper originally presented at a Workshop on Portugal-Sri Lanka Interactions sponsored by the American Institute for Sri Lankan Studies in Colombo on June 18, 2005. I am grateful for input from John C. Holt and Alan Strathern.

[2] Alan Strathern, “Theoretical Approaches to Sri Lankan History and the Early Portuguese Period,” Modern Asian Studies, 38 (10), 2004, pp. 190-226.

[3] João de Barros’ Decadas were first 1552-1615. Diogo do Couto’s Decadas were published between 1616 and 1784. Fernão Lopes de Castanheda’s Historia do Descobrimento e Conquista da India pelos Portugueses was published 1552-61 though his ninth book was printed for the first time only in 1929. Gaspar Correia’s work was published only in the mid-nineteenth century. Fernão de Queyroz’s Conquista Temporal e Espiritual de Ceylao was first published in 1916 and appeared in English translation in 1930. João Ribeiro’s Fatalidade Historia de Ceilâo was published in Portuguese only in 1836 though an adapted French version has been available since 1701.

[4] For a listing of these works see Daya de Silva. The Portuguese in Asia: An Annotated Bibliography of Studies on Portuguese Colonial History in Asia 1498-c. 1800, Zug, 1985. For a listing of the manuscripts see Daya de Silva, “A bibliography of manuscripts relating to Ceylon in the archives and libraries of Portugal,” Boletim International de Bibliografia Luso-Brasileira, Vols. VIII & IX.

[5] P. E. Pieris, The Ceylon Littoral 1593 (Colombo: 1949) and P. E. Pieris, “Kiraveli Pattuva,1614,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon Branch) XXXVI, 1945, pp. 141-185, provide a summary of the third volume of the tombo.

[6] The Tombo of the Two Korales, S. G. Perera ed. and trans. (Colombo: 1938).

[7] P. E. Pieris, ed., The Kingdom of Jaffnapatam, 1645 (Colombo: 1920).

[8]B. Gunasekera’s edition of the Rajavaliya was published in 1900 and the Mahavamsa (and Culavamsa), (first published in the nineteenth century) was published in English translation in the 1920s.

[9] Edited by C. Brito in 1879

[10] For example see Kustantinu Hatana (various editions, 1938). Paul E. Pieris played an important role in examining the Sinhala evidence. For a survey of Sinhala sources used during this time see C. R. de Silva, ‘The Historiography of the Portuguese in Sri Lanka: A Survey of the Sinhala Writings,’ Samskrti XVII (4), Oct.-Dec. 1983, pp.13-22.

[11]C. R. de Silva, “The Portuguese Revenue Register of the Kingdom of Kotte, 1599 by Jorge Florim de Almeida,” The Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, V, 1975, pp. 69-153. (Translation on pp 101-153) On the discovery of the manuscript see Daya de Silva, “A bibliography of manuscripts’ op. cit., VIII (3), p. 535.

[12] T. Abeyasinghe Portuguese Regimentos on Sri Lanka (Colombo: 1975).

[13] Jorge Manuel Flores, Os Olhos de Rei: Desenhos e Descriçoes Portuguesas do Ilha de Ceilão (1624- 1638) (Lisbon: 2001).

[14] P. E. Pieris, Portuguese Maps and Plans of Ceylon, 1650 (Colombo: 1926). Pieris was incorrect in dating it at 1650. Flores has concluded that it was a 1620s copy of the Madrid manuscript.

[15] E. Reimers, Constantino de Sa’s Maps and Plans of Ceylon, l624-1628 (Colombo: 1929).

[16] (Dehiwala: 1989-91).

[17] See for instance, José Wicki, ed., Documenta Indica, 14 vols (Rome: 1948-79), António da Silva Rego, ed., Documentaçao para a História dos Missöes do Padroado Português do Oriente. India, 12 vols (Lisbon: 1947-1958), and As Gavetas do Torre do Tombo, 10 vols (Lisbon: 1960-1974).

[18] (Lisbon: 1960-67). 3 vols.

[19] On Queyroz see, T Abeyasinghe, “History as Polimics and Propaganda: An Examination of Fernão de Queiros History of Ceylon,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Sri Lanka Branch, New Series, XXV, 1980-81, pp. 28-69 and Alan Strathern ‘Re-reading Queiros: Some Neglected Aspects of the Conquista,’ Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities, XXVI (1&2) 2000, pp. 1-28.

[20] Chapters on the Introduction of Christianity to Ceylon taken from the Conquista Espiritual do Oriente of Friar Paulo do Trinidade, Edmund Pieris and Achilles Meersman, trans. (Colombo: 1972).

[21] The Asgiri Talpatha that Mendis Rohanadheera claims to have ‘discovered’ was actually published in Sinhala in 1945.

[22] (Colombo: 1962).

[23] See for instance, Rajasiha Hatana, Ellepola H. M. Somaratna, ed. (Kandy: 1966), Maha Hatana, T. S. Hemakumar, ed. (Colombo: 1964). More recently Rohini Paranavithana edited the Silawaka Hatana (Colombo: 1999).

[24] Alakesvarayuddhaya, A.V. Suraweera, ed. (Colombo: 1965). Risiman Amerasingha has drawn our attention to a manuscript termed Sitawaka Rajjya Kaalaya that follows the Alakesvara Yuddhaya but gives some more details. See Risiman Amerasingha, Sitawaka Rajadhaniye Unnathiyeda Avanathiyeda Samahara Ansha Pilibanda Vimarshanayak (Colombo: 1998) pp. 2-10. The text is in his Aithihasika Sitawaka (Colombo: 1990) pp. 33-49.

[25] I refer to K. W. Goonewardena, Tikiri Abeyasinghe, Miguel Gunatilleke, W. L. A. Don Peter, Edmund Pieris and others, including myself. Martin Queré and Vito Perniola have lived so long in Sri Lanka that it is possible to argue that their vision too is influenced by Sri Lankan concerns.

[26] See Michael Roberts, Sinhala Consciousness in the Kandyan Period, 1590s to 1815 (Colombo: 2004); C. R. de Silva, “Beyond the Cape: The Portuguese Encounter with the Peoples of South Asia,” Implicit Understandings: Observing. Reporting, and Reflecting on the Encounters between Europeans and Other Peoples in the Early Modem Era, Stuart B. Schwartz, ed., (Cambridge: 1994) pp. 295-322; C. R. de Silva, “Algumas Reflexoes sobre o Impacto Português na Religião entre as Singaleses durante os Seculos XVI e XVII,” Oceanos, 34, April-June 1998, pp. 104-116.

[27] See her “Les Rois de Kotte au debut du XVIe siecle,” Mare Luso-Indicum, 1, (1971), pp. 65-96 and “A propos de l‘Inscription de Colombo (1501). Quelques observations sur le premier voyage de João de Nova dans l’Ocean Indien,” Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, XXVIII (1980), pp. 235-70.

[28] Jorge Manuel Flores, Os Portugueses e O Mar de Ceilao (Lisbon: 1998).

[29] There are some exceptions. See, Franciscans and Sri Lanka, W. L. A. Don Peter, ed. (Colombo: 1983).

[30] Risiman Amarasingha’s Sitawaka Rajadhaniyee Unnathiyeda op. cit. makes skilful use of Sinhala texts: to supplement evidence from the Portuguese sources

[31] saththiya vetham

[32] The Brito translation has the following sentence, not found in the Tamil text: ‘This took place in the month of Adi of the year Kara.’

[33] Anrique Anriques was a Jesuit who had served in the Fishery Coast in India. He accompanied the Portuguese viceroy on the expedition to Jaffna.

[34] The Portuguese original of this letter is in the Biblioteca da Ajuda 49-IV-5O, ff. 274-275 and it has been published in Documenta Indica, V pp. 6-12 and in English translation in The Catholic Church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese Period, Vol. 1, pp. 376-82.

[35] My translation from the Rajavaliya, A V. Suraweera, ed. (Colombo: 1976) pp. 219-20, 238.

[36] In his lectures to undergraduate students at the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya

[37] Alan Strathem, “ Theoretical Approaches to Sri Lankan History” op. cit. pp. 215-216.

[38] John C. Holt makes this argument in “The Persistence of Political Buddhism,” Buddhist Fundamentalism and Minority identities in Sri Lanka, Bartholomeusz and de Silva, ed. (Albany: 1998) pp. 192-194 and in Buddha in the Crown: Avalokiteswara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka (New York: 1991).

[39] See the differences between Sri Rahula and Vidagama Maitriya as depicted in A. H. Mirando, Buddhism in Sri Lanka in the 17th and 18th Centuries (Dehiwala: 1985) pp. 13-18. B. M. Ilangasinha sees it more as a clash on the practice of deity worship performance of magical rituals and the definition of the vocation of the monk, Buddhism in Medieval Sri Lanka (New Delhi: 1992) pp. 63-65, 125.

[40] T. Abeysinghe, “Portuguese Rule in Kotte, 1594-1638,” University of Peradeniya, History of Sri Lanka. Volume II, K. M. de Silva, ed. (Peradeniya: 1995) p. 129; Chapters on the Introduction of Christianity op. cit. p 180; C. R. de Silva. The Portuguese in Ceylon 1617-1638 (Colombo: 1972) pp. 240-241, 245; M. Queré, “Christianity in the Kingdom of Kotte in the First Years of Dharmapala’s Reign, 1551-155S,” Aquinas Journal, V (2), 1988, p. 163; M. Queré, “Christianity in the Kingdom of Kotte during Dharmapala’s reign, 1558-1597.” Aquinas Journal, VI (1), 1989, p. 73.

[41] C. R. de Silva, “Algumas Reflexoes” op cit.

[42] K. W. Goonewardena, “Dutch Policy towards Buddhism in Sri Lanka: Some Aspects of its Impact,” Asian Panorama: Essays in Asian History, K. M. de Silva et.al., ed. (New Delhi: 1990) pp..

[43] Kitsiri Malalgoda, “Mandarampura Puvata: An Apocryphal Buddhist Chronicle,” Paper presented at the Seventh Sri Lanka Studies Conference, Canberra, Dec. 1999.

[44] This is a difficult task but one path towards it might be a study of the differences in religious texts studied in the fifteenth century as against those that were emphasized in the eighteenth

[45] J. R. Carter, “The Origin and Development of ‘Buddhism’ and ‘Religion’ in the study of Theravada Buddhist Tradition,” On Understanding Buddhists: Essaya on the Theravada Tradition in Sri Lanka (Albany: 1993) pp. 9-25; K. Malalgoda, ‘Concept and Confrontations: A Case Study of agama,” Collective Identities Revisited, Michael Roberts, ed. Vol. 1 (Colombo: 1997) pp. 55-78.

[46] See for example speculation by John Holt that the destruction of the temple at Devinuwara by the Portuguese was a factor in the decline in the worship of Upulvan among Buddhists. John C. Holt, The Buddhist Vishnu: Religious Transformation, Politics and Culture (New York: 2004) p. 101.

[47] P. E. Peiris, Ceylon: The Portuguese Era being the History of the Island for the Period 1505-1658, 2 vols. (Colombo: 1913-14); S. G. Perera, History of Ceylon: The Portuguese Period 1505-1656 (Colombo: 1932).

[48] His Foundations of Dutch Rule in Ceylon, (Amsterdam: 1958) is still the definitive work on the end of Portuguese rule in Sri Lanka though it can be read with George W. Winius, The Fatal History of Portuguese Ceylon (Cambridge: 1973).

[49] T. B. H Abeyasinghe, Portuguese Rule in Ceylon 1594-1612, (Colombo: 1966).

[50] Philip Gunawardane, Sitawka Urumaya (Colombo: 1973).

[51] See P. B. Rambukwelle, The Period of Eight Kings (Colombo: 1996).

[52] See, W. L. A. Don Peter, Education in Sri Lanka under the Portuguese (Colombo: 1978) pp. 14-17.

[53] John D. Rogers, “Post-Orientalism and the Interpretation of Pre-Modern and Modem Political Identities: The Case of Sri Lanka,” Journal of Asian Studies, 53, 1994, pp. 10-23.

[54] See, Strathern, ‘Theoretical Approaches,” op. cit. pp. 218-220.

[55]See also M. Queré, “Beginnings of the Portuguese Mission in the Kingdom of Kotte,” Aquinas Journal, V (1), 1988, pp. 80-85 on the conversion of the sons of Bhuvanekabahu.

[56] Journal of Spilbergen: The First Dutch Envoy to Ceylon, 1602, K. D. Paranavitana, ed. (Colombo: 1997) p. 44.

[57] Joan Pau Rubéis, ‘Introduction’ Shifting Cultures: Interaction and Discourse in the Expansion of Europe, Henriette Bugge and Joan Pau Rubéis, eds. (Munster: 1995) p.6.

[58] Michael Roberts, op. cit. pp. 115-130.

[59] I owe this idea to Alan Strathern

[60] C. R. de Silva, Portuguese Rule, op. cit. p. 193

[61] K. W. Goonewardena, The Foundations of Dutch Rule, op. cit. pp. 142-143.

[62] Michael Roberts, Caste Conflict and Elite Formation: The Rise of a Karava Elite in Sri Lanka 1500-1950, (Cambridge: 1982).

[63] Fernão de Queyroz, The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon, S. G. Perera, trans. (Colombo:1930) p. 82. One might read this not only as a revolt against caste dress distinctions but also as a compromise between western and eastern dress by wearing both. This was also noticed in nineteenth century Sri Lanka.

[64] Michael Roberts, Caste Conflict and Elite Formation: The Rise of the Karava Elite in Sri Lanka, 1500-1931 (Cambridge: 1982) pp. 29-31

[65] Jorge Flores. Os Portugueses e O Mar de Ceilâo, op. cit.,

[66]See Dauril Alden, The Making of an Enterprise: The Society of Jesus in Portugal. Its Empire and Beyond, 1540-1750 (Stanford: 1996); J. Everaert, “Soldiers, Spices and Diamonds: Northerners in Portuguese India 1505-1590,” Vasco da Gama and the Linking of Europe and Asia, A. Disney, ed. (New Delhi: 2000) pp. 84-104.

[67] This was an idea sparked by a conversation with K. D. Paranavitana

[68] Jorge Flores. Os Portugueses e O Mar de Ceilâo, op. cit., pp. 116-120.

[69] See T. B. H Abeyasinghe, Portuguese Rule op. cit. pp. 74-79

[70] For some discussion, see Alan Strathern, “Theoretical Approaches,” op. cit. pp 194-204. For earlier times see Jonathan S. Walters, “Vibishana and Vijayanagara: An Essay on Religion and Geopolitics in Medieval Sri Lanka,” The Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities, XVII & VIII, 1994, pp. 129-142.

[71] On the importance of ritual and display see Michael Roberts, Sinhala Consciousness in the Kandyan Period, 1590s to 1815 ( Colombo, 2004) pp. 40-52.

[72] C. R. de Silva, “Portuguese Interactions with Sri Lanka and the Maldives in the Sixteenth Century: Some Parallels and Divergences,” Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities, XXVII & XXVIII, 2001-2002, pp. 1-23 and Alan Strathern, “Theoretical Approaches,” op. cit. pp 194-204.

[73] I owe this suggestion to Alan Strathern.

[74] See, for example, works by Tikiri Abeyasinghe and C. R. de Silva cited above

[75] Om Prakash, Bullion for Goods: European and Indian Merchants in the Indian Ocean Trade 1500-1800 (Delhi: 2004) esp. pp. 55-65.

[76] See for instance, Sanjay Subhramanyam, “Iranians Abroad: Intra-Asian Elite Migration and Early Modem State Formation,” The Journal of Asian Studies, 31(2), 1992, pp. 340-363.

[77] See, Nuno Vassallo e Silva, “Jewels ‘in gold and stones’ from Ceylon”, Oriente, 2, April 2002, pp. 23-36; Jorge Flores, ‘Uma mercé da mao divina’: A Asia Portuguesa e os Tesouros de Ceiläo,’ Exotica. Os Descobrimentos Portugueses e as Camaras de Maravilhas do Renascimento, Exhibition Catalogue, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum (Lisbon: 2001) pp. 81-92

[78] Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya, Tagus to Taprobane: Portuguese Impact on the Socio-Culture of Sri Lanka from 1505 (Dehiwala: 2001), Kenneth David Jackson, Sing Without Shame: Oral Traditions in Indo-Portuguese Creole Verse (Macau: 1989) and Kenneth David Jackson, De Chaul a Batticloa: As Marcas do Império Português na India e no Sri Lanka (Lisbon: 2005)

[79] D. W. Ferguson, “ The Discovery of Ceylon by the Portuguese in 1506,” Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, XIX, 1907, pp. 284-320 (with a supplement of documents pp. 321- 385)

[80] Ibid. pp. 298, 316-17

[81] Ibid. pp. 297ff, 389

[82] Ibid. pp. 302, 310

[83] Fernão de Queyroz, op. cit., p. 176.

[84] Fernão Lopes de Castanheda’s Historia do Descobrimento e Conquista da India pelos Portugueses, Manuel Lopes de Almeida, ed. (Porto: 1979). Castanheda left Portugal for India in 1528

[85] C. R. de Silva, “The First Visit of the Portuguese to Ceylon 1505 on 506,” Senerath Paranavithana Commemoration Volume, Prematilleke, Indrapala and Lohuizen van Leeuw, ed. (Leiden: 1978) pp. 218-220; Genevieve Bouchon in “Les Rois de Kotte au debut du XVI siecle,” Mare Luso-Indicum, Vol. II, 1971, p. 74 had also used Augur as a source and assumed that the date of the first encounter was 1506, though nine years later in 1580, she offered 1501 as an alternative. See fn 78 below.

[86] Reprinted in Documentos sobre as Portugueses em Moçambique a na Africa Central, 1497-1540/Documents on the Portuguese in Mozambique and Central Africa, 1497-1540, Vol. III, (Lisbon: 1964) pp 586-633.

[87] See Martin Quere, Christianity in Sri Lanka under the Portuguese Padroado, 1597-1658 (Colombo: 1995) p. 1; Risiman Amarasinha, Sitawaka Rajadhaniye op. cit., pp. 34; Jorge Manuel Flores, Os Portugueses e O Mar de Ceilao, op. cit., pp. 111-116. C. R. de Silva himself left the question of 1505 open in the University of Peradeniya: History of Sri Lanka, op. cit., p. 16 and O. M. da Silva Cosme opted for 1505 in his, Fidalgoes in the Kingdom of Kotte, Sri Lanka 1505-1656 (Colombo: 1990) pp. 19-20.

[88] Genevieve Bouchon, “A propos l’inscription de Colombo [1501]. Quelques observations sur le premier voyage de João da Nova dans l’Ocean Indien,” Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, 28, 1980, pp. 233-270.

[89] O. M. da Silva Cosme, Fidalgoes in the Kingdom of Kotte, op. cit. p 20. Another possibility is that this was a later inscription with an erroneous date.

[90] Jorge M. Flores, Os Portugueses e O Mar de Ceilão, op. cit. pp. 104-110

[91] S. G. Perera, A History of Ceylon, revised by Fr. V. Perniola, (Colombo: 1955) pp. 12, 15; H. W. Codrington, A Short History of Ceylon (London: 1947) pp. 94, 100.

[92] Rajavaliya, A. V. Suraweera, ed. op. cit, pp. 213-214.

[93] Senerat Paranavitana,, “The Emperor of Ceylon at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in AD 1505,” University of Ceylon Review, XIX, 1961, pp. 10-29.

[94] G. P. V. Somaratne, The Political History of the Kingdom of Kotte, 1400-1521 (Colombo: 1975) pp. 162- 175.

[95] See, C. R. de Silva, University of Peradeniya: History of Sri Lanka, Vol. II, op cit, pp. 13-14.

[96] Genevieve Bouchon “Les Rois de Kotte au debut du XVI siecle,” op. cit., esp. pp. 82-96.

[97] Cartas de Afonso de Albuquerque, Seguidas de Documentos que se Elucidam, R. A. de Bulhao Pato, ed., Vol. 1, (Lisbon: 1884) pp. 133-9. Also printed in Alguns Documentos da Torre do Tombo Acerca das Navegacoes e Conquistas Portuguesas, José Ramos Coelho, ed. (Lisbon: 1892) pp. 295-298. The translation is from Donald Ferguson, “The Discovery of Ceylon” op. cit. p. 373.

[98] Mendis Rohanadheera, Dharma Parakramabahu: Prutugeeseen Mawu, Sinhale Vyaja Raajayaa ([Colombo]: 1997), and “Revised Chronology of Sri Lankan Rulers, circa 1500 AD: A Historiographical Perspective,” in Reflections on a Heritage: Historical Scholarship on Early Modern Sri Lanka, R. A. L. H. Gunawardana et. al., eds. (Colombo: 2000) pp. 255-282.

[99] At a Workshop in Colombo in June 2005, Mendis Rohanadheera asserted that he had, up to that time, been unaware of Bouchon’s writings.

[100] Senerat Paranavitana had ascribed it to Parakramabahu VI (1412-67)

[101] Alakewarayuddhaya, A. V. Suraweera, ed. (Colombo: 1965).

[102] C. R. de Silva, “Beyond the Cape: The Portuguese Encounter with the Peoples of South Asia,” op. cit., pp. 310-313 in footnotes. 65 and 76.

[103] In a later work Rohanadheera asserts that two Sinhala princes who were refugees in Goa in the late 1580s probably wrote the Alakesvarayuddhya. There is no evidence for this, See, Mendis Rohanadheera, 1506 Parangiya Gaalu Giya: Ithihasakarana Drushtikonayaki ([Colombo]: 1999) p. 72. The English translation of the title that Rohandheera himself provides is Portuguese Taken for a Ride in Galle, 1506.

[104] Sitawaka Harana, op. cit. stanza 35

[105] G. P. V. Somaratne, The Political History of the Kingdom of Kotte. op. cit., p. 178.

[106] S. G. Perera, History of Ceylon op. cit. This was also the conclusion of Paul E. Pieris. See his Ceylon: The Portuguese Era, Vol. I (Dehiwala: 1992) (originally published in 1913) p. 32.

[107] João de Barros, Da Asia de João de Barros (Lisbon: 1973) p. 424. (Decada I, Livro V, Capitulo V)

[108] Fernão Lopes do Castanheda, Historia do Descobrimento, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 262.

[109] Gaspar Correia (Corréa), Lendas da India, Rodrigo José de Lima Felner, ed. (Lisbon: 1858) Vol. 1, pp. 646-50.

[110] Diogo do Couto, Decada V, Livro 1, Capitolo V.

[111] Mendis Rohanadheera, 1506 Parangiya Gaalu Giya op. cit.

[112] S. G. Perera, History of Ceylon, op. cit. pp 19-20

[113] C. R. de Silva, The Kingdom of Kotte and its Relations with the Portuguese in the Early Sixteenth

Century,” Don Peter Felicitation Volume, E. C. T. Candappa and M. S. S. Fernandopulle, eds. (Colombo: 1983) pp. 41-42.

[114] Jorge M. Flores, Os Portugueses e O Mar de Ceilão, op. cit. pp. 116-120. See also Jorge M. Flores, Hum Curto Historia de Ceylan: Five Hundred Years of Relations between Portugal and Sri Lanka (Lisbon: 2000) p. 50.

[115] Zoltán Biedermann, “Tribute, Vassalage and Warfare in Early Luso-Lankan Relations (1506-1543)”, in Fatima Gracias, Celsa Pinto and Charles Borges, eds., Indo-Portuguese History: Global Trends. Proceedings of the XIth International Seminar on Indo-Portuguese History (Goa, 2005), pp. 185-206.