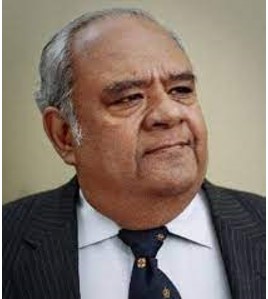

Text of keynote address by Sunil de Silva – at the 73rd Independence day celebration by Sri Lankan community groups in Sydney, Australia on 06 February 2020

[Text of keynote address by Sunil de Silva – at the 73rd Independence day celebration by Sri Lankan community groups in Sydney, Australia on 06 February 2020]

It is an honour to address an event organized by Sinhalese, Tamil, Malay, Moor, Buddhist, Hindu Christian and Islamic philosophies and faiths. Today’s combined effort augurs well and hopefully finds similar events in our motherland.

We are all siblings of one mother, we have our sibling rivalries, ‘I can run faster than my brother, I ‘am better than my sister at mathematics, I ‘am prettier than my elder sister’ but when it comes to celebrating the mother’s birthday, they all get together in baking the cake and preparing the food, and all join in singing ‘Happy Birthday’

INDEPENDENCE

What is Independence in the sense of a sovereign nation being ‘Independent’

In today’s Global context – the precepts of International law and the dictates of moral compulsion discourages any State however powerful and however wealthy, from acting without restraints. It is only within these para meters that a sovereign state can conduct its affairs as the people of that state require the state to conduct its affairs.

Where a state is ruled by foreign powers – Colonised – the polices are determined externally – some Colonisers were reasonably benevolent – only supping of the nations’ resources like the proverbial bee – others were rapacious plunderers.

We in Sri Lanka have gone through these phases. Even after Independence in 1948 a few external controls bound our state till 1972 when Sri Lanka became a republic, and the position of the Governor General was abolished.

Let us leave that discussion for another day.

My brief today is the acknowledgement of the National Heroes who made even the limited overthrow of the Colonial rule and not an analysis of whether the ‘Independence’ was absolute’ or ‘conditional’

On February 4 1948 Ceylon [as we then were] had a two chamber, bicameral legislature, a House of Representatives of 101 members. 95 elected by popular vote and 6 appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister. The elected Members of the lower house was increased to 145 by the 4th Amendment to the Constitution.

The six appointed members were usually from the European and Burgher communities, and from Indian Tamil and Muslim or Malay Communities. On occasion a member was nominated to represent an unrepresented cast.

The Senate consisted of 30 members, 15 elected by the House of Representatives and 15 appointed by the Governor General.

The Governor General was the representative of the Monarch in Britain. However, the Prime Minister and the Parliament became increasingly powerful and the Governor General became more of a figurehead.

I recall a Member of Parliament wanting to move a resolution that the Governor General’s salary be reduced to Seven Rupees Fifty Cents. Asked how he arrived at that figure he responded ‘That is cost of a rubber stamp’

Lanka – Thambapanni – Taprobane – Ceylon -Sri Lanka

Human remains and archeologically excavated and have been scientifically dated. They have been designated as those of the Balangoda Man and scientifically dated to be about 125,000 in antiquity. These Mesolithic hunter gatherers lived in caves, such as the Batadombalena and Fa Hien Caves.

There also was evidence that barley and oats had been grown on the Horton Plains around 15,000 BC,

Granite tools, remnants of earthenware and human remains dated to be 6000 BC have been discovered at Warana Rajamaha Vihare

So, the land we call Sri Lanka – the Resplendent Isle – supported human life spread over different parts of the country. Around the sixth century BC, these indigenous populations were augmented by regular arrivals from India, mostly from Bengal.

Our recorded history spans over two thousand five hundred years – we base our historical narrative on Pali chronicles like the Mahavamsa, Deepawansa and Culavamsa. These records show the emergence of the Sinhalese and the introduction of Buddhism. It is of course true that recorders of history glorify those Rulers who the writer approves at the expense of the others who were less acceptable. We need to find independent corroboration by dating inscriptions and human and other remains to give us a clearer picture.

That said, it is undisputed that we enjoyed

One thousand four hundred years of the glory of the Anurahdapura period 377 BC to 1017 AD and two centuries of the grandeur of the Polonnaruwa period. Interspersed with invasions and Tamil rulers like Elara.

We had ‘domestic’ ‘indigenous’ rulers, whether benevolent or otherwise, united or divided into kingdoms and regions but rulers of our own.

Did the Kings have uncontrolled power?

Were they not bound by divine or philosophical constraints?

When we quote ‘devo vassatu kaalenea’ The Gods in our Constitution, – does it not imply that unless

‘…governments, rulers and kings be righteous…’ they cannot expect ‘… the gods to shower rain in due season and ensure the right conditions for good fortune.

Through our ancient and glorious past, we were ruled by Kings – some good and others not so good. Good or bad, they were ‘our kings’ Arab traders, Chinese merchants and mendicant monks Fahien, IIbn Batuta, Marco Polo visited us, but did not interfere with our way of life.

The story changed in 1505 –

In 1505, an ‘ill wind’ blew a Portuguese Galleon to shelter in our natural harbour at Galle and very soon they took control of our maritime provinces by force of arms. The Portuguese infused some aspects of western life and religion. Bread, Wine mode of dress, Kamisa, Kaba Kurththu, Sapththu, Thoppi shoes and almirahs to store the garments.

In 1658 we sought the aid of the Dutch to rid us of the Portuguese, but the change of pillow did not ease the headache. The Dutch organized a legal structure for land and civil law, with Thombu’s for record keeping and Roman Dutch Law as civil laws.

However, our Kandyan Law, Thesavalami, and Muslim Law, the Customary Laws remained applicable to those customarily governed by those laws. [This is a subject too fraught with issues to be discussed at a forum such as we have today]

The British arrived in 1796 and by the treaty of Amiens in 1802 annexed most of our country as a Colony – attempts by the British forces to capture Kandy was repulsed by heroic battles of the Sinhalese forces and the rugged terrain.

It was thirteen years later that internal squabbling fomented by the British among the rulers of the Kandyan aristocracy that enabled the British to establish rule over the whole country. Foreign powers seeking control fomenting internal division is a danger to which we must remain vigilant even today.

At the time of the Kandyan convention 1815, Sinhalese law was the common law. It was customary law, known to the people. Our law was found in Sannasas – Palm Leaf Inscriptions – later codified as the Niti-Niganduwa. Justice was administered by a judge and marred by no sophisticated interpretation. There were no lawyers then!

The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka was established in 1801 with jurisdiction over all parts of the Country except the Kandyan Kingdom. In the local courts, civil servants dispensed justice, seeking assistance of the chiefs, and started recording and documenting customs that were recognised as law.

The British ruled our land and people to be useful to them – English – Arithmetic – Geography to make us useful clerical staff – Dictation – Spelling- Copybook script and Secretarial skills to make us competent secretaries. No subjects useful for the development of the potential in the country were on the curriculum.

The land was used to cultivate coffee, tea, rubber and coconut with marginal concern for conservation and sustainable use.

The Sri Lankan path to independence relied on parallel streams.

The religious and cultural uprisings, Violent rebellions- Sophisticated negotiations and the impact of the liberation movements in India.

History shows that – foreign rulers are often overthrown by insurrections and rebellions. We in Sri Lanka have had our share of rebellions. Keppetipola Disawe signed the Kandyan Covention in Sinhala to signal his disapproval of the treaty, and Wariyapola Sri Sumangala is credited with having hauled down the Union Jack and hoisting the Lion Flag in its place.

Armed uprisings, the Uva Rebellion of 1818 and the Matale Rebellion of 1848. Weera Puran Appu, Ven Kudapola and Gongalegoda Banda are credited as the leaders of the peasant revolt. Ven Kudapola was executed by a firing squad for what the British considered treason.

The Matale revolt was more a refusal by the peasants to be employed as labour in the coffee and tea plantations and induced the British to indenture labour from India.

Around the same period negotiations with the British was resulting in a degree of self rule trickling down from the British rulers.

The Colebrooke–Cameron Commission was appointed in 1833 as a Royal Commission of Eastern Inquiry by the British Colonial Office, ‘to assess the administration of the island of Ceylon and to make recommendations for administrative, financial, economic, and judicial reform. The commission comprised William MacBean, George Colebrook and Charles Hay Cameron. Cameron was in charge of investigating the judicial system. The legal and economic proposals made by the commission in 1833 were adopted.

They signalled the first manifestation of constitutional government. Though inadequate, it was a step in the right direction towards the commencement of a uniform system of justice, education and civil administration.

The attempts by Governor Fredrick North in 1802 to abolish Rajakariya the ancient system by which the citizens were compelled to render unpaid service to the king for the use of land and natural resources which belonged to the king with a land tax was resisted by the people and the old system recommenced till 1832 when it was abolished as recommended by the Cameron-Colebrook Commission.

On the recommendations of the Commission, the Colonial administration set up the Legislative Council and the Executive Council in March 1833 as the introduction of scheme of representative government in our country. An Executive Council, consisting of the Governor and five senior British Officials.

As a second step in 1924 the Manning Reforms added four unofficial members, they functioned until the Donoughmore Constitution. In 1931 on the recommendations of the Commission both Councils were abolished and replaced with the State Council and the Board of Ministers.

The Donoughmore Commissioners had been appointed by the Secretary of State, Sydney Webb, who selected Commissioners who shared his ideas that the British Empire be more equitable and socialist, and expected the Donoughmore Commission to devise a mechanism for every community in the country to exercise power and enjoy prosperity.

The Commission established adult universal franchise in Ceylon before any of the ‘non-caucasian’ colonies enjoyed the right of one adult one vote. Sadly, the ‘so called’ elite members of all the communities in Ceylon glanced askance at power sharing with the ‘non-elite’

I would now switch back to what was occurring in the Country during this period of transition

The Ceylon National Congress (CNC) was founded to agitate for greater autonomy but split up between one section that sought independence by gradual modification of the status of Ceylon; and the more radical groups associated with the Colombo Youth League, Labour movement of Goonasinghe, and the Jaffna Youth Congress who sought complete self rule, following the ‘Swaraj’ movement of Jawaharlal Nehru and Saojini Naidu in our giant neighbour – India.

Our efforts to achieve independence was somewhat hampered by internal conflicts, [this is a nest of hornets which I do not propose to stir]

The leaders D.S. Senanayke, Baron Jayatilleke, Oliver Gunatilaka, Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam, Dr C.W.W. Kannagara, and G.G. Ponnambalam were among those whose pressure demanding autonomy for Ceylon was having effect.

Those who were insistent on demands for ‘full’ an ‘immediate independence’ were led by the Lanka Samasamaja party stalwarts Dr. N.M. Perera, Dr. Colvin R de Silva, Philip Gunrwardena, Leslie and Viviyen Gunawardena, Robert Gunewardena, Edmund Samarakkody, Don Alwin Rajapakse [the father of two Presidents, Mahinda and Gotabaya Rajapakse], and K. Natesar Iyer. The others who contributed to the efforts were George E de Silva, B.H. Aluvihare, D. P. Jayasuriya, A. Ratnayake and Susantha de Fonseka.

There were peripheral movements by S. J. V. Chelvanayagam and his party.

At the same time D. S. Senanayke and Oliver Gunatilleke used the economic lever of contributions to the British War effort with persuasive skill towards achieving their objective. J.R. Jayewardena and Dudley Senanake contemplated collaboration with the Japanese as an alternative.

A third stream running parallel was the campaigning by the Buddhist revivalists, Anagarika Dharmapala, Henry Olcott, D.E. Henry Pedris, C.A. Hewavitharana, Arthur V Dias, Henry Amarasuriya, Dr W.A.de Silva, Edwin Wijeratne, A.E. Goonesinghe, Piyadasa Sirisena, John de Silva.

Anagarika Dharmapala left the country due to harassment by a hostile press and his work was carried on by Walisinghe Harischandra, Gunapala Malalasekera, and L.H. Mettananda.

The Inspector General of Police Herbert Dowbiggin [of Bracegirdle notoriety- he acted on the pressure by the white plantation Raj to arrest and detain a white skinned activist but failed to hold him against an habeas corpus writ] who was accused of using commerce related Sinhala Muslim clashes of 1915 to discredit the revivalist movement and to place the leaders under arrest. The riots of 1915 had a purely commercial base but was dragged out as a ‘racial confrontation]

Sir James Peris is credited with having drafted a memorandum cataloging these atrocities and with Ponnambalam Ramanathan and E.W. Perera and then smuggling it to London in the sole of his shoes, to evade police surveillance and delivered it to the Secretary of State for the Colonies

Perhaps another factor that hit the economic interests of the British in Ceylon was the Estate Strikes in 1939 reaching a peak in the Mool Oya strike supported by the LSSP. Govindan a worker was shot by the Police and Dr Colvin R de Silva ran the claim by the widow before the Commission of Inquiry and exposed the complicity of the Police and the white planters in the shooting.

The consequent spread of strikes to other parts of the plantation areas and reached a climax in the Wewessa Estate.

The LSSP continued its agitation resulting in N.M.Perera, Colvin R de Silva, Philip Gumewardena and Edmund Samarkkody being arrested. The party continued ‘underground’ with Doric de Souza, Reggie Senananyake and Leslie Gunewardena organzing strikes in several key commercial institutions.

We must acknowledge that poets P.B. Alwis Perera, The Tibetan Ven S. Mahinda, Ananda Rajakaruna, the author of the poem Sinha Kodiya – Lion Flag, G.H. Perera all made substantial contribution to raising the fire of the demand for liberty at grass root level.

The Japanese bombed Colombo in April 1942 and in the ensuing confusion the incarcerated LSSP leaders escaped and took refuge in India.

While the LSSP was increasing the pressure on the Government, the constitutionalists led by D. S. Senanayake succeeded in winning independence. The Soulbury constitution was essentially what Senanayake’s board of ministers had drafted in 1944. The promise of Dominion status and independence itself had been given by the Colonial Office.

A final and perhaps conclusive effect was the increasing demand for liberation in our giant neighbor India.

The confluence of the steady flow of the several the tiny rivulets spread over century and a half that have now swelled into a mighty river that would brook no opposition in its relentless urge towards the ocean of national freedom and socialism.

Dominion status followed on 4 February 1948, with D. S .Senanayke becoming the first Prime Minister of Sri Lanka. There were military treaties with Britain, as the upper ranks of the armed forces were initially British, and British air and sea bases remaining intact. From about 1950 the bases were taken over by the Sri Lankan Forces.