The Spin | Hutton and Carson: cricket prodigies who took different paths after 1937 – by Simon Burnton

England and New Zealand met at Lord’s this week 83 years ago with two gifted young batsmen in their ranks

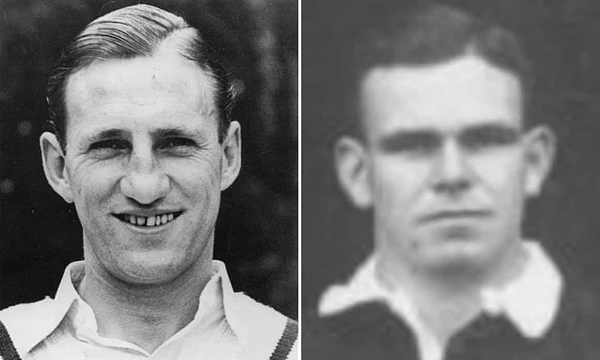

England’s Len Hutton (left) and New Zealand batsman Bill Carson. Photograph: Alamy

Source: Guardian

The first Test between England and New Zealand at Lord’s, which started on this week in 1937, was interesting for several reasons, none of them apparent to Neville Cardus at the time. “The engagement will be a Test match only in name,” he wrote in his preview for the Guardian. “None of us would expect Derbyshire to give England a good match; yet Derbyshire are a better team than New Zealand. The MCC should put a limit to the occasions on which a cricketer in this country is able to pick up ‘international’ colours almost for nothing.” England, he wrote, “have everything to lose and nothing to gain in Test matches which provide a test only for one side”, and there would be few benefits for anyone involved. “If today Hutton should score a hundred the innings will count for less than a hundred in our everyday county matches,” he wrote. “And if he should score nothing at all the failure will mean nothing.” Which is just as well, as he did score nothing. After a 30-minute duck in his first ever Test innings he improved significantly in the second, scoring one. The selectors obviously decided that Cardus had a point and stuck with him, he scored a century in the first innings of the second Test and the rest is history.

|

Streams, spinners and bubbles: counties ponder all options for restart |

Len Hutton had turned 21 just a few days earlier – it is, in fact, the 104th anniversary of his birth on Tuesday – and the young opener was the talk of English cricket. In the buildup to his first Test he had scored 136 against Kent, 271 against Derbyshire and 153 against Leicestershire in successive matches, but the hype about his abilities had been building for years. In fact six had passed since the Sheffield Daily Telegraph’s report on Yorkshire’s first practice session after the winter break had declared that “the most interesting youngster at the nets was Leonard Hutton, who is only 14 years old”, who despite being “tall and frail-looking at present” was causing some excitement. “The verdict is unanimous – ‘a county batsman of the future’ – and it will be interesting to watch his progress,” they wrote. “He certainly shaped with style and confidence yesterday.” Two years before Hutton’s England debut, Herbert Sutcliffe, another child of Pudsey, had predicted in his book For England and Yorkshire that Hutton would star for his country. “Hutton comes from Pudsey. I am from Pudsey too, and that little village has had continuous representation in the Yorkshire team for the last 46 years,” he said in 1937. “I am getting to the sere and yellow now. At any rate the selectors thought so last year and I don’t expect I shall be playing in first-class cricket for very much longer. It may be next year or it may be the year after, but it is bound to come. I am getting near the end of my tether as far as first-class cricket is concerned, but Hutton is there to carry on.” And carry on he did, for 79 Tests and 513 first-class matches, not retiring until 1956. Just a couple of weeks after Hutton’s birth in Pudsey, a child was born on the other side of the world whose status as the English summer of 1937 started was as similar to Hutton’s as his age. Bill Carson was another prodigy, who in 1932-33, aged just 15, scored more than 1,000 runs in senior cricket for Gisborne and by then had already been spotted by the Auckland chairman Hugh Duncan, who brought him north the following year. Though his cricketing ascent was delayed somewhat by a leg injury sustained in 1936 (when he was named one of the five most promising players in the country by the Rugby Almanack of New Zealand) the following summer he rocketed to prominence. |

Len Hutton, pictured circa 1955. Photograph: Getty Images

In his second appearance in the Plunket Shield, against Otago, he came in with Auckland at 25-2 and proceeded to score 290, then the second-highest individual total in the competition’s history and the second-highest maiden first-class century in the history of the game (by two runs). “His innings was sound yet brilliant, marked by such speed and judgement combined as to be exhilarating to watch,” wrote the New Zealand Herald. He and Paul Whitelaw put together a partnership of 445, a world record, and he proceeded to score another double century in his next game, and 194 against Wellington in his next first-class match. “He is only 20 years old, but his name is already a household word so far as cricket in New Zealand is concerned,” the former Kiwi wicketkeeper Ken James, then playing for Northamptonshire, wrote as the touring party arrived in England. “In this, his first season of big cricket, he has jumped right into the limelight by his remarkable scores in representative matches. He is a spectacular left-handed batsman, who believes in hitting the ball hard. His defence is attack from the start, and when he does get set he may be relied upon for a scintillating display of forceful shots all round the wicket.” But the careers of Hutton and Carson were to diverge completely over the course of that summer. Carson never flourished, averaged only 19 across the tour, and along with the 32-year-old Jack Lamason was one of only two players not to get picked for any of the Tests. The following year, as Hutton scored 364 against Australia at the Oval, Carson went on the All Blacks’ tour of Australia, but struggled with injuries and didn’t play any Tests in that sport either. That was New Zealand’s final tour in either of his sports before the outbreak of the second world war, when Hutton was kept away from combat in the physical training corps while Carson was thrown straight into it with the New Zealand artillery. His service took him to Greece, across Africa and finally to Italy, where he suffered serious wounds near Florence in July 1944. He died of jaundice that October, while on a boat heading home.

After his death CG Sinclair, who served under him as a gun sergeant, wrote about life under his command, which perhaps inevitably for a double All Black featured a lot of physical activity. “When his troop took part in the chase from Bardia to Tripoli, part of the equipment that jolted across the desert on a truck were two basketball posts,” he wrote. “War or no war, Bill was not going to be caught without facilities for sport.” For all his achievements Carson was, wrote Sinclair, “quiet to the point of shyness”, but that did not stop him being seen as a natural leader. “He had a wonderful, almost unbelievable influence on men during times of stress,” Sinclair wrote. “Merely to see him standing quietly behind the guns, or chatting to the men, was enough to put new spirit and determination into battle-weary soldiers. Of him it can truly be said, he was a splendid example and a real inspiration.” Eighty-three years ago this week Hutton and Carson were celebrating their 21st birthdays or soon to do so, brimming with talent and potential, preparing for their first Test series and hopeful of a lifetime of continued achievement. Their stories now serve as the starkest reminder that form, and life itself, can be unexpectedly fragile. |

How cricketers kickstarted Battleships crazePerhaps Hutton would not have got his chance in the summer of 1937 had the Kent opener Arthur Fagg not taken ill with rheumatic fever during England’s tour of Australia the previous winter, forcing his early return home. Just 21 at the time, he did not play again all year, and only played one more Test. While in Australia, however, he did find time to introduce a then-obscure game, with the Mirror giving him credit for “starting a craze called ‘Battleships’”. “Battleships is a game for two players,” they explained. “You rule out a number of squares on a piece of paper, draw ships in certain of the squares, and your opponent, who doesn’t know where your ships are, has to guess in which square they figure and sink them. The English cricketers have taken up Battleships in a big way and have started the craze in all parts of Australia. The best Battleships player is [Yorkshire spinner] Hedley Verity, who applies the same deep thought to it that he does to his bowling. His star performance to date is a defeat of [Middlesex’s Walter] Birdie Robins in six straight games on one of the many days that rain interfered with cricket. “Admiral” Verity is what they call the Yorkshire bowler now, while Robins is known as the “Swiss Admiral”. After the latter’s six losses in major naval engagements, Robins suggested calling a conference of the Powers to put an end to naval warfare.” The more familiar plastic version of Battleship was introduced in 1967 and has since sold more than 100m units. |

No Comments