An extreme experience – A Diagonal Journey across Sri Lanka with Sir Christopher Ondaatje – PART ONE – Text and pix by Lalith Seneviratne

I first met Sir Christopher Ondaatje in 2004 when I was in London. He comes from the famous Ondaatje family (his brother Michael is the author of Running in the Family) and Christopher himself left Ceylon in 1947 to go to school in England, spent five years in the City of London and then went to Canada where he made a fortune – first in finance, and then in publishing.

A lot has been written about Christopher and his business career in Canada. He is an enigmatic man. At the height of his financial power he sold all his companies in Canada and returned to his first love – writing and exploration. He has written a number of books, but the book closest to his heart is The Man-Eater of Punanai (1992) about the man-eating leopard that terrorised the tiny village of Punanai in the early 20th century until an English tea planter Shelton Agar shot it. Far from being only the story of this cunning leopard, Ondaatje uses the story of his return to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) after 38 years – to pick up the pieces of his early family life and to use the story of the man-eater as a metaphor for his relationship with his tyrannical but much-loved father. It is a classic that has sold over a 100,000 copies and describes a way of life that has now completely disappeared on the Island that he loves so much. The book is a parable and a love story.

Anxious to meet him I wrote Ondaatje a letter in 2004 and suggested a meeting in London. Not surprisingly, he wrote back and invited me to have lunch with him at Carafini – his favourite Italian restaurant on Lower Sloane Street – where he lives in London. I told Ondaatje then in 2004 that I was anxious to do an article on him and persuaded him to return to Sri Lanka to do a journey of discovery with him. This is the story of that journey.

Ondaatje is a man of many colours. Although a respected Dutch-Burgher family – the Ondaatjes are in fact Brahmins from North India that followed Shah Jahan (reigned from 1628 to 1658) and conquered South India. The original Ondaatje was a man in Shah Jahan’s court who eventually became Physician to the King of Tanjore (present day Thanjavur). When in 1659 the Dutch Governor of Ceylon, Governor Adriaan van der Meyden’s wife became incurably sick – presumably from cholera – he sent for Ondaatje who came to Ceylon and cured her. In return the Governor gave Ondaatje much land in Kotte, and Ondaatje stayed on the Island and married a Portuguese Lady in Court – Magdalena de Crooz.

That was the start of the Ondaatje dynasty. They were clever people, committed to literature and learning, and to religion. Ondaatje, whose original name was Ondachi, converted to Christianity, and one of his descendants was the first person to translate the Bible into Tamil. The Ondaatjes intermarried, usually with Europeans, and almost certainly the most famous Ondaatje was Peter Philip Juriaan Quint Ondaatje who left Ceylon when he was 12 years, on a scholarship to a university in The Hague, sponsored by a burgomeister Hendrik Hooft, and became head of the Patriot Party in Holland, and led the uprising against the House of Orange (ca. 1785). He became a powerful politician, was exiled to France when the Patriot Party and the supporting Austrians were overthrown, but returned to Holland with the advent of Louis Napoleon (Bonaparte’s brother) in 1806. At that time Quint Ondaatje was one of the six most powerful people in Holland and for a while ran the Dutch East India Company until Bonaparte, suspected of being jealous of his brother’s popularity in Holland, returned him to France and exiled Ondaatje to Java. He died there.

Sir Christopher Ondaatje is a direct descendant of the original Ondaatje (1659) and is proud of his heritage. There have been many Ondaatjes in Ceylon and Sri Lanka, lawyers, politicians, authors, and members of the Church – in particular, St. Thomas’ in Gintupitiya. There is biographical information on many of these Ondaatjes, the most recent being Michael Ondaatje, Christopher’s younger brother, who wrote Running in the Family (1982). The best of Christopher Ondaatje’s books are The Man Eater of Punanai and Woolf in Ceylon.

Ondaatje, now 85 years, lives in London and The Bahamas with his wife Valda. Their three children are grown up and live in California and Greenwich, Connecticut – in the USA, and in England.

Return to Sri Lanka

It wasn’t difficult for me to convince Ondaatje to return to Sri Lanka – the problem was when and for how long. Ondaatje is busy. He is involved with many organisations – particularly, the Royal Geographical Society, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Somerset County Cricket Club. It has taken 14 years for me to organise the diagonal journey binding together many of his famous haunts such as the Yala Game Sanctuary, Gal Oya, Sigiriya, Anuradhapura, Wilpattu National Park, and eventually Colombo.

My wife Ayanthie and I met Sir Christopher and Lady (Valda) Ondaatje at the Colombo Airport about 1 pm when their plane from London arrived. I had not seen Christopher for four years. Now 85 years old, I was amazed to see that osteoarthritis had affected his feet so that he now walked with the use of a stick. However, his enthusiasm was not diminished and we piled into our van and took the long three and a half hour journey to Tangalle where we had booked rooms at the Anantara Peace Haven. I had recommended a three-day rest to recover from the accumulated jet lag. It was quite overcast when we arrived – but we had time for a Sri Lankan dinner of hoppers and four or five curries which we washed down with some coconut arrack and king coconut water (thambili). We went to bed early that night and the Ondaatjes slept late.

Surprisingly, one of the first things that Christopher wished me to do was to go to a roadside cobbler in Tangalle to get his old safari boots fixed – as the soles were coming apart. He explained that he had not used these boots since 2004 when he was last on the Island. As he explained a fundamental rule for any arduous journey was to have comfortable footwear. While we left the boots to be fixed Christopher also forced me to take him to the local ayurvedic dispensary where he bought some oil made from the Mee tree seed (mousey mi or Madhuca longifolia)– a known aid for arthritis. Christopher continues to passionately believe in the healing powers of ayurvedic medicine in Sri Lanka. We collected the boots around 4 pm, went back to our hotel and had a relaxed discussion of our plans for the next day which included a visit to the Yala Game Sanctuary and the Ondaatje Bungalow (a 1992 gift from Sir Christopher to Yala) as well as a return to Hambantota to witness the reconstruction of the old harbour which took such a catastrophic toll on the morning of Boxing Day December 26, 2004. A return to Hambantota was a sensitive issue for us because we knew that the previous Rajapaksa Government had, in return for help from the Chinese Government to end the civil war in May 2009, allowed the Chinese Government to build its own deep-water harbour in Hambantota – a somewhat criticized gesture.

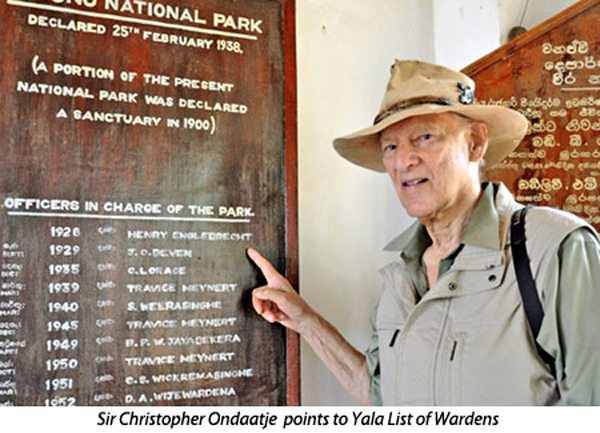

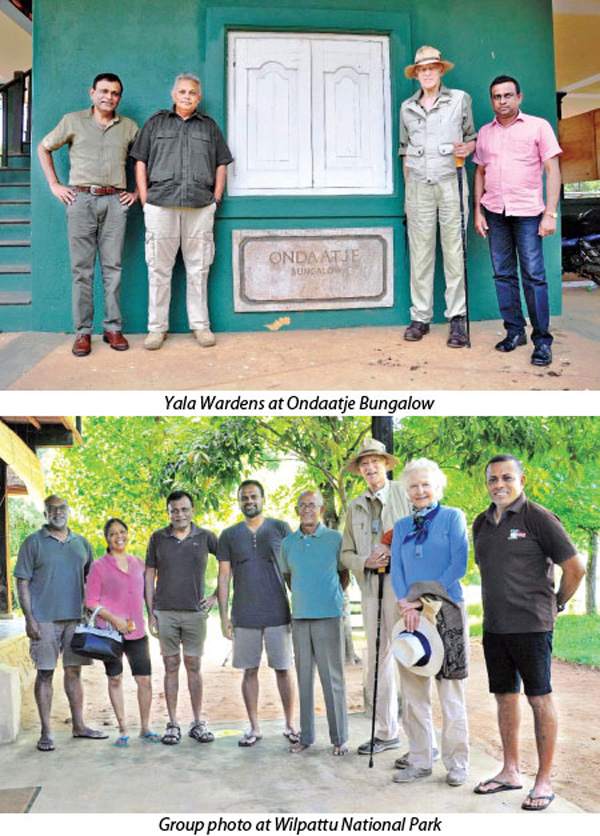

The next day, Christopher and I left at 8 am and drove straight to the Yala Game Sanctuary main office where we had a meeting with the wildlife personnel – including Warden Siyasinghe, Deputy Warden Ranjith Sisirakumara, and former Director General of Wildlife Dr Sumith Pilapitiya. Many sensitive political issues were discussed, and the problems ensuing from the explosion and popularity of wildlife tourism in Yala. Booking Park bungalows was difficult, there were not enough trackers available to service the Park attendance, and the growth and power of the jeep drivers were making wildlife viewing uncomfortable. We made a separate visit to the Ondaatje Bungalow, which was undergoing some re roofing and plumbing. We were glad to hear that the Bungalow continued to be a popular destination and had served its purpose well in that part of the Park on the road to Kataragama where squatters had posed a dangerous threat to the Park boundary.

An emotional event

Our return to the Hambantota Rest House around 3pm was an emotional event. The aftermath of the December 26 2004 tsunami, where the old pier had given way to a massive breakwater of stone across the mouth of the old Moorish harbour, was shocking. Several new buildings had been built immediately below the Rest House and the old crescent shaped beach that stretched away in the distance was still there but not as beautiful a sight as described by Leonard Woolf when he was Assistant Government Agent in the early 1900s. Although we could not see the new Chinese harbour we could clearly witness the tall secretive cranes, which protruded into the sky – not visible to any passer-by because of the high protection bunds along the surrounding roads. Our attempt to see the harbour was curtailed by a roadblock and a sentry. I introduced Sir Christopher to Mr B Cassim an old Malay lighthouse keeper. He told us how his family had survived the 2004 tsunami because they had left Hambantota earlier that morning. He said, life had never been quite the same and gave us photographs of the destitution and what they had witnessed the next day when they returned. It was horrifying. Our journey back to Tangalle was mostly silent. We had a lot to think about. The horrific destruction of Hambantota will take a long time to forget – as will the price this country has paid to end the civil war. The significant influence that China will have in the country – both politically and economically – is hard to ignore.

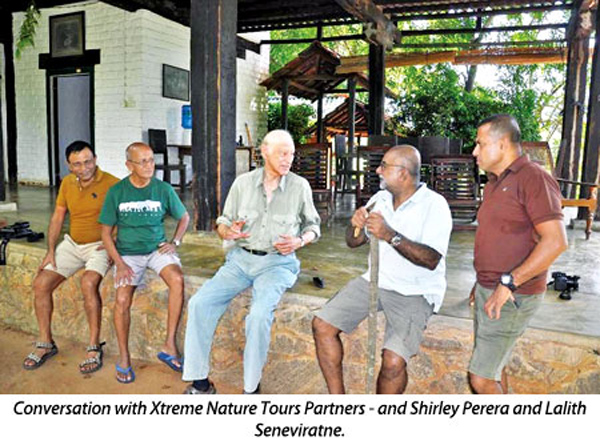

Although it is less than a 100 miles from Tangalle to Kumana as the crow flies, it took us almost five and a half hours to make the journey to the Kumana National Park gates. The road followed the winding devious elephant path around the Moneragala hills – making the journey almost three times as long. We were met by Christopher and Marlon Perera (no relation) – major shareholders of Xtreme Nature Tours. We were also welcomed by the Park Warden Sisisra Ratnayaka, and Gaminie Samarakoon, ex Assistant Director of the region. Through his initiative he had managed to increase the size of the Park by a third during his time in the region.

Formerly known as Yala East National Park, Kumana is located at the southernmost corner of the Eastern Province. Kumana is undoubtedly the most picturesque area of the dry zone coastline of the Island. The Park is physically separated from the more famous Yala National Park by the gently flowing waters of Kumbukkan Oya (river). The very name Kumana conjures visions of our abundant wealth of avifauna in all its plumed splendour. A natural highlight of the Park is Kuman Villu, a 500-acre mangrove swamp lake sustained by the river through a half mile long narrow channel. These mangrove swamps are a destination of choice for migratory birds.

Among regular visitors who nest and breed are spotted billed pelican, painted stork, spoonbill, white ibis, open billed stork, eastern purple heron, eastern grey heron, eastern large egret, median egret, little egret, pond heron, night heron, chestnut bittern, Indian darter, Indian shag, little cormorant, complemented by resident birds Indian waterhen, water cock, purple coot, pheasant-tailed jacana, black-winged stilt, whistling teal, and the little grebe. In the Villu grow kirala trees interspersed with bushes of karang and hambu. The Villu lies amidst abundant wildlife filled planes and jungles, archaeologically rich rock outcrops of fantastic shapes with their many habitable drip-ledged caves and inscriptions dating to pre-Christian times, and miles of unexplored golden beaches. The successive saltwater lagoons along the coast,each surrounded by extensive plains give the impression that this indeed is the mythical Garden of Eden. The lagoons attract numerous sandpipers, plovers, ducks, and waders during the North-East Monsoon. Animals found in adjacent Yala are also found in Kumana.

We piled our bags into the two camp jeeps and made a three hour game drive to Ada Kumbuka Camp 2 – on the banks of the Kumbukkan Oya (river) – the last remaining great river of Lanka still untouched by man and undammed. The campsite is named after the giant slanted Kumbuk trees draping over the riverbank at that spot. Rumour has it that the largest recorded blue sapphire in the world (1,500 carats) was found in the river some years ago. We saw plenty of bird life, spotted deer, three elephants, wild boar, peacock, etc. – but no leopard sighting despite several alarm calls and the putrid smell of a buffalo calf carcass which the Pereras had seen the day before killed by a leopard. We felt that he was around – but out of sight. Leopards do not stray too far from their killed prey for several days.

Arriving at the camp we were met by the well-known former Deputy Director of Wildlife Shirley Perera (Christopher Perera’s father). Sir Christopher had not met Shirley since 1991 when he spent two months in Sri Lanka researching and writing his book The Man-Eater of Punanai They had a lot to talk about, especially, about the late Nihal Fernando the well known photographer, author, and owner of Studio Times. It had been raining a lot in the Park. The roads we travelled were muddy and sometimes impassable. It also made tent camping damp and difficult but the Pereras were very professional and made things as comfortable for us as they possibly could. There were four spacious tents well covered from the rain as well as sheet covers, torches, ground sheets, and teapoys, in which we put our possessions and clothes. The tents were under the canopy of a sprawling Mee tree above which grey languor and macaque monkeys enjoyed pelting our camp with Mee tree fruit and seeds. We were surrounded by constant gunshot sounds as the heavy fruit landed on our protective camp covering. It was ceaseless.

(To be continued)

In the wilds of Kumana – PART TWO: A Diagonal Journey across Sri Lanka with Sir Christopher Ondaatje – Text and pix by Lalith Seneviratne

Sir Christopher Ondaatje and Lady Valda Ondaatje

Continued from last week

It was overcast and wet but we woke up at 5 am, had coffee and tea, and drove into the Kumana forest to search for game. A sloth bear put on a good performance for us, digging underneath a log at the side of the Park track until we disturbed it with our photography. It was a beautiful beast that attended to its toilet a few feet off the road until we moved on. The Ceylon Sloth Bear (Melursus ursinus

inornatus) is a sub species confined to Sri Lanka and the only bear species found on the Island. Its range is confined to the receding parts of the lowlands of the Dry Zone. It appears to be the least carnivorous of the carnivora here. Its diet consists of mainly insects and larvae, wild honey and bee grubs, with fruit, flowers, bulbs, and roots according to the season of the year. In the wet season when the ground is soft it digs out termites and their larvae from the white ant hills that abound in the forest jungles it inhabits, or else it searches for beetles, grubs and other insects and larvae beneath rotting logs and boulders. In the dry season it lives more upon fruit, berries, flowers and honey. The principal jungle fruit on which it feeds are Palu, Mora, Kon, Timbiri, and Damba and at times the strong smelling flowers of the Mee tree. It sometimes feeds off the carcass of a dead animal. To man, the trouble with the bear is that both its eyesight and its hearing are not too acute and his nerves are tenuous. It follows, therefore, that when he is engrossed in his business of finding food he might suddenly and unexpectedly find himself in close proximity to a human. He loses his head and panics. He charges straight sweeping the man to the ground with the force of his rush or with a blow of his paw, and then mauls him with a bite or two (generally to the face or head) or another sweep of his destructive claws. He then usually retreats into the jungle and to safety. Had the human appeared from windward, or had the bear some warning, it would probably avoid any confrontation. The fact remains that the bear is more feared by jungle villagers than any other animal except perhaps a rogue elephant. Generally, bears are seen alone, in pairs, or in family parties of a female and her cubs. Sometimes, a female bear in season, may be followed by two or three quarrelsome males. Most bears usually remain in a given tract or range in the forest unless driven to water during a severe drought. Bears seem unable to sustain thirst.

Elephants and Birds

A brown fish owl, the first I had seen for some time, exposed itself to us. More spotted deer and a lonely elephant in the plain – a black animal that Shirley Perera explained to us was the lowest of the three elephant castes. I did not know that elephants had a caste system. The senior caste elephants are lighter coloured and have five toes rather than the four – together with obvious mottling shades. Shirley Perera’s knowledge of wildlife – particularly, elephants and birds – is boundless.

Shirley Perera joined the Wildlife Department in 1956 when he was twenty-one years, bypassing attractive jobs in Colombo, which were not that difficult to find for a young man with an English education. The Head of the Department at that time was the Cambridge educated scholar C. W. Nicholas who encouraged his staff to question and learn while instilling the discipline needed for a ranger’s job. Shirley Perera came from a railway family but jungles were his fascination. He went where his father went with the railways and attended eight schools in different parts of the country. He majored in English and Latin in senior school. His wildlife training was in Yala and there he developed his love for Kumana where he later served as Ranger from 1966 to 1972, as Warden from 1979 to 1985, and later as Assistant Director Eastern Region. He finally served as the second highest officer of the Department (Deputy Director), based in Colombo from 1987 to 1990. Long years in Kumana have taught Perera to know every nook and corner of the area like the back of his hand – along with its legends and lore.

Traditional cuisine

We had stringhoppers – a traditional cuisine, originating in Sri Lanka, and several curries for lunch. Christopher Perera had somehow found a cook with a rare culinary talent. We rested until 3 pm when we set off for our afternoon game drive. Another sloth bear, kingfishers, flying Malabar pied hornbills. We stopped to climb to the millennia old Bowatta Gala – a large turtleback rock outcrop south of the Kumana Wewa – difficult terrain – but fascinating. The turtleback contains several Gal Kem (rock waterholes), caves with inscriptions, remains of a small dagoba and scattered brick and stone works, and is a good habitat for the sloth bear. An engraving of a fish (symbol of a local chieftain) is seen in one of the caves. The view from atop the rock is outstanding with a commanding view of the Kumana Wewa and surrounding jungles. Still no leopard sighting – but again the stinking persists of the putrefied buffalo carcass.

Both, Sir Christopher and I have been to Yala Game Reserve many times, and we have often heard stories of trackers being able to speak to elephants – sometimes with disastrous consequences. The stories were scarcely believable – but on the next morning game drive we witnessed something extraordinary. A large bull elephant blocked our jeep just as the sun was coming up. It was impossible for us to pass him. However, Shirley Perera stood up in the back of the jeep and spoke calmly and with authority to the elephant and reasoned with him. We were speechless. He continued to talk with the bull elephant literally inches from the front of our jeep. “Good morning. How are you? You are a fine fellow. Why are you blocking our way? Don’t you see that we want to go along this road? Be a good fellow. Why don’t you step backwards and let us pass?” Perera continued to talk for probably about five minutes and then we witnessed – the first time I had ever seen anything like it – the elephant taking, first, one step backwards then two steps, then three and four for about fifteen yards. Then, continuing to back up, the elephant backed into the jungle on the side of the road. It was an amazing sight. Our jeep slowly moved forward, with Shirley Perera turning to the elephant and saying, “Thank you very much. You are a good fellow. Have a good day”

We worked hard on our game drives. The roads were muddy and it was tough slogging. We got some good photographic shots of a striped necked mongoose digging for food along the soft muddy road. It continued to be overcast – but in the late morning we saw a large male leopard moving briskly away from us seemingly in a hurry. We sensed that he knew something that we didn’t – and very soon the heavens opened and there was a downpour. We returned to camp – jubilant that we had seen our first leopard.

Plagued by rain

Rain! We were plagued by rain, but consoled ourselves with the excellent food given us by Christopher Perera’s cook: fish curry, coconut sambol, roti, papadams, basmati rice. There were lots to eat – and usually followed by delicious buffalo curd and kitul pani.

These rains in the middle of October were persistent. We wondered if they were the start of the North East monsoon. If they were they could continue for three months. Alternatively, they might just be a passing low pressure system from the South-West. It didn’t matter. We were doing what we loved best – camping and looking for wildlife in our favourite nature reserves. Painted storks huddled in prayer – looking down silently in shallow lagoons of water in the sodden plains. Herds of spotted deer – stags leading the rush across and in front of our jeep. Another brown fish owl, and an oriental scops owl – which I hadn’t seen before. Later on, our hosts alerted us to the distinct call of the oriental scops owl marking its territory on the banks of the river – “buk tak tarak” Only darkness forced us to stop our game drives after which we returned to camp for more superb food and tall wildlife tales. “This is the best life in the world” Sir Christopher said. He had come a long way – in fact from Nova Scotia and London – and he wasn’t disappointed.

Fourth and last day

On our fourth and last day in Kumana – on our final game drive – we luckily glimpsed an old territorial leopard resting in a glade on the side of the road. He was old – probably about 12 years – and was territorial. Some good photography. Sir Christopher, I know, was having trouble focusing with his new Lumix 300 camera. It was a new lighter model and had a lengthy 600mm range. Unfortunately, if a branch or twig stretched across in front of the animal or bird the result was that the photographic quarry would remain slightly out of focus. I somehow tinkered with his camera settings although I did not have access to the manual, so that he could pinpoint his focus – to correct the photographic result. I don’t know how I did it – but I adjusted the focus on both the automatic and the program modes. We both decided to adjust the camera to an “Intelligent Auto” setting for general wildlife photography. This worked quite well. But we still had a long way to go.

Strangely, on the final morning when we left Kumana at 5:30 am it was a bright sunny day. The birds seemed to welcome the change in the weather and we saw pied kingfishers, adjutant storks, crested hawk eagles, serpent eagles, and a black-necked stork. We headed to the Park exit with our bags, said goodbye to the Pereras, and started our long journey to the Gal Oya Lodge at Rathugala, in the foothills of the Mahakanda Range.

The Gal Oya Lodge is a relatively new wildlife destination – owned and operated by Tim Edwards – son of Jim Edwards the former owner of Tiger Tops in Nepal. Sir Christopher and Valda had not seen the Edwards for 23 years. It was a surprise for them. We arrived about 1:30 pm and were met by Brent Barber – a Rhodesian who had been working at the Lodge for less than a year. The Gal Oya Lodge is a small tasteful lodge designed by Architect Cecil Balmond.

The Lodge -a unique out of the way boutique hotel – is situated near an ancient abode of the Vedda people. In these mountains, scattered with caves, lived hunter-gatherers who have now moved down to lower elevations and integrated into the agricultural society. However, there still retain some of their customs and traces of their language. In this area is a rock called Danigala (2,565 ft.) that contains one of the largest and the last Vedda inhabited caves, called, Pattiyagalge.

The Gal Oya Lodge

The foothills of the Range are covered in acres and acres of aralu, bulu, and nellie medicinal forests – a beautiful and flourishing orchard – a veritable ‘jungle pharmacy’ believed to have been planted during the glorified time of early Lanka kings. This whole area encompasses the medicinal forests called, Bulupitiya Talawa. The area is also the home of the rare and endemic painted partridge. The Gal Oya Lodge is about a half hour drive from the Gal Oya Reservoir known as the Senanayake Samudraya, the largest freshwater body (25,900 hectares) and a very special reservoir in Sri Lanka. The Lodge itself is an amazingly brave development and well worth visiting. It is comfortable, and different from any of the other lodges that I have seen in the country. There are original bird walks, journeys to archaeological sites – particularly, to Rajagala where it is believed that relics of Arahat Mahinda who brought Buddhism to the Island are enshrined – and extraordinary boat safaris on the Senanayake Samudraya. There we searched for elephants, travelling through the dead carcasses of century old trees which provided perfect roosting places for terns, egrets, fish eagles, cormorants, and herons. The Gal Oya Reservoir was the first large reservoir and irrigation project undertaken in independent Ceylon. Gal Oya has almost become a household word. It is symbolic of the New Lanka. “May it attain fulfilment speedily and herald the progress of our march towards self-sufficiency” – so said Rt. Hon D. S. Senanayake, Father of the Nation and the first Prime Minister of Ceylon after it was granted Independence in 1947. It is in his honour that it is named Senanayake Samudra or Sea of Senanayake. The reservoir is the heart of the nearly 100 square mile Gal Oya National Park.

At the edge of the reservoir one has to search for the elephants who come down to the water to drink and bathe. If one is lucky one will see them swimming between the islands in the reservoir, with only their trunks protruding out of the water, like periscopes, a marvellous and a rare sight. We only stayed three nights at Gal Oya – resting from our Kumana camping experience. I had to go to Namal Oya about 15 miles away because there was no telephone coverage at the Lodge area. Sir Christopher however spent the time writing, or going for long walks with Lady Ondaatje along the adjoining paddy field bunds. One morning he and I spent four hours in a boat exploring the Gal Oya reservoir – which is enormous. We took many photographs of birds roosting on the tree skeletons -fish eagles, cormorants, egrets, white-bellied sea eagles. We also got quite close to a pair of elephants enjoying the lush reservoir grass. Later in the day, we were told by Belinda Edwards that she had videoed the two elephants swimming across between the islands. Interestingly, the roofing of the Gal Oya Lodge is entirely of iluk grass, an indigenous thin tall grass slowly being overtaken by invasive grass. Traditionally, this grass was a thatching material but now, because of its scarcity and the labour needed to thatch, this roofing is seldom seen.

From Gal Oya we drove for five hours to the Ulagalla Walawwa – originally owned by Anula Kumarihami hailing from an old Sinhala chieftain family. She married Kiribanda Panabokke who was from Kandy. Wallawwas are manor houses that date back from Portuguese and Dutch times. The rains continued to follow us all the way up to Ulagalla – just over 15 miles from Anuradhapura. The Walawwa was actually built in 1915 but during the worst part of the civil war in 1985 Anuradhapura became a military town and it was taken over by the army as their headquarters in this strategically important part of the country. It is the gateway to the North. Ulagalla Walawwa was bought by the current owners Uga Escapes in 2007. They have done a masterful job renovating the old building. The staff was very pleasant and welcoming, and the landscaping of the sprawling grounds provided us with a comfortable hideaway before our next ‘extreme experience’ in Wilpattu.

We spent two nights at the Ulgalla Walawwa resting and writing. Sir Christopher had a lot to talk about. In between work sessions we experienced the delightful cuisine of the Walawwa, cycled around the property, used the well outfitted gym, sauna, and made visits to the spa with their Balinese therapist. It was a wonderful experience and Sir Christopher talked fondly about his friends Sam Elapata Jr and Siran Deraniyagala whose Walawwas in the Ratnapura district he visited in the 1940s and early 1990s.

(To be continued)

Victor Melder

Sri Lanka Library

A Diagonal Journey across Sri Lanka with Sir Christopher Ondaatje: ‘My legacy is my family’ – PART three: Text and pix by Lalith Seneviratne

Lady Valda Ondaatje and Sir Christopher Ondaatje…Breakfast Outside Wilpattu National Park

Continued from last week

The only side trip Sir Christopher and I made was to Anuradhapura where we found that long after the end of our prolonged civil war the town still remains very much a major military base. Sir Christopher bought a black safari jacket designed for the Special Forces as he said his damp clothes were beginning to smell. He also needed some glue for his safari journal which he kept religiously, every day. We drove the short distance to Kaludiya Pokuna – where we were away from the crowds and where enlightened bhikkhus wentto bathe. This is somewhat near Mihintale – the cradle of Buddhism in Sri Lanka and still a peacefully beautiful spot – not ruined by crowds of invasive tourists. The old dagoba, several expressive monkeys, and a single bhikkhu made our visit to the pond a quietly expressive happening.

Back at the Walawwa the rain continued but it did not spoil the good time we had there. It is one of my favourite places on the Island. We were anxious to resume our safari with Xtreme Nature Tours and the Pereras who had driven up to Wilpattu. We expected the worst – and the worst happened. Before we even got to Wilpattu we were told that the causeway at Eluwankulama had been flooded and that camping was impossible. So instead, the Pereras rented a small bungalow ‘Anawila’ on the outskirts of the main entrance to Wilpattu at Hunuwilagama – perhaps 15 minutes from the Park gates. The weather did not prevent us having a full wildlife experience in Wilpattu, and the Pereras went out of their way to make this happen. On the way to Wilpattu we stopped at the Polonnaruwa Rest House (now called Lake View Hotel) and owned by Galle Face Hotel, Colombo. Sir Christopher was last here in the early 1990s on his final stop before making his final journey to Punanai – then still in Tamil Tiger territory – for his book about the notorious man-eater.

At Hunuwilagama we were met again by Christopher, and Marlon Perera, Shirley Perera (still determined to continue his safari career), and Indika Gunasekera – the third partner of Xtreme Nature Tours. They served us another delicious rice and curry meal. We had heard that the day before there had been an unfortunate event where a spotted deer had been caught in a snare. The caretaker of the bungalow turned out to be one of the suspects. It was a nasty situation that Shirley Perera and the owner of the bungalow tried to sort out. Rules against trapping and snaring of protected animals are very strict.

Wilpattu game drive

The afternoon was cool when we set out on our first Wilpattu game drive. There was the ever-present threat of rain but we were prepared for the worst. We had got a couple of photographs of a pair of blue tailed bee-eaters silhouetted against the dark sky when there was another heavy downpour and an uncomfortable drop in temperature. Most of us shielded our bodies from the rain where we were seated, above the driving cab section. The only confession from Sir Christopher was that below a certain degree in the temperature his body simply didn’t work! It was a relief to get back to our small rented bungalow. We got out of our wet clothes and showered. It was good to be warm again in the The Anawila bungalow – a welcome dry retreat for us. Coconut arrack followed by chicken curry and roti also helped us dry out.

Wilpattu, literally meaning the Land of Lakes is about 130,000 hectares or 500 sq miles, the largest National Park in Sri Lanka. The Mahavamsa records that in 543 BC Prince Wijaya landed at Kudiramalai Point (Horsehead Mountain or Horse Point) on the present northwest border of the Park. He then married Kuveni and founded the Sinhala race. It is thought that the plains of Pomparippu were the rice bowl of Sri Lankan civilisation. Wilpattu was a hunting reserve for the British in the early 1890s, and the 500 square miles were declared a sanctuary in 1905. With the intervention of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka in the 1930s three important decisions were made: The first, the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance was enacted in 1937, and has been in effect since 1938 with an amendment in 2009. It led to the formation of the Wildlife Conservation Department and the conferring of National Park status to Wilpattu, in February 1938. Within the Park there are numerous sites of archaeological interest. Natural saucer-like lakes, and many breached irrigation tanks and channels indicated the opulence of the early Kingdoms. The Park is a unique landscape composed of attractive high forest with tenacious liana and thorny scrub interrupted fairly regularly by verdant plains and soothing sand-rimmed basins of water known as villus. There prevails an infectious calm and tranquil atmosphere for all who enter its boundaries. There are very few dull moments as you scan the edges of the unique villus. You have to be alert. Flocks of whistling teal, herds of deer, wild hare, open-billed storks, cormorants, snakebirds, tortoises, and crocodiles are in abundance. Sir David Attenborough once referred to Wilpattu as “the best place on earth to see the leopard.”.

Long three and a half hour game drives. We dressed at 4:30am and were ready to go. We tried hard to get to the Park gates when they opened at 6 am – so, first we had breakfast. The game drive itself was a slow, rough drive: we were able to view a brown fish owl, a chestnut headed bee-eater, and an expressive serpent eagle. We worked hard driving the inner tracts of Wilpattu and found our first Wilpattu leopard at noon – very near the Park gate – a beautiful healthy male, lounging in the red soil, attending to his toilet, and giving us some good photographic opportunities. This was one of our best mornings. No rain. We were exalted. Palu and Weera trees lined the Wilpattu jungle road – a red dirt track. But there was always the threat of rain. Eventually it poured – but we were not disheartened. The high humidity continued and it was strangely cool. There were occasional passing showers. We photographed stone plovers, sand plovers, and sambhur.

Irreplaceable experience

The long rough game drives were tiring – but this is what it is all about. An irreplaceable experience. We are all bonding together well. The afternoon game drive was followed by some strong arrack and Black Label scotch. We needed it – beforesprucing up for another camp dinner. Stringhoppers and pork curry followed by some delicious papaya from an adjoining chena – which was laden with fruit. Time for more stories and debate. This time the mysterious “Devil-bird” and superstitions attached to the piercing cries and convulsive screams of this night bird called “Ulama” in Sinhala, meaning “the screecher”. It is believed, the cry of this bird, very similar to the cry of a strangled child, is an omen of death. The debate continues today as to whether it is the forest eagle owl or the crested hawk eagle. Sir Christopher thinks it is the latter. The true identity of the bird is still one of the mysteries of the Ceylon jungles.

There is always something exciting about the Pereras’ ‘Xtreme Nature Tours’. Breakfast a little late at 8 am before our last, long, late Wilpattu game drive. Nothing much happened before noon – sambhur and fawn, and the opportunity to take some photos of an empty Wilpattu game track. The Park has a different character than any other game park in the country. It was a Monday and there was an oppressive atmosphere that warned us of another heavy downpour. It happened – and we huddled under a waterproof tarpaulin to protect ourselves. Moments later we saw a single female leopard across the jungle track between us and another jeep. She seemed to be in a hurry and looked for a tree or some cover. Then the rain hit her and she scurried away under the cover of a large Palu tree. There followed a short period when we were both miserable, looking at each other – she huddled below her Palu tree and we, cowering under our tarpaulin. But then, probably in disgust, she shook the water off her slender body and disappeared into the jungle. We did not see her again.

Pools of muddy water in the jungle track made driving difficult. Christopher Perera and Marlon Perera took turns driving – and they handled the difficult task well. An unconcerned shikra blocked our path in one of the brown muddy pools while we photographed her. It was an unusual place for her to be resting. This last game drive lasted an incredible seven hours. We knew it was our last day. We had a late lunch: country rice, ladies’ fingers, and fried fish.

Kasyapa’s rock kingdom

I developed a bad cold. This was not surprising as I had been sitting at the back of the jeep in wet clothes for the best part of four hours. However, I was determined to continue my interview with Sir Christopher. Getting wet is one of the hazards of camping in Sri Lanka in the mid-October season – but I wouldn’t miss it for the world. We swapped wild stories … Sir Christopher talking about East Africa and the Serengeti Plains, and Shirley Perera talking about more of his personal experiences working in the Wildlife Department.

After Wilpattu Sir Christopher and his wife Valda spent three days in Sigiriya before meeting up with us again in Colombo. He made some unusual observations of Kasyapa’s rock kingdom. He said that the north eastern side of the Rock – which is on the opposite side of the present Rest House – shows a much clearer picture of the crouching lion with its full head and flowing mane. The throat entrance with the lion paws remain in the same place – but the seldom seen ‘other side’ of the Lion Rock gives a much clearer reason why the Rock has its name. Hesays, it is a sight worth seeing. I remember seeing the old black and white British historical film on Sigiriya and vaguely recall seeing the Sigiriya Rock as Sir Christopher described it. He told me that he had some heated arguments with the late Nihal Fernando about the Rock – who was not persuaded. Another observation Sir Christopher made is that he believed (almost certainly true) that a Buddhist monastery existed on the Sigiriya Rock before Kasyapa took it over for his palace fortress. Kasyapa then encouraged the Buddhist priests to move to the mighty Pidurangala north west of the Lion Rock – which they did and continued for many years after the 5th Century. He has photographed the Pidurangala Rock from the west side, many times – and towards midday when the sun shines on the large expanse of the grey rock he said, it appears as if a giant drip-ledge has been carved around Pidurangala to collect water at the low southern point where the water would have accumulated. It seems impossible that such a mighty undertaking could have been achieved but if you are a dreamer like he is, anything might have been possible. Certainly King Kasyapa’s ambition seemed boundless for the twenty-two years he ruled the Island.

I met Sir Christopher only twice more in Colombo. We had dinner at my house with the professionals turned naturalists, Stefan D’Silva and Raminal Samarasinghe. They traded wild theories at night – which had to be cut short so that we could have our dinner cooked by Ayanthie: baked crab, chicken curry, baked fish, dhal, stuffed capsicum, maldive fish sambol, katte sambol, bean curry, and organic yellow rice. We finished with watalappan, and chocolate and caramel fudge. After a stirring evening we all decided to get together again to promote the protection of rock and cave art in Sri Lanka. Some of these extraordinary, inaccessible places have been photographed and published in Stefan D’Silva’s latest book “Isle of Mystique – Isle of Legend.”

Time spent with Sir Christopher was for me a ‘dream come true’. I will always think of him as perhaps the greatest Global Ceylonese. I learned from him. After being a highly successful entrepreneur he became a respected author. What Sir Christopher has taught us is the importance of being able to reinvent oneself. He has taught us not to expect anything … just to be honourable. If countries, or people, or institutions are good to you – then you have to be generous in return. It may not be expected. You just have to do it. This is a timely message that will put many of us in Sri Lanka to shame. Today, we seem more embroiled in a question of national identity.

Finally, Sir Christopher’s parting remarks to me will forever be etched in my mind:”My legacy is my family. If I am going to be remembered I want to be remembered for my family. Nothing else matters. If I have failed with them – then I have failed in life – and that is a dangerous option.”

I cannot think of finer words from a finer man.

About the author:

Lalith Seneviratne is a Chartered Engineer. For his contribution to conservation and sustainable development he was elected an Ashoka Fellow and a Lemelson Fellow. He was instrumental in redeeming Kumana National Park in 2002 and was made an Honorary Director in the Department of Wildlife Conservation.

Concluded.