A tribute to vajira-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

The female dancer’s form figures prominently in Sinhalese art and sculpture. Among the ruins of the Lankatilake Viharaya in Polonnaruwa is a series of carvings of dwarves, beasts, and performers. They surround a decapitated image of a standing Buddha, secular figures dotting a sacred space. Similar figures of dancing women adorn the entrance at the Varaka Valandu Viharaya in Ridigama, adjoining the Ridi Vihare. Offering a contrast with carvings of men sporting swords and spears, they entrance the eye immediately.

A motif of medieval Sinhalese art, these were influenced by hordes of dancers that adorned the walls of South Indian temples. They attest to the role that Sinhala society gave women, a role that diminished with time, so much so that by the 20th century, Sinhalese women had been banned from wearing the ves thattuwa. Held back for long, many of these women now began to rebel. They would soon pave the way for the transformation of an art.

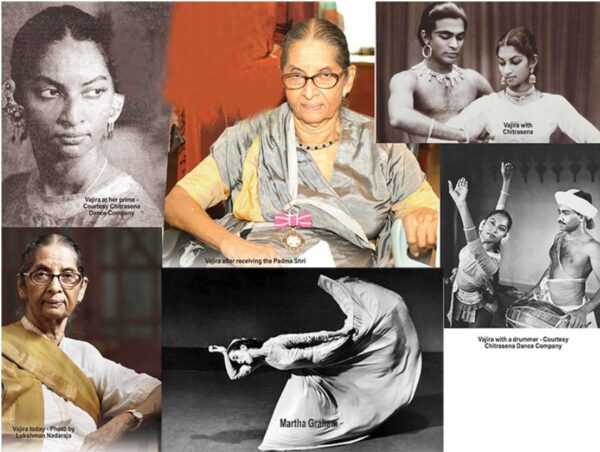

In January 2020 the government of India chose to award the Padma Shri to two Sri Lankan women. This was done in recognition not just of their contribution to their fields, but also their efforts at strengthening ties between the two countries. A few weeks ago, in the midst of a raging pandemic, these awards were finally conferred on their recipients.

One of them, Professor Indra Dissanayake, had passed away in 2019. Her daughter received the honour in her name in India. The other, Vajira Chitrasena, remains very much alive, and as active. She received her award at a ceremony at the Indian High Commission in Colombo. Modest as it may have been, the conferment seals her place in the country, situating her in its cultural landscape as one of our finest exponents of dance.

Vajira Chitrasena was far from the first woman to take up traditional dance in Sri Lanka. But she was the first to turn it into a full time, lifelong profession, absorbing the wellsprings of its past, transcending gender and class barriers, and taking it to the young. Dancing did not really come to her; it was the other way around. Immersing herself in the art, she entered it at a time when the medium had been, and was being, transformed the world over: by 1921, the year her husband was born, Isadora Duncan and Ruth St Denis had pioneered and laid the foundation for the modernisation of the medium. Their project would be continued by Martha Graham, for whom Vajira would perform decades later.

In Sri Lanka traditional dance had long turned away from its ritualistic past, moving into the stage and later the school and the university. Standing in the midst of these developments, Vajira Chitrasena found herself questioning and reshaping tradition. It was a role for which history had ordained her, a role she threw herself into only too willingly.

In dance as in other art forms, the balance between tradition and modernity is hard, if not impossible, to maintain. Associated initially with an agrarian society, traditional dance in Sri Lanka evolved into an object of secular performance. Under colonial rule, the patronage of officials, indeed even of governors themselves, helped free it from the stranglehold of the past, giving it a new lease of life that would later enable what Susan Reed in her account of dance in Sri Lanka calls the bureaucratisation of the arts. This is a phenomenon that Sarath Amunugama explores in his work on the kohomba kankariya as well.

Yet this did not entail a complete break from the past: then as now, in Sri Lanka as in India, dancing calls for the revival of conventions: the namaskaraya, the adherence to Buddhist tenets, and the contemplation of mystical beauty. It was in such a twilight world that Vajira Chitrasena and her colleagues found themselves in. Faced with the task of salvaging a dying art, they breathed new life to it by learning it, preserving it, and reforming it.

Though neither Vajira nor her husband belonged to the colonial elite, it was the colonial elite who began approaching traditional art forms with a zest and vigour that determined their trajectory after independence. Bringing together patrons, teachers, students, and scholars of dance, the elite forged friendships with tutors and performers, often becoming their students and sometimes becoming teachers themselves.

Though neither Vajira nor her husband belonged to the colonial elite, it was the colonial elite who began approaching traditional art forms with a zest and vigour that determined their trajectory after independence. Bringing together patrons, teachers, students, and scholars of dance, the elite forged friendships with tutors and performers, often becoming their students and sometimes becoming teachers themselves.

Newton Gunasinghe has observed how British officials found it expedient to patronise feudal elites, after a series of rebellions that threatened to bring down the colonial order. Yet even before this, such officials had patronised cultural practices that had once been the preserve of those elites. It was through this tenuous relationship between colonialism and cultural revival that Westernised low country elites moved away from conventional careers, like law and medicine, into the arduous task of reviving the past.

At first running into opposition from their paterfamilias, the scions of the elite eventually found their calling. “[I]n spite of their disappointment at my smashing their hopes of a brilliant legal and political career,” Charles Jacob Peiris, later to be known as Devar Surya Sena, wrote in his recollection of his parents’ reaction to a concert he had organised at the Royal College Hall in 1929, “they were proud of me that night.”

If the sons had to incur the wrath of their fathers, the daughters had to pay the bigger price. Yet, as with the sons, the daughters too possessed an agency that emboldened them to not just dance, but participate in rituals that had been restricted to males.

Both Miriam Pieris and Chandralekha Perera displeased traditional society when they donned the ves thattuwa, the sacred headdress that had for centuries been reserved for men. But for every critic, there were those who welcomed such developments, considering them essential to the flowering of the arts; none less than Martin Wickramasinghe, to give one example, viewed Chandralekha’s act positively, and commended her.

These developments sparked off a pivotal cultural renaissance across the country. Although up country women remain debarred from those developments, there is no doubt that the shattering of taboos in the low country helped keep the art of the dance alive, for tutors, students, and scholars. As Mirak Raheem has written in a piece to Groundviews, we are yet to appreciate the role female dancers of the early 20th century played in all this.

Vajira Chitrasena’s contribution went beyond that of the daughters of the colonial elite who dared to dance. While it would be wrong to consider their interest as a passing fad, a quirk, these women did not turn dance into a lifelong profession. Vajira did not just commit herself to the medium in a way they had not, she made it her goal to teach and reinterpret it, in line with methods and practices she developed for the Chitrasena Kala Ayathanaya.

As Mirak Raheem has pointed out in his tribute to her, she drew from her limited exposure to dance forms like classical ballet to design a curriculum that broke down the medium to “a series of exercises… that could be used to train dancers.” In doing so, she conceived some highly original works, including a set of children’s ballets, or lama mudra natya, a genre she pioneered in 1952 with Kumudini. Along the way she crisscrossed several roles, from dancer to choreographer to tutor, becoming more than just a performer.

As the head of the Chitrasena Dance Company, Vajira enjoys a reputation that history has not accorded to most other women of her standing. Perhaps her greatest contribution in this regard has been her ability to adapt masculine forms of dance to feminine sequences. She has been able to do this without radically altering their essence; that has arguably been felt the most in the realm of Kandyan dance, which caters to masculine (“tandava“) rather than feminine (“lasya“) moods. The lasya has been described by Marianne Nürnberger as a feminine form of up country dance. It was in productions like Nala Damayanthi that Vajira mastered this form; it epitomised a radical transformation of the art.

Sudesh Mantillake in an essay on the subject (“Masculinity in Kandyan Dance”) suggests that by treating them as impure, traditional artistes kept women away from udarata natum. That is why Algama Kiriganitha, who taught Chandralekha, taught her very little, since she was a woman. This is not to say that the gurunannses kept their knowledge back from those who came to learn from them, only that they taught them under strictures and conditions which revealed their reluctance to impart their knowledge to females.

That Vajira Chitrasena made her mark in these fields despite all obstructions is a tribute to her mettle and perseverance. Yet would we, as Mirak Raheem suggests in his very excellent essay, be doing her a disservice by just valorising her? Shouldn’t the object of a tribute be, not merely to praise her for transcending gender barriers, but more importantly to examine how she transcended them, and how difficult she found it to transcend them? We eulogise our women for breaking through the glass ceiling, without questioning how high that ceiling was in the first place. A more sober evaluation of Vajira Chitrasena would ask that question. But such an evaluation is yet to come out. One can only hope that it will, soon.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com