At the Feet of Meeriyabedde Upananda Mahanayaka Thera-by Michael Roberts

Source:Thuppahis

Padraig Michael O’Leary Colman, in The Sunday Island on November 27, 2022, where the title reads “The Monk and Me”

On October 13, 2017, we heard the sad news of the death of our very dear friend, the Most Venerable Meeriyabedde Upananda Mahanayaka Thera, the Mahanayaka of Uva Amarapura Nikaya. We knew the Most Venerable Upananda for a long time before we realized how eminent he was. We just knew that he was a special human being. As well as being the High Priest of the Pelgahattene temple, he was also responsible for 56 other temples.

It is difficult to find any information about our friend by Googling, although he was a monk for 80 years and at Pelgahattene for 50 years. He was not one of those celebrity monks who haunts the media, drawing attention to the man rather than the Dhamma. My information about him is mainly based on my personal contact with him over a period of 14 years.

In Ireland they have the term “blow-in”. According to a Hiberno-English dictionary, a blow-in is a newcomer to an area, “someone who has been resident for less than 15 years”. When we settled in Sri Lanka from Ireland in 2002, we felt even more like interlopers than we had done in rural East Cork. In Colombo, we would attract little attention among the hordes of tourists (those were the days, my friend), but when we moved to our house in the mountains, we got strange, possibly hostile, looks as we passed through the nearby villages. We settled in one of the poorest areas of the country. Mine was the only white (or pink) face to be seen for many a mile. Even driving around in a clapped-out old car, we probably seemed rich, strange and privileged.

A Maniyo who knew my wife’s mother stayed with us soon after we moved in to our mountain retreat. She insisted that we must have pirith chanted to bring merit and protection to our household. She introduced us to the Most Venerable Upananda. Our Maniyo friend is a can-do kind of a person and soon arranged for a battalion of monks to come and perform rituals to help the house welcome and nurture us. Our life certainly changed for the better but this is probably not a result of the rituals but because the hamaduru wahansai became a very dear friend and some of the respect accorded to him reflected upon us.

The hostile frowns of the villagers turned to smiles and everyone offered to help us. We were invited to weddings and funerals and functions at the temple and generally felt that we were members of the community. I was given the honour of carrying the Buddha’s relics on my head at one ceremony. On another occasion, I sat beside the local police chief and the speaker of the Sri Lankan parliament presenting prizes to schoolchildren.

When we visited the high priest on his 90th birthday, he showed us a greeting card he had received from the then Head of State, President Mahinda Rajapaksa. The president had also telephoned him to give him his good wishes in person. He had also received a card from the then leader of the opposition and current president, Ranil Wickremesinghe.

The atmosphere around the temple was truly ecumenical. We saw our Muslim neighbours taking their small daughter to the Montessori school at the temple. The Most Venerable Upananda was a great friend of the priests at the Passara Catholic Church and joined them in many community projects. Many Hindu Tamils worked hard to maintain the premises and crops at the temple. We have seen them prostrating themselves at his feet in respect. The Most Venerable’s Tamil driver was tearful with grief at his demise. The Most Reverend won the love of all members of the community because he was upright with no hint of impropriety. He served the whole community, endlessly creating schemes to improve the lives of local people. He helped provide electricity, water and employment, and computer training; he devised schemes for growing mushrooms and producing cooking gas from waste.

The traditional expectation is that the laity provides and serves food to the clergy. We were happy to do this but also, thanks to the Most Venerable Upananda, we rarely had to buy rice or tea because he sent regular supplies to us. Whenever we visited him he insisted that we have breakfast and served us himself. He took particular pleasure in giving me the denture-threatening parippu vade that he knew I liked. “Mr Michael’s favourite!”

The Most Venerable Upananda had a reputation as a healer with special knowledge of traditional remedies. Anyone bitten by a snake went to him for the application of his snake stone to draw out the venom. There was a story, possibly apocryphal, that he was once kidnapped by the Tamil Tigers because of his healing powers and that he was offered a van as thanks for healing a senior cadre. He refused. He was also offered vehicles by mainstream politicians. He refused.

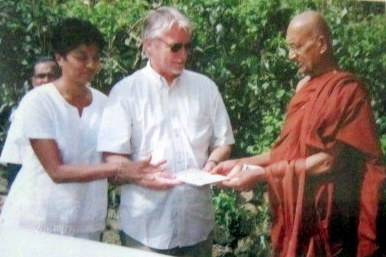

When we decided that we needed a new car, selling the old one was problematic. A potential buyer seemed to be trouble – he moaned about the price and however much we lowered it, we could foresee him coming back in perpetuity to complain about the car’s defects, of which there were many. Our friend Most Venerable Upananda offered to buy the car as it would be helpful to take him to his clinic appointments and various official functions. When she was president of Sri Lanka, Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga offered him a new jeep but he refused. We refused his offer and gave the car to him free of charge.

After we donated our car it became a community project. A local mechanic, without charging, put right many mechanical wrongs and spray-painted the car. He said how he can expect payment when we gave the car as a gift. Many little accoutrements and furbelows have been proudly added. A local builder constructed a new garage free of charge to house the vehicle and the completion of the structure was marked with a little ceremony with songs sung by small schoolchildren.

Our shorthand nickname for the Most Venerable Upananda was “The Don” because we saw him as the benevolent boss at the center of a benign mafia. The French sociologist Marcel Mauss, in his Essai sur le don, published in 1925, described how reciprocal gift-giving builds relationships between groups. The biologist, EO Wilson, coined the wonderful phrase, “the delicate web of reciprocity.” I tell the story of the donation of the car not in order to signal my own virtue. I do not want to engage in what Paul Newman called “noisy philanthropy”. Howard Jacobson coined the phrase “philanthropy – the last refuge of the scoundrel.”

I write not to boast of my own saintliness but to give readers an idea of what an ordinary person can achieve by small acts of direct giving. I challenged ethical philosopher Peter Singer’s idea of “making a difference”. Singer advocates regularly donating a percentage of one’s income to charitable institutions. He recognized that one could not always know how one’s donations were being spent. It seemed to me that this form of delegated compassion makes more of a difference to the giver’s self-esteem than to the welfare of the needy.

Bhikkhu Bodhi edited a small book of essays called Dāna – The Practice of Giving. In his introduction, he writes: “The goal of the path is the destruction of greed, hate and delusion, and the cultivation of generosity directly debilitates greed and hate, while facilitating the pliancy of mind that allows for the eradication of delusion”.

One would not be eradicating delusion if one merely set up a standing order to pay a percentage of one’s salary to an organization without finding out how the money is used. The Argentinian poet Antonio Porchia wrote: “I know what I have given you but I do not know what you have received”.

Andrew Carnegie wrote: “[O]f every thousand dollars spent in so-called charity today, it is probable that nine hundred and fifty dollars is unwisely spent—so spent, indeed, as to produce the very evils which it hopes to mitigate or cure.” Today it is much worse. Humanitarianism has become a billion-dollar industry. NGOs are huge corporate businesses ossified by management and career structures and bureaucracy. NGO workers can build up an image of saintliness as well as developing a lucrative CV.

Richard Titmuss, British social researcher and teacher, published The Gift Relationship in 1970. He compared blood donations in Britain (entirely voluntary) and the US (some bought and sold). Titmuss’ s conclusions concerned the quality of communities where people are encouraged to give to strangers. When blood becomes a commodity, he argued, its quality is corrupted (American blood was four times more likely to infect recipients with hepatitis than was British blood). Titmuss helped preserve the National Blood Service from Thatcherite privatisation.

Lewis Hyde also has examined the concept of the gift. He locates the origin of gift economies in the sharing of food. Many societies have strong prohibitions against turning gifts into trade. Hyde investigates the effect our delusion with the market economy has on our ability to give and receive. In a market economy, wealth is increased by ’saving’. In a gift economy, wealth is decreased by hoarding, for it is circulation within the community that generates increase in connections and strong relationships.

Andrew Carnegie warned successful men who failed to help others that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” Carnegie knew how to make money and he knew how to use it effectively. By the time he died in 1919, he had given away over $350 million ($ 494.2 billion in 2014 money) and he had established charitable organizations that are still active nearly a century after his death. Modern day rich givers like Warren Buffett and Bill Gates have expressed a Carnegie-like wish to divest themselves of their wealth.

Those of us with less wealth than Carnegie and co. can also benefit from giving. We can perhaps benefit more, because we can have the satisfaction of giving to the hand and looking in the eye. Clinging to material goods makes people selfish, struggling to satisfy insatiable desires with transitory pleasures. Dāna is the very practical act of giving; caga is the generous attitude ingrained in the mind by the repeated practice of dāna. The word caga in Pali means giving up, abandonment; the selfish grip one has on one’s possessions is loosened by caga. When we decide to give something of our own to someone else, we simultaneously reduce our attachment to the object; to make a habit of giving can thus gradually weaken the mental factor of craving. Giving is the antidote to cure the illness of egoism and greed.

You do not need to be as rich as Bill Gates is or as well-connected as Bono. You do not have to send money abroad. You do not even have to give money. Awareness is the most important thing. Look around your own area, talk to religious leaders and doctors, talk to your neighbours. They will advise you who is in need. By giving of your heart as well as your money, you can save yourself, make a difference and improve someone else’s life, by giving with wisdom.

It’s a bargain!

We travelled up to Uva from Colombo to pay our respects to our departed friend. We did not stay for the funeral itself on the afternoon of Monday October 16. There was to be a perehara from two o’clock in the afternoon. It was expected that 2,000 bhikkhus would attend. We attended and paid our respects early in the morning. Already, many people, including large parties of schoolchildren were there. Many people were in tears. We will miss him as will many others.