Ceylon’s first university in memory and imagination–By Ernest Macintyre

Source:Island

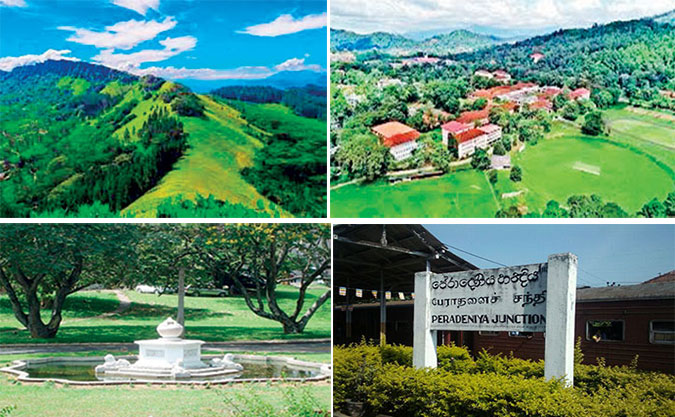

The Mahaweli River, 335 long, the longest river in Lanka, has its beginning in a remote village of Nuwara-Eliya District in the central hills, and ends going into the sea at the Bay of Bengal on the east coast at Trincomalee. As it passes Kandy, the main town of the central province, and goes south about six kilometers, it bends at an elbow to the shape of an arm, to cradle within an expanse of habitation born from nature accommodating Lankan classical and colonial architecture, the residential University of Ceylon, Peradeniya.

From the sandy banks of the river the richly vegetated land slopes gently upward till it reaches the old Galaha Road along which on either side, from the Botanical Gardens junction, north to the ancient Buddhist village of Hindagla ,south, are the buildings designed by architect Shirley D’ Alwis. Sir Ivor Jennings, the first Vice Chancellor took the lead in proposing and constructing the sober and dignified monument in architect Shirley D’Alwis’s honour that is situated at the first roundabout on this central road of the campus with a shallow pond all around it.

The Mahaweli from which we rose up to Galaha road is only one side of the story of nature’s promise. On the other side of Galaha, all along, the land rises further to reach in the distance, the Hantana chain of mountains. Hantana is a chain of seven mountains, surrounded by forest. From the top of the mountains is seen, at the rising of the sun, the University, faraway.

This sunrise in 1955, all was quiet on the campus. There were no students, yet. Ones already at university had four more weeks before term started. But shortly, the many hundreds of new students, those who had just gained entrance would arrive.

So we have a little time to take a walk along Galaha Road Near the village of Hindagala, in the south, where in the mid-1950s the campus ended, was the large Ramanathan Hall. It was the largest of the halls of residence, with three floors and named after Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan who was associated with the movement for independence from Britain for the colony of Ceylon.

Turning back from Ramanathan along Galaha Road ,returning northwards, quite close to Ramanathan was Sangamitta Hall and Hilda Obeyesekere Hall, and also close by, up a hill on the Hantana side was James Peiris Hall. All three for female undergrads.

Sangamitta Hall needs a little more telling; it being the only one with a ancient historical name. Sangamitta was the title or description given to the daughter of King Ashoka of India (about 270 BC). Her name was Ayapali, and was referred to as Sangamitta when she joined the order of Buddhist nuns. Sangamitta and her brother Mahinda were sent by Ashoka their father to spread the Word of The Buddha south across India and ending in Lanka.

James Peiris and Hilda Obeyesekare whom the other two close by halls were named after, were prominent and wealthy social and political figures of the early twentieth century.

To divert now to an undergraduate activity allowable in adulthood in a residential facility of both sexes. The young men called it Kissing Bend. Despite the mischievous manipulation of language enjoyed freely in Peradeniya , Kissing Bend was not a curved part of the physical make up of one of the genders. It was an area of hard asphalt on the ground on Galaha road, where we are now on our walk through the campus.

A location of love’s reluctant closing moments of an evening after Mahaweli meetings. The Kissing Bend, with a big tree covering on one side. Kissing goodnight was just before seven in the evening, the stipulated time for women to be back in their halls, after returning from sessions close together on the banks of the Mahaveli .

young males and females, without the cultural restraint of Pirivena origin, in a university of Western imagination, allowed them freedom of nature. An old English song, ” I Met My Little Bright Eyed Doll, Down By The Riverside”, may have had its Sinhala version, much sung in Peradeniya at the time, ” Mage as deka dilisena bonikka ganga iney sambuna”, emerging from the banks of Peradeniya’s Mahaweli.

Kissing Bend was an important land mark, for as Professor Sarachchandra is reported to have once said to undergraduates: “Peradeniya is not only for passing exams, it is for the passing of young lives, at a time when it is surging.” He did not mean kissing at the bend, yet it relates to human surge and emotion in youth ,and accompanying thought, extends to works of art, which the professor had in mind. It requires imagination to extend to the surge of art, closely pressed bodies and upright, with entangled legs at Kissing Bend. Today it is probably called “imbina wangua“, with the growth of the use of Sinhala.

Moving from alongside Hilda Obeyasekara Hall now in the other direction from Hindagala, the next important structures in those times were the impressive administrative buildings, library and lecture rooms on the left and Arunachalam and Jayatileka halls side by side on the right, named again, after important political figures of the time. From Jayatitilake Hall can be seen the Shirley D’Awis memorial. Honouring the architect who in design, gave to Peradeniya man’s complement to nature. These buildings were given special mention, whatever the intention of the words mean, when the recently departed Queen of Britain and her husband Philip formally declared the University of Ceylon, open.

In the view from Jayatilleka Hall beyond this memorial was the sports grounds and tennis courts. To the right of the sports field was a makeshift accommodation, the Faculty Club. The evening club for the academic staff, who in keeping with their intellectual claims could think better with a drink. This club, apart from private homes was the only place arrack could be had on campus. The two immediate progressions from schooldays to university were ” áll but” freedom with the opposite sex and arrack. The former was easily and discreetly available, the latter prohibited on campus, yet consumed growingly, in the town of Peradeniya and the city of Kandy, bringing back its heartily displayed consumption to the campus.

Further north to the right on Galaha road, beyond Jayatilleka Hall was a narrow asphalt strip branching upwards to the seventh student residence, Marrs Hall, named after an important academic and university official, in its early Colombo University College of London days.

Seven halls of residence somewhat autonomous with an elected student president and a warden. The close social relationships were within each hall, the three meal sittings a convenient regrouping after dispersal into the larger campus body for lectures and tutorials, presided over by people who now, the years have taken away, together with some whom they lectured to, now in their mid eighties. Luudowyk, Passe, Doric de Souza, Sarachchandra, Siri Gunasinghe, H.A.de .S Gunasekara, Vaithianandan, Cuthbert Amarasinghe, Van den Driesen, Sinnappa Arasaratnam, La Brooy, Miss. Mathiaparanam and Basil Mendis. Some from the many.

The ones they educated in the mid fifties will be now in their mid eighties. The lecturers will be remembered for some time more.

Very modern the halls of residence were, with every contemporary facility students could ask for. In fact, Ramanathan Hall may have gone too far , socially inconsiderate, in installing bidets in each toilet. Small porcelain basins fixed to the floor, which spouted water upwards when its tap was opened, to serve the sitter on the bidet. Bidet is an old French word for “pony”, and was associated with Royalty ,the notion that one “rides” or straddles a bidet much like a pony is ridden. Even the Colombo “kultur” students felt more secure in their old manual methods, leaving the French “ponies” as obtrusive ornaments.

To get back to those times, we now move outside to a place that mainly served the campus. The steam train from Colombo had arrived at the small nearby Peradeniya railway station.

That morning the small station was packed with young men and women.They had come from all parts of the country. A good many were from Colombo schools. Amongst names of Sinhala and Tamil origin there were also significant numbers of Fernandos, Silvas and Pereras, resulting from the long Portuguese part of Ceylon history.

Because of free education introduced in 1948, they were well matched in numbers by those from rural Ceylon . South, Central Ceylon and North West below the Jaffna Peninsula which brought into the campus names like Deekiriwewa and Menikdiwela. TheNorth Westerners converged at Polgahawela, and then to Colombo, to change trains for Peradeniya.

The Central Province provided a mixture of Colombo and rural types. Breckenridge , Dhanapala and Senaratne are three we remember, from Trinity College and Premaratne the cricketer from Katugastota. They were not at the station, because they were close enough to Peradeniya.

There were the not so westernised Tamils from Jaffna and the Eastern Province. Not as westernised as the young Tamil men and women of the Colombo schools who had a long history of migration from Jaffna, from 1905, when the first train left Kankesanthurai for the capital city. Singhams, Lingams, Moorthys, Samys amongst others were all there at Peradeniya.

The Ceylon Moors were well spread, Colombo, Kandy, Jaffna and the Eastern Province. We remember Raheem of Royal ,Lafir and Mohamed Mustapha Ibrahim. So, the chatter on the station platform was very mixed. English, mostly from the Colombo schools and the Burghers, Sinhala from the very large area of provinces outside Colombo and Tamil from north and east.

Females, jostled with the males, in a way schoolboys and schoolgirls which they were a few months ago, had not been allowed. They would all be in close residence very soon, after transport from the station in vans. With the exception that females lived in separate halls, morning to evening they were free to be with males, including evening privacy on the banks of the Mahaweli, and at dusk, parting proximities of “Kissing Bend”.

Men together with women hiking up to Hantane in the weekends was another opportunity by which this university helped indicate, conservatively and intelligently, that men and women were meant by nature and civilization to prepare, to mate in proper time.

Significant on the station that morning was race or cultural mixing together. Peradeniya was probably the first social formation in Lanka where Sinhalese and Tamils, Ceylon Moors ,Malays and Burghers in significant numbers would actually live closely and rub shoulders with each other, sharing rooms , dining tables , sport, art , social events and academic discourse.

College House of University College, London University, had a small number of Sinhalese, Tamils and other minorities resident, but that university was largely non-residential. Government departments and commercial firms had both Sinhalese and Tamils and other ethnicities. But no institution in Lanka, before Peradeniya had thousands as one community living, day and night, closely together.

Peradeniya especially opened the opportunity for Sinhalese, Tamil, Moors, Burghers, and Malay youth to explore and conclude that they were one humanity.

Two other identifiable “cultural” groups, outside of ethnicity, that did not initially mix, that is in the 1950’s, were what students called the “O Facs” and the “Kulturs”. The students of the oriental faculties, largely from rural schools who opted for Pali, Sanskrit, Sinhala apart from Economics and History and the urban school students, mainly Colombo, Kandy, Galle and the like who did English. Latin, Greek, Economics, Western Philosophy, History.

It was unfortunate that this unreal social divide very likely created by the cultural snobbery of Colombo school products came into the campus, for it was the “O Facs” who within a year stamped Peradeniya with a cultural creation hallmarking Sri Lankan culture and launching it into South Asian recognition. Maname, a Sinhala creation that stands alongside any dramatic work, anywhere. In time this remnant colonial division imperceptibly wore out.

This day of Peradeniya also saw the last congregation of Burghers, in significant number, benefiting university contribution to the country. Though it is common to hear of Portuguese Burghers and Dutch Burghers of Ceylon, they are of varied European descent like in the composition of the mixed European De Meuron Regiment first employed by the Dutch , then serving the British and finally being disbanded in 1816 in Colombo to become part of the population From that station platform or directly onto the campus that morning, there were names like Ludowyk, Pietresz, Ondaatje, Roosmale- Cocq, Taylor, Hingert, De Zoysa, Elhart, Van der Gert, De Lay, Moldrich, Wouterz, Solomons, Jansen, Roberts, De Saram, Nicolle, Schrader, Forbes and Hepponstal. Most were unaware this morning that Peradeniya was to be only a short stopover, on their way to Melbourne.

The government’s language policy change, displacing English was a year later. Hepponstall sensed the change. He migrated to Melbourne after only one term in Peradeniya, causing Vanderdergert to quip, “What happened to Hepponstall can happen to us all”. And it eventually did. A lost tribe of Lanka. Still identifiable mainly in Melbourne.

Soon the station platform was again empty. Vans organized by the university transported the freshers to their halls of residence where a small number arriving in their parent’s cars were already establishing themselves.

A wonderful blessing of nature and human architecture was to be theirs for the next three or four years.Beyond the promise of this bend in the river on either side spread the also alluring country that sustained it. This island’s modern history, a trajectory, which Aristotle would have called a given Plot or circumstance could not leave its first university untouched, as this story will unfold.