Confronting Charlie Ponnadurai: Clarifying the Context of Disparaging Ethnic Epithets in Sri Lanka over the last 180 years – By Michael Roberts

Charlie and I go back a long way – to Ramanathan Hall at Peradeniya University where we were freshers together in 1957 and thus were ragged together.[1] Charlie was known then as Charlies Ponnadurai, but he is now a “Sarvan” and resides in Germany with his German wife after years of work in Zambia and the Middle East. He has done me a singular honour in basing an essay on “Para Dhemalā” purely on my work. The reference is to “Pejorative Phases: the Anti-Colonial Response and Sinhala Perceptions of the Self through Images of the Burghers.”

Charlie and I go back a long way – to Ramanathan Hall at Peradeniya University where we were freshers together in 1957 and thus were ragged together.[1] Charlie was known then as Charlies Ponnadurai, but he is now a “Sarvan” and resides in Germany with his German wife after years of work in Zambia and the Middle East. He has done me a singular honour in basing an essay on “Para Dhemalā” purely on my work. The reference is to “Pejorative Phases: the Anti-Colonial Response and Sinhala Perceptions of the Self through Images of the Burghers.”

Readers may have been misled into thinking this was either a book or an independent article. Not so. The title is that of a chapter, “Pejorative Phrases….,” which is the first chapter in the book People Inbetween. The Burghers and the Middle Class in the Transformations within Sri Lanka, 1790s-1960s,” – a large tome published in Sri Lanka in 1989 by Sarvodaya Book Publishing Services. This book was one part of a longer projected series involving myself, Percy Colin-Thomé and Ismeth Raheem. That venture was inspired in part by our discovery of a treasure trove, namely, the Lorenz Collection at the library of the Royal Asiatic Society in Colombo. It has not seen the fullest fruition; but the first step was People Inbetween which was almost wholly my work, albeit aided by citation-aid and other inputs from Colin-Thomé and Raheem.[2]

Many people have mistakenly considered that book to be a history of the Burghers. Not so. It is a social and political history of the period 1790s to 1960s, one which focuses on the growth of the Sri Lankan middle class and marks some of the political currents of that era. Central to this process was the establishment of capitalist market relations by the British colonial dispensation and the transformation of the island through the creation of a road, rail and communication network, the establishment of cash crop plantations and a modernized administration. The “middle class” is conceptualized as a “status group” that overlapped with an emerging indigenous capitalist class without being synonymous with the latter.

A command of the English language and a gentrified life style was a critical aspect of the indigenous middle class, an emergent body of people who worked under and within the shadow of the ruling British functionaries, merchants and planters in the colonial order. The upper layers of the Burgher population secured a major role in the emerging indigenous middle class because (a) they were located in key urban nodes such as Colombo. Galle, Jaffna, Kalutara; and because (b) they had the requisite language skills and life practices to fulfill some of the intermediary roles created by the new dispensation; while yet being (c) deemed inferior by the race-conscious British, who kept them at a social distance for the most part.

It was from such circumstances that a few Burghers initiated the journal Young Ceylon in 1850-52, a literary and political magazine that provided the first sign of Ceylonese nationalist thinking opposed to “colonial subordinations.” Again, when the Ceylonese assembled a cricket team to challenge the local Europeans in a Test Match in 1887 in what was a form of sports nationalism the eleven players were all Burgher.

Our reading of such developments would also profit from attention to the demographic backdrop. Note that in 1921 there were 14,863 “Burghers & Eurasians” in Colombo, making up as much as 6 per cent of the people in the city as it was then constituted – even though they were less than one per cent of the total population in British Ceylon then (see People Inbetween for the statistical and other details).

In fact People Inbetween is as much a history of Colombo as anything else. One chapter is devoted to examining the place of that city in the capitalist-cum-political transformation of the island. The contention is that Colombo became a dominating hegemonic centre, one that loomed over the island economy at the same time that it established the guiding life styles and served as ideological epicentre.

That, then, is the broader setting within which “Pejorative Phrases” as opening chapter elaborates on the ethnic differentiations that developed in the course of the occupation of the island by various European powers beginning with the Portuguese. The emergence of mixed blood indigenous residents who came to be identified from the British times as “Burgher”[3] – by selves as well as others – was one consequence of this process. That is why the book, that is the first segment in chapter One, begins with a conjectural hypothesis on my part, a deciphering of the famous tale delineating how the local Sinhalese expressed astonishment when sighting the first Portuguese conquistadors: “kudugal sapākana le bona minissu!”[4]

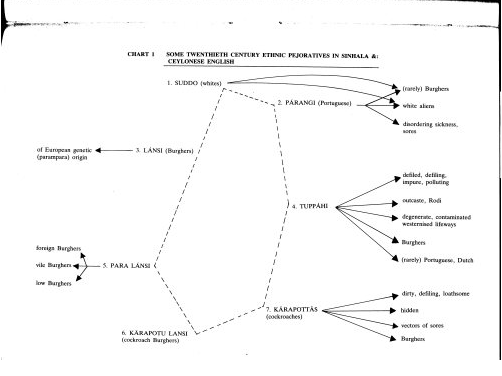

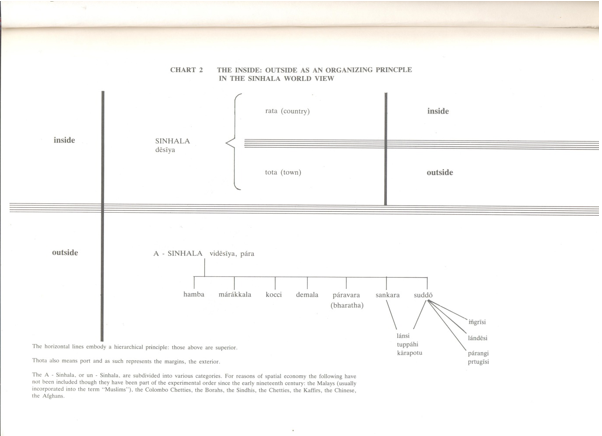

This context, in its turn, is essential background for our comprehension of such terms as para lansiyā, kärapottā, parangiyā, thuppahiyā and thus to further extensions embracing other non-Sinhalese – for example, para demalā.

Pejorative Phrases: “Pejorative Phrases” is a long chapter of some 21 large-size pages. It is not easy to summarize. While Charlie’s essay does not misread as such, the brevity of his article inadvertently misleads through absence of context. His emphasis runs thus: he pinpoints the Sinhalese hatred towards things foreign in order to “preserve what is believed to be pristine … and therefore sacred.” He then says that this emphasis was due to “a conviction that they are a chosen people” — a conviction that led to “an emphasis on purity” (all my words in quotation).

This particular summary is from page 14 of People Inbetween. It is not a misquotation. However, it is without its particular context. That specific theme was presented by me within a sub-section entitled “Weapons of the Downtrodden.” Here, at the outset of this sub-section, I commence by stressing that “such pejorative phrases as paralansiya and karapotu lansi … were counterpoints.” I then go on to say: “the pejorative expressions are (were) one part of the anti-colonial response. As such, they are (were) part of the armoury of liberation.”

Piyadasa Sirisena

It is at this moment that I inserted a Chart depicting the pejorative phrases in schematic form that clarified there linkages and context (see below). It is, I emphasise, on this foundation that I highlighted the emphasis on somatic purity (blood, race) in some strands of nationalist thinking. That is, I marked the emphasis on “debasing mixtures” of blood in the literature and essays produced by some Sinhala nationalists. I amplified this theme by focusing on the writings of the highly influential journalist, novelist and activist, Piyadasa Sirisena (1875-1946), whose thinking in my surmise was of greater consequence in his own time than that of Dharmapala. As I emphasised: “to be samkara was to be debased. Behind this was a crystallization of caste thinking in ethnic terms.”

Indeed, the central thrust in this chapter is about the manner in which caste ideology fused with the specific forms of racial thinking that had been introduced and consolidated by the colonial powers – so that the sub-section that follows is entitled “Caste Ideology within the Ethnic Stereotype.”

In brief, to repeat, the chapter cannot be readily summarized. But readers here can gain some sense of its breadth if I delineate the sub-headings in their temporal order:

The Story of the Arrival of the Portuguese

Parangi

Analogic Extensions

The Contexts of Banter and Abuse

Paradēsakkāra: Towards 1956

Burgher Airs and Prejudices

Weapons of the Downtrodden

Caste Ideology within the Ethnic Stereotype

Disordering, Craving

The Outside-Inside Metaphor and the Sinhala Body Politic.

The two charts I have composed for this chapter also serve as shorthand tools that clarify the context and the implications. The message, then, is that (1) the colonial context and its varying histories provided the enabling conditions for the creation and implementation of these forms of differentiation and disparagement; and that (2) these usages were part of a complex world of interchange and confrontation, a vortex where all parties were guilty of prejudice and intolerance. These prejudices could be on class lines. Thus, in the early decades of the 19th century for instance there was differentiation among the Burghers, between the superior lansi and the inferior tupass or thuppahi; and in the 20th century one found distinctions between “front door Burghers” and “back door Burghers.”

The further point (as an addition here in this new essay) is that the Sri Lanka Tamils were not bereft of extreme prejudices either and that some Vellalar in particular are known to have had extreme caste and/or racial prejudices. There is anecdotal evidence of considerable weight[5] regarding the extreme forms of disability faced by the dalit castes[6] of the Jaffna Peninsula even in the third quarter of the 20th century, evidence supported by some studies.[7] So, the issue then is this: what of the Tamil-speaking world of disparagement? From anecdotal conversations I am aware that the term parangi was part of the Tamil order. It referred to “aliens and “foreigners” and could be highly disparaging. We are in need of a historical sociology which unpacks the use of demeaning ethnic and caste terminology among the long-resident Tamil peoples of Sri Lanka over a period of time. The gentility of the Tamil people of Jaffna and elsewhere remains unstained only because such aspects are clouded by silences/absences; and by lacunae in the surveys of contemporary literature in Tamil.

Extensions: That then is the backdrop to the particular motifs that Charlie has gathered from my chapter to illustrate the use of the term para demalā in our generational time from the 1950s and thereafter. The use of that phrase, I add, was one facet of a whole corpus of pejoration that goes back to the 19th century. These disparaging acts of denigration were not confined to interpersonal banter or verbal confrontation. The foreigners who were targeted in news item or, on occasions, public platform in the colonial period included the British, the kocci (the Malayalis), the hamba (Indian Moors), the marakkala (all Moors), the hetti (Chettiyars),the javo (Malays) the bhai (Borahs, Afghans) and the para demala (low and vile Tamils).[8]

Such practices of intolerance and ethnic prejudice certainly provide food for thought and grounds for criticism. Such data also enables contemporary writers opposed to the present Sinhala-dominated order to cast Sinhala society in an unfavourable light. So Charlie’s little piece is par for the course in the prevailing propaganda war. To those attuned to little signs, his passing shot at my recent writings[9] indicates clearly where he is coming from.

Other essays and communications from time to time encourage me to position Charlie as a Tamil nationalist, one who is not on the extreme end of the scale, but who is yet far from moderate and somewhat to the right of centre.[10] There are many shades of Tamil extremism and even those of ‘lighter shade’ provide fodder for continued strife and hinder reconciliation.

Charlie’s concluding note in “Para Dhemalā” provides further proof of prejudiced readings of history in ways that serve a campaign of insidious warfare. He underlines his emphasis on the strands of racial superiority and purity in Sinhala nationalist thinking by alluding to the use of the term “Indian Tamils” in Sri Lankan nomenclature and moving to this concluding sentence: “then one should also speak of ‘Indian Sinhalese’: polluted or pure, the roots are the same.”

This is poor sociology, mindless stuff. The term “Indian Tamils” came into being and took root in British times in the 19th century. When Tamil-speakers from southern India were promoted and induced to travel to the hill country in the southern half of the island from the 1830s to work on the plantations and a large mass gathered in those parts, they were distinguished from the locally resident Tamils in the island by this term, namely “Indian Tamils.” It was not ‘merely’ a bureaucratic classificatory term adopted in the Blue Books, censuses and administrative language. The term derived from manifest differences in life ways, as well as phonetic dialect differences and other linkages. The differentiation was founded and girded by subjectivity forged in daily interpersonal exchanges (as with most collective identities). Most “Indian Tamils” remained aware of, and attached to, their ur back home in India.[11] Even as late as the mid-20th century Muttiah Muralitharan’s grandfather went back to his ur village, Namakkal, even though his son (Murali’s father) had advanced his fortunes and become a confectionary producer of some magnitude.[12]

In brief, there were subjective as well as manifest differences between the recent migrants from southern India and the Tamils long-resident in the northern and eastern parts of the island. This differentiation was underlined by the force of caste prejudices amongst the local Tamils, those identified as “Ceylon Tamils” (now Sri Lanka Tamils). As some Ceylon Tamils gained jobs in the plantation sector as apothecaries, tea-makers etcetera or moved into the hill-country as state functionaries, their sense of superiority and their prejudices towards the “Indian Tamils” were only too evident. This is a well-established fact in the oral history carried in the memories of older Ceylonese/Sri Lankans. If one has any doubts one should ask Sebastian Rasalingam, the octogenarian of non-Vellalar caste who happened to marry an “Indian Tamil” (Estate Tamil, Malaiyaha Tamil) and lived in Hatton for a while; and whose tales about Vellalar practices of superordination are as deadly as revealing. Notions of superiority, whether based on caste prejudice, gentility or otherwise, do generate recoil. That was my point about Sinhalese reactions to White colonial ideas of racial superiority. This does not justify the xenophobic lengths to which the Sinhalese recoil was taken and/or its further extensions to other outsiders. Parenthetically, I note here that the issue NOW is whether the type of recoil among Tamils of the diaspora displayed by Charlie in his occasional public writings serves the cause of the Tamils who have chosen to live in Sri Lanka today and the cause of Sri Lanka writ large.[13]

Be that as it may, the emergence of the category “Indian Tamils” in British times did not displace the widespread understanding that Sinhala-speaking peoples had migrated from India way back in the last millennium BC and subsequently. That was the overpowering theme in both the vamsa chronicles and the oral traditions of the Sinhalese. This theme was absorbed by the British writers and colonial administrators. A sub-theme referred to Tamil invaders at specific times in the distant past, while oral traditions indicated that there had been migrants from India who had been absorbed into the Sinhala-speakers in medieval times.[14]

Thus, Charlie’s concluding note about Indian Tamils and racial/blood lineages is a form of one-upmanship inspired by Tamil extremism in the present context of propaganda war. It also happens to be arrant nonsense that defeats its purpose.

REFERENCES

Bass, Daniel 2001 Landscapes of Malaiyāha Identity, in A History of Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka: Recollection, Reinterpretation and Reconciliation, Colombo: Marga Monograph Series, No 8.

Daniel, E. Valentine 1997 Charred Lullabies: Chapters in an Anthropography of Violence, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dharmapala, Anagarika 2010 “Kocci Demala,” Sinhala Bauddhaya, 14 January 2010.

Jayatilleka, Dayan 2010 “Charlie Sarvan’s War,” 28 Nov. 2010, Sunday Leader, http:// www.thesundayleader.lk/2010/11/28/charlie-sarvan%E2%80%99s-war.

Jayawardena, Elmo 2011 “A Different Voice: Review on ‘Public Writing on Sri Lanka’ by Prof Sarvan,” The Island, 29 Jan. 2011, http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=17095.

Jayaweera, Neville 2011 “The Caste Factor in the Tamil Nationalist Uprising,” 22 Jan 2011, http://transcurrents.com/tc/2011/01/the_caste_factor_in_the_tamil.html.

Malalgoda, Kitsiri 2010 “1505 and All That: Varied Views of a First Encounter,” in Home and the World. Essays in Honour of Sarath Aunugama, Colombo: Ace Printing & Packaging Ltd, pp. 227-57.

Pfaffenberger, Bryan 1982 Caste in Tamil Culture. The Religious Foundations of Sudra Domination in Sri Lanka, Maxwell School of Foundations and Comp Studies.

Pfaffenberger, Bryan 1994 “The Political Construction of Defensive Nationalism,” in C. Manogaran & B. Pfaffenberger (eds.) The Sri Lankan Tamils, Boulder: Westview Press, pp. 143-68.

Rajasingham, Narendran 2011 “Caste in the Jaffna Peninsula,” 1 July 2011, http://thuppahi.wordpress.com/2011/07/01/caste-in-the-jaffna-peninsula/

Roberts, Michael 1989 “A Tale of Resistance: The Story of the Arrival of the Portuguese in Sri Lanka,” Ethnos, 55: 69-82.

Roberts, Michael 1994 “Mentalities: Ideologues, Historians and the Pogrom against the Moors in 1915,” in Roberts, Exploring Confrontation, Reading: Harwood Academic Publishers, pp. 183-212.

Roberts, Michael 2001 Sinhala-ness and Sinhala Nationalism, in A History of Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka: Recollection, Reinterpretation and Reconciliation, Colombo: Marga Monograph Series, No 4.

Roberts, Michael 2002b Primordialist Strands in Contemporary Sinhala Nationalism in Sri Lanka: Urumaya as Ur, in A History of Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka: Recollection, Reinterpretation and Reconciliation, Colombo: Marga Monograph Series, No 20.

Roberts, Michael 2003b “Language and National Identity: The Sinhalese and Others over the Centuries,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, Summer 2003, 9: 75-102. Also in http://www.academia. edu/3793599/Language_and_National_Identity_The_Sinhalese_and_Others_over_the_Centuries

Roberts, Michael 2012 “Caste in Modern Sri Lanka Politics,” 22 February 2010, http://transcurrents.com/tc/2010/02/caste_in_modern_sri_lankan_pol.html

Russell, Jane 2012 “Jane Russell’s Reflections on Oppression, Violence and the Paths of Response available to Us All,” 13 Sept. 2012, http://thuppahi.wordpress.com/2012/09/13/ jane-russells-reflections-on-oppression-violence-and-the-paths-of-response-available-to-us-all/

Sarvan, Chales 2011 “Reign of Anomie” in Sarvan, Public Writing on Sri Lanka,

Sarvan, Charles 2013 “Para Dhemalā,” 16 August 2012, in http://thuppahi.wordpress.com /2013/08/16/para-dhemala/#more-10208.

Thambinayagam, Pearl 2011 “Pernicious Caste Curse of Tamils living in the Dark Ages,” 30 June 2011, http://www.srilankaguardian.org/2011/06/pernicious-caste-curse-of-tamils-living.html

Tiruchelvam, Nirgunan 2006 “Murali scales the Summit,” in Michael Roberts, Essaying Cricket. Sri Lanka and Beyond, Colombo: vijitha yapa Publishers, pp. 241-43.

[1] On one occasion I found myself assembled together in one room of a Thomian second year with Charlie. Anton Tissera, and Neville de Alwis where we four were subject to verbal ragging by a cluster of Thomian seniors. To this day I remain puzzled as to HOW I was among the Selected. I was never ever a Thomian!

[2] For another step, see Raheem and Colin-Thome, Images of British Ceylon. Nineteenth Century Photographs of Sri Lanka, Singapore: Times Editions, 2000, ISBN 981 204 7786.

[3] In Dutch times in the 17th and 18th century the term Burgher referred to the free European settlers and did not encompass the VOC officials and soldiers. Thus, the reference in this article and in People Inbetween is to its modern post-British usage.

[4] This section has been improved and expanded in a separate article “A Tale of Resistance: The Story of the Arrival of the Portuguese in Sri Lanka,” Ethnos, 1989b 55: 1-2:69-82. For a fascinating criticism directed at my thesis, see K. Malalgoda 2010.

[5] For instance from the written web comments from Jane Russell presenting her experiences of Jaffna in the 1970s (one example is Russell 2012) and from the autobiography by Neville Jayaweera describing his time as GA Jaffna. Also see Rajasingham 2011 and Thambinayagam 2011

[6] That is, those called “low castes’’ and “pariah” in the generic sense of the latter term.

[7] E.g. Pfaffenberger 1982 7 1994; Russell 2012; Rajasingham 2011 and Thambinayagam 2011

[8] See Roberts 1994: 199-201 and Dharmapala 1911.

[9] “I think even those who have recently expressed disappointment with him [in recent times for his recent essays]….”

[10] My reading of occasional essays and notes sent to me in recent times, but also see Dayan Jayatilleke 2010 and especially the moderate review by Elmo Jayawardena 2011.

[11] See Bass 2001. Also note Daniel 1997.

[12] Tiruchelvam 2006: 241.

[13] Note Elmo Jayawardena’s review of Public Writing (2011).

[14] Thus, segments of the Karava, Salagama, Durava castes were widely believed to have migrated in late medieval and early modern times.