From Pettah to Cotta-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

Historically, the city of Colombo always faced a conflict, or contradiction, between an almost endless set of high-rise buildings and largely poorly constructed streets. As far back as 1907, for instance, it was observed that “large improvements would have to be carried out in the direction of widening such streets, while legislation by the Municipal Council should be enacted to “fix the line of streets and prevent encroachment thereon”, which would have saved money spent on buying buildings, “the erection of which ought never have been allowed.” The gap between the affluent and depressed wards not surprisingly became a cause for worry: the “native wards” were all “deficient”, with the exception of the European and chief residential quarters, which appeared “well provided.”.

There was, of course, a Colombo that existed before all this. The Rajavaliya referred to it as “Kalan Thota” or “Kelani Ferry.” Emerson Tennent has noted that the Moors, who took over the coast and harbour in the 12th and 13th centuries, renamed it as “Kalambu” or “a good harbour.” It gained prominence gradually thereafter: Ibn Batuta would describe it as “the finest town in Serendib.” The town remained under the control of a Muslim Vizier named Jalestie. Tennent observed that this was because the Sinhalese were uninterested in trade, which is somewhat true: as K. M. de Silva notes in A History of Sri Lanka, the principal source of royal income in Kotte was not trade, but rather land revenue.

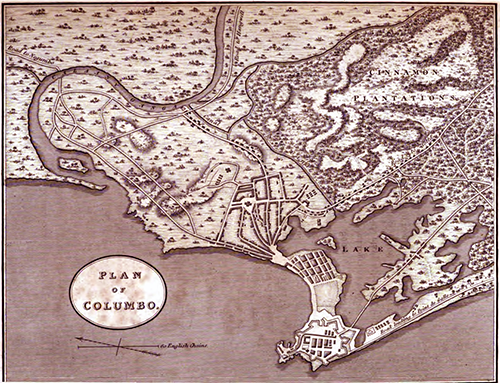

Kotte would, of course, bear witness to two wars of succession, both compounded by Portuguese presence in the island. The latter were concerned with two priorities: gaining a monopoly over the cinnamon trade, and establishing commerce in Colombo.

According to de Silva, the first objective was generally considered less important than the first, but it nevertheless was crucial for the ambitious imperialists to gain control over the area; to this end they established an unfortified fort in Colombo for trading purposes. It is with the advent of the Portuguese, moreover, that Kalambu became Colombo: a name that more or less “approached that of Columbus”. But it was more than a change of name: as the Census of 1946 notes, under the Portuguese the city transformed from “a small stockade of wood” to “a gallant city fortified with a dozen bastions.”

But the Portuguese and the Dutch after them had to contend with two seemingly never-ending conflicts in the country: between the Kotte Kingdom and colonial authorities on the one hand and the Kotte Kingdom and pretenders from Sitawaka and Kandy on the other. The wars of succession weakened Kotte, and the Sinhalese monarchs, whose interest in trade depleted, in effect handed over commercial matters to colonial authorities. Despite this, however, authorities were never able to expand the city beyond Pettah, “between the lake at one side and the rocks, which form the harbour, on the other.” It was left to British officials to develop Colombo into more than just a military enclave.

To begin with, the British made use of what the Portuguese and the Dutch had left behind. The former especially had turned Colombo into a fortress. After the conquest of Kandy in 1815, the British began tapping into the region’s commercial potential in a way their predecessors had not. Once again it was the port which facilitated this shift in policy; by 1907 it had become “one of the principal ports of call of the world”, and was described as “the Clapham Junction of the East.” The British added a railway system to the shipping line; here too Colombo became the centre. Over the years the Fort area changed: it became a hub for government establishments, banking houses, and European businesses.

Interestingly, despite its veneer of sophistication and grace, British officials were not impressed with the new capital. “Colombo presents little to attract a stranger,” noted Tennent in 1859, and he had much to complain about: “the prevalence of damp”, “the nightly serenade of frogs”, and worst of all, “the tormenting profusion of mosquitoes” which had lead to outbreaks of dengue that had never visited the better developed areas of the municipality. Through all this, incidentally, a gap emerged between the centre and the periphery, in effect between the affluent and the indigent wards.

At first it was the areas developed by the Portuguese and Dutch which became hotspots for the colonial officials and the native elite. The area from Fort to Hulftsdorp, which James Cordiner had once described as “a more comfortable residence for a garrison than any other military station in India”, would in 40 years turn into what Prince Alexey Saltykov described as “a botanical garden on a gigantic scale.” This was facilitated by several factors: the breakdown of the old order, the shift from the interior to the littoral, and the emergence of a plantation economy. Moreover, Prince Saltykov made his remark about Colombo at a time when the old elite was yielding place to a new bourgeoisie.

The transition from a mercantilist to a semi-feudal economy in the first half of the 19th century was accompanied by the rise of a new colonial bourgeoisie. While the traditional elite had depended on the patronage of the British officials in terms of land bequests and perpetuation of familial dynasties (which led to the concentration of power within the Bandaranaike-Obeyesekere clique), the bourgeoisie took advantage of favourable economic conditions and prospered through capitalist-rentier enterprises.

Arrack renting became the main avenue of growth for the nouveau riche; by 1876 the annual rents from this trade amounted to £ 218,600 (£ 28,035,560 or Rs. 12,093,260,379 when adjusted for inflation). Profits from the arrack trade, however, were never invested in productive enterprises (as they were in other colonies) and were instead invested in coffee, coconut, graphite, and plumbago on the one hand and items of conspicuous consumption which helped distinguish them from the rest of the country on the other. Property in this regard was seen as paramount; it had a say in how the “posh neighbourhoods” shifted from Pettah, Hulftsdorp, and Maradana to Cotta, Colpetty, and Cinnamon Gardens.

Initially, the elite purchased land in the Pettah-Maradana-Kotahena-Mutwal area. Even in the last few decades of the century these places were at the forefront of British colonial activity in terms of commerce and education: all the major credit institutions were in the Pettah, while the two biggest schools in the country (one public, the other private) were established there: the Colombo Academy in Hill Street (the first batch of which consisted of 21 students from elite Burgher families within the neighbourhood, among them Richard Morgan, Charles Loos, and Christoffel de Saram) in 1836, and S. Thomas’ College in Mutwal 17 years later. This is certainly not to forget the Medical College and the Law College, built respectively in 1870 and 1874.

These trends were reflected in the lands purchased and palatial residences built during the period: Solomon Dias Bandaranaike, S. C. Obeyesekere, and G. G. Ponnambalam all built their manors in Hulftsdorp. Vinod Moonesinghe contends that long before Cinnamon Gardens became a plush neighbourhood, “the prime residential areas were Mutwal (for Europeans) and Kotahena (for locals), plus Grandpass for ‘country homes’.”

According to Moonesinghe, land values in Cinnamon Gardens rose after the Race Course moved from Galle Face, and the “process of gentrification” in the area culminated when Royal College shifted to its current location in 1912. But even then, this process was not fully complete: as Denham notes in Ceylon at the Census of 1911, while land in Cinnamon Gardens fetched Rs. 5,000 per acre, land near the Slave Island, Maradana, and Pettah stations fetched more than four times that amount. In other words, it would take another 30 years for the shift from one part of Colombo to another to complete.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com