How new finds are changing Buddhist history – I-by Rachel Lopez

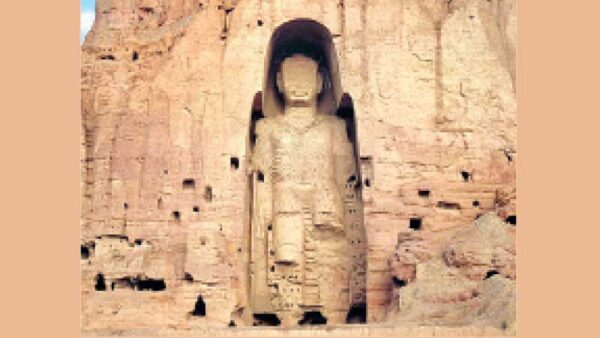

One of the colossal Buddha statues in Bamiyan

Source:Dailynews

Buddhist history is turning a corner. New finds suggest that it spread wider, lasted longer and was more influential than we realised. it is time to update the map.

Across Asia, geography is changing history. A slew of excavations and chance discoveries show that the history of Buddhism, the belief system that flourished from 600 BCE until a decline in the 13th century CE, still contains many surprises.

Newly unearthed sites in Uzbekistan are evidence that it spread farther than previously thought. Stupas and sculptures dating back 2,000 years show that it flowed into new territories earlier. And magnificent monastery complexes are proof that the Buddhist institutions exerted greater influence over commerce, urban development, economic systems and everyday life than previously thought.

Emerging from the digs are stone structures, coin caches, copper plates, mantras punched on gold foil, inscriptions on palm leaf and ivory, colourful murals, and scriptures in at least 20 languages. How did Buddhism, which preached a renouncement of the material world, leave behind such a staggering wealth of physical evidence? K.T.S. Sarao, former head of Buddhist Studies at the Delhi University, says that a mingling of the sacred and non-sacred was inevitable. “Monks spreading the Buddha’s teachings would travel along the Silk Road with merchant groups for safety; merchants, in turn, relied on them for spiritual support on these risky journeys,” Sarao says.

Emerging from the digs are stone structures, coin caches, copper plates, mantras punched on gold foil, inscriptions on palm leaf and ivory, colourful murals, and scriptures in at least 20 languages. How did Buddhism, which preached a renouncement of the material world, leave behind such a staggering wealth of physical evidence? K.T.S. Sarao, former head of Buddhist Studies at the Delhi University, says that a mingling of the sacred and non-sacred was inevitable. “Monks spreading the Buddha’s teachings would travel along the Silk Road with merchant groups for safety; merchants, in turn, relied on them for spiritual support on these risky journeys,” Sarao says.

Over time, shrines sprouted at rest stops, becoming a constant in an uncertain landscape. “They grew to include storehouses, factories, banks, and guesthouses, allowing monks to benefit not only from royal patronage but from local commerce too.”

In Bihar, where the Buddha is said to have attained enlightenment, efforts are on to unearth an administrative centre that until now only existed in texts. A monastery headed by a woman has been found there, and in Odisha, there is evidence of an unusual meditation complex open to both monks and nuns. In Afghanistan, monasteries located alongside copper mines reveal how rich monks wielded clout over the region.

Archaeology, then, is recreating parts of the story that are not found in the scriptures. Because of the Buddha’s renunciation of material possessions and the self — he told followers he should not be the focus of their faith — there are key questions that are still unanswered. Researchers are hoping to confirm whether Kapilavastu, the Buddha’s childhood home, corresponds to the town in Nepal or one of the same name, not far away, in Uttar Pradesh. They are tracking how his teachings travelled clockwise out of central India, spreading through north-west Asia and then to China and further east over 1,000 years.

“Sri Lanka, Thailand and Myanmar have done admirable jobs of preserving Buddhist monuments,” says Sarao. In India, however, unmarked Buddhist sites are often mistaken for Hindu temples by locals. Idols of Buddha are worshipped as Shiva, Ashokan pillars are taken for lingams. “We should work together to preserve the Buddha’s legacy,” says Sarao. “His teachings are more relevant than ever.”

“Sri Lanka, Thailand and Myanmar have done admirable jobs of preserving Buddhist monuments,” says Sarao. In India, however, unmarked Buddhist sites are often mistaken for Hindu temples by locals. Idols of Buddha are worshipped as Shiva, Ashokan pillars are taken for lingams. “We should work together to preserve the Buddha’s legacy,” says Sarao. “His teachings are more relevant than ever.”

Across the arid Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, which encompasses much of the north and northwest of Pakistan, lie some 150 Buddhist heritage sites. The area was a major centre for early Buddhist development under Ashoka’s reign 2,300 years ago.

Italian archaeologists were investigating the province’s northern Swat region as far back as 1930. But digs were abandoned before discoveries could be made. Local teams, back at the site last year, were luckier. They discovered a monastery and education complex, the largest found in the region, and believed to be between 1,900 and 2,000 years old. Discovered thus far are stupas, viharas, a school and meditation halls, along with smaller cells higher in the mountains where monks could retreat into isolation. Also unearthed was a coin, helping date the site to the Kushan Empire (30 CE – 375 CE), which spread across modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India and was instrumental in spreading Buddhist teachings. The bonanza: rare frescoes depicting figures in various poses, including the namaskar.

Afghanistan’s chance to make amends

It has been 20 years since the Taliban destroyed the Buddha colossi in Bamiyan. They still could not erase signs of Buddhism, which had a large following here until the 11th century. Cave networks, paintings and statuary have been found at six major sites.

It has been 20 years since the Taliban destroyed the Buddha colossi in Bamiyan. They still could not erase signs of Buddhism, which had a large following here until the 11th century. Cave networks, paintings and statuary have been found at six major sites.

In 2008, when the Chinese bought over the world’s second-biggest unexploited copper mine in Mes Aynak, the site of an ancient Buddhist settlement, archaeologists raced to document and salvage the 2,600-year-old monastery that stands there, before it was lost forever. Mes Aynak was a spiritual hub along the Silk Road from the 3rd to 8th centuries CE, a peaceful cosmopolitan pitstop run by monks who’d become rich from the copper ore. Researchers unearthed monastery complexes, watchtowers, walled zones, jewellery hoards, manuscripts and close to 100 stupas. One statue of the Buddha, twice as tall as a human, still bore traces of red, blue and orange on the robes. Several copper coins featured an image of the Kushan emperor Kanishka on one side, and the Buddha on the other.

As a result of Afghanistan’s poor infrastructure, mining work has stalled. Archaeologists could not be happier. Their initial three-year deadline for digs has stretched to nearly 13 years already, becoming the most ambitious excavation project in Afghanistan’s history. In 2016, when a mural was discovered in Termez in southern Uzbekistan, near today’s border with Afghanistan, few were surprised. Uzbekistan was, after all, once part of the Kushan Empire. Its residents were intermediaries as goods flowed west to Rome and east to China.

But the mural was unusual. It was discovered in a stone basement adjoining a pagoda and looked to have been made in the 2nd or 3rd century CE. Despite its age, its figures in blue and red were remarkably vivid, blending influences from East and West, its angled face shaded to mimic depth. It seemed to be part of a lost larger painting about the life of the Buddha. Researchers drew parallels with murals in Dunhuang, China, an eastern junction on the Silk Road. It was proof that the route did not just transfer things, it let art, religion and ideas flow in both directions too.

Nepal’s tryst with history

The Buddha disapproved of the idea of devotees focusing on him, and so little about him and his life is known. Followers believe that his mother, en route to her parents, went into labour and gave birth to him (grasping the branch of a sal tree) in the Lumbini garden in present-day Nepal. We know that Emperor Ashoka built the first Buddhist structure there — a pillar inscribed with his own name, the story of the Buddha’s birth, and a date corresponding to the 3rd century BCE.

That spot is now a UNESCO world heritage site. But in 2013, when British archaeologist Robin Coningham excavated inside the 3rd century BCE Maya Devi temple that also stands there, he found that the site (and Ashoka’s story) went deeper. Beneath the temple his team found a roofless wooden space, with signs of ancient tree roots over which a brick temple had once been built. Charcoal and sand fragments were carbon dated and found to be from 550 BCE, around the time the Buddha is said to have lived. If this was a Buddhist shrine, the timing would make it the first one ever built. Indian archaeologists are sceptical, though. “Tree shrines have been part of Hindu worship much earlier than the time of the Buddha,” says K.T.S. Sarao, who is also a former classmate of Coningham at Cambridge. “It is not unusual for temples to be renovated and there is no proof connecting it to the Buddha.”

That spot is now a UNESCO world heritage site. But in 2013, when British archaeologist Robin Coningham excavated inside the 3rd century BCE Maya Devi temple that also stands there, he found that the site (and Ashoka’s story) went deeper. Beneath the temple his team found a roofless wooden space, with signs of ancient tree roots over which a brick temple had once been built. Charcoal and sand fragments were carbon dated and found to be from 550 BCE, around the time the Buddha is said to have lived. If this was a Buddhist shrine, the timing would make it the first one ever built. Indian archaeologists are sceptical, though. “Tree shrines have been part of Hindu worship much earlier than the time of the Buddha,” says K.T.S. Sarao, who is also a former classmate of Coningham at Cambridge. “It is not unusual for temples to be renovated and there is no proof connecting it to the Buddha.”

He adds a further blow: The Government of India does not permit foreign archaeologists to dig here. So some scholars may exaggerate foreign findings to make them sound as important as the sites they cannot access, he says.

Meanwhile, work continues in Nepal. Coningham’s excavations in the Tilaurakot region, where the Buddha was believed to have lived as Prince Siddhartha, have unearthed the remains of an 1,800-year-old palace complex and walled city. There are courtyards, a central pond and stupas. But still no concrete connection to the Buddha.

(Hindustan Times)