Into the Vanni and Jaffna of the 17th Century-by Darshani Ratnawalli

Source:Thuppahis

His name was Knox. Robert Knox. English. He was a prisoner in Lanka from 1660 to 1680. Finally he escaped from Kandy or more specifically from Rajasinha II, who claimed to be the sovereign overlord of the whole of Lanka and its people. The world-view Rajasinha II inherited as a ruler of Sinhalē (a perception of pan island chakravartihood) comes across in his correspondence with the Dutch. He told them that “the black people of this island of Ceilao, wheresoever they might be, [are] my vassals by right”- (Roberts: 2004[i]:78). In the royal view, the Dutch were the “faithful Hollanders, the guardians of his coast” and earlier during his enterprise to oust the Portuguese, they were “his hired guns”. In Rajasinha II’s early letters to the Hollanders (written in Portuguese) he was “The most potent Emperor of Ceilao” while they were “My Hollanders” and the fortresses held by them were “my fortresses” as in “my fortress at Gale”. What with “my black folk”, “my vidanas,” “these lowland territories of mine” and “my said island”, Rajasinha II was asserting that he “did not recognize Dutch claims to sovereignty over the coastal areas”- (ibid and Dewaraja 1995:189). The Dutch kept up the appearance of concurring with this assertion in their diplomatic relations. “The governor, Pijil, referred to himself as the “king’s most faithful governor and humble servant”, called the king “His Majesty” and spoke of “the king’s castle at Colombo.” He even “declared that all the island belonged to the Sinhalese King.”- (Roberts: 2004: 79).

In reality though, the Dutch were merely going through the motions of going along with the efforts to incorporate them into the Lankan scheme of things. They weren’t genuine stakeholders of it. That’s why Knox headed for Arippu. Once in Dutch territory he knew he would be safe. He had no fear of the faithful Hollanders, guardians of the sea coasts handing him back to the most potent Emperor. But on his way there, he had to cut across a certain territory, which lay outside the immediate realms of Rajasinha. In this territory he was afraid. Because unlike the Dutch, its ruler was an organic part of the Lankan scheme of things. He was a Vanniya. Let’s hear Knox on his ‘fears’.

“But yet we were somewhat dismayed, knowing that we were now in a Countrey inhabited by Malabars. The Wanni ounay or Prince of this People for fear pay Tribute to the Dutch, but stands far more affected towards the king of Cande.”- (Knox: 1681[ii], p166). Knox had been nervous from afar about his entry into the Wanni Unnehe’s country; “This People we were sorely afraid of, lest they might seize us and send us back, there being a correspondence between this Prince and the King of Cande, wherefore it was our endeavour by all means to shun them; lest according to the old proverb, we might leap out of the frying pan into the fire.”- (p157)

This Prince whom Knox calls “Coilat Wanea” has been identified (by Donald Ferguson) as being none other than the Kayla Vanniya, famous in the Dutch records for his liveliness. At one point during Rajasinha II’s reign, the Dutch found Arippu, which was critical for the security of the Pearl Fishery threatened by “the restlessness of Kayla Wannia who was acting in concert with Tennekon” who was Disawa of the Seven Korales and was “hovering near Kalpitiya with his men”.(P.E. Peiris:1918:22)

According to Knox (p175), the Hollanders had tried to subdue this “Coilat wanea” by wars, “but they cannot yet do it…The King and this Prince maintain a friendship and Correspondence together. And when the King lately sent an Army against the Hollanders, this Prince let them pass thro his Countrey; and went himself in Person to direct the King’s People, when they took one or two Forts from them.”

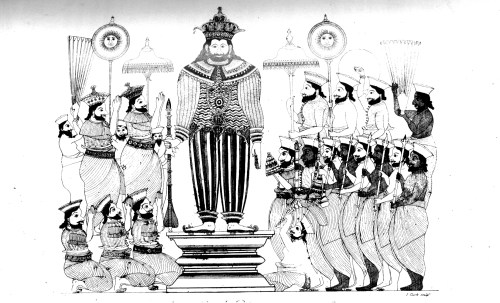

Rajasinghe II of Kandy as etched in Robert Knox (1681)

The exact nature of the Lankan status quo that birthed bonds like these between the centre and the periphery was for a long time unexplored and even ignored by present day historians. In the planet called Sri Lankan Historiography, most of the clues aren’t picked up because there aren’t enough Sherlocks.

Very few Sherlocks in professional historiography have picked up on Phillipus Baldaeus (A True and exact Description of the Great Island of Ceylon: 1672). He and Knox belonged to the same generation. Knox majored in the doings of the Kandyan Kingdom, while Baldaeus on the Dutch doings with a special focus on Jaffna. In 1658 when he accompanied the Dutch Troops as Chaplain and witnessed the capture of Mannar and Jaffna from the Portuguese, Baldaeus was 26 while Knox was 17 and still in England. That year, he was appointed the predikant over Jaffna and adjacent islands and spent the next 7 years in Lanka[iii]. Baldaeus informs us (Pieter Brohier[iv] translation; Ch.44: 316) that the Kingdom of Jafnapatan “remained under the Portugezen sway for upwards of 40 years, wrested from the Emperor by Philippo d’Olivero when he defeated the Cingalezen forces near Achiavelli by the great pagode…”

The “Emperor” of the above quotation was Senarat, who was the father of Knox’s King Rajasinha II and styled himself “Cenuwiraed by the Grace of God, Emperor of Ceylon, King of Candy, Setevaca, Trinquenemale, Jafnapatam, Settecorles, Manaer, Chilaon, Panua, Batecalo, Palugam[v] and etc. etc.-(Baldaeus: Ch.14: 70 and Bouchouwer:1931). Baldaeus wrote recounting events in 1612 that “While the Emperor’s attention was thus engaged, he received tidings that the Portugezen with a large force of armed men were making for Jafnapatan. The Emperor whose scheme of warfare had been only directed to Gale and Walane now dispatched some of his troops to meet and oppose the enemy’s progress. The latter falling in with the Portugezen troops in the rear soon put them to flight in great confusion.”(p56, Ch.11).

On two occasions (Once in 1613 as Senarat lay sick expecting death and earlier in 1612 when he is planning a major offensive against the Portuguese in the coastal areas.) Baldaeus listed among those assembled as Senarat’s Councilors of State, Namacar, Envoy of the King of Jafnapatan along with Idele, King[vi] of Cotiarum; Celle Wandaar, King of Palugam; Comaro Wandar, King of Batecalo and etc.-(p55 and 68).

Michael Roberts stands out as one of the few scholars to have explored these threads of cohesion which bound the peripheries to the centre of the pre-modern Lankan State aka Sinhalē. His analysis of the issue can be summarized under three broad headings.

First, the political mechanism or concept that sustained these threads was “Tributary Overlordship”, a different form of allegiance and rule which accommodated localized dominion and satellite states, thereby providing symbolic acknowledgement of the dominion attached to the superior Chakravarti figure.

Secondly the Chakravarti muscle was flexed when necessary. An instance is given by Baldaeus; “In September following there arrived tidings that the King of Panua had thrown off his allegiance and joined the Portugezen and that the King of Cotiarum was also plotting a revolt against the Imperial Crown when they were instantly summoned by letters dated 23rd September to make their appearance before the Emperor within 16 days under pain of confiscation of property and banishment”- (Chap.12: 60).

Thirdly, independent of force and obligation, there existed an element of sentimental or patriotic allegiance to the kingship of Sinhalē; “There are glimpses of allegiances to the King of Kandy that did not arise from force exercised by the latter. The evidence is indirect and emanates from incidents during the massive war of liberation against the British that developed in the years 1817-18 in many parts of the former Kingdom of Kandy. This was a struggle to restore the status quo ante and was therefore oriented towards a restoration of kingship, namely, a king of the Sinhalese. As such, a pretender king provided a focus for rebel loyalty. This king selected the shrine of Kataragama as his springboard and surrounded himself with a body of Vadda archers (P E Pieris 1995c: 277-80). Among those who joined the rebel forces one found (a) Kivulegedara Mohottala of Walapana, a headman of Vadda lineage, (b) several headmen in the distant Vanni areas of Bintanna and Wellassa and (c) Kumarasinha Unnahe of Nuvarakalaviya[vii]. These expressions of allegiance to the old order from such outlying localities is suggestive because British rule could not have had a severe material impact on such places in the course of two years. In other words, they suggest that the chieftains and headmen of the Vanni, the epitome of fissiparous principalities in the imagination of modern scholars, remained attached to the idea of Sinhala kingship”- (Roberts: 2004: 76)

@ http://ratnawalli.blogspot.com/ and rathnawalli@gmail.com

[i] Sinhala consciousness in the Kandyan period, 1590s to 1815, Michael Roberts, 2004

[ii] An Historical Relation Of The Island Ceylon In The East Indies Together With An Account Of The Detaining In Captivity The Author And Divers Other Englishmen Now Living There, And Of The Author’s Miraculous Escape

[iii] See Introduction to the Pieter Brohier translation of “A True and exact Description of the Great Island of Ceylon”: 1672

[iv] Pieter Brohier, the son of a Captain of the Dutch Army was born in 1792. Thus he is only 160 years younger than Baldaeus. “As a translator Pieter Brohier had several distinct advantages which make the present translation an accurate and useful one. He was born in Dutch times, learnt the language as a boy and continued to use it for a considerable time, for Dutch was the spoken language of the Burgher community well into the British Period. He thus had a sound knowledge of the language and was closer to the “High Dutch” of Baldaeus by well over a hundred years than present day translators. Similarly, as a public servant under the British colonial administration and having lived during the British occupation of Ceylon for over fifty years, Brohier had a good knowledge of English which enabled him to render the translation from the Dutch into English accurately. Besides as a Ceylonese he was able to translate properly oriental words, customs and descriptions given by Baldaeus, which for instance were wrongly rendered in Churchill’s English translation.”-(Introduction)

[v] Chilaon=Chilaw, Panua is Panama. Palugam has become Palukamam today. See Glossary of Place-Names by C.W. Nicholas given in the Pieter Brohier translation of “A True and exact Description of the Great Island of Ceylon”: 1672

[vi] The “Kings” referred to (except in the case of the King of Jafnapatan) are Vanniyas. So called due to their greater autonomy. In Sinhalese too they are called vanni rajavaru, vanni nirindu, vanni ranno.

[vii] This Kumārasinha Unnähē of Nuvarakalaviya was none other than the last Maha Vanniā under the Kandyan rule and the brother in law of Pandāra Vaniyā of Mulliyāveli.