Ivor Jennings and Peradeniya University in Two Excursions

Source:Thuppahis

ONE: ‘Varman’ = “Jennings and the Old Galaha Road”

In 1952 we lived on Old Galaha Road. That was the last year we lived there. The government of the day compulsorily acquired our house and the land for the campus of the new University of Ceylon at Peradeniya. Much against our wishes, we were on orders to quit our home. The order to vacate, after the property was compulsorily acquired by the government, came from the Vice Chancellor’s office, the new owner of what was our beloved property.

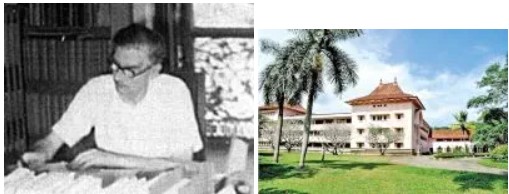

Sir William Ivor Jennings was the first Vice Chancellor of the University of Ceylon. He lived in his official residence right in the middle of the campus. Although the VC was the signatory, or on whose behalf the vacate order was signed, Jennings had nothing to do with such matters. All he dreamed of was to build a university replicating his alma mater, the University of Cambridge. Jennings was later to become the Vice Chancellor of Cambridge.

Peradeniya had the ideal setting for Jennings’ aspiration. In fact, Peradeniya was by far of greater natural beauty than Cambridgeshire. The Mahavali, which flowed through the campus grounds, is much more picturesque than the River Cam. Then there is the majestic Hantana range bordering the grounds, with its craggy rock face crowning the upper regions. And of course there was vastly superior Peradeniya Royal Botanical Gardens which is no match to the Cambridge Botanical Gardens. Nor could the Cambridge Lakes Golf Course match the scenic beauty of the Peradeniya Golf Course, which existed into the 1950s.

Jennings, in his memoirs posthumously published as “Road to Peradeniya”, says that when he drove up to Peradeniya in March 1941 and up the Old Galaha Road and finally waded through the shrubs towards the proposed site for the university, he saw the vision, and magnificent at that, of his new university, perhaps in the image of his much-loved Cambridge. It was an elite university that he dreamed of, a place to produce intellectuals, not a mass of humdrum men and women with worthless degree certificates. Peradeniya was never meant, never built, to mass produce graduates. Jennings wanted the place to supply the future leaders, the intellectual elites to lead the emerging independent Ceylon, and to wrench the leadership away from the moneyed socially elite class that took over from the departing Brits. That dream never materialised, but more on it later.

We lived on a quarter acre block between the Old and the New Galaha Roads, in front of the Department of Agriculture building. Our house faced the Old Galaha Road, and the river beyond. We also had two acres of land stretching from the Old Galaha Road down to the river. It was a rectangular block of flood prone, but very fertile, land. My mother, an industrious woman, had most of that land planted with varieties of banana. Our house stood on an elevated position looking down on the road.

Ivor Jennings, the Vice Chancellor, walked the length and breadth of the campus and the peripheral land acquired for the university on his early morning walks. Not every day, but often on weekends. The Old Galaha Road was one of his favourite walks. It was the road, in 1941, he took when he first visited the proposed university site.

The road started near Peradeniya Road and wound its way towards the river and then up the hill to the little clump of Balsa trees, just outside a bangalow which stood at the crest. The bungalow once belonged to Col. T Y Wright, owner of the Mahakanda Estate and who built the famed “Gal Bangalawa”, all of which were acquired for the university.

From the Balsa woods, down to our house was a distance of about 200 metres. Both sides of the road on that distance were grassland and shrubs. When one stood at the crest of the wooded hillock and looked down the road, all what one could see was the front veranda of our house and nothing else all the way up to Dr Mamooth’s house, the Persian veterinary surgeon attached to the Agriculture Department. The Old Galaha Road turned back to the left past Dr Mamooth’s house and joined up with the Galaha Road near the Post Office. And beyond the old post office was the railway station. Just near the level crossing were a couple of “Suruttu Kades” where one could purchase a handful of sweets for five cents or a Peacock cigarette for two cents.

Although we were given notice to quit, we had not found another suitable place to move to. The government had compensated us handsomely, well above the market value. It was a real bonanza, equivalent to winning the Gymkhana. But we had no place to move to; we wanted more time.

My mother, in typical Sri Lankan fashion, believed that if we asked the vice chancellor Jennings himself, he may grant an extension, which the powers that be had already refused. Jennings was the boss, and an Englishman to boot, and, my mother thought, he can bend the rules as he pleased. Although my father knew otherwise, mother stuck to her thinking and nagged father no end to go and see Jennings. My father gave many excuses, some probably fictitious. And so mother decided to get father to waylay Jennings on his morning walk.

It must have been a weekend. We were all at home. My father, being a school teacher, was also at home. In anticipation of Jennings coming down the Old Galaha Road, my mother got father to shave and change to a trouser and shirt from his usual weekend sarong and singlet and wait for Jennings to appear up on the crest near the Balsa woods. We all were on the veranda, watching. And eventually Jennings appeared, a typical Englishman with a walking stick in hand, briskly walking down the road.

Mother pressed my reluctant father out of the veranda to ambush Jennings. Without any enthusiasm my father started to amble down our driveway towards the road. The driveway was something like thirty metres. He had to synchronize his speed to match Jennings’ stride over a distance of about 150 metres. So, along the driveway, he inspected the cannas that grew on the side of the driveway, studied the emerging sprouts in a banana bush, timing his steps to intercept Jennings at the end of the driveway. He was perhaps working out the words for the encounter which he detested. But to keep the peace at home he had to suppress his loathing.

Jennings, of course, would have seen my father and guessed that the man coming down from the house was surely intending to accost him, to ask him something. Knowing Ceylonese, he would have guessed it would be some favour. Jennings also would have surmised that whatever it was, the man was hesitant about it.

My father reached the road when Jennings was about ten metres away. And before my father could open his mouth, Jennings pointing with his walking stick towards a bush on the side of the road behind my father and said, “You have some lovely birds around here!” My father turned around to look. There were a couple of birds visible but not exquisite by any means; so he searched for more. When my father turned back, Jennings was well past him and walking briskly away!

My father laughed all the way home to mother’s bewilderment. Of course he said something to my mother that Jennings would not engage and rebuffed his attempt to speak to him, although it was much later that father related exactly what transpired.

Jennings was not a trickster by any means. But he had an acute sense of the nature of Ceylonese and how to avoid tricky situations without offending. Jennings knew, if not exactly at least more generally, that my father was approaching to ask for a favour and which Jennings knew very well he cannot grant. Spontaneously he adapted a ruse to distract the pleader and to make his escape.

Soon after, we left Old Galaha Road to temporary accommodation in a vacant bungalow in the Peradeniya Estate on the way to Uda-Peradeniya.

A decade later I moved to Colombo and another decade or so later left Sri Lanka permanently. Nevertheless, Kandy was, and still is and always will be, home in more sense than mere residency. Yet, I never went back to Old Galaha Road to visit until just recently, some sixty five years later. And what havoc had visited on that wonderful place!

The place is unrecognisable from what it was in 1952. The Old Galaha Road (perhaps now with a new name) is still there. The beauty and the serenity of the place, what it used to be, have disappeared without leaving a trace of its past tranquillity. The greenery has been replaced with brick, mortar and concrete. The Balsa woods is no more. The shrubs, the meadows, the banana fronds, the cool breeze, the wild flowers, the butterflies and the birds, the sheer peacefulness of the place, all gone. Every inch of land was built upon with each building vying for a higher position in the ugliness scale.

Peradeniya University, in its initial phase in the early 1950s, had a unique architectural theme, not just in its buildings, but in landscape, in the flora, which mingled with the wider scenery of the place, the river and the hills. Its architecture was a blend of traditional and Kandyan coupled with modernity in space and light. Shirley D’Alwis designed it to perfection, perhaps taking a leaf from his mentor, Sir Patrick Abercrombie. Abercrombie was renowned for interest in maintaining the classic English rural environment in town planning. D’Alwis brought those concepts to Peradeniya, blending the built environment with Nature – just as it was done nearly 2,000 years ago at Sigiriya.

But that vision, the vision of both D’Alwis and Jennings, have now been almost totally obliterated. The Old Galaha Road is more a concrete jungle now than the serene university campus its designers envisaged. It was a depressing sight.

I walked further along the Old Galaha Road, retracing Sir Ivor Jennings’ early morning walk, and arrived at the first, and the oldest, university hall named after Sir Don Baron Jayatileke, the great educationalist, statesman and diplomat. There were “lankets” and sarongs and singlets strung across the balconies of the Jayatilake Hall for drying! The Galaha Road is a veritable street market with vendors plying their ware from plastic huts. Little remains of Jennings’ Cambridge dream and D’Alwis’s magnificent landscaping and architectural creation. What shame! This was an institution to produce intellectual elite, those of refinement, those who would lead the country. But all what it seemed to be producing is just uncouth youth who had crammed their way in, cram their way through, and leave with a piece of paper and sit behind a desk for the rest of his or her professional life. At least most end up thus.

The setting of Peradeniya, its halls of residence, its lecture theatres, its libraries and the playing fields, all give an indication of the thinking of its originator, Ivor Jennings. It was not just to be an institution to produce doctors, engineers, scientists, lawyers and historians; mere technocrats. It was meant to be a place to nurture intellectualism, to produce people of calibre, of moral and intellectual stature, to take up positions in the Academia and the higher echelons of the Civil Service, the Judiciary and the Legislature.

Jennings was not an elitist. His father was a carpenter and working class through and through for generations. Born to an impoverished family, he worked his way through scholarships to Cambridge, where he excelled first in mathematics and then in law, ending with first classes in both. His politics was that of a left leaning liberal, a Fabian and a friend and colleague of Harold Laksi at the London School of Economics. Thus, it was not his objective, one can surmise, to build a university for the sons and daughters of the rich. Jennings wanted to guide the cream of the cream of Ceylon, irrespective of social strata, to the leadership of the country. But what do we have now, in parliament, in the judiciary, in the civil service?

Jennings envisaged a great university at Peradeniya. But it is now (at the time of writing) at 2,000 or below in most world rankings whereas Cambridge is above 10, and often at the top in some rankings. As if to add insult to injury, there is a statue of Sir Ivor Jennings recently erected at Peradeniya. If he, Jennings, could see the Peradeniya campus now and the quality of its graduates, would he be proud to stand on that pedestal? I doubt.

Perhaps the sculptor should have sculpted tears flowing down Jennings’ eyes to depict the tragedy of a failed mission!

Farewell: Jennings bids adieu to Pera Uni by walking its breadth

Farewell: Jennings bids adieu to Pera Uni by walking its breadth

TWO: G. H. Peiris = Recollections from both Peradeniya and Cambridge

I read this piece with a great deal of interest and could comment on its as the oldest living authority (!) who for well over 64 years never severed connections with the university and the remnants of the Jennings’ legacy.

The basis of my claim is that I lived in a locality that was engulfed by the University of Ceylon since early 1947 (the year of the ‘Great Floods’) in what was then the hostel where the Kingswood Primary School boarders were lodged. I remember how, on Sunday evenings, we were made to line up two-by-two and led along a cart-track through Rajawatta (‘King’s Garden’ –a pre-colonial name, surely– which became the residential venue of “minor employees” of the university) to that little pond and the summer house (two structures that have survived), from where we were able to see parts of the lower valley being cleared and levelled for the impending infrastructure. Our hostel came to be occupied a few years later by the Dental Faculty (one of the two oldest university institutions to begin courses of study at Peradeniya).

What Varman says about the ‘displacement’ of his family sounds truthful in the sense that the 800 acres which the government made available to establish the national university must have involved a few evictions. But the government appears to have been quite generous towards those evicted. Kingswood College (i.e. Methodist Church) was compensated with a forty-acre block of land with quite a grand building named ‘Nandana Māligāva‘ (lit. ‘pleasant palace’) adjacent to the Colombo highway (who built that, and for what purpose – it was certainly not the residence of a plantation sahibs), now being used as the venue of a Theological College. Varma also says: “The government had compensated us handsomely, well above the market value. It was a real bonanza, equivalent to winning the Gymkhana”.

Almost the whole of the Peradeniya campus site at the advent of Sir Ivor — a square-mile of territory – included a golf link, an abandoned sugar plantation (one of the earliest to be established in the island), and an abandoned rubber plantation on the Hantana lower hill-slopes. The ‘Gal Bangalava’ (a periya dorai residence) to which Varman refers, represented another massive donation to the university, one that involved about 1,800 acres of land which has remained criminally underutilised. Did those at the vanguard of the University of Ceylon project have in mind a twin campus at full development?

[To digress, in order to impress upon those concerned about our university and the gigantic resource waste that has been going on, why did the university decide, years later, to locate the livestock field station for the Faculty of Agriculture at Mawela 2 km well beyond the ‘Upper Hantana’ locality (instead of the land available at Mahakanda), shift to Dodangolla (20 km away from the university) in the early 1970s, and then, finding that site unsuitable for undergrad teaching, develop livestock facilities within the main campus at enormous cost]

It is not at all surprising that Jennings was quite brusque at his encounter with Varman’s father. He must have experienced the type of totally unfair pleading which our people sometimes make. Though Jennings was stiff and formal even in his social interactions with his colleagues at Cambridge (he was a regular at my guru B. H. Farmer’s annual ‘Sherry Parties’), he had an abundance of affection and esteem for ‘Ceylon’. Despite the burden of duties as VC of that university in the early 1960s, he seldom missed a meeting of our tiny ‘Ceylon Society’. At another memorable meeting – the Matriculation Ceremony’ for all new entrants to post-graduate courses – addressing an audience of about 300 from all over the world, with the bulk being graduates of Indian universities, he said that Cambridge requires all matriculates to formally obtain ‘Tripos’ qualifications as stipulated by their departments before they are admitted to doctoral or masters programmes, but exceptions are made for the graduates of the University of Ceylon and certain universities in Canada and Australia. This evoked a howl of displeasure and protest, with Sir Ivor standing firm about the Cambridge requirement. In his response he referred specifically to the University of Ceylon and said: “We are certain about the quality of the degrees it awards”.

I have brought Sir Ivor at Cambridge into my narrative in order to show that there is much substance in Varman’s lamentation on the status we have lost in the world of higher learning. BUT, Sir Ivor should share at least marginally the blame for that loss. It is quite amazing that a scholar and intellectual of his calibre failed to see that, except in ‘traditional’ architectural and landscape embellishments, an Oxbridge model could not have survived for long in the Sri Lankan setting.

Sir Ivor’s mission was not confined to embellishments. I think it was Sir Ivor’s scholarly stature, more than all else, that attracted a galaxy of British scholars –Joseph Needham, Edmond Leach, John Kenneth Galbraith, Gunnar Myrdal, Nicholas Kaldor, Joan Robinson, Ursula Hicks, John Hicks and Oskar Lange (all, except the ‘Harvard economist’ Galbraith, were from Cambridge)– to devote their benign attention to the affairs of the ‘model’ colony.

In my understanding, post-war Cambridge and Oxford produced an intellectual and professional ‘elite’ mainly from the academically gifted pre-university students whose background spanned a wide spectrum of social classes (and not confined to those of the higher strata of society as it had been in earlier times). In the ‘Royal’ declaration of “University of Ceylon More Open than Usual”, what was envisaged was a perpetuation the ‘Oxbridge model’. How on earth could that have been a reality!

The empirical basis for “my understandings” is too well known for me to specify in this already excessively long comment. I have, in fact done that in a volume which I co-edited with K. M. de Silva: The University System of Sri Lanka: Vision and Reality, Delhi: Macmillan, 1995.