Kulturs And O’facs of Peradeniya. Remnants of Colonial English.

Source:Island

A passing social structure found in the Peradeniya of the 1950s, was the Kulturs and the OFacs which had much to do with English being the social residence of some of Colombo society in immediate post-colonial times.

Old Ceylon it was that gave the island some of the best and enduring about the human condition, and they were works in Sinhala. Martin Wickreamsinghe’s Changing Village, or Gamperaliya and Sarachandra’s and Peradeniya’s Maname, to mention only two, for economy.

Quite apart from the novel, Gam Peraliya it was, when Ceylon in 1948 introduced free education. This changed significantly life and opportunity for the young of rural Ceylon. At university level it showed in the large number of students entering in the 1950s, with Sinhala as their natural language of living. The Colombo and other urban city schools sent in students for whom English was their long colonial inherited mother tongue. In the country at large, urban English speaking people and Sinhala speaking rural ones lived separate lives. But concentrated together in a residential location like Peradeniya, consciousness of each other became noticeable.

Before going into this cultural division, it is necessary to say a little about the English language, because the Kultur-Ofac divide had much to do with English in immediate post colonial times being the sustenance of one, and an unknown, to the other.

Sinhalese and Tamils, before the ethnic issue was pushed in by the middle classes of Ceylon in 1956, were not a social divide because they were geographically divided, anyway. They occupied separate parts of the island, Sinhalese in the south, central and northern areas below the Jaffna peninsula. Tamils in the north and east.

Those Tamils who had been attracted by what the capital city of Colombo had to offer materially, were not of consequence in numbers before 1905. In 1905 when the first railway train service from Kankesanthurai to Colombo was begun the numbers increased, of Tamils who wanted to make Colombo their life.

Like the Sinhalese middle classes of Colombo, they became westernised, sent their children to schools such as Royal College, St. Thomas’, Ladies and Bishop’s Colleges. English became these Tamil’s language of communication and thought, like the westernised Sinhalese. The use of the native languages amongst these colonised classes was sparing and colloquial, with domestic servants and street vendors who came to the door.

The significant result was that class submerged race or ethnicity with the westernised Sinhalese and Tamils of Colombo. When many Sinhalese of Colombo protected Tamils during the much later ethnic killings, they were protections of their class. The protected Tamils were not of the classes like Tamil used bottle/newspaper collectors who came down the road. Not deliberate but social circumstance.

While culture was inconsequential and seemed to be one and the same amongst Colombo’s westernized Sinhalese and Tamils, in the large rural areas of Ceylon it was very different. Especially as this poorer majority could not benefit from school education which had to be purchased before 1948. Theirs were Sinhala and Tamil derived cultures.

In ancient times whatever reading and writing they had was from Buddhist and Hindu temples, which had thousands of years of being the only places where reading and writing could be learnt. And this temple offering was not entirely religious. It was secular as well , though limited. And before the first Christian missionaries started schools that taught English, such as Richmond College Galle in 1876, there were limited rural schools teaching only in Sinhala.

Piyadasa Sirisena born 1875 and died 1945 is relevant. There are three schools that he took his early education which were Warahena school, Induruwa, Bentara school of Bentota and Brohier’s school at Aluthgama, a missionary school where he learned basic English. He could not use English for literary creations. He is widely considered the father of the Sinhala novel, though it is the opinion of scholars that they were more like Buddhist sermons. He was the most popular novelist of the era. Suggestions that the form of the novel was not entirely a British colonial importation.

In 1948 Education Minister C.W.W. Kannangara introduced free education island-wide which eventually produced a class of people, mainly rural, who were cultured through their native languages, not through English, though some English began to be taught in the island-wide free education.

To be apparently a little desultory, a brief reference to the history of English:

That English came to Lanka through being colonized had social relevance at that time, but today has lost that significance because it has become a world language through the historical fact of the European “finding” and British founding of the United States of America, the world impact of which spread the language both for physical science and social sciences as well as world trade and political communication between nation states.

English originating from Germanic tribes which brought it to Britain, was like all languages progressively invented. English has acquired a tempting comparison to maths in its universality and its independence from cultures. But Mathematics, did not originate in any culture but was in nature before human existence. Humans discovered its existence.

Einstein’s E = mc2 is the world’s most famous equation, Energy equals mass times the speed of light squared. On the most basic level, the equation says that energy and mass (matter) are interchangeable; they are different forms of the same thing. This physical relationship existed in nature

before Einstein, before any human. What Einstein did was to discover what existed and give it a formal equation. The spiral arrangements of leaves on a stem, and the number of petals, and spirals in flower heads during the development of most plants, represent successive numbers in the famous series discovered in the 13th century by the Italian mathematician Fibonacci, in which each number is the sum of the previous.

English cannot aspire to this ‘no culture’ universality because it is manmade, not discovered in nature. So, it unlike maths, will show cultural variation. However, this will not be significant enough to become separate languages in different cultures.

Free education in Sri Lanka made English possible, even though very limited, across social strata, but it took time before the Colombo school class realized that the English- based “Kulturs” was a passing phenomenon of “culture” closely associated with English of colonial association..

The origin of the expression “Kultur” may be vaguely associated with the German expression “Kultur Kampf”, or generally associated with those who were supposed to be cultured. The origin of its use in Peradeniya is from the Colombo schools. Certainly, the utterance of the term in the Peradeniya of the mid-1950s was amongst the Colombo school-undergrads. The undergrads of the Oriental Faculty were not as involved in this classification as the other “Kampf”.

Whatever social phenomena appearing in Peradeniya had to have their base and origin in the country outside.

There is a story about the opening of Maname in November 1956 at the Lionel Wendt theatre in Colombo, that suggests “Kultur” and “Ofac” were brought into Peradeniya by a segment of Colombo. The extract is from “Maname In Retrospect” by Professor K.N.O. Dharmadasa, in The Island newspaper, of June 5, 2013.

“As far as popular taste of the day was concerned the Sinhala theatre was an art form in the periphery, no one being prepared to buy a ticket for a performance except as a matter of charity. This, the university students learnt, when they tried to walk to houses in the environs of the Lionel Wendt Theatre on the four days, they stayed during the time of first performance.

“Sarachchandra himself recounted in his autobiographical Pin Eti Sarasavi Waramak Denne an incident he faced on the second or the third night. He was seated in the foyer while the play was in progress and all of a sudden, a limousine came to a halt at the entrance and a well-dressed woman walked in. She asked “What is being staged here today?” and being told that it was a Sinhala play wanted to know when it was going to be over.

When Sarchchandra told her that it would be over in two hours she was not prepared to believe him. “What! A Sinhala play being over in two hours? I am sure it will go on till about 9 or 10pm” Then Sarchchandra told her that he was pretty sure of the duration of the play and if she was keen to see it, she could get in without any payment and leave whenever she wanted.

The lady looked disdainfully at Sarchchandra and declared “Shih! I don’t want to see these Sinhala plays. I only wanted to send my servant woman and she cannot be allowed to waste three four hours here” and walked away.”

Three much repeated fictions constructed by the Kulturs, indicates that it was English that divided the two groups.

One Dr, Andipala a lecturer in Oriental culture , on board ship as he was on his way to London, had an old Englishman sit by his side on deck. The Englishmen complained, ” I’m aching from Arthritis”. Andipala responded, ” Hello, I am Andipala from Sabaragamua”.

The same Dr. Andipala was given a lift by Mrs. Doric de Souza on the way to a lecture. When he was dropped at his destination, he said “Thank you”. She responded in her western orientation, customarily ” Don’t mention”. In this made-up story of the kulturs, Andipala put his face close to the window glass , and said, blushing, ” You also don’t mention”.

Ramanathan Hall, the tallest of the residential halls, was the only one with a lift. A kultur fiction of the time was that Andipala on his first visit to his hall remarked, ambiguously,

“I was highly taken up by the lift.” The kulturs did not give him the benefit of the doubt.

In the meantime, Maname gathered momentum, largely unknown to the kulturs, though happening in their times and in the same territory.

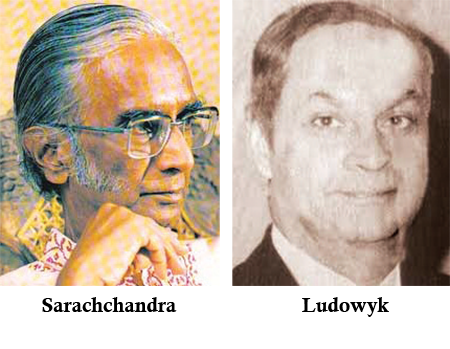

Undoubtedly, there were segments that cut across this mental and social divide, both amongst students and lecturers. Ludowyk and Sarachchandra need mention here. Ludowyk, a Burgher developed a deep and worthwhile interest in the culture of the Sinhalese. He studied Sinhala at the Buddhist temple in Kandy. He had much interaction with Sarachchandra about Sinhala theatre, and encouraged the first translations of Gogol, Moliere, and Wilde by Sarachandra, and has left us evidence of his attempt at integrative search, in his book ” The Footprint of The Buddha”, about the culture of Ceylon, Buddhism and its teachings. Sarachchandra records all this in his Ludowyk memorial lecture in 1989.

Sarachchandra, in this context, complements Ludowyk. While his search for foundation was his sought-after Sinhala and South Asian culture, after a British colonial childhood, like Rabindranath Tagore, he did not see all the results of the colonial experience as destructive and discardable. The British colonization of Ceylon also happened to provide Lanka’s first major contact with the best of Europe.

He saw his Sinhala culture as part of the common human story, so he identified the best of the European culture, as intergrative with the Sinhalese as part of humanity. And he was not for blind imitation of the West or for the mere revival of Sinhala tradition. Under these circumstances the need was to select and synthesise what aspects of Sinhala tradition were to be revived and how, because traditional art forms arose within a specific social and political milieu and mere revival had little significance against a modern backdrop.

How was a synthesis to be achieved so that the “foreign” would no longer be “alien”, and the traditional Sinhala culture no longer historical? He utilized tradition to create new works of art. Hence the need for new creations where the essence of tradition, relevant to our times was retained, and integrated with relevant world human culture. Maname (1956) is a modern work of art based on Sinhala tradition fusing with culture common to humanity.

That kultur of the mid-fifties was a fading smudge in Peradeniya, while Ofac was a growing creative force, was evidenced by the growth of Maname. This play though coming off the creative imagination of Sarachchandra, would not have been possible without the enthusiasm for its promise, of the creative students of the Oriental Faculty, organising for it and providing their talents in singing, dancing and conveying their dramatic feelings to audiences. Peradeniya University is now nearly 70 years, and it is unlikely that in its contributions to the country, Maname can be rivalled.

A look, sometimes desultory, at Kultur and Ofac, a passing social phenomenon, based on a superficial relationship with English by a small number, feeling elite, in those days of Peradeniya.