Lowering the brow : The films of H.D. Premaratne-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

The face of Sri Lankan films changed in the 1970s. This was due to a number of reasons. Arguably, the most important of them would be the rise of the Sinhala Buddhist rural petty bourgeoisie. Initially represented as side characters, they eventually became protagonists and antagonists in the films which featured them. Lester James Peries’s Golu Hadawatha and Akkara Paha broke ground, in that sense, by casting this milieu in films that not only performed well at the box-office, but also won awards, internationally.

These were decades of expansion in the university system and the public sector. The SLFP’s historic win in 1956 had secured for the Sinhala middle-class a place in the sun: that spilt over to the country’s cultural and social landscape. It was in this interregnum, between the Bandaranaike and the Jayewardene years, that pulp fiction became established in Sri Lanka, despite the opposition and resistance it provoked from the establishment. After Gunadasa Amarasekara and Siri Gunasinghe, the likes of Karunasena Jayalath gained a foothold. These developments and shifts soon extended to other art forms.

Thus it was in this interval, between the social transformation of the Bandaranaike years and the liberalisation of the cultural industries in the Jayewardene years – two processes which liberated and contributed to a decline in artistic and cultural activity – that I locate H. D. Premaratne. Together with Vasantha Obeyesekere, Premaratne redrew the frontiers of artistic and commercial cinema. This rift had emerged with the films of Lester Peries: while applauded by critics, they very often failed at the box-office. No mass culture / high culture dichotomy had prevailed before: Sinhala films, from their inception in 1947, were made to please popular audiences. Peries’s films thus heralded a radical shift in the way Sri Lankans viewed and thought about the cinema. Dharmasena Pathiraja, a critic of Peries’s work, tried, a generation later, to realise the political potential of the medium.

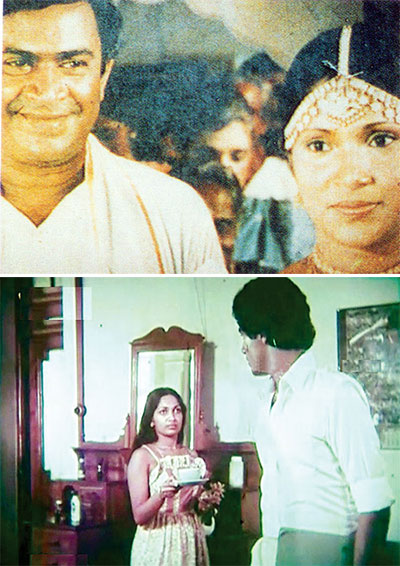

H. D. Premaratne emerged at this juncture. Having worked as an assistant, he made his first film, Sikuruliya (1975), around the time Pathiraja was making Ahas Gawwa. The second or so film to be shot in Cinemascope, Sikuruliya tried to achieve some kind of a compromise or balance between the demands of popular and commercial cinema. If Premaratne was, in his later years, conferred with the title of the father of the middle cinema in Sri Lanka, it is not because other directors didn’t try to chart middle ground in the Sinhala film, but because no other director succeeded in that endeavour the way he did. Sikuruliya, in that respect, is the spiritual successor to works like Dahasak Sithuvili and Hanthane Kathawa, which combined song and dance sequences with a simple naturalism of style. But the directors of these films did not replicate their initial successes. Premaratne did, again and again.

In Apeksha (1978), Premaratne tried to combine a conventional romance with class politics. There is a scene where the protagonist, played by Amarasiri Kalansooriya, poses as the rich paramour of Malini Fonseka to her father, played by the stern Felix Premawardhana. The sequence where Kalansooriya is revealed as an imposter, and then kicked out of the house, reveals the director’s class sympathies very clearly. Yet what is fascinating about Apeksha is not its class politics, but rather the way the director enmeshes them with tropes borrowed from the mainstream cinema: the hero/villain dichotomy, the triumph of good over evil, the final fight between hero and villain, and the reconciliation of the woman to the man, and the man to the father of his lover. These were years of unrest, and in depicting the conflict between rich and poor, Premaratne tries to capture that unrest.

To be sure, Premaratne does not entirely succeed in his enterprise. This is to be expected: the limitations imposed by the popular cinema tend to cripple any attempt at a political statement. Here it is interesting to compare Premaratne’s film with what his contemporary Vasantha Obeyesekere was doing at the time. Apeksha came a year before Palangetiyo, which, after Dadayama (1984), goes down as Obeyesekere’s finest work. In Palagetiyo, the director employs the tropes of the commercial cinema in several fantasy sequences: the protagonist, played by Dhammi Fonseka, is addicted to romantic fiction, and imagines a life of ease and comfort with her lover, who works under her father. By contrast, Diyamanthi (1976), also by Obeyesekere, depicts a group of teenagers who while away the time, make friends with a rich heiress (Malini Fonseka), and unravel a diamond heist.

There is a sequence in Diyamanthi which reveals the director’s attitude to the politics of rebellion: the protagonist, played by Vijaya Kumaratunga, is evicted by his landlady, played by Rathnavali Kekunawela. He is without a job. Given his credentials – he has a Bachelor of Arts, a qualification associated then as now with lack of employability – he faces a bleak future. Yet what Kumaratunga’s character does is to take his Bachelor of Arts and toss it into a trashcan nearby. Here Obeyesekere epitomises the freewheeling optimism of the youth, yet also sidesteps their growing frustrations. The contrasts with Palangetiyo and Dadayama are very clear: while Diyamanthi remains hopeful about the future, these two films suggest optimism, only to subvert it. Dadayama, in particular, has its heroine dream about marriage life with her lover, only for her to fall into one calamity after another.

Obeyesekere’s politics were centre left; Pathiraja’s were radically left. Obeyesekere’s later slide down into obscurantism, epitomised by Maruthaya (1995), pushed him away from the politics of middle period films like Dadayama and Kadapathaka Chaya (1989). Premaratne, in comparison, became increasingly commercialist in his outlook, though this did not cripple his attempts at achieving a fusion between the popular and the artistic. This fusion does not always result in artistic works: too often the commercial, mainstream aspects of his stories prevail over their political orientation. A good example here would be Parithyagaya (1980). On the surface, it’s an indictment of a cultural practice, the diga or the dowry system, which penalises poor families searching for a suitor for their daughter. The theme is handled well, and at the end, when the police come to arrest the protagonist, who robbed a store to raise money for his sister’s wedding, we feel the injustice of it all acutely.

Yet Premaratne’s concern for the downtrodden underlies a somewhat regressive outlook. In her critique of Parithgayaga (“’Parithyagaya’ – Who sacrifices what and for whom?’, Lanka Guardian, August 15, 1988, 24), Sunila Abeysekera argues that the protagonists of the story do not actively protest the dowry system, but rather acquiesce in its workings. The heroine’s brother does not question the dowry; rather, he goes on to raise it himself. The heroine’s suitor, a schoolmaster played by Tony Ranasinghe, also sidesteps the wider implications of the diga system: he merely suggests that his family want the best for him, and it would be unfair by them to ignore what they want for him. The characters who pass for villains in the story – the schoolmaster’s mother particularly – are caricatured, yet this caricaturing fails to overcome “the silent and passive acquiescence” of their victims.

I would, of course, take such critiques with a pinch of salt: as Sumitra Peries has told me regarding criticism of her own films, critics tend to assume that characters in a particular situation and context should behave in this way or that, without realising that the conditions of their existence push them to accept practices which contemporary society may consider traditionalist, regressive. But Abeysekera’s criticism should not be sidestepped either, if at all because it reveals the limits of Premaratne’s beliefs. For me those limits are epitomised, more than any other work, by Deveni Gamana (1982) and Visidela (1997): the first offers a critique of the practice of checking a woman’s virginity on her first night, the latter presents a troubled village at the time of the second JVP insurrection. Both are overwhelmed by the tropes of popular films: the woman in Deveni Gamana, rejected by her lover and his family, returns to him, while the hero of Visidela kills the man who raped his sister.

Nevertheless, Premaratne’s achievements cannot be ignored. Like Roger Corman, he never lost a cent on his films. Unlike Vasantha Obeyesekere, he did not slide into obscurantism: this is as much a testament to his artistic outlook as it is to the limitations of his politics. I think he overreached himself in his last work, Kinihiriya Mal (2001), which combines rather well a critique of Free Trade Zones and of an economic system which condemns women to prostitution, but then upends it all by drawing stereotypes of a “good” village girl (Vasanthi Chathurani) and a “bad” city girl (Sangeetha Weeraratne). “Reality,” Malinda Seneviratne wrote in his (mostly negative) review of the film, “isn’t so stark.” Perhaps not so in real life. But the reality that Premaratne occupied was different, markedly. Again, that is a testament to his outlook, as much as it is to the limitations of that outlook.

(The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com)