Lunuganga: Bawa’s homage to nature- By Sarah Souli

Source:Sundayobserver

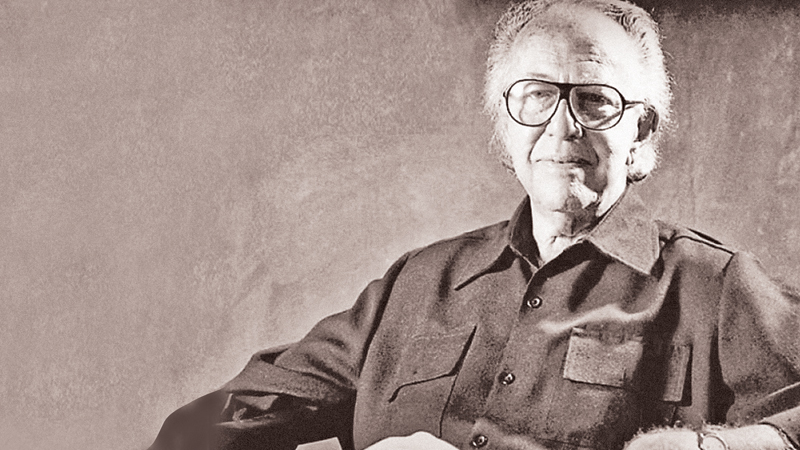

From the outside, the Colombo house of Geoffrey Bawa, the late Sri Lankan architect and pioneer of tropical modernism, does not command much attention.

Bleary-eyed from our long-haul flight, my friend Maia and I nearly walked past the white, cube-shaped building, which is partially obscured by trees. But we were soon warmly greeted by an attendant, who slid open a mahogany door to reveal a garage, complete with Bawa’s 1934 Rolls-Royce.

We slipped off our shoes and began speaking in hushed tones: even Bawa’s garage called for a temple-like reverence.

No.11, named after its address on Bagatalle Road, is in the gentle Kollupitiya district. It’s open to the public for tours; a two-bedroom suite — Bawa’s guest room — is also available for overnight stays for design devotees like me.

The room was still occupied when we arrived, so we padded down a white corridor, the eggshell paint reflecting sunlight and creating a mini hall of mirrors. At the end, a sitting room looked out to a small garden that lulled us with the sounds of rustling palms and trickling water.

Bawa, who died in 2003, believed in bringing the outdoors in, blurring the line between these two realms.

In the more than 40 buildings he designed in Sri Lanka from 1948 until 1998, he made certain that they were built in harmony with the surrounding landscape.

Bawa studied law and travelled the world before becoming the country’s most celebrated architect. He married traditional Sri Lankan architecture with the more formal qualities of European modernism to create a style that remains popular today.

His sun-mottled courtyards, shaded verandas, and vaulted ceilings are perfectly suited to the country’s tropical climate.

Sri Lanka, a teardrop in the Indian Ocean, is one of the most biodiverse places in the world, dotted with lush jungles, grasslands, forests, and savannas. Bawa’s buildings are a love letter to it all.

“He completely acknowledged the environment in which he lived — the nature, the climate,” said Channa Daswatte, a leading Sri Lankan architect who trained under Bawa. Today he heads the Geoffrey Bawa and Lunuganga Trusts, which manage his buildings and set up tours of his works.

Daswatte had invited us to his own home in the suburbs of Colombo, where we sipped gin and tonics in an airy living room. He is an established architect in his own right, yet we could feel Bawa’s influence.

The house pays homage to the local architecture, and indigenous materials and the work of regional artists are featured prominently. My personal favorite was the large block print that hung over his bed.

Homage

After a few days in Colombo visiting other important Bawa buildings including the nearby Sri Lankan Parliament, a group of copper-roofed pavilions that seems to float on a man-made lake, we headed two hours south to Lunuganga, Bawa’s country retreat, which is tucked into the hills of a former rubber plantation.

Bawa bought the 19-acre lakeside estate in 1948 — the year that Sri Lanka, then known as Ceylon, gained independence from British rule. He spent years transforming the colonial-era building into his dream home, creating courtyards and water gardens, planting frangipani trees, and adding Roman-inspired sculptures.

He literally moved mountains, shaving the top off a hill so he could have clear views of the lake while enjoying his morning coffee on the terrace. Lunuganga also acted as an incubator where Bawa could try out architectural motifs and designs for objects such as gongs and bells, which were positioned around the property to call for lunch or afternoon tea.

Today, Lunuganga has nine guest rooms, including No. 5 or, as it’s more casually referred to, Ena’s house. One of Bawa’s longtime collaborators, Ena de Silva was an artist who is credited with single-handedly revitalising the country’s batik industry.

The Ena de Silva house was originally built in Colombo in 1962. Its main feature — a central courtyard that is entered, delightfully, through a “singing” door made entirely of bells — was seen at the time as a radical design element for an urban home. When the house was slated for demolition in 2009, the Lunuganga Trust moved the structure and rebuilt it, piece by piece.

Lunuganga is near Bentota, a small beach town that contains a tourist complex Bawa was commissioned to design in the late 1960s. It has a main shopping centre, a town square, and two hotels.

One of them, the 159-room resort today known as the Cinnamon Bentota Beach, was renovated three years ago by Daswatte and his firm. Its most striking detail is the replica of the original ceiling in the reception area: a kaleidoscopic collection of batik panels designed by de Silva. Nearby, we visited the train station — one of the rare public works Bawa designed — a green-and-yellow-trimmed building with a terra-cotta roof and windows that resemble portholes.

Beruwala

The next morning we drove about half an hour to Beruwala, where we strolled through Brief Garden, the work of Bawa’s older brother, Bevis — a renowned landscape architect. Five acres of lush gardens feature walking paths, fountains, and homoerotic sculptures.

Our next stop was Galle, an ancient port and the location of Bawa’s Jetwing Lighthouse Hotel. Its cylindrical entrance has a winding staircase that ascends from a pool of water to the top of the building. Looking up to the roof from the lobby felt like standing at the bottom of a well.

The coast was soon hit with thunderous storms, so we decided to move inland to the Cultural Triangle, a holy area also known as Rajarata. The jungle-filled region is packed with archaeological wonders, including the cave temples of Dambulla and the majestic Sigiriya rock palace. It’s also home to Bawa’s Kandalama. Completed in 1994, this Brutalist-style property, now known as the Heritance Kandalama, is nestled into a series of rock formations and almost looks like an extension of the mountain.

From our tree-house-like room we looked out to the dense forest. Bawa envisioned that Kandalama, at some point in the future, would be completely overtaken by its lush surroundings, and nearly 30 years on, the property is almost entirely sheathed in greenery. Before Covid-19 and Sri Lanka’s recent political and economic crisis, architecture fans would book rooms in Kandalama years in advance.

But on our trip, only half the rooms were occupied. That night we fell asleep to the patter of rain and awoke to monkeys knocking on our windows, clamouring for snacks. To stay at Kandalama was to see Bawa’s dream realised: canopies of vines crawl over the steel beams, bats nest in the corridors, and, at any given time, there are more monkeys than human guests — a fitting coda for an architect who always believed in nature first.

– Travel and Leisure