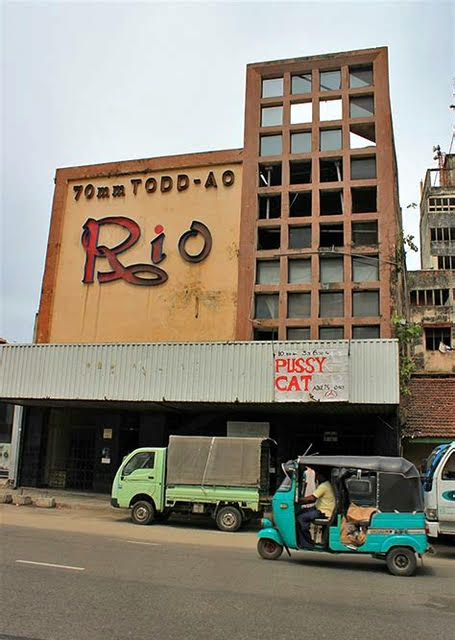

Navaratnam of Navah and Rio theatres – by Smriti Daniel

Photo source: CinemaTreasures

Rio Cinema Slave Island Opening Day ! It’s hard to believe this complex was once amongst the area’s best known landmarks. When the Rio opened its doors in 1965, it was to offer Sri Lankans their first sight of a 70mm TODD-AO projection system. In the audience on the opening night was a man only a month away from his fourth – and longest – stint as Prime Minister (Dudley Senanayake) and a young girl who would go on to become Sri Lanka’s President (Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga), 29 years later.

This Mr Navaratnam’s son is the man I meet, in a room behind the box office downstairs. His name is Ratnarajah Navaratnam, known to all as Thambi (meaning little brother, as he was the youngest of his siblings) and he was in Colombo in the July of 1983. His parents Navaratnam and Rukmani were in India, and he is glad they were not here when the mob came. He tells me his is a family with respectable antecedents. (On his mother’s side, his great-grandfather Sangarapillai was the founder of the Manipay Hindu College in Jaffna.) But his parents themselves were not rich to begin with. Thambi’s father, Navaratnam, lost his own father very young. His father had been a soldier in the British army and, when he died, Navaratnam was forced to leave school to support his family. He began to work in Colombo with his uncle Thambyah, the successful owner of the city’s first colour printing press. Navaratnam was by all accounts a remarkably enterprising and hardworking man. He made a success of the business, multiplied his investments and raised loans until he was able to build the Navah Cinema, whose construction he oversaw himself, without the help of an architect. It was a process he would repeat with both the Rio Cinema and Hotel.

>

> Navaratnam eventually became so experienced that he could, by instinct alone, instruct the builders on the proportions of sand, cement and water that had to go into the concrete mix. On nights when the builders worked all night, he stayed with them till sunrise.

>

> His children remember their father as pious and stern – “a traditional Jaffna father” – but being the sons of a successful cinema owner had its benefits. People affectionately dubbed the Rio the R-10, and for a while that was also what Thambi’s friends called him. He would write them little notes guaranteeing them free entrance into the theatre, but never so many that his father would notice.

>

> If Navaratnam had an obvious soft spot, it was for the surrounding area. In English it is known as Slave Island, a name that many signboards still carry. But in Sinhala and Tamil it is Kompannaveediya/Kompani Theru or Company Street. The Beira Lake once encircled this space completely, and it was home to African slaves of the Dutch and Portuguese colonisers. Later it became a hub for traders and businesses and, to date, remains a pocket of incredible diversity within the city. Temples, churches and mosques are separated by the narrowest of streets, and the neighbourhood is thick with Sri Lankan Moor, Malay, Tamil and Sinhalese families, with the odd Dutch Burgher in the mix. (It is one of the few places in town you can buy an authentic Malay pastol, a traditional pastry stuffed with meat.) Growing up, Thambi remembers his father’s deep emotional investment in the surrounding communities. It was a rare cause to which Navaratnam did not generously contribute, he says, and he was even-handed with people of every faith. His car was always available on loan to locals when they needed it for a celebration or a funeral. According to Thambi, when the family asked him to move to a more genteel part of town, his father always refused. “He would tell us, ‘This is the area I grew up in, this is the area that I support, this is the area that I stand by and this is the area I want to grow old in.’” Premadasa’s is the Rio’s oldest employee, and though he now works at another cinema in the city, he still has a space to live on the premises with his family. Premadasa’s home is accessible through the parking garage at the Rio. He is, as he always was, the consummate odd job man. He can turn his hand to many things, from running the box office to cleaning the popcorn machine, even managing basic accounts when called upon.

>

> Premadasa’s assessment of Navaratnam is quite similar to that of Navaratnam’s children – that he was strict but fair. Now 63, Premadasa was a young man when he first entered Navaratnam’s service, earning some five rupees a day for the film posters he would paste in various parts of the city. He was soon promoted to being a hall attendant, responsible for seating 600 people at a time. He remembers the Rio was among the most successful cinemas in the city – many shows were sold out, even the balcony where a ticket cost Rs 3.20. Black July, as it would later be known, is taken to mark the beginning of a civil war between Tamil militants and the government of Sri Lanka that lasted nearly 30 years. It also drove an exodus, as a great number of Tamils left Sri Lanka for the shores of other countries.

>

> Premadasa remembers old Mr. Navaratnam’s return from India a few days later: on seeing what had happened to his life’s work, he broke down and cried bitterly. Soon after that, he fell ill.

>

> In 1984, the family emigrated to Australia. Navaratnam never returned to Kompannaveediya or to Sri Lanka. As he lay dying, Thambi says his father seemed immensely vulnerable. So distant before, he would now ask his children to sit by his side and simply hold his hand.

>

> On the day of the riot, Premadasa was on the property. He recalls that the rioters who came to the Rio were a mixed group, of people The mob was intent on stripping the property bare: they spent much of the day robbing the luxurious hotel of its furnishings and equipment and then, around sundown, set what remained on fire. Published on Commonwealth Writers on July 15, 2015.

Words by Smriti Daniel.

—————————

The following is from Chris Lawton

Passing though Slave Island I have often wondered what had become of The Rio 70mm Cinema . It certainly was a spacious and comfortable theatre comparable to the Savoy. Some beautiful musical films were screened there and tickets even to the Balcony seats had to be booked days ahead.

I recall an amusing incident which occurred to me one evening when I took my family to see the 6.30pm musical show “ South Pacific “ ( if I remember correctly ) in the early 1970s. As the car park was full I had dropped my wife and children at the entrance and then parked my car at a small vacant lot by the Polski Hotel across. When I went to pick my car up after the show I noticed that all four wheel hub caps were missing ! I saw a young teenage boy loitering around and asked him if he had seen anyone near my car . He was quick to reply “ No,Sir “ ! He said so with a sly smile and then added that he could quickly find out and get them for me for a small reward of Rs.10. !! He did this very promptly. I later understood that I was not the only victim of this scam. The urchins from the nearby tenements of this business suburb were quite enterprising indeed !