Oral cancer: Essentials for the Dental Practitioner – By Professor Saman Warnakulasuriya

Source: Newsletter of the College of General Dental Practitioners of Sri Lanka

Oral cancer remains an important public health problem, in Sri Lanka and in many south Asian Countries. The disease affects both men and women and all racial groups. The mean age at presentation is around 60 years but oral and oropharyngeal cancers are now becoming more common in younger ages. Oral cancer is predominantly found among tobacco users, betel-quid chewers and people who drink alcohol to an excess (1). It is estimated that around 75% of oral cancer deaths are due to risky lifestyle habits. A proportion of oral cancers are preceded by potentially malignant disorders (earlier referred to as precancerous lesions and conditions). These include oral leukoplakia, erythroplakia, lichen planus and oral submucous fibrosis (2).

A proportion of oral cancers are preceded by potentially malignant disorders (earlier referred to as precancerous lesions and conditions). These include oral leukoplakia, erythroplakia, lichen planus and oral submucous fibrosis (2).

Oral cancer can affect the lip, oral cavity or the oropharynx. Lip cancer is a distinct entity, is rare in dark-skinned populations and is mostly caused by exposure to UV sunlight among people not protected by the melanin pigment. Oropharyngeal cancer is now considered a separate entity as it is primarily caused by certain high-risk types (eg. types 16 & 18) of the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Clinical aspects

Oral cancer has multiple forms of presentation, and this sometimes makes the disease difficult to recognize, especially in its early stages (3). This article describes the clinical manifestations of oral cancer and its differential diagnosis to help the practitioner to differentiate the early forms from other (non-cancerous) disease conditions.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) arises from the lining mucosa of the mouth and is by far the most frequent type, accounting for over 90% of all oral malignancies. Other types of malignancies that arise from different cell lineages are less frequent and include melanomas, sarcomas, malignant salivary gland tumours and odontogenic tumours, as well as malignancies of the jaws, those metastasising to jaws from distant organs and hematopoietic neoplasms such as lymphomas, leukaemias and multiple myeloma. Our focus here is primarily on oral squamous cell carcinomas that are of epithelial in origin, and as stated earlier that account for nearly 90% of all oral malignancies.

In Europe and North America over 50% of OSCCs are located on the lateral margins of the tongue and the floor of the mouth while in Sri Lanka and in neighbouring countries OSCCs are mostly found on the buccal mucosa, buccolabial commissure, sulci and around the retromolar trigone. However, OSCCs can also be found in any other locations of the oral cavity such as on the palate and gingiva.

Described below are the principal clinical characteristics of OSCCs and an appraisal on their differential diagnoses to facilitate early diagnosis.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma can be broadly divided in to initial or early stages and late or advanced stages of the disease based on the size and extent of the tumour at presentation. As cancers grow at different rates of proliferation what is usually referred to as early or late does not reflect on their times of evolution but simply the size at presentation, i.e. small or large in terms of the extent of the disease.

Early stages of oral squamous cell carcinoma

OSCCs initially manifest as localized and usually well-demarcated white/red (erythroleukoplakic) areas. Apart from their red or combined white-red colour, the only salient features of these lesions are their hardened texture and some surface granularity.

The early lesions of OSCC are usually non-ulcerated, though over time one or more ulcerated zones may appear on the erythroleukoplakic plaques, characterized by somewhat irregular margins, a gradual increase in depth, elevated margins and especially some loss of elasticity.

By the time the surface ulcerates (Fig. 1), evident hardening is noted in response to clinical exploration. This feature is referred to as “induration” and is pathognomonic to malignancy. The practitioner should, therefore, palpate any areas showing redness or ulceration and feel for any “induration”

Some months can elapse between the initial manifestation of the erythroleukoplakic plaques and appearance of ulceration. In the pre-ulcerative stages, the lesions are usually painless and may cause only some nonspecific discomfort. However, persistent pain irradiating to adjacent regions develops once the ulcerations appear. The pain gradually increases as the ulcerated surface increases.

The above-described characteristics, when a cancerous lesion measures less than 2 cm in maximum diameter, is considered to correspond to very early-stage OSCC. By the TNM classification (see below) this is considered a T1 lesion. Apart from the erythroleukoplakic area and ulceration, an initial lesion may also exhibit early exophytic tumour growth, with poorly defined margins. All of these clinical features ie erythema, ulceration and new growth may coexist in the early stages of OSCC. The presence of rolled margins and induration are the most significant features of malignancy.

The lesions become increasingly larger over time, and in a few months grow from less than 2 cm in size i.e., stage T1 beyond the limit of what is regarded as early-stage OSCC, to present in stage T2, a lesion measuring under 4 cm in size (Fig 1).

At this point, and with the described lesion dimensions, the patient presents with clear ulceration, accompanied by an expanding and exophytic tumour and especially with intense pain. The latter is now constant and radiates to more distant zones such as the external ear – especially in the case of tumours located on the tongue.

Differential diagnosis of the early stages of oral squamous cell carcinoma

As commented above, these early stages are characterized by erythroleukoplakic lesions, exophytic tumours or small ulcerations, and the differential diagnosis is established by considering the following disease conditions that may mimic a squamous cell carcinoma in its clinical appearance.

A. Traumatic lesions caused by mechanical factors such as ill-fitting dentures, chronic trauma from sharp/broken cusps of teeth or dental malpositioning,

B. Erythroplakia characterised by a red patch or erythroleukoplakia characterized by red or white-red plaques that cannot be removed by scraping.

C. Median rhomboid glossitis appearing as a red, bald patch on the dorsum of the tongue. This has a pathognomonic appearance with central depapilation and should not be confused with a carcinoma.

D. An eosinophilic ulcer which is an uncommon self-limiting chronic benign ulcerative lesion of the oral mucosa that it is similar to oral squamous cell carcinoma in its early stages.

E. Keratoacanthoma of the lip is a relatively common low-grade tumour originating in the pilosebaceous glands and closely resembling OSCC.

F. Necrotizing sialometaplasia is a rare condition that mimics OSCC, which is characterized by salivary gland metaplasia, necrosis and ulceration and often affects the palate.

G. Syphilitic chancre.

H. Benign growths which have a soft, smooth appearance of the overlying mucosa. eg. fibroepithelial polyp, epulis or granulomas

Some of these conditions may require biopsy verification to exclude malignancy (see later section)

Advanced stages of oral squamous cell carcinoma

Advanced stage OSCC is defined by the presence of a tumour measuring over 4 cm in size or infiltrating neighbouring structures. These stages of the disease manifest as extensive ulceration with significant in-depth infiltration or as exophytic growths sometimes with a verrucous component. It is common to observe combined clinical presentations characterized by ulceration and exophytic growth within the same tumour (Fig 2)

Advanced stage OSCC is associated with constant pain, with the need for frequent doses of analgesic medication. Narcotic agents are commonly required to control the pain, which radiates towards neighbouring structures such as the ear, or throat.

In addition to pain, advanced stage OSCC can be associated with mobility of teeth, bleeding and paraesthesia, Dental mobility usually manifests when the tumour infiltrates the periodontal tissues and the jaw bone. In the case of teeth not affected by periodontal disease secondary to dental plaque, spontaneous dental mobility manifesting in a short period of time should cause us to suspect underlying malignancy – particularly when the gum enveloping the tooth is swollen. If the dentist has removed such mobile teeth the socket may not heal as expected. A patient wearing a denture may complain of a lack of fitness of the denture.

A patient with an advanced malignancy will present with limitation of jaw movement, bad odour and fixation of the tongue. As the disease progresses a patient may present with facial asymmetry or an extraoral sinus tract with a fleshy outgrowth.

In the absence of antecedents of trauma (e.g., tooth extraction, dental surgery or injury), the presence of paraesthesia in an area such as the chin is always suggestive of a malignant lesion – whether clinically manifest or otherwise.

Neck metastasis

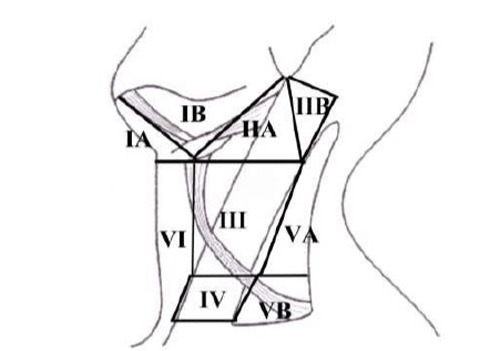

During the clinical examination, it is important to conduct a neck examination by palpation to assess the status of lymph nodes. The anatomy of the neck with reference to levels of lymph nodes is shown in Fig 3 to assist proper palpation.

OSCCs of the tongue, the floor of the mouth or mandibular gingiva have a strong tendency to produce neck metastases. The risk of regional lymph node metastasis in oral cancer is directly conditioned by the location of the primary tumour, its size (T stage), depth of invasion and, of course, some histological features such as lack of cohesiveness of tumour islands at the invasive front leading to vascular or lymphatic spread.

Cancers of the oral cavity usually drain to the upper lymph node levels I, II, and III, and to a lesser extent to lymph node level IV. Neck metastases can have a negative impact on prognosis.

Classification by TNM system

The TNM classification considers tumour size (T), the presence of affected regional lymph nodes (N), and the existence of distant metastatic spread (M) for staging the disease. Classifying a tumour by the TNM staging system allows the specialist in making treatment decisions and conveys prognostic information specific to cancer. Despite easy accessibility, most oral cancers are detected in T3 and T4 stages.

Adjunctive tests

A variety of optical devices and vital staining techniques are now commercially available to aid the clinician to inspect morphological changes that may be found in the oral cavity. These tools are referred to as diagnostic adjuncts or mistakenly as screening adjuncts. The most frequently reported adjunctive test to assess oral mucosal abnormalities is the toluidine blue (TB) test (Fig 4). Staining with Lugol’s iodine (Fig 5) is practised by maxillofacial surgeons. They have their place in secondary care facilities as these staining tools may assist in selecting the biopsy site, to determine the margins of cancer during surgery or in the surveillance of OPMDs during follow up. The optical devices (for example, VELscope, Vizilite, Microlux and Orascoptic) generally detect changes in the optical properties of the surface epithelium and submucosa based on light absorption, scattering, or fluorescence of tissue. Optical detection systems are based on the assumption that the structural and metabolic changes that take place in the mucosa during carcinogenesis give rise to distinct profiles of absorption and reflection when exposed to different types (wavelengths) of light or energy. Though these tools are highly sensitive to detect any abnormality their specificity is low and can result in false-positive detections, particularly when used as screening devices. They are generally not recommended for use in primary care facilities (4).

Referral

Once the dental practitioner notices any mucosal alteration suspicious of cancer (i.e. a red patch, a white and red patch with soreness, ulceration or a growth persisting for more than 2 weeks or a non-healing socket) it is paramount that the patient is urgently referred to a hospital consultant for further investigation. The criteria for early referral when suspecting oral cancer can be found in the NICE guidelines developed by the UK Department of Health (5). A patient arriving in a hospital with suspected cancer should be immediately investigated by a biopsy to rule out cancer and to confirm the diagnosis by a pathology examination.

Discussion

Unfortunately, OSCC often progresses undetected or is misdiagnosed by primary care practitioners. Almost half the patients experience diagnostic delays and over 50% present with advanced-stage disease. Cancers detected in the late stages are difficult to treat and morbidity and mortality associated with oral cancer are very high. Hence, early detection is key to a favourable prognosis. A high level of clinical suspicion and an awareness of the early symptoms is required among dental practitioners to enable its early detection.

References

1. Wong T, Wiesenfeld D. Oral Cancer. Aust Dent J. 2018 Mar;63 Suppl 1: S91-S99.

2. Warnakulasuriya S. Clinical features and presentation of oral potentially malignant disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018 Jun;125(6):582-590.

3. Fanaras N, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care. Prim Dent J. 2016 Feb 1;5(1):64-68.

4. Warnakulasuriya S. Diagnostic adjuncts on oral cancer and precancer: an update for practitioners. Br Dent J. 2017 Nov 10;223(9):663-666.

5. Head and neck cancers – recognition and referral. https://cks.nice.org.uk/head-and-neck-cancers-recognition-and-referral#!scenarioRecommendation:2

Figure Legends

Figure 1 – A malignant ulcer of the tongue with rolled margins in T2 stage

Figure 2 – An exophytic growth with a granular surface showing features of a squamous cell carcinoma

Figure 3 – Diagrammatic representation of lymph node levels in the neck

Figure 4 – A palatal ulcer stained with toluidine blue. A biopsy confirmed an early in-situ carcinoma.

Figure 5- Lugol’s iodine used to demarcate margins of a tongue carcinoma

Figure 1:A malignant ulcer of the tongue with rolled margins in T2 stage

Figure 2: An exophytic growth with a granular surface showing features of a squamous cell carcinoma

Figure 3: Diagrammatic representation of lymph node levels in the neck

Figure 4. A palatal ulcer stained with toluidine blue. A biopsy confirmed an early in-situ carcinoma

Figure 5. Lugol’s iodine used to demarcate margins of a tongue carcinoma.

No Comments