Places and people-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

From Panadura to Ratnapura the bus takes three hours to complete the ride. It goes through Horana, Ingiriya, Idangoda, Kiriella, and Kahangama before reaching its destination. The bus stop at Ratnapura is largely empty after six in the evening, and after eight there’s no one. It was raining last December. I was getting late. The clock struck 4.30 when I reached Kiriella. Another hour or so, and there wouldn’t be anyone to take me. I had come to visit Raddella, 25 minutes away. I would be staying for Christmas: I wanted an escape from the fireworks, and I wanted some peace and quiet. Raddella promised both.

Tucked away in a far off corner, Elapatha is one of 17 Divisional Secretariats in the Ratnapura District. The road to it is small, just wide enough for two vehicles to pass each other. Located seven kilometres from Ratnapura Town, it turns and swerves for three more kilometres before you reach a village called Karangoda. From there to Raddella it takes 10 minutes. Filled with forbidding roads and welcoming homes, Elapatha, to which it belongs, is located in Niwithigala, in turn a part of Palle Pattuwa in the Nawadun Korale.

The area is of immense historical interest, though it’s not obvious at first glance. Ratnapura, of course, features in the travels of Marco Polo. Yet this part of the country figured in the country’s history long, long before Polo’s visit, particularly in the reign of Parakramabahu I. In 1156 AD he faced a revolt in Ruhunurata led by the mother of an aspirant to the throne, Manabharana, whom he had defeated and vanquished. The mother, Sugala Devi, provoked an uprising in the South in the hopes of restoring the monarchy to her son.

The area is of immense historical interest, though it’s not obvious at first glance. Ratnapura, of course, features in the travels of Marco Polo. Yet this part of the country figured in the country’s history long, long before Polo’s visit, particularly in the reign of Parakramabahu I. In 1156 AD he faced a revolt in Ruhunurata led by the mother of an aspirant to the throne, Manabharana, whom he had defeated and vanquished. The mother, Sugala Devi, provoked an uprising in the South in the hopes of restoring the monarchy to her son.

Parakramabahu was by then engaged in bringing the country under one dominion, a feat unaccomplished since the days of Dutugemunu. Perturbed at the machinations of Sugala Devi, he ordered two of his generals, Damiladhikari Rakkha and Kacukinayaka Rakkha, to traverse to Ruhuna and subjugate her. The mission took years, and it threatened to drain the country’s resources. Yet in the end, the king triumphed.

Codrington speculated that Kacukinayaka Rakkha proceeded to Devanagama, or Dondra, after suffering defeat at Mahavalukagama, or Weligama. From there he and his army made their way through Kammaragama (Kamburugama), Mahapanalagama, Manakapithi, the ford of the Nilwala River, and Kadalipathi. Damiladhikari Rakkha, on the other hand, had taken the route from Ratnapura: Codrington wrote that he may have gone through the mountains between Rakwana and Deniyaya, or the mountains of the Kolonne Korale on the outskirts of the Ratnapura District. Either way, he reached Koggala, and from there to Magama, where he waged a series of battles after which, finally, he won the war.

As they marched through Ratnapura, Damiladhikari’s troops captured the villages of Donivagga (Denawaka) and Navayojana (Nawadun). From there we are told they advanced to Kalagiribanda, or Kalugalbodarata, encompassing the Kukul, Atakalan, Kolonna, and Morawaka Korales; from there, to the Atakalan Korale, Dandava between Kahawatte and Opanayake, Tambagamuwa near Madampe, Bogahawela, Binnegama, and finally Butkanda. Nawadun, roughly the Nawadun Korale of today, hence became the army’s first priority; so impossible to claim did it become that the army despaired of it as “hard to pass through.” During the civil war Parakramabahu had waged with Manabharana, he set about taking the region from Manabharana’s forces, and eventually succeeded in doing so.

The writing of the Tripitakaya precedes Parakramabahu, Manabharana, and Sugala Devi by several centuries. It was in Nawadun that the first puskola poth on which it would be written were made. Two kilometres before Raddella, you stop by the village of Karangoda, which reputedly got its name from the word given to the remnants of ola leaves after they’ve been used to make books. Here, at a temple less well heard of than anything Parakramabahu built and came up with, the first talipot books were put together for the Fourth Buddhist Council. Thus the region from Elapatha to Raddella is linked to two of the most important events in our history: the unification of the Sangha by Vatta Gamini Abhaya, and the unification of the polity by Parakramabahu I a thousand years later.

After Vatta Gamini Abhaya suffered defeat at the hands of a South Indian dynasty, he and a group of his most faithful followers retreated from the capital, Anuradhapura. Among them was a monk, Kushikkala Tissa; he would settle in Karangoda with his disciples and several other refugees from the war torn capital. The village of Weragama is not too far away, and there a sentry by the name of Bodhinayake, who befitting his title had been in charge of the Sri Maha Bodhiya, founded a settlement of his own, giving it its present-day name. Those who hail from the Bodhinayake line, according to local sources, continue to reside in the area. Its history, and the history of the sangha parapura from Kushikkala Tissa, has a great deal to do with that temple in Karangoda: the Potgul Viharaya.

Locals call Potgula the second Sri Pada. There’s no real resemblance: the association with the latter comes off mainly in the fact that locals, and even those passing by the area, tend to pay their respects to it before making their way to the Holy Peak. Not unlike the maha giri dambe at Sri Pada there’s a series of steps – 460 according to a pamphlet issued at the temple, 469 according to Explore Sri Lanka – to ascend before reaching the viharaya. The climb stiffens the limbs, though shorter than Dambulla. Yet despite its reputation, not many seem to have heard of it: an anomaly that proves to be more curious when you consider its history is tied, inextricably, to the history of the Buddhist order in Sri Lanka.

A. H. Mirando has written of the emergence of Ganinnanses or lay monks, comparable to the Achars of Cambodia, in Kandy in the 17th and 18th centuries. With vast sections of land coming into their possession, he observes, they remained priests in name only, contravening the rules of Vinaya and getting involved in the affairs of the laity. Owing to their persecution by the tempestuous Sitawaka Rajasinghe, many Buddhist monks fled to Kotte, contributing to the disintegration of the Sangha in the upcountry further. Dutch and British annexation of the littoral regions distanced the Kandyan priesthood from low country monks, compelling the latter to seek favours from colonial officials.

The descendants of Kushikkala Tissa had made Potgula their sanctuary, and despite the moral decline of the Ganinnanses, the sangha parapura flourished. We next hear of a Chief Incumbent whose contribution to the revival of Buddhism has been as scantily noticed as the historical significance of the Potgul Viharaya itself: Vehalle Sri Dhamadinna. Together with Sitinamaluwe Dhammajoti, the last non-Govigama monk to be initiated into the Siyam Nikaya, Dhamadinna began a campaign to breathe new life to the order and the doctrine in the Maritime Provinces. The two of them had been ordained by Kadurupokune Navaratne Buddharakkitha, who resided in Tissamaharama and became one of two monks initiating a generation of reformists to the priesthood; the other, Suriyagoda Kitsirigoda, Rajaguru and Dhammanusasaka of Narendrasinghe, would ordain Velivita Saranankara.

In 1753 when the upasampadawa was finally established under Kirti Sri Rajasinghe and Buddharakkitha’s students underwent the ceremony to symbolise the beginning of the new chapter, Dhammadinna, who took part in it with 22 Ganinnanses from Sabaragamuwa and 20 Ganinnanses from Matara, would have been 74; if so he was 97 when he passed away in 1776. Together with Malimbada Dhammadara and Kumburupitiye Gunaratne, he formed a trio of low country monks who, after Saranankara’s demise, were placed in charge of the Shrine at the Sri Pada. This proved to be a source of contention once they came to hold two offices – Chief Monk of the low country and the Shrine – following the separation of those offices after Kamburupitiye Gunaratne’s passing away in 1779.

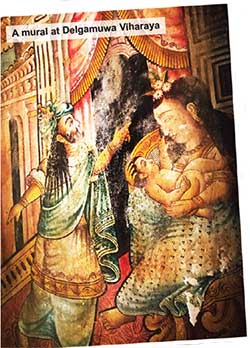

Far, far away, 12 kilometres from Raddella, the Sumana Saman Devalaya continues to occupy a preeminent place in the Sabaragamuwa Province. 13 kilometres away in Kuruwita, the Delgamuwa Viharaya, a quiet, empty, yet still hallowed reflection of its past, links the entire region to the patronage of Buddhism. It was to Delgamuwa that Mayadunne moved the Tooth Relic in the early 16th century. Faced with the threat of destruction at the hands of Portuguese marauders and proselytisers in Kotte, it remained hidden beneath a kurahan gala in Delgamuwa for 43 years. Around it an entire culture and way of life came into being: Sabaragamuwa natum, instituted for the perahera of the Relic, and angampora, instituted for the protection of the Relic from thieves, spies, and proselytisers.

Tourists and devotees flock by the hundreds to the Saman Devalaya, yet few, if any, seem to visit Delgamuwa. The road to it is narrow, empty, and quiet: house after house line up along the way, reminding you more of a suburb than a religious site.

Potgula endures the same fate, though more pilgrims make their way there. There, at the viharaya after climbing the 40 or so steps, you come across a well full of holy water – and plastic cups to drink it with, used and reused by devotees and visitors – as well as a stupa, a watering hole, a swarm of wasps said to be descendants of the sentries who had guarded the temple, and a long, winding, though enclosed tunnel which some believe goes up to the Ehelepola Walawwa in Ratnapura town. Regarding the latter, no one really knows where it ends: a local told me someone tried to test the Ehelepola Walawwa thesis and lost his way, never to be found again. Vatta Gamini Abhaya apparently hid himself here, though locals dispute it: according to them, given his contribution to Buddhism, temples everywhere went on claiming that he and his family sought shelter in them.

Living next to these edifices, genuflecting to them, but also dispelling them of the myths surrounding them, are the people of Ratnapura. At least one local I met took me by surprise with his candour. Unlike the people of the South who tend to accept unconditionally the folklore their societies are rooted in, their counterparts here who I met didn’t seem to buy the Orientalist aura visitors conjure up about their surroundings.

Modernity in the Western, cosmetic sense has obviously arrived, and you see it in patches everywhere. The old cohabits with the new. Thus family bonds are reinforced and adhered to, while the lucrative occupations – not just gem mining but also textiles, groceries, and the law – are breaking them apart. Religiosity exists with rationalism: one generation follows the myths of popular Buddhism, while the other spurns them. And of course, there’s the dialect. Osmund Jayaratne, canvassing for the LSSP here, was once offered a maluwa. Expecting fish, he was astonished at being handed a completely vegetarian lunch: “Maluwa,” he was told, “can include anything with rice in it.” Things have in one sense changed from then – a period of half a century – yet in another, they have not: I too could barely conceal my astonishment when, expecting fish, I was handed a maluwa full of anything but fish.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com