Polonnaruwa: Rise and fall-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

The chronicles mention Polonnaruwa (Pulaththinagara in Pali) long before its advent as the capital of the country. We come across it in the Culavamsa in connection with the reigns of Aggabodhi IV and Aggabodhi VII, both of whom were residing there at the time of their passing away. A general by the name of Sena, who rebelled against the king of his time, is said to have made it his own capital before facing defeat at the hands of that king, Sena V. By no means infrequent, such encounters bolstered the city’s growing importance. Moreover, at the peak of the Anuradhapura period particularist tendencies had begun to spring up in the south in Rohana. Situated between Rohana and Rajarata, Polonnaruwa offered the ideal outpost from which such tendencies could be put down.

Far more important and pertinent, however, were the shifts of dynastic politics in South India and the concurrent strengthening of the hands of Dravidian mercenaries in Sri Lanka. The infighting between the Pandyans, Colas, and Pallavas on the one hand and the diminution of strength among the Calukyis in the Deccan shifted the locus of South Indian politics from the mainland to the coastline. Indeed, the weakening of the Pallava dynasty in Kanchi and the revival of the Pandya kingdom in Madurai led the Pandyan Srivallabha to invade Sri Lanka, where, supported by local fifth columns, his army, “like the hosts of Mara”, ransacked Anuradhapura “as if it had been plundered by yakkhas.”

Somewhere in the ninth century AD, around 850 AD to be specific, Vijayalala, a general serving the Pallavas who claimed descent from the Colas, moved into and occupied Tanjore; his son, Aditya I, fought and prevailed over the Pandyans 30 years later. More expansionist than its predecessors, the new Cola dynasty sought to conquer Sri Lanka with much more vigour and ruthlessness.

Mahinda IV, perhaps one of the more pragmatist kings the country had, immediately entered into an alliance with the Kalingas of Orissa (or Malaysia, according to Senerat Paranavitana, though this line of reasoning has since been discounted). The decision to enter into such an alliance was based on two considerations: the weakening of the Calukyas, who could otherwise have been counted on as enemy-of-enemy-friend against the Colas, and the historical link between Sri Lanka and Kalinga, going as far back as the Vijayan dynasty. Yet such marriages of convenience – literally, since these new alliances were based on matrimony – could not survive the expansionist aims of the Colas, and thus conditions that had been peaceable, if not negotiable, under Mahinda IV deteriorated under Sena V and Mahinda V. As is usually the case, the blame has to go to the latter two kings for their inefficient and immature statecraft; the Culavamsa describes Mahinda V in particular as being “of very weak character.”

As Anuradhapura disintegrated under these fatal contradictions, the Colas gained in strength; under Rajaraja I and his son Rajendra I, Cola foreign policy became more expansionist than ever before. To the West they held firmly against the Calukyas, but to maintain a balance between the mainland and the coastline, it was felt necessary to encircle the Bay of Bengal.

As Anuradhapura disintegrated under these fatal contradictions, the Colas gained in strength; under Rajaraja I and his son Rajendra I, Cola foreign policy became more expansionist than ever before. To the West they held firmly against the Calukyas, but to maintain a balance between the mainland and the coastline, it was felt necessary to encircle the Bay of Bengal.

Sri Lanka hence figured in the Cola scheme of things more significantly than it had done until then, and so, in the first five years of the 11th century, Rajaraja invaded and occupied the northern part of the country. In 1017, Rajendra I expanded into Rohana and captured Mahinda V. The latter became the first Sinhala king to be captured by a foreign force; he would be followed four centuries later by Vira Alakeshwara, this time by a Chinese general. To the reader of Sri Lankan history who sees these incidents as differing only slightly from our tug-of-war vis-à-vis India and China today, it can only be said that such analogies, while unhistorical, are not entirely unjustified.

From their outpost in the north of the country, the Cola administrators turned Polonnaruwa, which they renamed Jananathapura, into a treasury for their shrines and devales. From Polonnaruwa they attempted to control Ruhuna, but ironically, the particularist tendencies that the Anuradhapura kings had tried to quash rose up against the Colas; the latter tried, for instance, to capture Mahinda VI’s son Kassapa (or Vikramabahu), but neither could they defeat him nor could he them. Kassapa’s death was followed by a crisis: no fewer than five chiefs ruled at Rohana, and yet none of them could overcome infighting between themselves to pose a formidable enough threat to the north.

While Rajadhiraja I attempted and failed to bring Rohana under his control, events closer to home threatened to reduce his power and jurisdiction. The Calukyas, who had been beaten off the track by Rajaraja, were back in the game, scaling up the odds against the Colas. Having fallen in battle against the resurgent Calukyas, Rajadhiraja was succeeded by his brother Rajendra II, who held the line, but only barely. Against the backdrop of diminishing military fortunes and depleting treasuries, the Colas quickly switched from encircling the coastline to defending the mainland. Yet their attempts at getting Ruhuna to accept their suzerainty did not let go, with Rajendra II despatching a successful expedition in 1053 or 1054, which in all fairness confirmed the strength of Cola vassals to the north more than it did the diminution of influence among the rulers of Ruhuna.

In any case, whatever hopes the Colas had of a victory in the Deccan and Ruhuna faded away upon the death of their king and his successor, Virarajendra. The latter’s accession to the Cola throne was followed by a dynastic dispute that favoured the new Calukya king, Vikramaditya VI. More ambitious than his predecessors, Vikramaditya VI consolidated power long enough to ward off the possibility of Cola recovery or resurgence; that fed into the rebelliousness of the Pandyans and the Ruhuna rulers. It was against this setting that Vijayabahu, having mounted one campaign after another, claimed victory and was consecrated king in 1073: the first to unify a Sinhala polity in disarray.

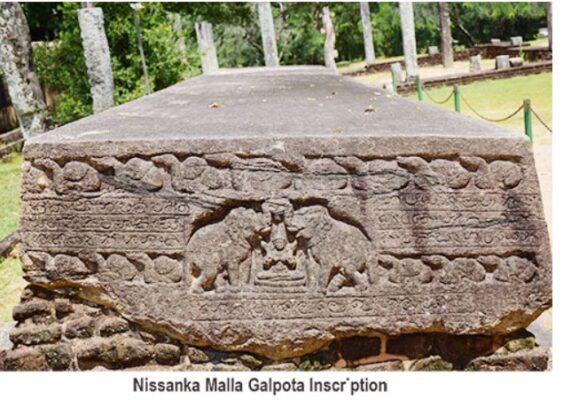

Under the trio of kings generally associated with the rise and growth of Polonnaruwa – Vijayabahu, Parakramabahu I, and Nissanka Malla – the state expanded and regained some of the stamina it had lost to the onslaughts of Cola invasion. Yet it would be incorrect, as popular myth holds it, to say that these kings did away completely with Dravidian influence. Vijayabahu, for instance, found it difficult to rule without cooperating with the Velakkaras, a group of mercenaries who had earlier pledged their loyalty to the Colas but now retreated from them; so much of an influence did they gain in the Sinhala court that, during the reign of one of Parakramabahu’s successors, Vikramabahu II, they were able to gain control of the Tooth Relic. Indeed, the allowance made by these Sinhala kings to the Velakkaras indicates that to hold on to power, rulers had to concede some of it to mercenaries.

By itself, this does not, and cannot, explain the disintegration of the Polonnaruwa polity following the death of Nissanka Malla. For an explanation of why the kingdom crumbled down as it did, we should couple it with another crucial factor: the persistence with which Parakramabahu and to a lesser extent Nissanka Malla sought to eliminate particularist tendencies, especially in the south. Parakramabahu, of course, had come to power after waging a series of campaigns against regional polities: he would mount such campaigns even after assuming the crown. This had the effect of quashing any tendency towards regionalism that the state could have mobilised against Kalinga Magha’s intervention in the 13th century. Deprived of a convenient ally, the entire polity instead fell apart.

To these two factors – the presence of Dravidian troops and the repression of particularism – we must add two more: the rate at which the state, in particular under Parakramabahu I, was allowed to expand, plus the carte blanche given to the diversion of state resources to massive works of irrigation and – in the case of Nissanka Malla as well – ambitious, yet costly foreign expeditions.

To these two factors – the presence of Dravidian troops and the repression of particularism – we must add two more: the rate at which the state, in particular under Parakramabahu I, was allowed to expand, plus the carte blanche given to the diversion of state resources to massive works of irrigation and – in the case of Nissanka Malla as well – ambitious, yet costly foreign expeditions.

Regarding the second point, James Handawela, a veteran irrigation officer, has in a book which has unfortunately not got the attention it deserves come up with a novel contention: that far from fostering self-sufficiency in agriculture, Parakramabahu, by investing heavily on massive irrigation works while dragooning labour from farmers engaged in watershed farming, pre-empted the setting up of a viable self-sufficient network. This thesis is controversial, and it has not, to the best of my knowledge, been assessed by any other scholar; it deserves debate and, in the least, re-examination.

To me it raises an important question: to what extent were we self-sufficient? Popular historiography has it that under Parakramabahu I, Polonnaruwa flourished as some sort of a granary of the East. Yet that does not mean the state cut itself off from trade and engagement with the rest of the region: as the anthropologist Eric Wolf has argued, civilisations rooted in a tributary mode of production – which is what Sinhala civilisation was – operated weakly or strongly in relation to other polities. Peaceable as civilisations spread around the Indian Ocean may doubtless have been, then, maritime commerce did to a certain extent shore up antagonisms between these polities. Hence when Parakramabahu I forged closer ties with the Khmer kingdom in Cambodia, Alaungsithu of Burma, which had maintained close politico-religious relations with Sri Lanka, obstructed the latter’s elephant trade with South-East Asia, compelling the king of Polonnaruwa to embark on an expedition to Lower Burma.

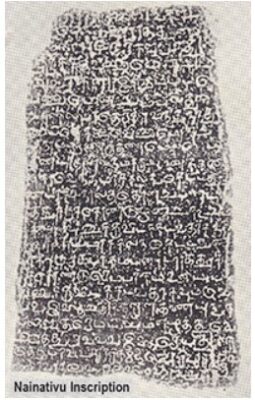

As symbolic of the growing importance attached to trade during this period was the emergence of a mercantile community in Sri Lanka. Perhaps the best epigraphic evidence we have for how trade went ahead in Parakramabahu’s reign is the Nainativu Tamil Inscription; one of the oldest such inscriptions in that language unearthed in Jaffna, it offers us glimpses of not just the customs regulations enforced back then, but also the protection meted out to foreigners plus some of the more interesting items we were importing at the time, like (of all merchandise) elephants.

Eric Wolf has shown us how tributary rulers maintained a contradictory attitude to merchants: they allowed the latter to mingle with their societies, but not to the extent of overturning established belief systems and political hierarchies. So it was with Polonnaruwa. Not until several centuries later, after the downfall of the last Sinhala kingdom, would the economy be integrated into, and disfigured by, a system run on plantation and mercantile wealth: capitalist to some, pre-capitalist to me.

Yet as the history of Polonnaruwa vividly shows, we were never completely cut off from the vagaries of trade; it’s just that we remained somewhat unfamiliar with newer systems of exchange developing further to the West. Vinod Moonesinghe puts it better than most in his explanation of the difference between these systems and ours: as much during Polonnaruwa as during Anuradhapura, he contends, “trade was conducted for the benefit of all.” Whether under Parakramabahu or under the kings of the southwest, trade thus remained, if not the cornerstone, then at the centre, of engagement with the rest of the world: hardly the isolationist granary of the East romanticised by many today.