Race, class, and Wigneswaran’s historiography – By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

Former Chief Minister Wigneswaran made two remarks at the commencement of the 16th parliament. First he contended that Tamil is the oldest surviving language, presumably in the world. Then he contended that the Tamil people are this country’s original inhabitants. Since I do not know much Tamil, I am not sure whether something got lost in the translation provided by the TV channels and news outlets which broadcast the parliamentary session. In any case, this essay should not be construed as a refutation or an endorsement of what the former Chief Minister of the Northern Province, now an MP from a splinter group of what was not too long ago the dominant political party in that region, said.

Regarding MP Wigneswaran’s first assertion, all I can say is there’s much evidence for his view. He is certainly not the first South Asian politician to make such a claim, nor will he be the last. In September last year at the UN General Assembly, for instance, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi called Tamil “the most ancient language in the world.”

Spoken by more than 70 million people, including the present CEO of Google, Tamil has gone on record as the first language with its own grammar guide: Tolkāppiyam, reputedly published in 2500 BC. As one scholar remarked, “who can publish a book on grammar when other languages were in trouble [just] to shape out their alphabets?”

Archaeological evidence points at a considerably old, rich history, with different estimates for the age of the language. On the border between Madurai and Sivangangai in Tamil Nadu, for instance, is the village of Keezhadi, where excavations made around seven years ago have been dated by historians at between the fifth century BC and third century AD. The remains of earthen urns in Adichanallur and Kodumudi, on the other hand, tell us of a history that goes back 2,000 to 2,500 years. A stone inscription in Thanjavur, more than 160 kilometres from Kodumadi, hints at a linguistic history spanning 10,000 years. There is much debate about which came first, Tamil or Sanskrit, but the popular view is that since it used Sanskrit rather sparingly in its early days, Tamil came first.

Does this validate or vindicate ex-Chief Minister Wigneswaran’s second assertion? It really depends on how you look at it. I assume, given the emphasis he puts on it, that when he talks about Tamils being the original inhabitants of the country, the ex-Chief Minister and now MP is seeing them in racial terms. Thus a long history of 2,500 years, if we are to take the Adichanallur-Kodumadi remains as our foundation, is reduced to a single community, a single race, bearing the same characteristics then as now, and presumably harbouring the same aspirations. This is something even those on the other side, i.e. the Sinhala Buddhist nationalist crowd, do: assume that a racial community, as it stands today, stood in the same light from its inception. That is how films and novels projecting Sinhala or Tamil nationalist narratives pit one race against the other, as though every historical battle involving these communities was exactly that: one race versus another.

When we make such assumptions, we automatically graft modern day labels and epithets on a past that is as elusive as it is ineffable. This view of the past, paraphrasing R. A. L. H. Gunawardana in his groundbreaking essay “The People of the Lion”, happens to be moulded by contemporary ideology, so much so that popular works of art based on what happened 2,000 years ago use such terms as “demala” and “sinhalaya” broadly, crassly, and carelessly, without accounting for the specific historical context in which they were uttered, written down, and recorded, even by monks and priests.

The writings of those who critique Sinhala nationalism can just as well be used to critique Tamil nationalism. H. L. Seneviratne in a lecture delivered at the International Centre for Ethnic Studies in 2002 (titled “Buddhism, Identity, and Conflict”) observed that contrary to the conventional wisdom, the Dutugemunu-Elara conflict was “more complicated than is generally understood in the nationalist reading of the Mahavamsa.” He cited Gunawardana for this view, having noted earlier that in ancient Sri Lanka, “there were Sinhalas who were not Buddhists and Buddhists who were not Sinhalas.” It is only fair to apply this to the Tamil community as well: after all, Dutugemunu’s army had soldiers of Tamil extraction, just as Elara’s army had those of Sinhala extraction. Unfortunately, for some reason or the other, while many Sinhala scholars are willing to take up the cudgels against nationalists spouting historical myths, not many Tamil scholars seem to do so.

It would be better to accept the available historical evidence and go on believing that the evolution and growth of identity and group consciousness in Sri Lanka was less moulded by race and religion than what scholars from both sides of the divide suggest. In the service of historians, nationalism turns out to be a petty bourgeois ideology, representing the interests of a stunted middle class searching for more room in a diminishing economic space. It is this ideology that goes into the production of big budget historical epics, and it is this ideology that both Tamil and Sinhala nationalists alike propound.

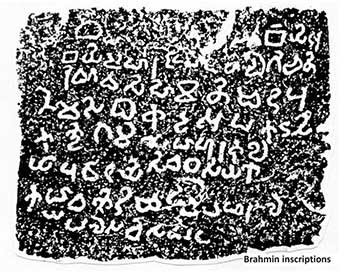

To put it briefly, identities never evolved as races; they evolved as lineages, which in turn were rooted in occupations and professions rather than ethnicity. For instance, the Brahmi inscriptions, of which there are many in Sri Lanka and India, emphasise a donor’s station in life: Kaboja, Milaka, Dameda, Barata, and so on. Moreover we have Yaksha, Naga, Vedic, and Puranic inscriptions, and they all allude to the status of their authors, their families, and their occupations. The Puranic inscriptions in particular tell us of pre-Buddhist religious cults that revolved around Vishnu and Siva, which lends credence to G. P. Malalasekara’s view that as a monarch, Vijaya was tolerant of all faiths.

Significantly, not a few of the inscriptions include the terms “upasika” and “upasaka”, denoting what could be the beginnings of a religious identity. But this is at best peripheral. I have written on these inscriptions in an essay elsewhere, where I attempted to trace the contours of Sinhala nationalism in the 20th century to the Hela Havula’s historiography, as seen for instance in their view that Kuveni’s act of spinning a wheel at the time of her first encounter with Vijaya showed that, prior to the Indo-Aryan colonisation, there had been a flourishing, advanced civilisation here.

It is dangerous to rely on such literal interpretations of historical texts. Even more dangerous is to deconstruct the narrative in such texts in terms of contemporary notions of ethnicity. Mervyn de Silva, in one of his last essays, prophetically noted that “in this age of identity, ethnicity walks on water.” This has always been the case. To contend otherwise would be to read into the meanings of words and epithets, and to claim, as ex-Chief Minister Wigneswaran does, that this country was inhabited originally by one race or community. What results from such a crass reading of these texts are thus not historical documents, but alternative histories and worse, exclusivist narratives.

That, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. Racism and racialism are not products of Western civilisation and they are not its preserve either. But race as is understood today was certainly the product of two Western trends: imperialism and orientalism. The term itself dates, in Europe, from the 16th century onwards: the era of Hobbes, Locke, and later, Montesquieu, the likes of whom actively sought to prove that democracy, the rights of the individual, and sovereignty did not apply to dark-skinned and “inferior” people. The work of William Jones, who tried to show the link between Sanskrit and European languages, must be cited here, as must that of Max Müller, who claimed superiority for Indo-Aryan culture and provided the ideological rung for the Nazi ladder.

The end result of it all was, as Vinod Moonesinghe correctly noted many years ago in this paper, that the British, subsequent to their occupation of this country, played up the divide-and-rule game by trying to prove that the Sinhalese (“Aryans”) belonged to a superior race and Tamils (Dravidians) were of a lesser order: a tactic which boomeranged spectacularly when Sinhala elites used this logic against the British themselves.

I mentioned this as the tip of the iceberg. Why? Because when we talk about race so crudely and simplistically, we not only forget that they meant completely different things to people from centuries ago, we also lay aside the fact that any talk of race must necessarily be at the expense of class, undoubtedly most pervasive social division today.

Thus those opposed to Sinhala nationalism claim that there has always been systematic discrimination by Sinhala people, of all backgrounds, against the Tamil community, failing to distinguish between the lower and the higher ends of the social hierarchy. When it is made clear that under British rule the two most discriminated communities were Indian plantation workers (Tamil) and Kandyan peasants (Sinhala), academics argue that the Kandyan peasant was not as marginalised as the evidence points out, simply by virtue of the fact that he had elite backing. Thus Mick Moore writes of a “Sinhalese myth of the plantation impact”, while Vijaya Samaraweera writes of “nationalist political leaders.” What is forgotten here is that class can often, if not more often than not, override ethnicity.

One of the many things I agree with Marx is his view that agrarian communities can be collectively considered as a class in itself (rather than a class for itself, since it did not in the beginning have representation). This is certainly applicable to the Sinhala peasant, which often makes me wonder why it is that we don’t read Marx more.

The truth was that class, and caste, determined the fortunes of political representatives and elites from that era. The class limitations of the colonial bourgeoisie, despite their supposed liberalism and support for the peasantry, can be seen in the fact that they vetoed proposals for universal franchise and, later, free education: proposals which, if implemented in full, would have had their biggest impact on the peasantry.

Their nationalism, as with their reformism, was limited by their economic interests. “They were men acting in the interests of their classes,” wrote N. Shanmugaratnam: “the native landed proprietors, the native owners of graphite mines, and the comprador bourgeoisie.” There was nothing to suggest, as Moore does, that the conflict was solely between colonial officials and capitalist elites. “The interests of the Ceylonese planters,” observed James Peiris in 1908, “are identical with those of the European planters.” In such a situation, it is difficult to imagine that Sinhala peasants were behind Sinhala elites, and not behind the more cosmopolitan Left, which, after all, agitated for reforms that benefitted them: not just the franchise and free education, but also the Paddy Lands Act.

So the Sinhala peasantry, along with the Tamil peasantry, ought to be considered apart from the Sinhala bourgeoisie. Where Sinhala and Tamil nationalists, who are overwhelmingly petty bourgeois and thus allied, with or without their knowledge, with a class that has a definite stake in dividing communities to maintain its hold, have gone wrong is their belief that all these communities and formations can be considered as one. Sinhala peasants are accordingly put into the same basket as Sinhala elites: a classic error.

In a later essay I will elaborate on the pitfalls of that kind of reasoning, but for the moment all I can point at as evidence for how political history rebels against this reasoning is the fact that, in the 1982 presidential election, the Jaffna people gave their preference to the SLFP candidate over the UNP candidate, beating J. R. Jayewardene to third place. The reason was simple economics: the Jaffna farmer had benefited under Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s agrarian policies. Had the Jaffna farmer considered himself a descendant of the original inhabitants of the country, he would not have given his vote to a “Sinhala Buddhist” party so openly. Now the thing with history is that it has a habit of repeating itself, as the ex-Chief Minister and MP ought to be aware: in the recent general election, the Jaffna people again gave a sizeable chunk of their votes to the SLFP, over the SJB.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

No Comments