Rediscovering Sri Lanka through a travel memoir

Source:Asia.Nikkei

Colombo’s Mount Lavinia Hotel in the 1960s. One of Asia’s legendary colonial hotels, it was managed by the author’s father through the political upheaval of the 1970s. “It was a turbulent time, much of which my father spent in remand and jail.” (Photo courtesy of Razeen Sally)

Foreign visitors have for centuries rhapsodized about Sri Lanka, or Ceylon as it was called until 1972: its seashores and landscapes, its governing religion, Buddhism, and its majority ethnicity, the Sinhalese.

Hermann Hesse, visiting in 1911, called it “Paradise island with its fern trees and palm-lined shores and gentle doe-eyed Sinhalese.” Two decades later, George Bernard Shaw thought Ceylon “India without the hassle.” Well over a millennium earlier, Arab traders called the island Serendib, the origin of “serendipity,” which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way.”

What foreign visitors cannot fathom is how this land of serendipity could tear itself apart for a quarter-century in a Sinhalese-Tamil civil war that lasted until 2009. Nor can they make sense of two Marxist-influenced rebellions in the Sinhalese south in the early 1970s and late 1980s, both viciously prosecuted and brutally crushed.

This is Sri Lanka’s glaring paradox: its mix of beguiling tourist charm and an astonishing record of violence. It puzzled me as a child growing up in Sri Lanka, and during my long adult absence. It was the burning question that set me off on my rediscovery of Sri Lanka in my late forties and early fifties.

I am “half-half,” the firstborn of an Anglo-Welsh mother and Sri Lankan-Muslim father. They met on a ship in 1955; my mother came to Ceylon to get married in 1961. My childhood was set in 1970s’ Colombo and its suburb of Mount Lavinia, where my father ran the Mount Lavinia Hotel, one of Asia’s legendary colonial hotels. It was a turbulent time, much of which my father spent in remand and jail. We left in the late 1970s, after which Sri Lanka receded from my mind.

Top: The author’s parents’ wedding photo. After meeting on a ship in 1955, the author’s Welsh “mother came to Ceylon to get married in June, 1961. Bottom: The Razeena estate bungalow, Uva, December 2014. “I spent my school holidays at ‘Razeena,’ a little tea estate my uncle had bought, about an hour’s drive from Badulla. (Photos courtesy of Razeen Sally)

On my first trip back, a few years after my father died, I realized a book project would be the most thorough way of getting reacquainted with Sri Lanka. I knew I did not want to write the kind of academic or policy book I had written before. I wanted to write about Sri Lanka differently, as a writer, not as a professor or policy wonk.

What emerged was a travel memoir. The “memoir” is my personal story: childhood, absence, and return. The “travel” is the journeys I did, mostly long road trips crisscrossing the island. Classic travel books use the medium of the journey to capture something bigger and transcendent, a spirit of time and place. So I used my memoir and journeys to address the big, broad themes of Sri Lanka’s history, culture, religions, and current affairs, and to capture, as best I could, the spirit of Sri Lanka in the decade after the end of its civil war.

My point of departure was a yearning for childhood reconnection. I saw Ceylon in the 1960s through my mother’s eyes: her arrival in Colombo harbor, wedding, and conversion to Islam in June 1961; her immersion in a Muslim extended family and my father’s wide circle of Sinhala-Buddhist, Tamil-Hindu and Burgher-Christian friends. These were happy early married years, set in a verdant, spacious and airy Colombo, with the occasional outstation trip on narrow, bumpy roads to colonial rest houses in otherwise undisturbed rural idylls — before the age of mass tourism and air-conditioned hotels.

My childhood memories, mostly of 1970s’ Colombo, are bittersweet: bitter with the taste of crises surrounding my father’s court case and subsequent incarceration; with down-at-heel Colombo, ravaged by strikes, rationing and bread queues; and with Mrs. Bandaranaike’s government, which turned politics authoritarian, degraded public institutions, ruined the economy, and fanned communal flames.

But sweet moments lightened my existence. Mount Lavinia Hotel gave me a lifelong fondness for colonial hotels in the tropics. I was in and out of my cousins’ houses every day, playing cricket, cards, and table tennis. There were Sunday sea baths with my father and male cousins, framed by a cerulean sky and the Indian Ocean lapping the city shoreline.

Top: Uva hills in the mist, December 2015. Uva is one of Sri Lanka’s main tea-growing provinces. Bottom: The author, Razeen Sally, right, and his driver Joseph, on a road trip in 2015. “My road trips out of Colombo covered tens of thousands of miles.” (Photos courtesy of Razeen Sally)

We left for the UK in 1977. I went back infrequently over the next three decades. In those years the country changed, mostly for the worse. The murder of thirteen soldiers, and retaliatory riots against Tamils in Colombo, both in “Black July” 1983, started a civil war that ended with the Sri Lankan army’s total, blood-drenched victory over the Tamil Tigers in May 2009. Colombo grew tattier. Army checkpoints and barbed wire popped up everywhere. Bombs went off. But the city also expanded and densified with condos, shopping malls, five-star hotels, congestion, and suburban sprawl.

This was the hometown I rediscovered just before the war ended. But after the war, Colombo was “beautified.” Security checkpoints and barbed wire disappeared and life returned to peacetime normality. Streets were cleaned, roads carpeted, public buildings freshly painted, slums cleared and megaprojects drawn up. A Chinese-built Port City rises on 270 hectares of reclaimed land from the sea. Luxury condos, malls, and hotels of shimmering glass tower over what was a very low skyline. On lakefront land, a “Lotus Tower” — also Chinese-built — dwarfs everything else in the city like Gulliver in Lilliput.

Home Town is not what it used to be. There is less inter-ethnic mixing. People are more opportunistic and sharp-elbowed, grabbing what they can, imitating the greed of the elites. Still, for all its expansion since the late 1970s, Colombo retains a small-town vibe. It looks and feels spacious compared with other developing nation cities. People still promenade languidly on Galle Face Green during an Indian Ocean sunset. Timekeeping is as casual as it always was: punctuality passes by default. The city is still a multi-ethnic, religious and linguistic hotchpotch; what vigor it has would be much diminished without it. But this mix can also be a tinderbox when Hermann Hesse’s “gentle doe-eyed Sinhalese” turn into a feral mob. Or when Islamist suicide bombers blow up churches and hotels.

My road trips out of Colombo covered tens of thousands of miles. I drove around nearly all Sri Lanka’s coastline — in the south and deep south, past the deserted powder-white beaches and waveless, crystal-clear waters of the east coast, around the marshy, palmyra-clad islands off the Jaffna peninsula, to Talaimannar pier at the tip of Mannar island and the Kalpitiya peninsula on the west coast.

I retraced the paths of Buddhist sages, Sinhala kings, and Tamil invaders among the ruined temples, palaces, and statues of Rajarata, the “Land of Kings” in the north-central part of the island, and walked all over the tea-carpeted hills of Kandy, Nuwara Eliya, Bogowantalawa and Uva. In a sea of pilgrims, I climbed Adam’s Peak, Sri Lanka’s holiest mountain, to see the sunrise. In Colombo and on the road, I had hundreds of encounters and conversations. For nearly four years, from 2015 to late 2018, I had a ringside seat as a policy adviser to the prime minister and minister of finance, watching Sri Lanka’s disastrous politicians miss another opportunity for national renewal.

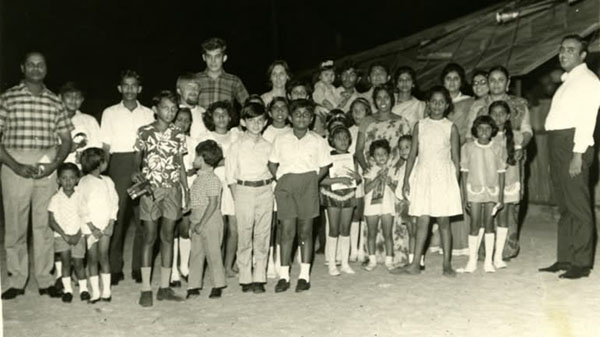

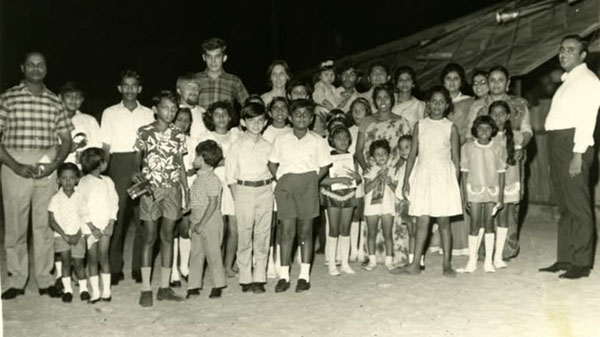

Top: The Sally-Salih extended family and friends at the fourth birthday party of the author’s brother Reyaz. Mount Lavinia beach, September 1972. Bottom: The victory memorial at Kilinochchi. The Sri Lankan Army’s victory over the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the north in 2009 brought the civil war to an end. (Photo courtesy of Razeen Sally)

Many things reminded me of childhood. Even so, I felt I was on a journey of fresh discovery, seeing Sri Lanka for the first time. I discovered a special love for its back-of-beyond places in all their stunning, wondrous variety of people, fauna, landscapes, and coastlines. I cannot think of anywhere else of comparable size that rivals Sri Lanka in this regard. These are places of space and fresh air, calm and silence, peace and contentment.

On my road trips in the war-scarred north and east, I saw a gradual return to peacetime normality. The densely packed Muslim towns on the coastal strip south of Batticaloa heaved with commerce. The main roads were new and smooth, as they are elsewhere on the island. Railway connections had been restored. War refugees were resettled in donor-built housing, and electrification had reached remote villages. But the psychological scars of war will take the longest to heal, if they ever do.

In my years of absence, when I thought of Sri Lanka, my mind wandered invariably to the hill country with its thick green carpets of tea undulating their way across the central highlands. My father was born and bred in Badulla, a hill station in Uva province. I spent my school holidays at “Razeena,” a little tea estate my uncle had bought, about an hour’s drive from Badulla. Razeena was my refuge in the last year of my Sri Lankan childhood when my father was in jail. My mother home-schooled my brother and me on the lawn, next to the lemon tree, I did my homework in the bungalow and wandered around tea trails in the afternoons. So it was with special delight that I rediscovered the hill country, even returning, bittersweetly, to Razeena, now almost unrecognizable, going back to the jungle, its bungalow falling apart at the end of a driveway too rutted for vehicles to pass.

To return to where I began: Sri Lanka’s essentially paradoxical nature. The more I traveled, the stronger my impression became of a smallish country layered in baffling complexity, a light-and-dark, heaven-and-hell country convulsed and consumed by its own extremes. But I also discovered this was not new.

Sri Lanka’s story is blood-spattered, from royal massacres in the ancient Sinhala kingdoms, punctuated by frequent South Indian invasions; to Western colonization, in particular the orgiastic violence of Portuguese conquistadors, to the post-independence present. Yet ethnic mixing and religious tolerance, indeed syncretism, have been a great feature of this history. Sinhala kings had South Indian consorts, imported Tamil Brahmins, mercenaries, and craftsmen, and incorporated Hindu rituals into their Buddhist practice. To this day, Hindu and Mahayana influences suffuse Theravada Buddhist devotion on open display in temples all over the island.

Top: The Lilliputian stupas at Kanthorodai, Jaffna peninsula, December 2011. Bottom: The Colombo skyline across Beira Lake, with the Lotus Tower in the foreground, December 2018. (Photos courtesy of Razeen Sally)

Then there is the multicultural cocktail that comes from an age-old maritime trading heritage. Sri Lanka, halfway between the ancient trading hubs of the Arabian (or Persian) Gulf and the Southeast Asian archipelagoes, was once the Clapham Junction of Indian Ocean trade; and trade brought migrations, particularly of Arab and Tamil merchants. But this extraordinary cultural hybridity did not go unchallenged. Sinhala nationalism was hitched to a Buddhist revival in the twentieth century, which, after independence, led to a political program that became supremacist, chauvinist and racist.

But bigotry is not exclusive to Sinhala Buddhism. Elite Christians displayed it in colonial times; Burghers claiming Dutch ancestry were notorious for it. It finds its echo in the caste-riven, self-isolating Hinduism of the Jaffna peninsula. More recently, another echo comes from a fundamentalist minority in the Muslim community.

Another historical legacy is a fatal complacency, born of the natural bounty of the “wet zone,” which covers most of the island where the Sinhala-Buddhist majority live. Complacency has poisoned post-independence politics most of all. Sri Lanka has had a disastrous political elite of all party colors. First, the over-Westernised, deracinated “brown sahib” dominated it. By the 1980s, the coarse Sinhala Big Man had taken over, exploiting deep traits in a strongly hierarchical Sinhala culture that yearned for a kinglike figure, a charismatic guardian and savior, like the Sinhala kings of yore. The Rajapaksa brothers, Mahinda and Gotabhaya, who rule Sri Lanka today, are its most potent embodiment.

For all its dark sides, I discovered how Sri Lanka, after a long absence, pulled me back and drew me in. I discovered my love for it, warts and all. I want others too, both Sri Lankan and foreign, to venture out of Colombo and outstation bubbles to myriad back-of-beyond places where they will experience a different Sri Lanka. I want them to be awed and inspired by its unique natural cornucopia. And to encounter some of those Sri Lankans, with their spontaneous grace, warmth, and hospitality, who show the country’s better human face.

Razeen Sally is author of “Return to Sri Lanka: Travels in a Paradoxical Island.” He is also a visiting associate professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.