The Colombo Chetties of Sri Lanka : Three Essays – By Michael Roberts

Source : thuppahis

I. The Colombo Chetties of Sri Lanka by Shirley Pulle Tissera

The Colombo Chetties form an integral part of Sri Lankan society. They are a separate ethnic group different from the Tamils, Moors, Malays, Burghers, and the majority Sinhalese community. In the census of 1946 (Vol I Para I) the Superintendent of Census, Mr. A.G. Ranasinghe, states that the Colombo Chetties must receive mention in a racial distinction of Ceylon. The term does not include the Nattukottu Chetties who have formed themselves into a guild for carrying on business in Ceylon and are only temporary residents of the Island.

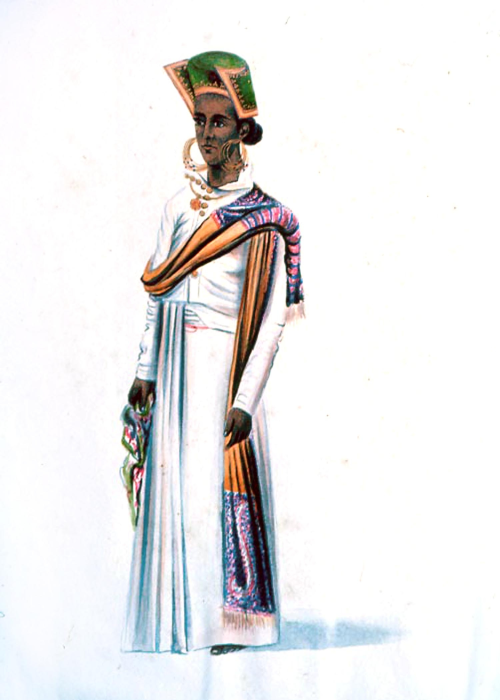

Colombo Chetty –a representation painted by Hippolyte Silvaf in the 1840s or so **

Origin: The Colombo Chetties belong to the Tana Vaisya Caste. The Vaisyas compose nobility of the land, and according to the classification made by Rev. Fr. Boschi, were divided into 3 distincts tribes or castes. The highest sub-division being the Tanya Vaisya or merchants followed by Pu Vaisya or Husbandmen and Ko Vaisya pr Herdsmen. The Tana Vaisyas are commonly called Chetties. Their earliest ancestors inhabited Northern and North Western India near Coorg and Benares. In the eleventh century they were driven to the South of India by the conquest of Muhammad of Ghazini and settled in places like Nagapatnam, Tanjore, and Tinnevelly. It is from here that they traded with Ceylon from the Malabar and Coromandel coasts.

The present day term Chetty is identified with the original term Sethi in Pali, Hetti or Situ in Sinhalese. This is how the community is recorded in history. There is an association of the term Hetti in Sri Lankan nomenclature in names like Hettiaratchi, Hettigoda, Adihetty, Paranahetti, Hettige, Hettigamage, Hettipathirana, Hettihewa, and Hettimulla. A nursery rhyme used a play by children down the centuries has reference to Chetties and their connection to royalty, “Athuru Mithuru Dambadiva thuru, Raja kapuru Hettiya, Alutha gena manamalita haal pothak garala…”

According to Professor H. Ellawala (Social History of Early Ceylon), Sethis first came to Sri Lanka just after the arrival of Vijaya and his followers. The account goes on to show that some maidens sent to Lanka by the King of Madura at the request of Prince Vijaya were Sethis (Vaisya Stock). In the same edition Professor Ellawala goes on to state that Prince Sumitta and his seven brothers who came to Lanka to guard the sacred Bo Tree were sons of a Deva Sethi from Vedissa City in Avanthi. Therefore their sister (Queen of King Asoka and mother of Mahinda and Sangamitta) was also a Sethi.

Reference is also made in Prof. M.B. Ariyapala’s Society in Medieval Ceylon, to Setthi’s participation in the inauguration of kings in ancient Ceylon. (C.M.Fernando JRASCB Vol XIV No.47 Page 126). In an article in the same edition a comprehensive write up is given of Setthi’s (page 104). It also refers to Setthi’s during the time of Vijayabahu I (CV 59.17)

The Nikaya Sangrahaya (ed Kumaratunga), the Madavala rock inscriptions refers to a high official by the name of Jothy Sitana who set his signature to a grant of land.

In the year 1205 AD there existed a minister of great influence among our forebearers named “Kulande Hetti”. His name is engraved on a rock in Polonnaruwa.

The Gadaladeniya slab inscriptions of the 16th century mentions Situ in a list of officials. The Political History of the Kingdom of Kotte (1400-1521) by Dr. G.V.P. Somaratne (page 51) states that the Alakeswara family of Kotte originated from Setthi stock.

In the book titled Culture in Ceylon in Medieval Times by W. Geiger (page 110); “A prominent part of the mercantile society in Ceylon were the Setthi’s but we do not get a clear notion of their social position, probably they were like the Setthi’s in the Jatakas (ref R. Fick 1.1 pages 257) the great bankers and stood in close proximity to the Royal Court.”

Of the three brothers who rebelled against King Wijayabahu I, one was Sethinatha, a chief of the Setthi’s, since the other two were court officials of the highest rank, the three were evidently Sinhalese noblemen (59.16.69.13). Sethinayake is the name of Lambakanna. It was probably his title.

The Mahavamsa Vol III records the arrival in Ceylon of seven sons of King Mallawa of Mallawa Rata accompanied by Chetties who carried suitable gifts for the King of Ceylon. In return the King bestowed titles and also grants of land engraved on slabs in villages such as Kelaniya, Toppu, Ballagala, Bottala, Hettimulla etc. marked out and granted free from duties “to remain as long as the sun and the moon endure”. Among the Chetties who presented gifts to the Kings were Epologama Hetti Bandara and Modattawa Chetty. The donors were honored with titles such as Rajah Wanniah, Rajaguru Mudiyanse and Mallawa Bandara.

The late President, His Excellency J.R. Jatawardena’s first paternal ancestor was a Colombo Chetty. In the mid 17th century one of his male ancestors married a Sinhalese by the name of Jayawardena from Welgama, a village near Hanvalle, and from that time took the name of Jayewardena according to his biogrpahy written by Prof. K.M. de Silva and Howard Wriggins. The mother of his grandchildren is also a Colombo Chetty.

Religion: The Chetties were a community dealing in trade and commerce and would naturally see the advantage of adopting the religion of the rulers. Being a cultured and educated community, the colonisers found a useful link between themselves and the indigenous population, although many prominent Chetty families during the eighteenth and nineteenth century were converted to Christianity.

Many Churches were built by the Chetties. The Church of St. Thomas was built in 1815 facing the Colombo Harbour by the Protestant branch of the Chetties. It is traditionally maintained that St. Thomas the Apostle preached here on his journeys to preach the Gospel on his visits to the Malabar and Coramandel coasts.

Dress Code: Some of the dress of the Colombo Chetties was aptly described by John Capper in his ‘Sketches of the Old Ceylon“. He wrote that they appeared in peak cornered hats, short jackets, cloth and slippers or jutas. They had rings in their ears. Another picturesque description was by L.P. Leisching in his “Account of Ceylon”. He described the educated class of Colombo Chetties of older times who were mostly employed in Government Services as wearing a neat dress consisting of a curiosuly folded turban of white cloth, a short bodied and full skirted white coat and white trousers with a silk handkerchief or scarf around their necks with socks and shoes. This was their regular costume. On important occasions they appeared in gold trimmed turbans and shawls and very rich material for their suits.

The Colombo Chetty ladies of that period were very conservative in their apparel and dressed gracefully without exposing their limbs. Their original dress consisted of a sort of cloak (Sarasa) worn over the head. t was very heavily starched abric of bluish black or deep reddish brown colour. The “Sarasa” had an overall printed floral pattern also of a very dull colour edged with a border of the same colour. The blouse was of white cotton or could be lace on a special occasion. The sleeves were three-quarters length with cuffed ruffs or edged with lace. They wore a camboy or cloth of similar color as the “Sarasa” which had a decorative weave of gold or silver thread for special occasions like weddings. They wore no shoes but had ornamental rings on their toes. The neck was decked with gold ornaments. They wore a chain called “Arriyal” with a jewelled pendant called “Padakkam”. The married ladies wore the “Thali” different in design to the ones worn by married Tamil ladies. Their ears were pierced both on the upper and lower parts. The “Koppu”, a coin like ornament adorned the upper part and the lower lobe with earrings called “Thodu”.

II. “Carving a niche with a distinct contribution” — a review of “History of the Colombo Chetties,” edited and compiled by Deshabandu Reggie Candappa, by Anne Abayasekara

In the mosaic that forms the Sri Lankan nation, we are privileged to have – apart from the two major communities of Sinhalese and Tamils – several small ethnic groups who have made their own distinctive contribution to the country. Most of us are aware of the term “Colombo Chetty” but are rather vague as to who the people are and to whom it applies. Since this community has intermarried with both the Sinhalese and Tamils and since some of them have adopted Portuguese names during the Portuguese period here, there has been some confusion in identifying them.

It was due to representations made to the Government by the Sri Lanka Chetty Association in 1983, and prolonged deliberations held between the Ministry of Home Affairs and a delegation from the Colombo Chetty Association, that the Colombo Chetties received official recognition as a distinct ethnic group on January 14, 1984. This was announced in a Govt. circular “which also ensured that thereafter Chetties will be registered as such in all Govt. documents.”

I gleaned all this from the excellently produced and informative book, “History of the Colombo Chetties” that was published in December, 2000. Those of us who are comfortably ensconced in the majority communities are often insensitive to – or unaware of – the struggle that small ethnic groups may have in gaining recognition as a separate entity within the larger framework of a nation. Books such as this one give us the opportunity to learn about the traditions, culture and customs that are unique to one particular group of whose identity we may have been in ignorance. As a child growing up in my ‘home’ village, I heard the term “Hetti” used and thought it applied to Indian traders. Now I gather that the term Chetty is interpreted as Setthi in Pali, Hetti or Situ in Sinhalese, Etti in Tamil and that in all historical records Colombo Chetties are referred to as Setthi or Situ.

The book is lavishly illustrated with interesting photographs, both ancient and modern. The frontispiece of a Colombo Chetty gentleman in traditional garb – peak cornered hat, bangle-like rings on his ears and a silk scarf loosely knotted round his neck – is very impressive. The back cover is adorned with a somewhat amusing (to modern eyes) sketch of a Colombo Chetty shown full-length in flowing attire and pointed slippers and carrying a distinctive kind of parasol, taken from a series of sketches of “The Sir Lankan Law Court Types” executed by Van Dort. Illustrious members of the community and some well-known families – the Chittys, Alleses, Muthukrishnas, Perumals, Vidurampulles and Candappas are featured.

The Editor has also reproduced one of the late E.C.B. Wijeyesinghe’s delightful articles in his series “Of Men and Memories”, entitled ‘The Story of a King’. Written in his own inimitable style, E.C.B. relates the old story that one of the Three Kings who followed the star to the stable in Bethlehem where the Christchild lay, came from the East and that legend has it that he was a Colombo Chetty by the name of Perumal-“not a common or tea-garden Perumal, but an Ayyam Perumal whose offsprings are found in executive suites in many parts of the World.” ECB goes on to say that there have been many claimants to this role among the Chetties, among whom are the Candappas, Anandappas, Aserappas, Rodrigopulles, Casie Chettys, Alleses, Fernandopulles, Brittos, Babapulles, Ondaatjes and Cadiramens. Colombo Chetties weren’t confined to the capital city but spread their roots in other parts of the island and for the record there are clear group photographs with captions, of Chetties of Dankotuwa, of Thoppuwa, Welihena and Puttalam.

To pick a few notables at random from the long and impressive list compiled here, there was Dr. Michael Ondaatje (not to be confused with today’s famous author of that name who must be one of his descendants). This eminent physician came to Sri Lanka in June 1659 on the recommendation of the Maharajah of Tanjore to attend on the wife of the Dutch Governor Van de Mayden who was stricken with a rare disease that had baffled both Dutch doctors and native ayurvedic physicians. She responded to his treatment and the grateful Governor not only rewarded him with money and jewels, but appointed Dr. Michael Juri Ondaatje the first Doctor of Colombo, the first Colombo Chetty to hold this post. He died in Colombo in 1714.

The late President J.R. Jayawardene’s first paternal ancestor was a Colombo Chetty and there is an excerpt from the biography of J.R. authored by Prof. K.M. De Silva & Howard Wriggins, in support of this. Don Adrian Jayawardene, J.R.’s paternal great-grandfather, descended from a Chetty family, but two or three generations earlier, a male of this family had married a Sinhalese by the name of Jayawardene from the village of Walgama near Hanwella and had taken on the name of Jayewardene and by the time Don Adrian arrived on the scene at the tail-end of the 18th century, “the process of ‘Sinhalisation’ of his family had been completed.”

In a community well-known for its Christian (particularly Roman Catholic) links, and for the many priests and nuns it produced, it may be news to some, as it was to me, to learn that the Ven. Soma Thero of Vajirarama Temple, Bambalapitiya, and founder of the German Dharmaduta Society was born Victor Pulle, the son of Colombo Chetty parents. Many illustrious names are mentioned , among them: E.C. Alles, the first Colombo Chetty to obtain the F.R.C.S (England), and one-time President of the Ceylon Medical Association; George Chitty, Q.C., Justice M.F.S. Pulle, Justice Christie Alles, George Candappa, P.C., Chevalier L.A. Perumal, Dr. Christopher Ondaatje, CEB, financier & philanthropist, who has written the foreword to this book; Mano Muthukrishna-Candappa, Managing Director of the Polytechnic and much else besides Abraham Peter Casie Chitty, an outstanding businesman of the early 20th century. This should suffice to show how members of the Chetty community have made their own unique contribution as citizens of Sri Lanka.

The preface to this book contains a quotation from a speech made by Sir Herbert Stanley, KCMG, Governor of Ceylon, when he addressed the students of a college in Colombo in January 1928. I cannot refrain from reproducing it here because it sounds almost tailor-made for us in the tragic position in which we find ourselves today. These are the words that Governor Stanley spoke 73 years ago and they sound prophetic.

“If the communities preserve their own traditions and are prepared to put into the common stock the good which they have inherited from their ancestors, there is every hope that we may build up, here in Ceylon, a happy and united Ceylon; ……. by our common devotion to Ceylon and our common desire to make her a better country for our children, than she has been for our fathers.” I say ‘Amen’ to that

III. “The Colombo Chetty community,” A Review by Manel Ratnatunga, Island Features 27 Jan 2002

Do you want to know who the Gratiaen Award Ondaatjes are? From where did they come, and who married who, and who are their children? Our mothers’ generation would have revelled in a book such as this and would have spent many delicious hours discussing what ATS Paul has written in this marvellous WHO’S WHO about the Chetties. For us today, a wonderful font of knowledge about a very vibrant community of our nation.

Names we have all heard – the Muttukrishnas, Aserappas, Casie Chitties, Pauls, Fernandopulles, Candappas to name a few are all here in a scintillating run of their dazzlingly brilliant achievements along the generations.

The first Ceylonese Medical Officer of Health; Founder President of the Association of Surgeons of Ceylon, who achieved the rare distinction of obtaining both the Membership of the Royal College of Physicians and the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. The first Ceylonese Director of a British Company (Lewis Brown) rising to be its Managing Director; the first Ceylonese to be a member of the High Court of Justice of the Netherlands; first to act as Crown Counsel; first to import an automobile and an air conditioner; first to introduce neon advertisement (Berec ad. on top of the Savoy Cinema). A Chetty was admitted into the Colombo Club for Europeans only. Then there is Lady Corea. Do you know who her father was? And who was Mabel, the patron of Bishop’s College? And who, the lovely Vanaruha?

ATS Paul, the surgeon, writes with the precision of his surgical skill. Neat, tidy, precise. He tells that Chetty merchants were visiting Ceylon in their own sailing vessels carrying diamonds from Golconda, emeralds from Rajasthan, rubies from Burma and so on from various states of India from pre-Buddhist times. Their arrival here is documented in our history during the time of King Rajasinghe II and the governorship of the Dutch. Once they settled in Ceylon, these traders and money-lenders dropped out of the money-lending livelihood as it was considered repugnant and switched to the learned professions where they rose to great heights of fame.

We learn that the Chitty legal luminary, who owned one of the first imported automobiles, used a rickshaw to go from his home Stafford House to the Supreme Court. That his son drove the family American carriage drawn by an Australian horse to Royal College at about the age of ten. ATS has not explained why their neighbors objected to this. All his children were educated at home and the boys went straight into Form 1 at Royal College and walked away with many prizes.

The book takes you on a romp through Colombo when fields and forests lay beyond Pettah and the Fort, from where a wild elephant might emerge. Do we know Pettah was originally Jampettah and why? And that it was just a village street owned by the Colombo Chetties. And why ‘Colombo’ Chetty? How did that name come into being? I must admit I never knew half these interesting facets about a clan of people who have made great contribution to our nation and belong with pride to Sri Lanka. This easy to read compilation is a MUST for our public and private libraries.

A Note: in my evaluation the first article by Shirley Pulle Tissera is an interesting read, but something of a pot pourri which presents legends, fables and facts in a mix composed haphazardly without much ordering. It stimulates but does not guide. It includes details which may not relate to the Colombo Chetties as a community as we know them — dating say from Dutch times. If someone can show me that they were an identifiable collectivity, both in their own estimation and in the understandings of articulate and powerful others (Portuguese, Sinhala kings and elites) in Portuguese Ceilao, then, I stand corrected. Michael Roberts