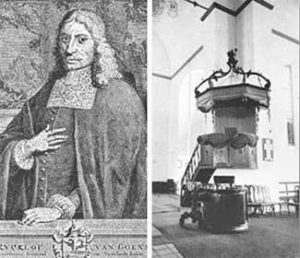

(Photo on left is of the interior of the church with the pew and baptismal font and a glimpse of the old Dutch chairs against the wall in the background. On the right is portrait of Dutch Governor Ryckloff Van Goens)

Source: Sunday Island, October 1, 2017

That almost neglected but historic building in the Pettah, the Wolvendaal Church, is unique in many ways. It is one of the few buildings in Sri Lanka which link the Portuguese period of occupation of Sri Lanka right through the Dutch, and British periods, to independent Ceylon, and finally exists as a repository of culture of the Dutch who unsuccessfully sought to conquer the whole country. Some recent photographs show weather related damage to the exterior of the building, which seem to be receiving the attention of those who are in charge of

The Dutch made their presence in Ceylon in 1640 with the capture of the Fort in Galle from the Portuguese. Within the next few years they took control of the maritime provinces and began erecting churches to propagate and foster their religion as propounded by the Reformed Church of Holland. In the early days of Dutch occupation, the official church of the Dutch in Colombo was located in Gordon Gardens. It was an old Portuguese building which was in need of repair, and a proposal was made by Governor Van Imhoff to demolish it and erect a new one. It was a few years later in 1743 that the Governor Stein Van Gollenese decided to build a new church and chose Wolvendahl as the site. It has been claimed that there was a church built by the Portuguese pre-existing on the site, dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe, a name corrupted by Sinhalese usage to Adilippu and further corrupted by the Dutch to Agoa de Luphe which means “the dale of Wolves” and hence the name Wolvendaal. Wolves of course have never existed in Ceylon. Yet another connection with the Portuguese era relates to the bell at Kayman’s Gate (the belfry of the Wolvendaal Church) which is considered part of the church. The bell was originally hung in a Roman Catholic church in Kotte, and after the abandonment of Kotte by the Sinhalese kings it remained there until it was removed to Kayman’s gate.

The new church was dedicated to public worship on March 6, 1757 by the Rev Matthias Wirmelskircher in the presence of two Dutch Governors Gideon Loten and Jan Schreuder , the former just having relinquished office as Governor, and the latter just taken over from him. The efforts of Van Gollenese were not forgotten and the letters JVSVG representing the name Julius Valentyn Stein Van Gollenese etched into the gable over the southern entrance to the church remains to this day. The date 1749 displayed over the doorways have been confirmed as the year in which the foundation stone was laid. When Bishop Heber visited Ceylon in 1825 he attended a service at the Wolvendaal Church at which the Colonial Chaplain Rev Johan Henricus de Saram preached a sermon in Sinhalese.

Although the building took eight years to complete it has stood the test of time providing succour and divine guidance to thousands of faithful devotees throughout its 260 years of existence. Conceived in the Portuguese era, born during the Dutch era and having served right through the British era into the days of Republican Sri Lanka, the history of the church is not without its share of controversy. Up to the time of the British conquest, many of the Sinhalese families in Colombo had converted to Christianity as propounded by the Dutch Reformed Church and attended the Wolvendaal Church. Many of these families however switched allegiance to the Church of England after the British conquest of Ceylon, a matter which was looked down upon by those in charge of the Wolvendaal Church. Rev JD Palm was the Minister in charge of the church and under his edict the Sinhalese Colonial Chaplain was not allowed divine services in Wolvendaal. Rev JD Palm had been described as behaving with “heat and insolence” to the Sinhalese proponents as reported by Rev G Bisset and confirmed by Mr TJ Twistleton, Chaplain to the Government. Palm’s intransigence led to a protracted controversy between Palm (who was a German by birth and not of Dutch origin) and the Dutch elders of the Church on the one hand and the Sinhalese proponents on the other. Mudaliyar Don David Alwis a Sinhalese Chieftain of the day was to be married to the daughter of Samarakoon Mudaliyar and they sought to have the ceremony in the Wolvendaal Church but Rev Palm refused permission. Dr Twistleton however obtained an order from the Government directing Rev Palm to provide the Church for the marriage and service. The service was conducted in Sinhalese by the Rev Andrew Armour and the matter resolved .This episode raised some concern and matters came to a head when it was referred to the Secretary of State for the Colonies Earl Grey, who finally upheld the findings of the Governor Colin Campbell. The controversy and the deadlock created dissension for a period of about six years until it was finally settled in 1851.It was held that church belonged the to the consistory and that the government has no role in its administration.

Despite the fact that the church was open for service in 1749 all the deceased Dutch Governors right up to the time of capitulation to the British in 1796 continued to be laid to rest in the Dutch Church in the Fort. Governors who were buried in the Fort Church including those who officiated prior to the building of Wolvendaal were Gerritt de Heere (1702), Isaac Rumph (1723), Johannes Hartenberg (1725), Gerard Vrealand (1752), Lubbert Van Eck ( 1765), Iman Falck (1785), Joan Van Angelbeek (1799) and of course the doughty Dutch hero Gerard Hulft who died in the siege of the Colombo Fort when it was occupied by the Portuguese. On September 4, 1813 the remains of the Dutch Governors were removed and interred in the Wolvendaal Church in an official ceremony involving the Dutch community and the Government of Ceylon, conducted with pomp and pageantry befitting the status of the deceased Governors. The remains of King Dharmapala (the only Sinhalese king to convert to Christianity) who died in 1607 were also buried in the Fort Church and removed to Wolvendaal in 1813.His tombstone with a Portuguese inscription is also believed to have been transferred to Wolvendaal, but there is no trace of it now. A similar fate seems to have befallen the tombstone commemorating General Gerald Hulft. It has since been suggested that Hulft’s tombstone was later used to commemorate the life of Sir William Coke, Chief Justice and was placed in St Peter’s Church in the Fort with the Hulft inscription on the obverse.

In 1938 the renowned antiquarian, the late RL Brohier, published a souvenir of the church giving it a Dutch title “De Wolvendaalsche Kerk”. The text was both in English and Dutch accompanied by some excellent photographs of the exterior and interior of the church by master cameraman Lionel Wendt. Some of the photographs used here are from this publication

Architecture and interior of the Church

While the style of architecture is Doric, the building is shaped in the form of a Greek cross. The lofty domes stand tall and in bygone years was a landmark for mariners to steer their ships into the port of Colombo. The church has a seating capacity for 1,000 worshippers.

There are many interesting memorials of Dutch rule in this historic building among which are the coat-of-arms and tombstones of Dutch Governors removed from their former place of rest in the Gordon Gardens. One of the elegant stained glass windows in the church was a gift of Governor Sir William Gregory and another that of Mr WH Wright. Yet another was erected by public subscription as a memorial to Sir Richard Morgan. Others were erected by Government grants, two being to the memory of a Mrs Raymond, and a Mrs Schroter who were munificent donors to the church.

Below the pulpit are the baptistry and the lectern. The baptismal basin is two feet in diameter and made of pure silver. It rests on an exquisitely carved ebony tripod gifted to the old Dutch church in the Fort by Dutch Governor Rycloff Van Goens over 400 years ago. An inscription on the tripod states that the font and stand were gifted to the church to commemorate the christening of his daughter who was named Esther Ceylonia. The mother Esther born in 1640, second wife of the Governor, died the day after her infant daughter was baptised on June 22, 1668, and the tombstone to her memory and to that of the Governor’s first wife is a beautifully sculptured monument placed against the outer wall of the church, presumably transferred from its original location in the Fort.

There is also a remarkable collection of Dutch furniture mainly chairs made of ebony, calamander and nadun wood which reflect the consummate skills of the Dutch cabinet maker. When I visited the church in about 1960 the chairs were hidden away in a storeroom presumably for “protection” against thieves, but we sincerely hope that these have since been displayed for the pleasure of the public and to remind today’s Sri Lankans of the skills that were evident in the country nearly four centuries ago. According to Brohier there seemed to be a custom in days gone by, for church goers to keep their own chair in the church for use for service on Sundays by the owner, and he speculates that some of the chairs may have been transferred from the old Dutch Church in the Fort.

While the first Centenary of the Church was celebrated 1n 1849 with pageantry that befitted its origins and antiquity, the second Centenary in 1949 seemed to have passed by unnoticed and unsung. Just 32 years more for its third centenary, and let us all hope that the remaining proponents of the Dutch Reformed Church now functioning as the Christian Reformed Church (with a congregation from a multi ethnic and broader base) will have this important anniversary well in hand.

No Comments