CULTURAL VANDALISM SHOULD BE ERADICATED ! – By HUGH KARUNANAYAKE

Sri Lanka is a country with a recorded history of over 2500 years. Few countries in the world could match that record. A nation’s history brings with it a certain accumulation of historical facts, culture, customs and manners which combine to provide contemporary society with a base that is inspirational and serves also as a platform for a unique understanding of our environment. Unfortunately, over the years there have been many elements from within our own society, who either under estimate the value of a sophisticated culture or allow mercenary instincts to dominate their thinking. There are many recorded instances of cultural vandalism in Sri Lanka, and I focus on two examples that should serve to highlight the extent of the problem, and the need to take effective action.

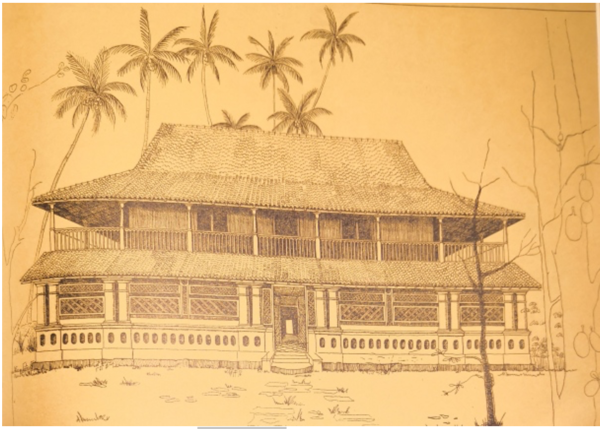

The unfortunate ending to “Mill House” in Gintota is the first example of cultural vandalism, that I would like to discuss. This two storied imposing building was built probably in the mid 1 9th century era during the tenure of Governor Barnes, the third Governor of British Ceylon. Governor Barnes is more likely to be remembered for the patronage he provided to Thomas Skinner who is recognised as the country’s pioneer road builder opening up the hinterland of the country by a network of roads to provide access to the country’s future plantations. With the unexpected decline of coffee, Governor Barnes was seeking to replace it with sugar cane among other crops. He encouraged the migration into Ceylon by successful sugar cane planters from the Mauritius. Families headed by names such as Vander Poorten, Bowman, Northway, Winter, Gottelier, Hearst, moved into Ceylon and were provided opportunities for developing the crop. In fact Governor Barnes himself invested in a property in Gannoruwa. Although sugarcane as an agricultural crop did not succeed in the higher elevations, it seemed to have had some traction in the Baddegama area where the Bowmans and Winter families decided to put down their roots. The crop went together with a sugarcane factory situated on the banks of the Gin Ganga, at Gintota. The large two storied mansion the home to the pioneer planter was created according to traditional Sinhalese design as the residence of the proprietors, and was called the Mill House. For most of the early part of the Twentieth Century, Mill House was occupied by HCR Anthonisz of Dutch heritage, and a senior official of the Excise Department. It was subsequently owned by a family of traders from the South who ultimately presided over its demise.

The traditional design of Mill House had evoked the interest of such enthusiasts of traditional Sinhalese architecture as Geoffrey Bawa, Ulrik Plesner and Barbara Sansoni.

In fact Barbara Sansoni featured the house in her book Vihares and Verandahs. She admired the building so much that she had taken many overseas architectural enthusiasts to view the building which was famous for its indigenous style and design. On one such visit she found that the building was demolished and the last owner living in another house nearby. When she remonstrated with the man for destroying a historic building merely to make some money out of the timber structure, his response was not only revealing in its lack of appreciation of centuries of architectural splendour, but also the bluntness in his message. His response to Barbara was “ Well you came here, took photographs of my house, and probably made money out of your story, while I who owned the house languished in poverty!. It was my turn to cash in “. The story seems to highlight two aspects of the issue. One, the need for legislation to protect antiquities from destruction, and two, the need for a state sponsored fund to adequately recompense owners of heritage listed buildings.

“MILL HOUSE “ GINTOTA

(Drawing from the Architectural Review V ol 139, number 528, February 1966) The demolition of the old Dutch Church at Bentota is yet another example of cultural vandalism, this time by a government elected by the people !Although the building was originally a church built in 1755, it was from early British times used as a government school until the building itself was demolished in 1991, to give way to a modern school building which now exists in its place.

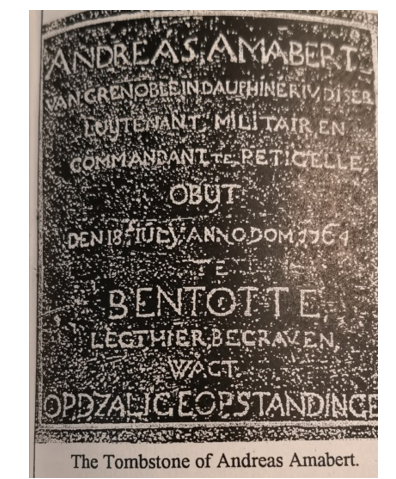

The old building and its associated inscriptions were the subject of several articles that appeared over the years, in many learned journals published notably the Ceylon Literary and Antiquary Register ( non- existent now), the journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, and the Journal of the Dutch Burgher Union, alas, also defunct now. Much of the interest shown was due to the fact that the church built in 1755 contained another monument, the tomb of Andreas Amabert who died on 18 July 1764 at Bentota. The tomb was located in the centre of the building and bore an inscription in Dutch shown in the illustration, based on a photograph taken in 1877 by Mr HCP Bell, who was then Police Magistrate at Balapitiya.

The translation reads” Andreas Amabert born at Grenoble in the River Isere Dauphini, Military Commandant at Pitigala, who died on the 18 th July AD 1764, lies buried here, in the hope of the glorious resurrection.”

Andreas Amabert was a French soldier in charge of the minor Fort built by the Dutch in Pitigala, located east of Bentota, and serving as a northern outpost of the Southern Command based at Galle. Amabert was stricken with an illness in May 1764 and was transferred to Bentota for treatment where he died two months later. HCP Bell writing in the 1915 issue of the Ceylon Antiquary and Literary register stated “ At no period would the enclosing of the stone which covers this solitary grave be more appropriate than now, when British and French are fighting shoulder to shoulder as Allies in a life and death struggle against modern powers of darkness.” Unfortunately, Bell’s advice went unheeded, but became truly prophetic as the “powers of darkness” crept over the tomb of Andreas Amabert in the form of a governmental edict issued in 1991 ordering the demolition of the building which housed Amabert’s mortal remains.

Thompson Van De Bona writing in the Sunday Observer of September 1999, wrote” At a recent visit to my village after a lapse of about 25 years, I found many changes there, most of which not only surprised me but made me feel ashamed of myself and the rest of the villagers. I found that the old church building built by the Dutch in 1755 in which my old Sinhala school was housed, was no more. The building was ordered to be demolished by the Education Department, and a private contractor had not only done it, but had removed everything of the building from the site, including the historical monuments. I was informed by the villagers that when the tomb was dug they had found a set of gold cuff links and some gold buttons by the side of the skeleton, but nobody knows what happened to those findings”. The young French soldier laid to rest in a lonely grave in a distant land away from friend and family, was not allowed to rest in peace ! Need we say more !