The last ride of a Jesuit Priest – By B. Nimal Veerasingham

Greater welfare depends on our Individual and collective actions!

Source: Island

We are currently in the cautious process of passing through an unpredictable portion of our life journey. Like time-travelling through an eclipse, our trekking is through an unchartered territory, where Coronavirus is driving the agenda while people are readjusting their lives accordingly. Science has advanced so much for the better – it tells us how to reduce the impact of this contagious disease, or to protect ourselves from becoming victims.

Almost 100 years ago, things were not the same. Humanity, it is said, has advanced in every scope and spectrum, within the last 50 years, in rapidity, as compared to the 500 years before that period. Between 1918 and 1920, almost a third of the world population; that is nearly 500 million people got infected with the deadly influenza pandemic, with an estimated death toll of 17-50 million. For comparative purposes, the current Coronavirus pandemic has infected nearly 24 million and caused nearly 850,000 deaths worldwide.

The 1918 flu pandemic, popularly known as the ‘Spanish Flu’, has the underpinning of the great blame game that is being played out even now, in certain circles. Thanks to the propagators of the ideological divide – the name ‘Spanish’ was intentionally slung to nullify the neutral position taken by Spain during the 1st World War, which was raging during the same time. The parties to the war, without much evidence, blamed Spain as the culprit and the active incubator of the virus.

The deadly influenza pandemic of 1918 and the extent of chaos and casualties it did inflict, along with the ‘Great War’, might have faded away from the collective memories and recollection of history notes. We are busy facing an equal fear, 100 years later, and thus living in the presence, with no time levitating to the past. Sri Lankans must be proud of the track record, so far, as acknowledged by reputed International agencies, with less than 3,000 infections, by taking adequate and speedy measures to contain the disease, compared to many in the region. Things were not this smooth during the 1918 pandemic, which overwhelmed the country in two distinct waves. The Register-General of Ceylon at that time reported the casualty numbers as 41,916, due to influenza (excluding pneumonia and other complications), mentioning that the flu was raging in the Island during later part of 1918. A study at the Michigan State University put these numbers much higher, from the existing high estimate of 91,600 or 1.1% of the population, to between 307,000 and 313,000 or 6.7% of the population. This is in comparison to the neighbouring India’s causality rate of 5.5% of its population.

The staggering casualty numbers of the 1918 pandemic foretells the suffering inflicted on the people of Ceylon/Sri Lanka, and the world in general. Legally, we may think destruction by nature is an unlawful exercise of physical force. Many will agree in casting the flu-virus as being the originator of such unlawful force; whether such entity has legal standing in the grasps of law or not. Although our collective psyche is to build a peaceful society, reflecting our karmic values, history records great natural mishaps, causing gaping holes in our pursuit towards a Dharmic society. Insurance companies prefer to settle with ‘Act of God’ theory, due to unsettled questions on legality and insurable liability. Nature must be respected and its lessons learnt; science being a stronger interloping interpreter in the equation.

It is almost 16 years since the Boxing Day Tsunami of 2004 wreaked destruction on our people. One of the key recommendations by subject-experts then, was to encourage extensive growth of Mangroves in vulnerable areas, notably in the East. This is not only to limit destruction by violent waters, but also to encourage sustainable marine life, absorb pollutants and limit the damages of Global Warming. In reality, even after 16 years, it is questionable whether there is a systemic effort to follow through on that recommendation.

While growing up in Batticaloa town, we were staying adjacent to the ‘Central Hospital’, managed by late Dr. R. K. Selliah, where my mother worked as a nurse/midwife. We had to move from ‘Puliyanthivu’, the administrative Capital of Batticaloa, where we were born, to ‘Koddaimunai’ North of the ‘White Bridge” that connects both localities. The ‘Bar Road’, signifying its end destination of the ‘sand bar’, where the lagoon meets the sea almost three kilometres away, literally begins where we lived. The house sat on a large parcel of nearly five acres of empty land, with many majestic margosa trees, mango trees and some unusual larger striped versions of house geckos, around. What I observed unusual about this environ was that it had stretches of pure white sandy soil, exactly like the ones you see by the ‘Kallady’ beach facing the Indian Ocean; in density, colour, lightness and depth. On full moon nights, myself and my brother would engage in a friendly wrestling competition, with the soft beach sand providing the cushioning underneath, while our athletic father acted as the referee. It tells us that the Indian Ocean, which is now almost three kilometres away, probably must have been in this immediate vicinity thousands of years ago. The Eastern Technical Institute, a joint venture by the Methodist Church and the Jesuits, to train young people in refrigeration/welding/

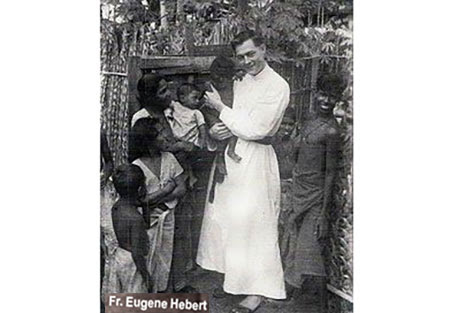

The youth of Batticaloa suffered on many fronts for a long time, notably with the higher rate of unemployment. Even the statistics dept. numbers, as late as 2017, placed the unemployment rate as 6.6%, the second highest in the country. The concept of Eastern Technical Institute was to address that duress in a measurable way; to obtain gainful employment locally or abroad. While it was being built, right from the very laying of the cornerstone, I had the opportunity to witness a mastermind at work. He is none other than Rev. Fr. Eugene Hebert, the Jesuit priest, who arrived from Louisiana, United States, in September 1948, and later became a dominant figure in the game of basketball, helping St. Michael’s College, Batticaloa, become All-Island Basketball champions many times.

He not only oversaw the planning and buildings constructed, but instrumental in manufacturing the main components necessary for the buildings, locally – bricks, iron accessories, wooden frames/beams and roofing. The students who assisted in the building project were paid wages besides obtaining valuable experience in the vocation. It was a familiar sight to see the priest up on the rafter, adjusting the pully to raise the roofing frame; or with the students making bricks, mixing gravel and cement in manual compressors. The same ethics of discipline, training, dedication and leadership that brought basketball championships to the high ground of academical esteem perched down Central Road, Batticaloa, allowed the Technical Institute also to rise from the plain white sand patches, giving hope to the youth of Batticaloa. Fr. Hebert not only supervised and partook in the planning and construction of the Institute but served as a devoted Teacher and Director at the same. It is a normal site in the mornings, witnessing the slightly hunched Jesuit priest with a crewcut and circular eye glasses on thin frame, crossing the ‘Puliyantheevu’ White bridge on his bike, all the way from the Jesuit residence at St. Michael’s College, to the Technical Institute at ‘Koddaimunai’.

The administering of proactive measures and implementing it to the fullest in Sri Lanka by the political and uniformed authorities, has resulted in containing the Coronavirus epidemic, compared to many nations. The lessons learnt from previous epidemics, including the ‘Flu of 1918’ may not have directly influenced the outcome, but through the natural evolution in gaining higher ground through past global experiences and informed readiness. Respecting and learning from the past, along with the help of proven science, has resulted in containing the deadly decease, resulting in safer towns and communities. Upheavals free safer societies are not simply slogans, but an open embracement, attitude and deep belief, whether the villains come in the form of nature or not. Nature cannot be tamed fully, whether it’s a virus or Tsunami – but could be contained with less destructive impacts, when human spirit confronts and takes proactive countermeasures to overcome nature’s unexpected onslaughts.

As we pass through the month of August in acknowledging our moment of defiance against an invisible common enemy, it also allows us moments to reflect on some unfamiliar descents from the past. As an unrelated notation of event, the month of August also stroke our memory on the demise of a Jesuit priest, who travelled thousands of miles from United States, to serve the people here. His sign of determination to provide hope, surpassed all the prevailed dangers of fatal tropical diseases like Typhoid, Malaria and Cholera, that was rife in Asia during the 50s.

The Batticaloa lagoon hides many truths amidst its opaque, non-splurgy waves, while gently reaching the clear marshy shores. ‘The truth will set you free’ – as the scripture says, finding the truth under the periscope of Justice and applying it to the larger reciprocal and collective Dharma of society, in some ways could be compared to applying science in the struggle with viruses.

This August 15th, 2020 marks the 30th anniversary of the ‘disappearance’ of Rev. Fr. Eugene John Hebert.

He was last seen passing through ‘Eravur’, not far from the shores of the Batticaloa lagoon, along with an Eastern Technical Institute student, at the pillion of his scooter. His and his student’s remains were never found, and no one to date has any knowledge of what happened to them. Even on his very last scooter ride towards Batticaloa from Valaichenai, his mission was to help others – restoring electricity in an orphanage run by nuns and bringing them to safety.

‘Listen to the gentle frothy waves of the Batticaloa lagoon’, said the poet. ‘The mangroves have not multiplied in forming a barrier, to have it still’.

No Comments