The life of Negombo’s Oruwa fishermen-BY MAHIL WIJESINGHE

The fishermen just came from the sea

Source:Sundayobserver

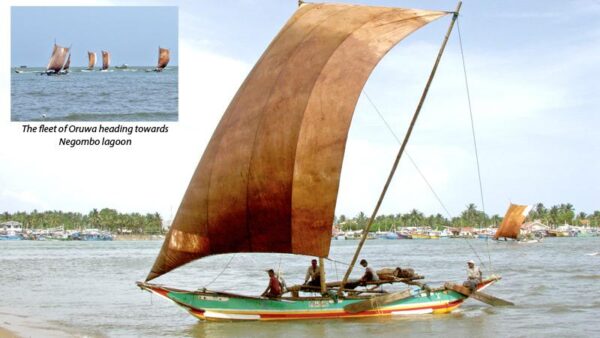

One sunny morning, I was at the Negombo Lagoon to do a photographic essay on the daily life of Karawa fishermen whose Oruwas (sailing boats) take a spectator to a time when man was quite close to the elements and had to battle the forces of nature.

The Negombo Lagoon and Duwa is an ideal place to watch fishermen at work. Each morning, except Sunday, fishermen of Negombo, many of them live in the small island of Duwa across the Lagoon, but connected by motorable causeway, bring their daily catch of crabs, prawns, seer and other fish. Then, they mend their nets on the beach.

The Negombo Lagoon and Duwa is an ideal place to watch fishermen at work. Each morning, except Sunday, fishermen of Negombo, many of them live in the small island of Duwa across the Lagoon, but connected by motorable causeway, bring their daily catch of crabs, prawns, seer and other fish. Then, they mend their nets on the beach.

The principal tool of the trade is the Oruwa, a dugout outrigger canoe which bears similarities to those used in the Comoro Islands off Mozambique, Africa. It has been here in Sri Lanka for a long time. The Roman historian, Pliny, who visited Sri Lanka in the 1st Century A.D., stated that this vessel was a typical sight off the coast of Lanka.

Oruwas can be found along the West coast of Negombo and sometimes can be seen in fleets offshore. Their rectangular sails spread across the horizon like a pack of cards. Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the Oruwa is its method of construction. Except for a half dozen brass bolts used as thwarts, the various pieces of the craft are either lashed or sewn together. The Sri Lankan shipwright literally threads a needle and, stitch by stitch, assembles his craft.

Trawling for prawns

The Oruwa usually trawl for prawns several kilometres offshore, sailing back and forth, as they comb the muddy bottom with a drag net. After each sweep, the catch is dumped on the seashore and fishermen seated cross-legged in the middle of it, sort fish into one basket, prawns into another, while, shells, sea-weeds and an amazing collection of rubbish-bottles, sea snakes and plastic go over the side.

A fisherman brought the Oruwa up into the wind and adjusted the sail so that it shaded most of the boat. Fishermen lay down on the platform, sharing the space with the two crew members, while one fisherman balanced himself on the gunwales and used the mast step for a pillow. The only person left in the sun was an experienced fisherman who tied a bit of cloth around his head as a kerchief, and dozed lightly at the helm, occasionally giving the steering oar a kick to hold the boat in position.

The rest of the fleet followed their lead and soon, within less than a square kilometre of sea, upwards of three hundred men were sprawled across their boats taking a nap. The fishermen slept for about an hour, then one fisherman turned the boat and let the sun wake us up. Once again they untangled the lines and net and threw the weights overboard. After three short drags the wind suddenly veered onshore – time to head for home. The entire fleet turned as if a single hand controlled all the tillers and like a nautical ballet a hundred sails turned towards Negombo.

After the catch is sold, the money divided, the crew pull their Oruwas on to chocks and wash them down with sand and water to clean off marine insects. Oruwa are seldom painted but, once a week on Sundays, they are given a protective coat of coconut oil.

Lifestyle

The fishermen have their own lifestyle. They take life day-by-day. Nobody thinks much of the future. Whatever they make goes straight to the market, but money doesn’t really mean that much to them. When someone dies or gets married they don’t have enough money to have a party for their friends.

So the community helps them. Word goes around that on such and such day everyone will go fishing to pay for a funeral or a marriage. The whole day’s catch, that of may be a hundred boats, goes to the family, and it could thousands of rupees. If the family is lucky, there will be plenty left over after paying all the expenses. It is an old custom and no one knows where it came from.

The Oruwas of Negombo have recently taken on a new importance and attracted a great deal of attention.

The rising cost of fuel has altered the vision of the future, and the fishermen’s dream of standing at the wheel of powerful motor launch is fading. To help lure men away from diesel engines and outboard motors, boatyards that produce glass fibre launches are beginning to experiment with making Oruwa with the same material. Progress is looking backwards, and the traditional outrigger canoe may be the best way for the fisherman to sail into the future.