The Evolution of Sri Lankan Architecture: A Tapestry of Cultural Influences – By Malsha – eLanka

Sri Lanka, strategically positioned in the Indian Ocean, has long been a focal point for travelers and traders due to its critical role along maritime routes. Formerly known as Ceylon, the island has witnessed a continuous succession of invasions, each leaving a distinct imprint on its architectural and cultural heritage. From the incursions of South Indian dynasties such as the Pandya and Chola to the lasting impacts of European colonial powers—including the Portuguese, Dutch, and British—Sri Lanka’s sociocultural and political landscapes have been shaped by these varied interactions.

Buddhism and Early Architectural Development

A deep exploration of Sri Lanka’s architectural heritage highlights the profound influence of Buddhism. Early residential structures exhibited simplicity, utilizing materials such as mud, sticks, and straw, while religious edifices were constructed with durable materials like stone and clay bricks, ensuring their longevity.

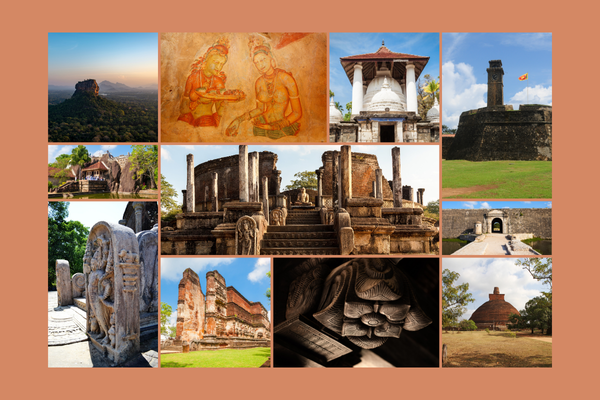

In the island’s formative architectural stages, religious structures were seamlessly integrated into the natural environment, with early builders utilizing stone caves as sacred spaces. This adaptation showcased their exceptional craftsmanship, as they transformed rugged stone into artistic and spiritual masterpieces—comprising intricate statues, elegantly designed staircases, ornamental guard stones, and towering stupas.

Anuradhapura: A Grand Legacy of Buddhist Architecture

The ancient city of Anuradhapura, one of Sri Lanka’s greatest historical capitals, emerged along the banks of the Malwathu Oya River and flourished from 250 BC to 900 AD. Despite brief periods of Tamil dominance and invasions from South India, Anuradhapura became a thriving center of Buddhist culture, home to numerous monasteries and significant religious sites.

Remarkable Achievements in Sigiriya and Polonnaruwa

In 477 AD, King Kashyapa relocated the capital from Anuradhapura to Sigiriya, an imposing rock fortress rising 200 meters above the surrounding plains. Sigiriya’s architectural brilliance extended to city planning, irrigation, and garden design, with its water gardens serving as an advanced example of linear irrigation techniques.

In the early 11th century, the Chola Empire invaded Sri Lanka, leading to the establishment of Polonnaruwa as the new capital. The Cholas, known for their Hindu influences, replaced many Buddhist monasteries with Hindu shrines. Although King Vijayabahu ultimately expelled the Cholas, elements of Hindu architecture persisted in Polonnaruwa’s structures.

The Kandyan Period: Architectural Innovation

By the late 14th century, the power center shifted to the wet zone, giving rise to the Gampola and later the Kandyan Kingdom. This era marked a resurgence in architectural creativity, with the construction of significant temples such as Lankathilaka, Gadaladeniya, and Embekke Devala. The Kandyan period introduced climate-responsive structures, particularly the innovative Kandyan roof, and showcased exceptional craftsmanship in woodwork.

European Influence: The Portuguese, Dutch, and British Eras

Portuguese Fortifications and Cultural Imprint

The Portuguese arrived on Sri Lanka’s shores in 1505 and swiftly established a network of forts and trading posts along the western coastline. Though primarily focused on trade rather than territorial expansion, they introduced Catholicism—often through force—resulting in lasting cultural influences. Architecturally, they incorporated elements such as timber shutters, large domestic windows, squat Tuscan columns, round-arched openings, and half-round roofs into Sri Lankan structures.

Dutch Urban Planning and Architectural Adaptations

In the 17th century, King Rajasinghe II allied with the Dutch to expel the Portuguese. The Dutch reinforced existing forts in Colombo, Galle, Matara, and Jaffna while establishing new ones along the coastal regions. Unlike the Portuguese, who preferred multi-story buildings, the Dutch embraced single-story structures with spacious verandahs, reflecting their adaptation to the island’s tropical climate. Dutch churches in Colombo and Galle remain as testaments to their architectural integration, blending European Baroque simplicity with Asian spatial aesthetics.

British Neoclassicism and Urban Transformation

Following the Dutch, the British took control of Sri Lanka in 1815, becoming the first colonial power to dominate the entire island. Unlike their predecessors, the British pursued large-scale economic transformation, introducing a plantation system that altered the landscape with cinnamon, coconut, rubber, coffee, and tea cultivation. Their administrative ambitions led to the development of roads, railways, and prominent public buildings constructed in a neoclassical style. Unlike the courtyard houses favored by earlier settlers, British domestic architecture leaned towards compact bungalow-style homes with expansive gardens, reflecting their preference for refined dignity over sheer comfort.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s architectural evolution is a rich tapestry woven with indigenous creativity and external influences. From ancient Buddhist stupas and rock fortresses to colonial forts and European-style public buildings, the island’s architectural landscape embodies centuries of cultural amalgamation. This enduring legacy invites scholars, architects, and historians to explore and appreciate the profound artistic and structural achievements that define Sri Lanka’s built heritage.