The halo: A symbol that spread around the world

Courtesy- BBC- Matthew Wilson 24th June 2021

(https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210623-the-halo-a-symbol-that-spread-around-the-world)

(Image credit: Alamy)

After first appearing in the religious art of ancient Iran, the disc halo migrated across cultures at an astonishing pace, aided by trade on the Silk Roads. Matt Wilson explores how a simple symbol connects Jesus, Buddha and Apollo.

Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism and Greek mythology are usually regarded as utterly distinct religions, largely defined by their differences. But if you just look at them, you will see a symbol that connects them all – the halo.

This aura around a holy figure’s head expresses their glory or divinity and can be seen in art across the world. There are many variants, including rayed haloes (like that on the Statue of Liberty) and flaming haloes (which feature in some Islamic Ottoman, Mughal and Persian art), but the most distinctive and ubiquitous is the circular disc halo.

Why was this symbol invented? It has been conjectured that it could have originally been a type of crown motif. Alternatively, it may have been a symbol of a divine aura emanating from the mind of a deity. Perhaps it was a simple decorative embellishment. One amusing proposal was that it derived from protective plates fixed to statues of gods to protect their heads from bird droppings.

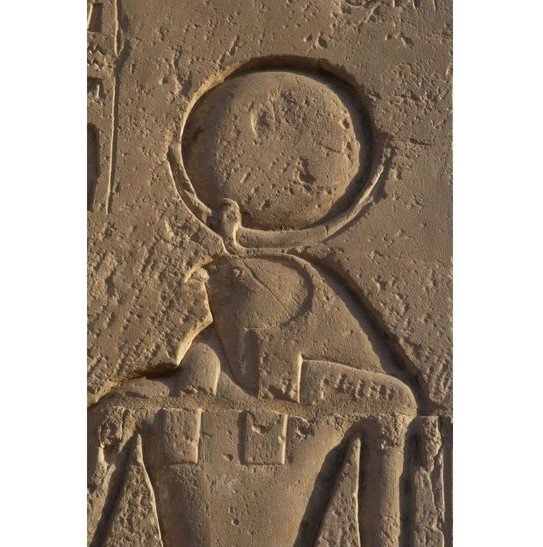

The ancient Egyptian deity Ra was depicted with a circle representing the sun (Credit: Alamy)

Investigating the function of the original circular halo in religious art only takes us back as far as the 1st Century BC. It had not featured in any prior religion, and yet it became a fixed piece of religious iconography across Eurasia within a few centuries.

It is likely to have evolved from very early art traditions. In ancient Egypt, the solar deity Ra was commonly shown with a circular disc representing the sun – although this was above his head rather than behind it. Meanwhile, some artefacts from the city of Mohenjo-daro (in the Indus valley), created in the 2000s BC, feature what look like rayed auras. However, these are inscribed around the whole bodies of holy figures, rather than just their heads. Likewise in the art of ancient Greece there are occasional representations of rayed crowns of light surrounding the heads of mythological heroes to suggest their unique divine powers. But the distinctive circular disc halo is an invention of a later date and presumably the result of unique religious ideas.

The earliest examples of a disc halo come from the 300s BC in the religious art of ancient Iran. It seems to have been conceived as a distinguishing feature of Mithra, deity of light in the Zoroastrian religion. It has been contested that the concept of divine glory (known as ‘Khvarenah’) in Zoroastrianism is intimately connected with the radiance of the sun, and that the halo was the pictorial means of relating this quality to Mithra, just as it had been for Ra.

In a matter of a few centuries, haloes had become Eurasia’s universal religious symbol of divinity

In terms of art history, the sheer speed at which the disc halo migrated across cultures makes it particularly noteworthy as a piece of religious iconography. By the 100s AD – just over a couple of hundred years after its creation – it could be seen in such far-flung locations as the Tunisian town of El Djem, the Turkish city of Samosata and the Pakistani city of Sahri-Bahlol. By the 400s, haloes had been embedded in Christian art in Rome and Buddhist art in China. Somehow, in a matter of a few centuries, they had become Eurasia’s universal religious symbol of divinity.

Buddha is shown with a halo in images around the world, such as in this Cambodian temple fresco (Credit: Alamy)

So how did the halo’s influence spread across the world and between religions? The initial movement of this piece of religious iconography is outwards east and west from its birthplace in Iran, in the hands of some of the past’s most powerful empires.

In the First Century AD, the Indo-Scythians (nomads from Iran) and the Kushans (from Bactria, Afghanistan) invaded the regions to their southeast, the territories now covered by modern-day Pakistan, Afghanistan and northern India. Both empires, which were steeped in ancient Iranian cultural history, brought coinage with them that represented Mithra with a halo. This youthful and attractive god with his divine radiance had an obvious appeal to a growing number of people around the Hindu Kush. So much so that the iconography of Buddha – even from the earliest visual representations of him, such as the Bimaran reliquary (which might date from the late First Century AD), show him with a Mithraic halo.

Meanwhile Mithra was also winning the hearts of the invading Roman Empire to the west – to the extent that Mithraism evolved into a major Roman religion. Mithras later influenced the iconography of another Roman deity – Sol Invictus (the “sun unconquered”). Both gods combined graceful masculine physiques with divine powers, linked to the sun’s radiance and authority, and so were worshipped by the most powerful members of society, especially the Roman Emperors. Constantine (Emperor 306-337CE) recognised the iconographical power of the halo, so he and his successors arrogantly appropriated it and used it in artistic representations of themselves.

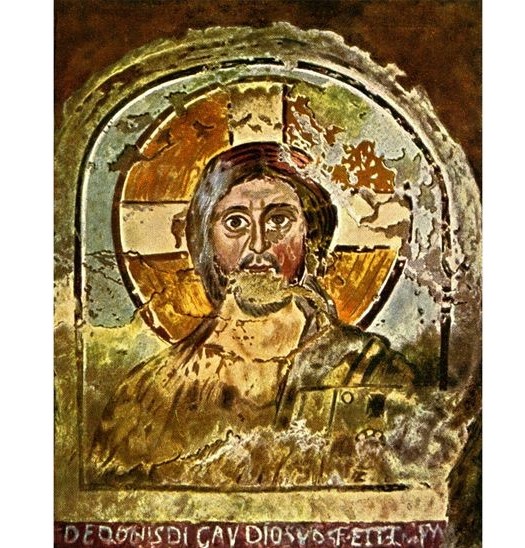

Jesus is sometimes shown with a cruciform halo, as in this early Christian fresco in the Ponzianus catacomb, Rome (Credit: Alamy)

Then, with the growing acceptance of Christianity in the Roman Empire, artists began to represent Jesus with a halo, now regarded as the highest symbol of divinely sanctioned authority. This new arrival in Christian iconography occurred from around the 300s AD, more than two centuries after it had appeared in Buddhism. It was a signal of Christianity’s metamorphosis from a marginalised religion to an official power structure in the west.

The halo has stuck in Christian art ever since, although it has undergone some adaptation over the years. God the Father can sometimes be seen crowned with a triangular halo, Jesus a cross-shaped halo and living saints a square halo.

Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism peacefully coexisted in India in the first millennium AD, and the three religions shared ideas and artistic iconography, including haloes. The earliest sculpted representations of haloes in Indian religious art come from the two great centres of art production, Gandhara (on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan) and Mathura (90 miles south of Delhi).

Trading in ideas

In late antiquity and the Middle Ages, Gandhara stood at the centre of an immense network of trading routes that stretched to China in the east and the Mediterranean in the west. Buddhist monasteries appeared along the key junctures of the trade highways to serve as religious versions of caravanserais. They offered a place for merchants to rest, pray and recuperate, and became the springboards from which Buddhism spread overland to China, where artists replicated the religion’s iconography. By the 500s AD, haloes were appearing in art in Korea and Japan, indicating the arrival of Buddhism in these regions too.

The same dissemination occurred for Hinduism which spread across Asia via overland and maritime trade paths, bringing religious attitudes and artistic styles to Indonesia, Malaysia and other South East Asian territories.

These wide-spread arteries of trade, which linked east to west in late antiquity and the Middle Ages, are often referred to as the “Silk Roads”, after the luxury goods shipped along them. But alongside exotic merchandise, these routes also transported religions, knowledge and iconography. The disc halo is an icon of this dynamic interchange of ideas that existed in the distant past. It started life as a Zoroastrian sign of solar divinity but was spread across Eurasia by ancient empires and trade networks that connected the edges of the known world. In the 21st Century, it is also a powerful reminder of humanity’s shared cultural heritage.