THE PROPRIETARY PLANTER -AN EXTINCT-by Hugh Karunanayake

Source:Island

The colonial history of Sri Lanka is characterised by the partial control of the country by the Portuguese and the Dutch, and complete control by the British. In the broader context of the colonisation of the South of the globe by the North, Sri Lanka together with British India were “transient” colonies as compared to the “settler” colonies of Africa, Australia, and the Americas.

While the Portuguese and the Dutch were interested in the cinnamon that grew naturally in the island, they did not have access or control of the mid or high country of the island which were controlled and came under the suzerainty of the Sinhalese kings. Furthermore, the vast expanse of the country’s hinterland excepting the ‘dry zone’ was under thick forest cover.

No attempt was made by either the Portuguese or the Dutch to engage in systematic cultivation of cinnamon despite cinnamon from Sri Lanka being acclaimed as the best in the world.

Ownership of land for commercial cultivation was a concept largely introduced by the British . The opening up of the country through a network of roads and railways provided access to areas thickly forested which soon fell to the axe. Crown land offered at between one tofive5 shillings per acre attracted many investors not unlike the Gold Rush in Calfornia.

According to the Ceylon Plantation Association records, in 1890, the bulk of the country’s tea plantations were centred around Dimbula, Dickoya, Maskeliya, Kelani Valley, Dolosbage, Pussellelawa, and Matale districts. By 1892 there were 11 tea estates over 1.000 acres in extent each.

A good proportion of investors were retired military men who had served in the East and thus were familiar with the climate and its potential. In 1837, some 3,661 acres were sold, and within nine years a total of 294,526 acres of crown land were sold mainly to Europeans. These sales created a new class of estate owners.

By 1913 there were sufficient absentee proprietors who managed their estates through agents who in June 1913 formed the Estate Agents Asoociation with with Mr Gordon Bois as Chairman. By April 1921 estate proprietors banded themselves together, and together with Estate Agents formed the Ceylon Estates Proprietary Association. Meanwhile, the nascent Ceylon Planters Asociation was gestating into a body representing the working planter, and by 1854 the Ceylon Planters Association was formed.

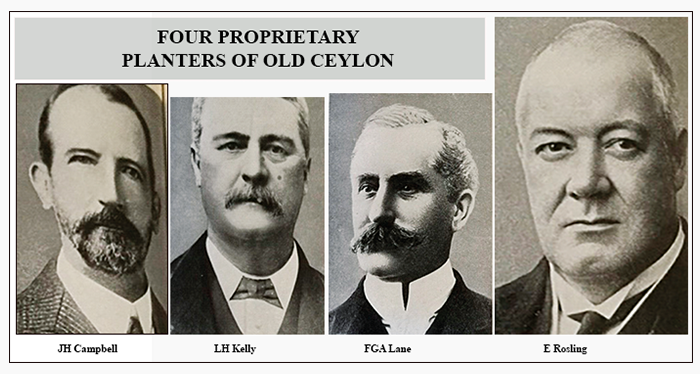

The concept of a person owning “broad acres” in Ceylon was a product of the first half of the 19th century. The photos below are of four proprietary planters. Top FGA Lane, E Rosling. Bottom LH Kelly, JH Campbell.

While the vast majority of estate owners were Britishers, there were wealthy Sinhalese and Tamils who having accumulated capital in trading enterprises sought to establish themselves in the “country squire” mode by investing in already cleared and planted tea and rubber properties. Indigenous entrepreneurs had in the meanwhile consolidated their planting interests in coconut properties which soon came under management models created by the British.

Some notable areas of capital formation for indigenous entrepreneurs were the arrack renting enterprises and the monopolistic rights to passenger transport both of which were almost entirely the domain of local entrepreneurs. They too ploughed their accumulated reserves into plantation enterprises.

These capital formation trends were exacerbated by the post independence departure of British proprietary interests which accelerated the growth of a local plantation owner class. In fact the Ceylon Estates Proprietary Association was formally dissolved in May 1947, three months after the granting of independence to the country.

Investment in other real estate such as in house and property also accelerated during the first half of the 20th century. The resulting social inequities led to legislative enactments aimed at levelling social and economic disparities. The Ceiling on Housing Act and the Land Reform Act have effectively stymied the polarisation, but with some detriment to overall economic growth. Consequently, the proprietary planter from the plantation sector and the landed proprietor from the urban scene have both seemed to have not only lost significance but seem to have disappeared totally.